‘Mouse in Transition’: The CalArts Brigade Arrives (Chapter 9)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition will be published every Friday on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Read Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Read Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Read Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Read Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Read Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

Read Chapter 6: Detour into Disney History

Read Chapter 7: When Everyone Left Disney

Read Chapter 8: Mickey Rooney, Pearl Bailey and Kurt Russell

“Chief has to DIE,” Ron Clements said. “The picture doesn’t work if he just breaks his LEG. Copper doesn’t have enough motivation to hate the fox.”

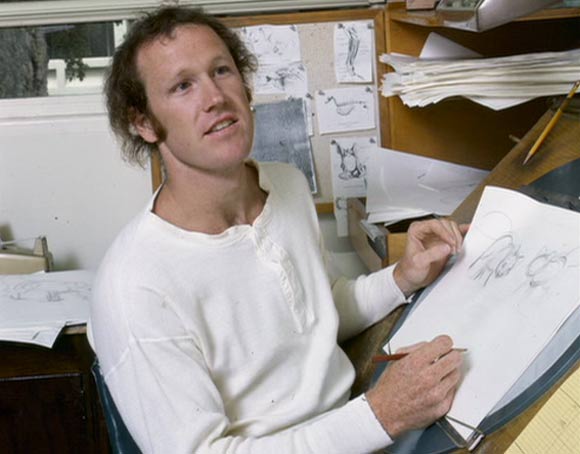

Ron looked at me intently, shaking his head. He was a supervising animator on The Fox and the Hound, and was just then in the process of making a jump into the story department. He was something of a perfectionist and (for some reason) wanted the story to be better.

Ron had worked for a season at Hanna-Barbera and then entered the Disney training program, apprenticing with veteran animator Frank Thomas. Within a decade he would be co-directing Disney’s breakout blockbuster The Little Mermaid, but at this moment he was unhappy with the story arc of The Fox and the Hound.

“I agree with you, Ron,” I said. “Agree completely. But do you think Art Stevens will buy a change like that?”

“I don’t know. But we have to try. The picture needs to be stronger.”

The Fox and the Hound had a three-act structure. The second act had the fox, Tod, involved with a railroad accident. The old dog Chief gets knocked off a tall bridge by a thundering locomotive, and Tod gets unfairly blamed for the accident. Chief dies in the book on which the movie is based, but in the Disney version, the elderly dog only suffers a broken leg. Even so, Copper (the young bloodhound) angrily vows revenge against his friend Tod.

Ron and most of the younger story crew thought Copper’s anger and lust for revenge was several clicks over the top, considering Tod’s minor sin. So Ron and the rest of us pleaded the case to the lead director: “Please let’s have Chief DIE.”

Art was skittish about it, and said no. No surprise there. So the same argument was hauled upstairs to Disney’s management, with the same reaction:

“You can’t kill off a lovable central character! Children will FREAK OUT! Parents will hate us! WE’LL GET LETTERS!!”

Neither tearful pleas nor the example of Bambi’s mother catching a bullet could change the directors’ or the top brass’s minds. They wouldn’t kill Chief, and that was final. Ron Clements was not a guy who easily took “No” for an answer, but after a protracted campaign, he dropped the issue. Arguing was as pointless as jousting with windmills. (I had dropped the issue earlier. I am not a big believer in banging my head against hard, thick walls.)

But it was one more point of dissatisfaction between the recently-arrived Young Turks and the Disney Animation establishment. The old timers from the 1930s were gone, but the generation that had rolled in during the 1940s and 1950s was finally holding the tiller, and they were bound and determined not to cede their newly acquired power and leverage to a bunch of goddamn kids in their goddamn twenties.

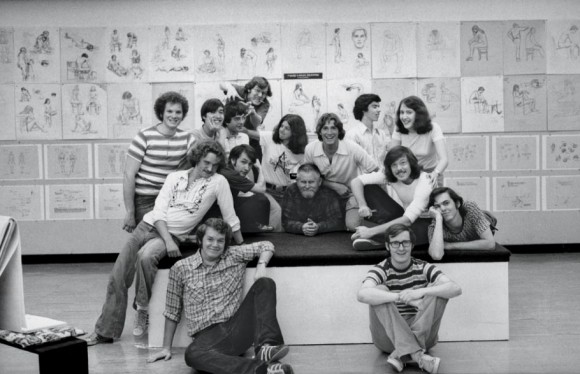

Many of the “kids” were from California Institute of the Arts, the Disney-funded college in Valencia, California that served as a training ground for a lot of the animation industry. Walt Disney Productions had, in recent years, skimmed off the cream of the CalArts crop, and recent grads like John Musker, Henry Selick, Brian McEntee, Bruce Morris, Joe Ranft, Mikes Cedeno, Mike Giamo, Tim Burton, Jerry Rees, and an ebullient CalArts star named John Lasseter (among numerous others) populated the animation building.

A 1980 volleyball game between the Disney producers and artists. The color commentary and play-by-play by John Musker reveals the underlying tensions between the two camps. Video by Randy Cartwright.

Most of the CalArts group groused about the old-timers’ stodgy, moldy fig attitudes, and the stodgy, moldy fig product that resulted therefrom. They had been against the Bluth forces; now they chafed against the veterans’ tightly-held reins. Brad Bird had already gotten his ass fired for making his gripes too loud and too public, but the general mood of frustration and desire to try something fresh, new, and different continued.

Even with the bad feelings, various CalArts graduates were being groomed for better things. Early on, John Musker jumped on a career track pointed toward director. John Lasseter was assigned to different projects in development. Bruce Morris and Joe Ranft quickly worked their way into story development.

But the veterans remained territorial…and a touch paranoid. I remember Art Stevens saying, “Who do these pipsqueaks think they ARE?! They’re not geniuses. They can’t come in here and have their way after fifteen minutes!” (Another old-timer told me: “Art spent years in John Lounsbery’s unit as his key assistant. And Art would get furious if artists in their group tried to move up and out. He always wanted everybody to stay where they were, to not change anything. He’d get offended if anybody tried to jump ship.”)

Tim Burton, bent over a light board down on the first floor, was becoming known for his very un-Disney character sketches. Joe Ranft, Darrell van Citters, Brian McEntee, Mike Giamo, Jim Mitchell, and Sue Mantel de Sico were staging elaborate holiday puppet shows that featured big cardboard cutouts of Doris Day and Eddie Fisher—and dummies thrown off the Animation Building’s roof. Crowds would gather to watch the productions.

Many of these side endeavors came about because they were another way for newbies to showcase their creative chops, and also have a good time. Few of the new employees were excited by The Fox and the Hound. None were happy with the stone-walling of Disney Animation’s middle management.

“All we had to work on was an old-fashioned animal picture that was kind of a cross between Bambi and Lady and the Tramp, only not as good as either of those,” one of the CalArts employees told me later. “And all we had to look forward to was a sword and sorcery feature [The Black Cauldron] that nobody thought was going to be much better.”

Regardless of the younger employees’ attitudes, The Fox and the Hound was moving (make that “limping”) into the final lap of production. The feature had a solid opening and satisfactory Act I, a so-so Act II (Chief still needed to get killed instead of crippled, and Tod’s first night alone in the forest was underwhelming), and a pretty good Act III that featured a nasty fight with a grizzly bear.

CalArts alumni Glen Keane and Jerry Rees thought they could amp up the climactic scenes with the bear, and re-boarded the grizzly fight from start to finish. They gave it more dynamic staging and turned it into a savage battle. The sequence’s director, seeing his territory being invaded, pulled it back a bit, but the final result was more powerful and emotionally involving, strengthening the picture.

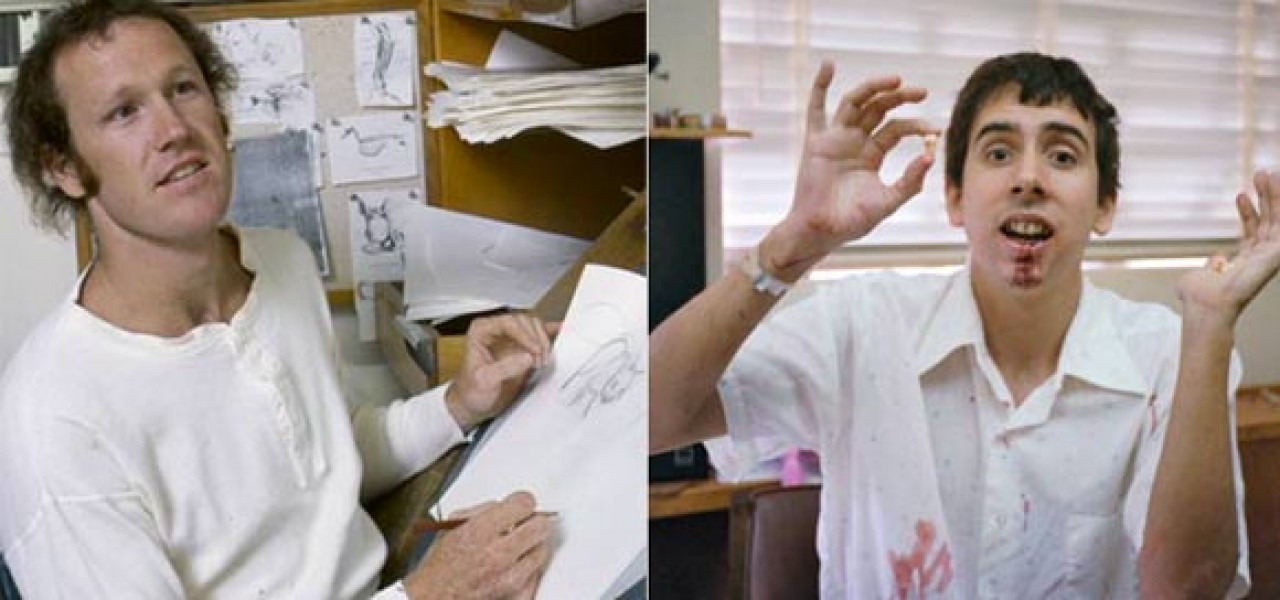

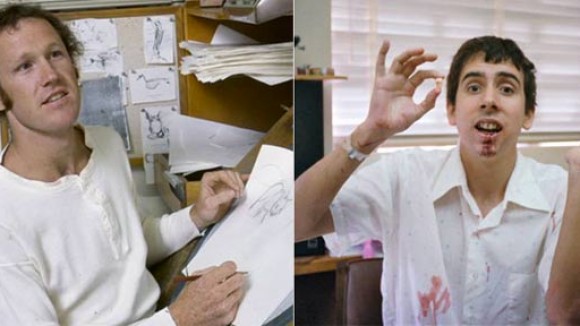

While the studio prepped the new feature for release, Disney’s publicity department sprang into action. The head of the department thought it would be a good idea to promote the film with a college tour of a documentary showing younger staff talking about their experiences on the picture. The youngsters turned out to be an animator/story artist named Tad Stones (later a producer and showrunner for Disney Television Animation), me, and a second young animator: Tim Burton.

We all sat on stools responding to questions as the camera rolled. Tad was crisp and articulate, I stumbled through half of my answers, and Tim stared, blinked, stammered, and upstaged everybody through the length of the film. Every time I said something halfway dumb (which was often), Tim leaned forward and gaped at me. And every time Tim was thrown a question, he would put topspin on it. When he was asked how he came to be hired by Disney Animation, he responded, “I don’t know. I was walking down the street one day and they dragged me in here.”

Hulett, sadly, was neither glib nor quirky. After one question, I hesitated for a couple of seconds, mustering my thoughts. When the film editor and publicists saw it on film, they decided it would be amusing to dub in a loud, Goofy-like swallow in the middle of the pregnant pause.

Which they did.

I was told this part of the film got big laughs on the college circuit, but I never saw the final product. After a young publicist told me how hysterically funny Tim was…and how klutzy I was, I decided to pass on a private screening. The closest I came to viewing the documentary was when I heard my voice coming out of a third-floor sweat box one day, along with muffled laughter. Realizing what film was being viewed, I turned on my heel and walked the other way. Fast.

The Fox and the Hound was finally released in July of 1981, a year later than it should have been, with a final budget of twelve million dollars. (You’ll recall that Wolfgang Reitherman complained that The Rescuers had cost seven-and-a-half million dollars. What a difference five years makes.)

The crew wrap party was held on the town square set of the Disney studio’s back lot, designed as a country fair. There were food booths and game booths, corn on the cob, and barbequed ribs. There were big rectangular tables with checkered tablecloths and folding chairs. (Obviously no expense had been spared.)

Somebody said that the teenaged John F. Kennedy Jr. was in attendance, but I neither met him nor saw him. My brush with celebrity came when I toted my plate of grub to one of the rectangular tables and found myself sitting across from eighty-year-old Rudy Vallée, who looked like Methuselah’s slightly younger brother. I tried to make small talk and pretty much failed.

The studio showed the finished film in the big theater right before the crew party. I sat through half of it. When you see story reels for an animated feature month in and month out, you get tired of them. You also lose judgment about what’s good, what’s bad, and what needs to be done over.

I was still in that “I’ve seen it ENOUGH!” state. I sat in the dark listening to lines I had written two and three years before, and it was like somebody else had written them. In a sense, somebody else had, because I was not the same nerd I had been in 1978 and 1979. I was now a Disney feature animation nerd, with the production scars to prove it.

In 1981, Disney Feature Animation was still part of a sleepy Hollywood backwater named Walt Disney Productions, but most of the old guard was now gone or on its way out the door, and the river channel was shifting. I wanted to be out in midstream when the new tide came in, but wasn’t convinced I was a strong enough swimmer to survive.

I would soon find out.