Fantasia Film Festival Reviews: ‘The Deer King,’ ‘Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko,’ ‘Pompo: The Cinéphile’

Montreal’s Fantasia International Film Festival is halfway through its three-week virtual edition, and we’ve managed to catch some of the most exciting and intriguing films in its program.

Historically, the festival has had a strong connection with anime, and this year’s edition is no exception. We’ve watched three of its Japanese features: The Deer King, Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko, and Pompo: The Cinéphile. Read on for our reviews (and click here for our thoughts on the anime documentary Satoshi Kon, The Illusionist, which is also playing at the festival).

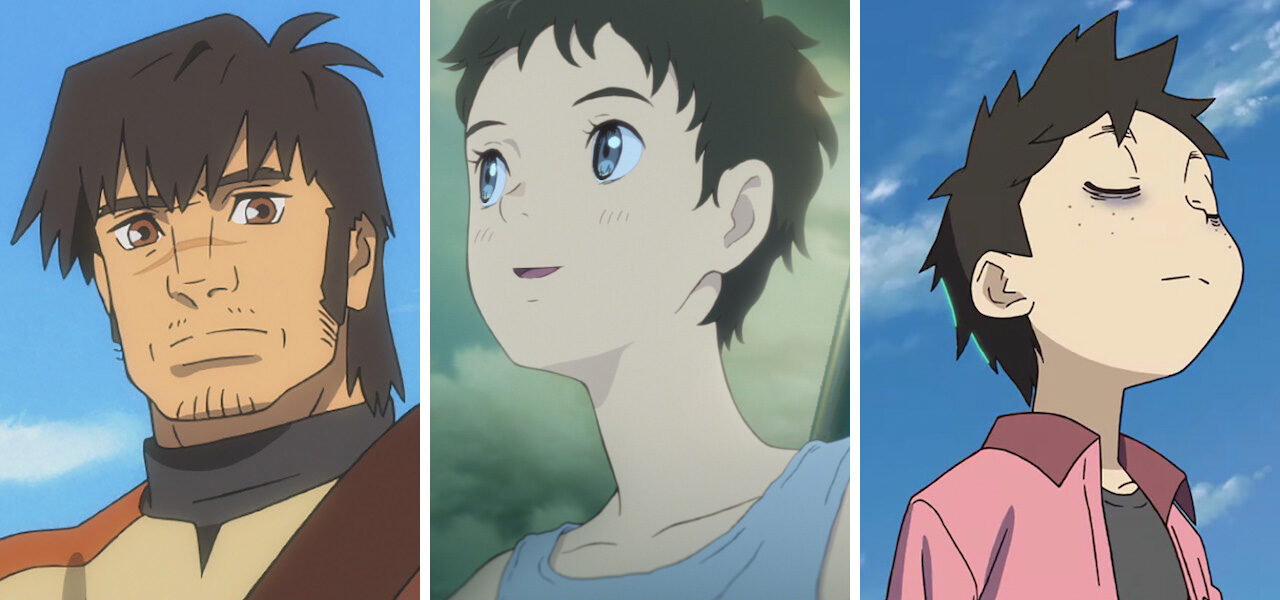

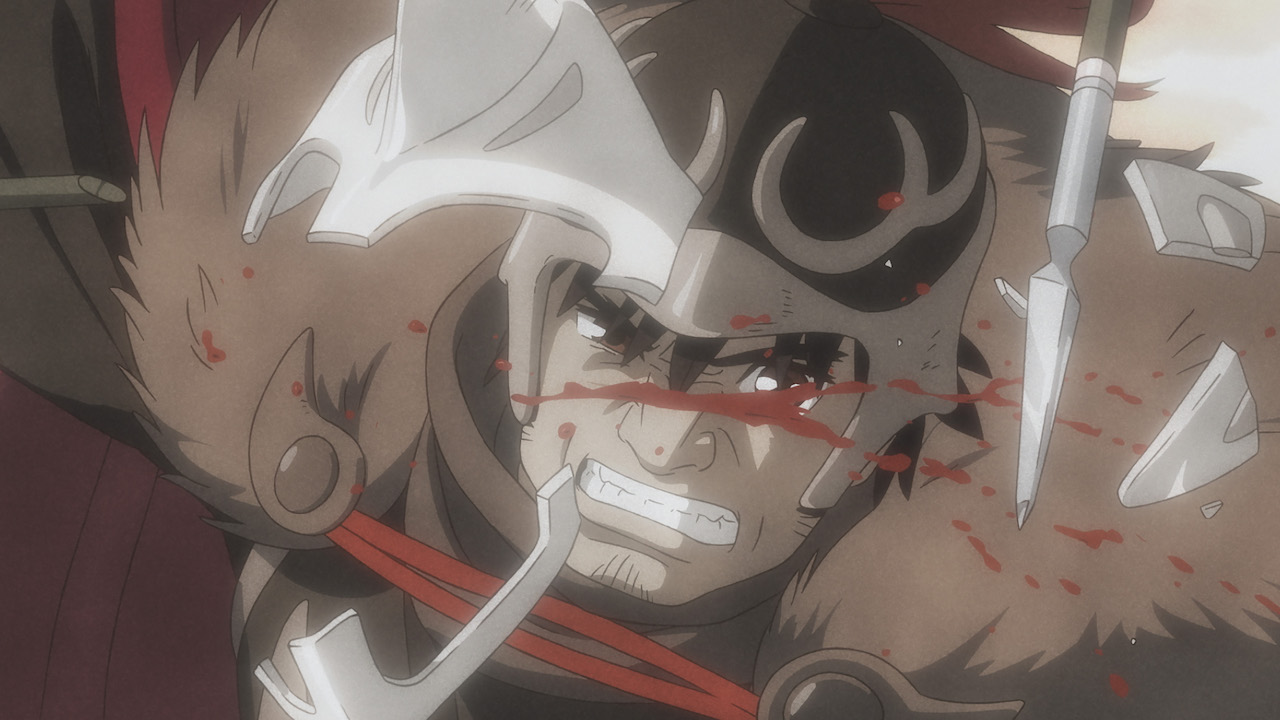

The Deer King

The debut feature from Masashi Ando, known for his character design and animation work with Studio Ghibli and Satoshi Kon, and the second from his fellow director Masayuki Miyaji (Fusé: Memoirs of the Hunter Girl), The Deer King is a transportive clash of the old and new from its opening moments.

The film adapts the novel series of the same name by Nahoko Uehashi. A mighty amount of exposition is crammed into its first five minutes, but the story is familiar: a group of warriors called The Lone Antlers fought back against an invasion of their country by the Empire of Zol, and lost. Their leader and captain Van is imprisoned, but escapes with a young girl named Yuna after a mysterious attack from supernatural wolves (expect plenty of Princess Mononoke comparisons, not unearned).

From here The Deer King’s focus is constantly shifting, in a manner that feels right for its patiently paced and observant odyssey. Though the traveling companions change, Van remains the anchor, gradually opening up as his relationship with his new adoptive daughter changes him.

That, and his newfound spiritual connection to the natural world, dovetail with the film’s fantasy and sociopolitical context in surprising ways. A number of old stories — the found family, nature pushing back against human industry and empire — are told here with new verve. The film feels pleasantly traditional, but distinguishes itself with an atypical approach to fantasy: billed as a “medical fantasy,” it looks to scientifically rationalize its various mysteries.

As expected from the impressive creative talent involved, The Deer King is lushly presented, full of gorgeous lighting and background art, its beautiful character drawings carrying the visual signatures of Ando’s work with both Ghibli and Kon in their attention to the little quirks and imperfections of their faces. (Ando serves here also as animation director and character designer.)

Ando and Miyaji’s professional background can also be seen in the complex and well-considered lore of the decaying kingdom, as well as how the characters move with an incredibly believable weight, no matter how surreal or abstract the imagery surrounding them becomes in the later acts.

The Deer King emphasizes its strong connection with the earth through the real human heft of its animation, a strong balance to the film’s frequent spiritual and out-of-body experiences. That attention to every nuance of movement of its humans and animals, the consideration of the strain of muscles or the smallest twitches in the face, reflects the film’s grounded and humanist approach to its large-scale fantasy.

It’s a helpful anchor because the narrative is incredibly dense. But aside from its sweeping opening it rarely feels overwhelming, as it carefully unspools the complications born from the offscreen conflict: political change, social unrest, love between people from warring nations, the belief in divine retribution. The Deer King is truly engrossing and rich in its world building, but it leaves enough unsaid that viewers will walk away wanting even more.

GKIDS will release “The Deer King” theatrically in North America early next year.

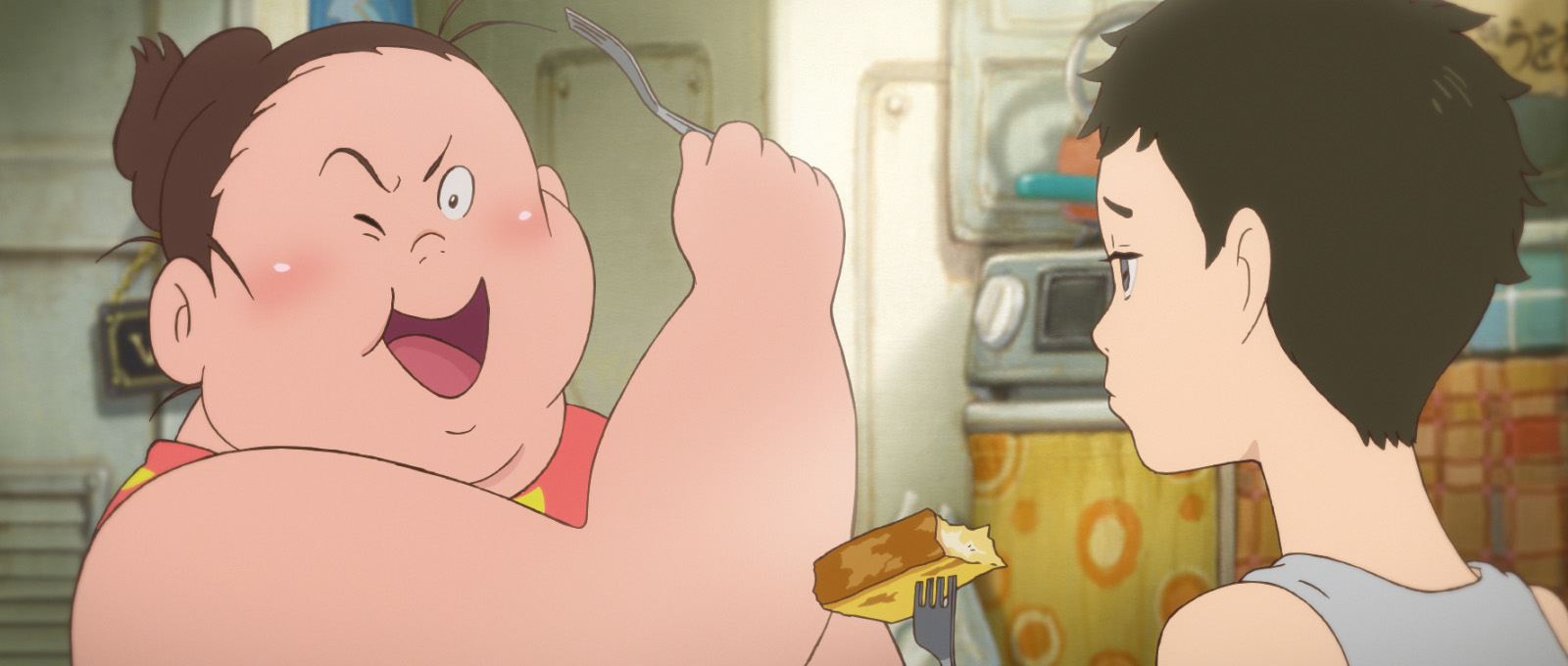

Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko

After the sprawling and mesmeric abstract fantasy of Children of the Sea, director Ayumu Watanabe comes back to an earthly plane with the humble Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko. Where his previous film worked in a lot of plot and existential questions, Nikuko is considerably sparser and smaller-scale.

Based on the 2011 novel of the same name by Kanako Nishi, the film centers on Nikuko and her 11-year-old daughter Kikuko, who live in a houseboat in a small seaside fishing town to which they have only just moved. Nikuko has a tendency to fall for men who let her down, and each heartbreak takes the pair to a new place.

Despite the film being named after Nikuko, Kikuko is the real focus. Watanabe examines her inner life and little schoolyard dramas, treating them seriously no matter how trivial they seem. The film overtly recalls iconic imagery from My Neighbor Totoro, and also shares its willingness to treat a child’s perspective seriously and with great care.

By comparison, her mother Nikuko, who works as a waitress in a local bar, is treated like a cartoon, a sort of foil for Kikuko. Her larger-than-life attitude naturally embarrasses the still-young Kikuko, but the film pushes too far in seeking to mine comedy from Nikuko, too often looking for cheap laughs at her weight. This feels egregious in a film that treats its other main character with such subtle and sensitive care.

The film’s saving grace, then, is that it mostly remains with Kikuko, enlivening her point of view through its lovely craft. Kenichi Konishi’s character designs range from a subdued realism and scratchy lines in the weathered faces of kindly old-timers to the exuberance of wide-eyed, gangly teens.

Despite the vast difference in tone, the film is something of a reflection of Children of the Sea: both are coming-of-age stories about girls attuned to the voices of the world around them. So, appropriately, just as the natural world in Children of the Sea held a voice of its own, so it does here, partly through the lively, complex detail of Shinji Kimura’s art direction.

As he did in Children of the Sea, Kimura designs the world around Kikuko to complement how she perceives it, with plants and animals conversing with her and each other. That rich liveliness is realized with lovely compositing, which highlights earthy textures and gentle, natural interplay of light and shadow.

Bolstered by that visual acuity, Nikuko is a mostly pleasant, low-stakes series of vignettes that occasionally undermines itself, but mostly charms with its easygoing coming-of-age narrative.

Pompo: The Cinéphile

Pompo: The Cinéphile starts with an absurd pitch — a mercenary, no-nonsense child-prodigy producer is renowned for making gleefully trashy B-movies — and only gets sillier from there. But the focus of Takayuki Hirao’s film is not so much on the eponymous character as it is on her production assistant Gene.

After having Gene run a number of menial tasks, Pompo sees fit to assign him as the director of her passion project. It’s a script that she wrote for a more prestigious movie, the kind of classical blockbuster destined for awards season (Pompo’s industry, Nyallywood, is a thinly veiled simulacrum of Hollywood). The rest of the film follows Gene through pre-production, shooting, and post-production as he learns how to be a director on the fly.

Pompo is more ridiculous for its naive earnestness than for any kind of knowing or satirical silliness. For starters, it portrays Hollywood nepotism as a good, uncomplicated thing rather than a symptom of a narcissistic industry. Hirao, who also wrote the script (adapting a manga series by Shogo Sugitani), threads the needle from this, to the making of a big-budget Oscar-bait picture, to syrupy sentimental monologues from those beloved champions of creativity, bankers. That part is so bizarre that it almost comes back around to being entertaining.

The film is certainly passionate about filmmaking, and deserves props for efforts to conjure up excitement for the less glamorous minutiae of the craft. A lot of the film’s most audacious visuals are reserved for the edit suite: there’s a hilarious, charmingly heightened representation of how it feels to press a delete key, in which Gene holds a big sword and slashes at giant flying reels of film.

Aesthetically and otherwise, Pompo represents all of Hollywood’s allure with few of its complications: it’s shiny, pretty, and also shallow. Its earnestness doesn’t feel inherently wrong in itself — in fact, that idealism is quite pleasant. But it carries a nagging feeling of falsity.

It’s no Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken!, the recent Masaaki Yuasa-directed series about storytelling in the medium of animation, which was also (intentionally) outlandish but showed a lot more nuance in its engagement with the difficulties of such work, as well as more visual imagination. It’s perhaps an unfair comparison — but when such a series exists, it’s hard not to see Pompo’s scope as narrow.

There’s enough pleasantness in Hirao’s visual style to keep it from being unwatchable, but Pompo’s charming enthusiasm can’t compensate for its frequently trite vision of its chosen profession.

Fantasia runs until August 25, with online screenings geo-locked for Canadian viewers.

.png)