‘Claydream’ Review: Will Vinton Doc Exposes Viciousness Of Legal Battle With Phil Knight

Before his death in late 2018, animation legend Will Vinton hadn’t worked in the medium for over a decade. The end of his storied career, which had seen him popularize claymation, came when he was ousted from the company he created, Will Vinton Studios.

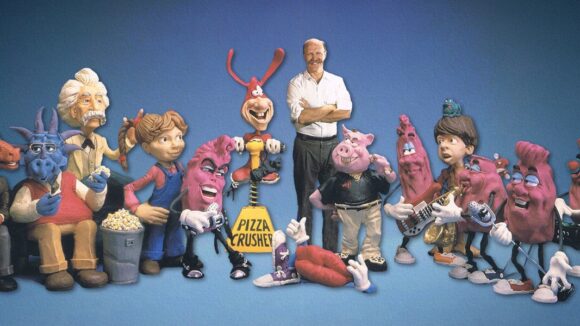

In the new documentary Claydream, director Marq Evans molds plenty of raw material into a loving portrait of Vinton’s genius. Less flatteringly, he also reveals the artist’s self-aggrandizing side. Finally, he crafts a damning account of how Travis Knight, through his father (and Nike co-founder) Phil Knight’s financial prowess, took over the studio and built the renowned stop-motion house Laika on the ragged corpse of what Vinton had created.

In 1998, when Vinton’s studio was rather prolific, Phil Knight saw it as a profitable investment. Soon after, Travis was given a job as an animator at the studio. As the studio’s position became more precarious, Vinton asked Phil to invest further capital. Unbeknown to Vinton, Phil bought out other shareholders and became the majority shareholder and director of the studio, then introduced a clause into Vinton’s contract that made it legal for him to be removed without cause.

Video of the legal depositions in the ensuing Knight v. Vinton case, which implies the removal of the founder was premeditated, serves as the film’s framing device. As Evans lays out Vinton’s pioneering history and the series of decisions that had weakened the studio by the late 1990s, he also calls into question the Knights’ actions. Father and son come off as villainous and their predatory approach appears beyond opportunism, even when taking into account Vinton’s costly missteps.

Formally Claydream doesn’t propose anything ingenious, but it does feature extensive clips of Vinton’s work and — more importantly — in-depth discussion of its themes. We see how Vinton, who seemed unable to engage directly with his negative emotions, may have funneled them into his work, and how his artistic sophistication sometimes prevented him from achieving wider success.

Evans, who started working on this project prior to Vinton’s passing, has exclusive interviews with him. He also speaks to many of Vinton’s collaborators and other personalities within the industry, such as Bill Plympton, Craig Bartlett, and animation historian and former Cartoon Brew editor Jerry Beck.

Through their accounts the director shapes a timeline beginning with Vinton’s early collaborations with Bob Gardiner, which yielded the Academy Award-winning short Closed Mondays, but also haunted Vinton for many years after. Gardiner’s mental health issues and substance abuse drove him to a vindictive, years-long spree of attacks against his onetime partner.

In the only animated feature he directed, The Adventures of Mark Twain, Vinton fell prey to the public’s persistently narrow view of animation. Intended for a mature audience but sold as a children’s production, it failed. Economic prosperity came — at the cost of creative renewal — when the studio devoted its artists to projects involving the now emblematic California Raisins, and commercials involving characters like the now-famous talking M&Ms.

A paragon of the creative entrepreneur, Vinton was a self-taught animator who experimented, pushed the medium, and charted his own course — like Jim Henson did with puppets or Pixar with computer animation. Yet he was also desperate to be perceived as the successor to Walt Disney, a complex that clouded his judgement. In that pursuit he tried to fabricate characters that would lead to a marketable empire with a theme park to boot.

Personal flaws notwithstanding, Vinton made inspired choices rarely seen, even today, in the animation industry, such as hiring every one of his more than 300 employees full-time with health benefits. It was perhaps not seen as a sound business move, but it gave people stability.

Footage of the legal battle exhibits the disdain the Knights had for Vinton. They were, Vinton believed, bent on taking the studio from him so that Travis, whose career as a white rapper hadn’t panned out, could have something to put his time into. Knight Senior comes across as an unscrupulous shark. When Vinton was fired, they gave him an offensively low $50,000 as severance for a lifetime of work. The documentary’s talking heads argue that the pair intended to demoralize and humiliate the artist. They haven’t faced enough public scrutiny over this transaction.

Vinton’s studio was reopened as Laika, whose artists, president and CEO Travis included, have proven their immense talent over the years. But as Evans tells it, the way the Knights acquired the studio seems vile. In his final days, Vinton showed grace by not denouncing the Knights but instead praising their advancement of stop-motion animation. Though Evans tries to end his film on a sweet note by showing this, the bad aftertaste from the details of his demise is hard to shake.

“Claydream” premiered at the Annecy Int’l Animation Film Festival. We reviewed the film out of the Tribeca Film Festival, where it also screened last week. No U.S. release has been announced.

Director: Marq Evans

Producers: Tamir Ardon, Marq Evans, Nick Spicer, Kevin Moyer

Screenwriter: Marq Evans

Cinematographer: Jason Roark

Composer: Heather McIntosh

Editors: Lucas Celler, Yakima

Executive producers: Nate Bolotin, Aram Tertzakian, Duke Johnson, James A. Fino, Dan Greeney, Kathryn M. Moseley

Associate producer: Wesley Cannon, John Larson, Michael Noland, Michelle Quisenberry

Co-producer: Kevin Noland

Story by: Marq Evans, Tamir Ardon

Music supervisor: Kevin Moyer

Cast: Will Vinton, Bill Plympton, Bob Gardiner, Melissa Mitchell, Chuck Duke, Craig Bartlett

.png)