‘Mouse in Transition’: Rodent Detectives and Studio Strikes (Chapter 11)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition will be published every Friday on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Read Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Read Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Read Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Read Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Read Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

Read Chapter 6: Detour into Disney History

Read Chapter 7: When Everyone Left Disney

Read Chapter 8: Mickey Rooney, Pearl Bailey and Kurt Russell

Read Chapter 9: The CalArts Brigade Arrives

Read Chapter 10: Cauldron of Confusion

Basil of Baker Street by novelist Eve Titus was an illustrated children’s book centered on a mouse who fancied himself an ace detective. The mouse resided (naturally enough) inside the walls of 31 Baker Street in London, home of a human-sized ace detective, the name of whom escapes me.

Animator and story artist Ron Clements had run across the novel before coming to Disney, and had pushed the idea of turning Ms. Titus’ book into an animated feature. Around the same time, Pete Young discovered the book and worked up a large color visual of Basil in action. He showed it to studio top-kick Ron Miller during a short meeting, and that quick presentation resulted in a green light to develop the book into a movie.

Which was fortuitous, because the younger contingent of The Black Cauldron’s story crew was at that moment being shoved out the door marked “Exit.” (Disney veteran Burny Mattinson avoided the Cauldron story wars by getting approval to develop and direct a Mickey Mouse featurette based on Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Smart man, Mr. Mattinson.)

John Musker, heretofore a Cauldron director without any Cauldron sequences to direct, transitioned to the same position on Basil… and so had a project to actually work on. Peter Young became de facto story supervisor.

I cobbled together a rough outline, taking various episodes and characters from the book which the studio had purchased at a bargain price. The novel was a thin 100-plus pages, and Pete was not enamored with the story, so we created a lot of new plot.

Early on, the questions were: How do we show the parallel rodent world visually? And how do we introduce and set up the characters? The opening sequence soon had a two-track approach: Director Musker explored character development and gags; Pete Young pushed ahead with plot. Two sets of story boards came into existence, one focused on gags and Basil’s eccentric behavior, and one on story.

But before either version of Sequence One had progressed very far, outside events crashed in on our new story unit and brought Basil of Baker Street’s forward momentum to a creaking halt.

The union that represented Disney’s animation unit had been making noises about going out on strike. Three years before in 1979, union members had hit the bricks over cartoon work being shipped out of the country. The studios were taken by surprise and the union secured contract guarantees to keep more of the work stateside after a two-week strike. At the time, Walt Disney Productions hadn’t been involved because WDP had never sent work overseas.

By 1982 that had changed. And the Disney animation staff found itself sucked into Round Two of the fight to keep animation jobs in southern California.

I was a member of the Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists, Local 839 of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employes (there’s a mouthful), but what I knew about the union was minimal. I had joined the organization six-and-a-half years before, paid the initiation fee, paid the dues, and once in a while partook of the union health coverage (which was excellent.) But I had never been to a union meeting and had no idea where the union hall was located. And union rules? The union contract? They were dark mysteries wrapped in a fog bank.

But now, in the late spring of 1982, I was growing more engaged. Out of necessity. A special union meeting at the Lockheed Mechanics Hall took place on a balmy Tuesday night. Word was out that a strike vote would be held, so I drove up Buena Vista Street to participate in my first meeting.

The Mechanics Hall was the size of a thirty-lane bowling alley, and the three hundred fifty odd MPSC members who sat on folding chairs filled only a fraction of the hall. A crusty old layout artist named Mo Gollub, president of the union and a veteran of the 1941 Disney strike, stood up front chairing the meeting. He was weathered, wiry, and sported a gray goatee. Behind him stood union executive board members—none of whom I knew —and union business representative Harry “Bud” Hester. Bud I recognized. I had seen him in the Animation Building hallways back when he still worked at Disney.

The proceedings got off to a brisk start with Harry and Mo synopsizing the issues: The union had won protection for studio employees against job losses in 1979. The studios now wanted to take those protections away so they could lay off more workers. The Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists union needed a “Yes” vote regarding the strike to give it more clout at the bargaining table.

A motion was made for a strike vote, then there were questions from the floor. The first one was, “How long will a strike last?” Mr. Gollub said, “As long as it needs to, but the last one was short.”

A skinny board artist jumped up and said that this time the studios were ready for a strike, and that the union shouldn’t go out. Mo snapped, “Not true.” Then somebody wanted to know if the International (whatever that was) supported the union going on strike. “Yes. Absolutely,” Mo answered.

Finally a heavy-set woman with big hair and bigger glasses got out of her chair and asked if this was THE strike vote, or would there be another? Mr. Gollub said that no, this wasn’t the final vote. One more would happen before members walked out in a job action.

(This sounded weird to me, but I was an infant in the ways of labor strikes, and chalked up my confusion to ignorance. Only later did I find out from an executive board member that yeah, this WAS the only vote. Nobody ever explained why Gollub said what he did, and nobody corrected it.)

Discussion came to an end, and the vote was called. Two-thirds of the assembled multitude voted “yes,” one third “no,” and that was that. Business representative Hester stepped forward and thanked people for attending, reiterating that the vote would give the Screen Cartoonists the ammunition it needed to keep the language in the contract that would stop runaway production.

Such, it turned out, was not the case. Negotiations quickly slammed into an unyielding corporate wall. The companies with the anti-runaway language insisted it had to go. Walt Disney—until now the sole company without the clause—argued strenuously that the restrictive language would never get into ITS collective bargaining agreements.

The contract and prohibition to strike expired on July 31. And the Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists was standing on the edge of a tall cliff with a very long drop. Word was passed that a job action was imminent, and Disney animators, story artists, and assistants grew tense. What would a strike mean to people’s careers? How long would artists be pounding up and down the sidewalk lining Buena Vista street, toting picket signs? And what would everyone do for eating money if the strike dragged on for a long time?

Nobody knew. There hadn’t been an animation strike at Disney in forty-one years.

Day One of the prospective job action finally arrived, and the entire animation staff assembled in the studio theater. Business rep Hester stood at the front and explained why every employee needed to walk out. There had been a “Yes” vote for a strike, the union was fighting to retain contract guarantees against work going overseas, and Walt Disney Productions wouldn’t agree to the language. So members of the Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists needed to “go out” to give negotiators more leverage.

People raised their hands and asked questions. Was the union going to negotiate with Disney during the strike? (Yes.) Could anybody on strike collect unemployment? ( No.) Was there a way of getting money after Disney paychecks stopped? (The union would make some no-interest loans if it became necessary.)

The question-and-answer session went on for three-quarters of an hour. Hester was a touch nervous and ill at ease, but he responded to every query. Even so, the uneasiness of the audience didn’t go away.

Then a man in a blue blazer and expensive haircut stepped to the front of the room. I forget his name, but he was a human resources executive from Disney World, and he smiled and said he was there to answer any questions and concerns employees had.

Only mostly he didn’t. Mr. Haircut had an irritating way of dodging around questions, saying either he was not at liberty to respond or being non-committal with double-talk. He would have made an excellent used car salesman, but he was a lousy spokesman for Walt Disney Productions. By the time he finished, most of the animation staff were willing to walk out the main gate and hoist a picket sign due to the studio spokesperson’s general oiliness.

I still had mixed feelings about striking, but I decided to be a good foot soldier and exit the lot with everybody else, so it was down the narrow studio streets, into the parking lot, and out past the guard shack. People were already milling around the sidewalk fronting Buena Vista Street where Hester was talking to a couple of TV news reporters with their camera crews.

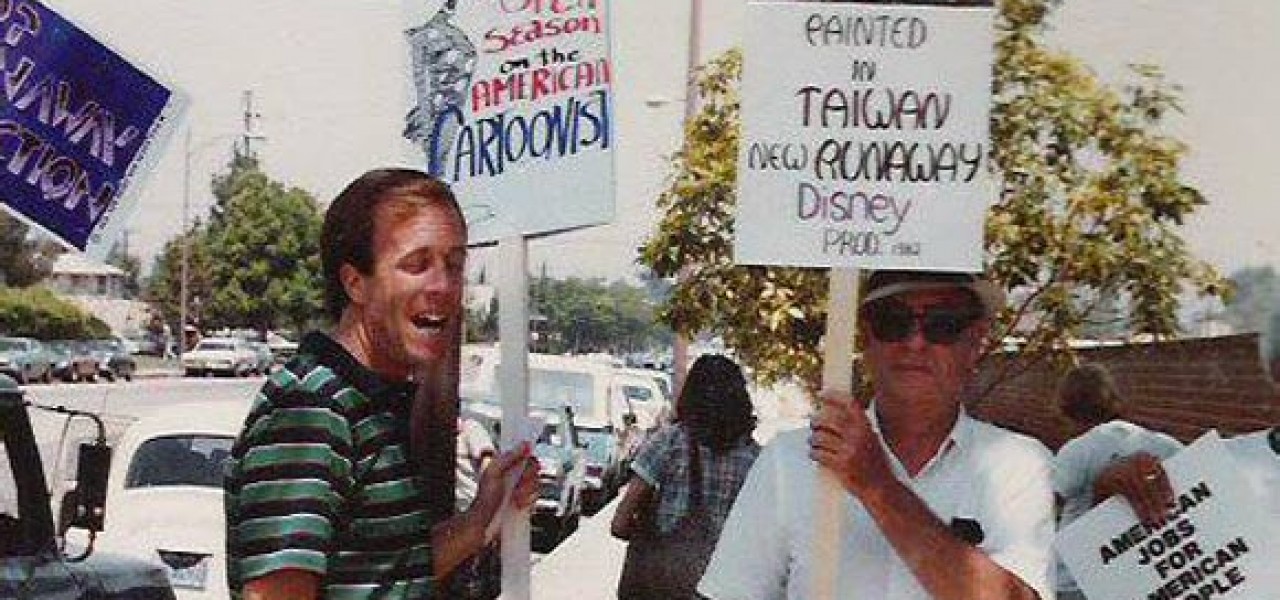

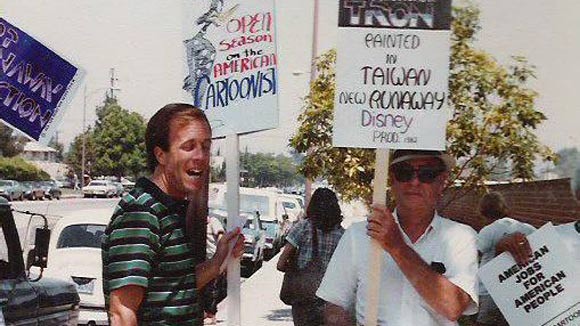

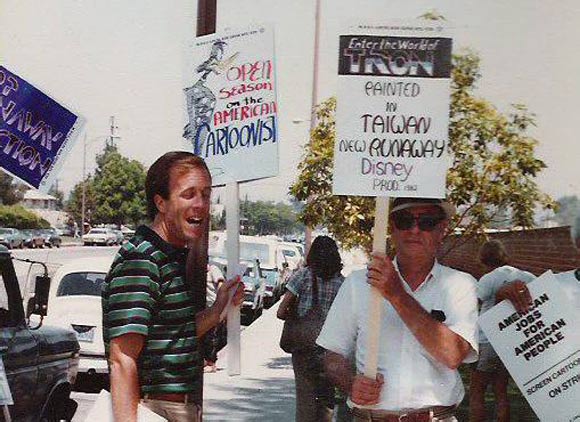

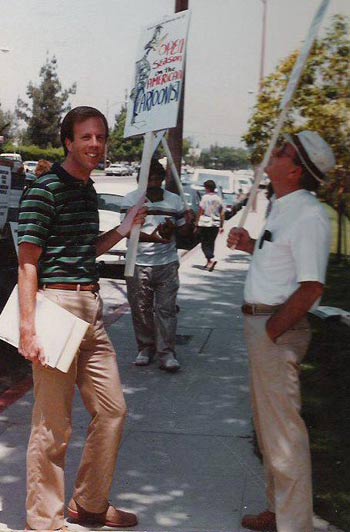

There were stacks of picket signs leaning against a brick wall, with men I assumed to be union volunteers handing them out. I grabbed one that had Daffy Duck and the words “Open Season on American Cartoons” drawn across it.

“Nice looking duck,” said a familiar voice. “But the wrong studio.” It was story artist Vance Gerry, standing four feet away from me in sunglasses and pork pie hat, holding a picket sign and smiling.

“Custom-made, ” I said. “Have you done this strike thing before?”

Vance shook his head. “First time.”

“How long you think it will last?” I asked.

“No idea. But the union says we need to be out here, so we should be out here.”

People were snatching up signs as they came out the gate and falling in the long, moving line of picketers…just as if they’d been pulling strike duty all their lives. On that first day, most Disney animation employees marched at the studio entrances on Alameda and Buena Vista. I hiked from one group to the other, buzzy with adrenaline, encountering Disney animation staff I had never met before.

The ink-and-paint department, located in its own building, was out in force. Most of the painters were young and female, and I chatted up a pretty, blue-eyed girl who seemed serious about supporting the union. She turned out to be the daughter of veteran Disney animator (and former union president) Charlie Downs; over the next couple of months, she became one of my motivations for showing up for regular picket duty.

A year later, we got married.

At the start of the ’82 strike, most Disney animation employees thought the picketing on Buena Vista Street would last five or ten days, and then we’d all be back to work. People signed up for a few hours of walking two or three times a week (if you were smart you did it in the morning when it was cooler). But as one day bled into the next, some artists took temp jobs. Ruben Aquino, then an aspiring animator, used his copious free time to work on a personal animation test. Vance Gerry focused on his side business publishing limited edition art books.

Three weeks of picketing came and went. Trudging up and down Buena Vista Street in mid-summer with a sign was hot, monotonous work. I took a previously-scheduled vacation and got two weeks’ wages from the studio, which I needed. (They don’t pay you for picketing, but they hand out money for studio-sanctioned time off, and I had applied for the vacation before the strike). When I got back, people were still plodding back and forth outside the Disney gates, but cheerful small-talk was no longer heard on the picket line. The mood had changed from optimistic to grim, and people mostly exchanged tense gossip about whether we were near an agreement or not.

Time kept plodding on. I was picketing three times a week, going to the gym a lot, and living on salads because vegetables and salad dressing were cheap. Between the exercise and the diet, I lost so much weight people thought I had some wretched wasting disease.

Despite the vacation money, my bank account was steadily melting away. Eager for information, I took to hanging out in the lobby of the union’s office building, asking union officials if we were getting closer to a deal. The answer was always the same: There was a lot of talk across the negotiation table, but little progress.

One afternoon, seeking a change in my sign-carrying environment, I drove to Hanna-Barbera to picket. There was talk on the line about artists scabbing for H-B, working at home on storyboards and messengering them back to the studio for a fat paycheck. Union president Mo Gollub, a layout artist for Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera, sidled up to me as we walked our tedious circle, asking who I was and where I worked.

I told him. He then asked me what I did. “I’m a writer,” I said.

He shook his gray head. “Not much we can do for you.”

What an ego booster, I thought.

Most labor actions have their high points and low points, and the Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists strike, circa 1982, was careening toward its bottom. We had been out over two months. Word was getting around that artists at different TV animation studios were scabbing work at home, but Disney strikers had no work to scab. All the animation, all the storyboards, all the backgrounds and layouts and character designs for the features in development were sitting quietly on desks inside the animation and ink-and-paint buildings. No studio messengers were spiriting drawings away for absent artists to work on in their bedrooms. The studio kept everything inside its walls.

Meantime, the Disney animation staffers outside the walls were getting restless. A couple of artists went to studio management, asking if there was some way they could go back to work. Studio management referred them to non-studio lawyers who told them they could resign their union membership and cross the picket lines…without fear of reprisals.

The information went through the strikers’ ranks like pork through a goose. Union officers, realizing that solidarity was crumbling, scrambled to call a meeting at the Screen Cartoonists’ second-floor hall. Disney personnel (me included) showed up en masse.

The room was packed, and crackling with tension. A Disney assistant told the group what she’d found out about crossing the picket line from the lawyers. Several artists asked the union’s lawyer if it was true that people could resign from the Screen Cartoonists and go back to work without penalties. A long, thoughtful pause was followed by the word “Yes.”

The following day, resignation letters from Disney employees started to come into the union. The day after that, business rep Bud Hester and president Mo Gollub were ordered to a meeting with the International president Walter Diehl, where they were curtly ordered to call off the strike immediately and send everyone back to work. Hester and Gollub were told to forget about trying to hang onto the runaway clause, and negotiate whatever deal they could get. (In other words, “Do Not Pass Go, Do Not Collect $200.”)

I had become a lurking presence at the Screen Cartoonists, and was sitting in the lobby when Mo and Bud came back from their dressing down by president Diehl. Both of them looked ashen. When I asked what had happened, Mr. Hester told me. He had a tough time getting the words out.

“So we’re done?” I said. “It’s over?”

Bud and Mo nodded. They seemed ready to cry.

“And we’ve got nothing to show for it?”

“Nothing,” Bud said.

Ninety-six Disney artists resigned from the Motion Picture Screen Cartoonists and went back to work two days before the union announced that the strike was over. I was among the fifty percent of the staff who didn’t resign.

The cartoonists strike of ’82 was longer than the infamous 1941 edition, and involved more people. But the wounds didn’t go as deep, and there was less residual anger and animosity. Post 1982, few artists spent years bearing grudges.

Eight days after everyone came back to their jobs, I was sitting on the commissary patio eating lunch when an animator who’d resigned and returned inside early came up to me with his head down.

“You mad at me?” he asked. “For going back before it was over?”

“No, Phil, I’m not. Everyone does what they feel they need to do. What’s the point being angry? Life goes on.”

He looked relieved. “Okay, then,” he said. “Thanks.”

Phil walked away, never bringing up the subject of the strike again. He’s retired now, and out of the business. And he’s probably forgotten he ever resigned his union membership in the first place.

Life goes on.

.png)