‘Mouse in Transition’: Cauldron of Confusion (Chapter 10)

New chapters of Mouse in Transition will be published every Friday on Cartoon Brew. It is the story of Disney Feature Animation—from the Nine Old Men to the coming of Jeffrey Katzenberg. Ten lost years of Walt Disney Production’s animation studio, through the eyes of a green animation writer. Steve Hulett spent a decade in Disney Feature Animation’s story department writing animated features, first under the tutelage and supervision of Disney veterans Woolie Reitherman and Larry Clemmons, then under the watchful eye of young Jeffrey Katzenberg. Since 1989, Hulett has served as the business representative of the Animation Guild, Local 839 IATSE, a labor organization which represents Los Angeles-based animation artists, writers and technicians.

Read Chapter 1: Disney’s Newest Hire

Read Chapter 2: Larry Clemmons

Read Chapter 3: The Disney Animation Story Crew

Read Chapter 4: And Then There Was…Ken!

Read Chapter 5: The Marathon Meetings of Woolie Reitherman

Read Chapter 6: Detour into Disney History

Read Chapter 7: When Everyone Left Disney

Read Chapter 8: Mickey Rooney, Pearl Bailey and Kurt Russell

Read Chapter 9: The CalArts Brigade Arrives

When one studio project ends, studio staffers often get nervous, wondering if they will be around for the next one. Worrying that even with a new picture, they’ll have to endure a long layoff before the new movie gets up to speed.

Jockeying for slots on a production is always nerve-wracking, and always part of the process. And even at Disney Feature Animation, which was generally regarded in the 1970s and ’80s as an island of stability, there were layoffs, firings, and long hiatuses.

Ever since the major Disney Animation down-sizing after Sleeping Beauty in the distant time of 1958, assistant animators and in-betweeners had been routinely let go between pictures. The Disney story department had (mostly) not had layoffs, but I was still a relative newbie and remained edgy about getting pink-slipped. So when The Black Cauldron got ramped up, I worked hard to clamber onboard the development bandwagon.

The studio had owned the rights to The Chronicles of Prydain, a five-book series by Lloyd Alexander, for a decade, and lots of animation staffers had worked on it. Don Bluth had taken a run at the property when he was being groomed to be the next Woolie Reitherman, and Tad Stones (his showrunner career at Disney Television Animation still ahead of him) wrote several treatments. But as The Fox and the Hound wrapped up, studio chief Ron Miller was getting serious about having a top-flight, big-budget animated feature produced from the material, something that would rival Sleeping Beauty.

I heard rumors through Studio Gossip Central (otherwise known as Pete Young’s room) that the studio didn’t want to leave the writing assignment to some green nincompoop (me), and was seriously considering bringing in an experienced British screenwriter. In the meantime, Vance Gerry had been recalled from an extended leave that he’d requested. He was asked to go through the books and put together “beat storyboards” that would visually outline plot, action, and various set pieces. Mr. Gerry, on top of being a brilliant storyboard artist and designer, was also fast. (Story veteran Ed Gombert, no slouch in the talent and speed categories himself, once said to me, “Vance gets more boarded in a day than most of us get up in a week.”) True to form, Mr. Gerry quickly had a rough continuity in hand and was pinning story sketches to corkboards at a merry clip.

Like I had done in the early days of The Fox and the Hound, I showed up uninvited to offer gag ideas, character ideas, and bits of business. Vance liked a few of them and worked them in. It wasn’t long before he had a first pass up on boards and was showing the results to Ron Miller and a chosen few from the animation department’s hierarchy.

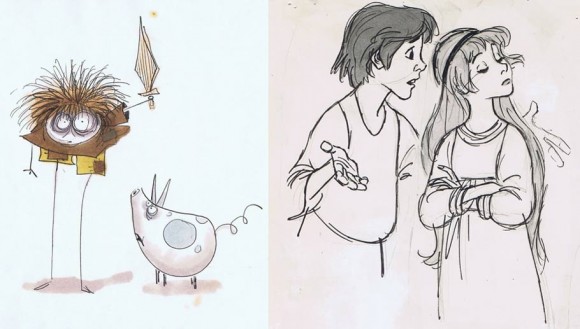

Vance had taken sections from the first couple of books, set up his principle players (Taran the pig keeper, Dalben the wizard, Eilonwy the Princess, Fflewddur Fllamm the minstrel, and Gurgi the hairy little beast) along with supporting cast, and set the plot in motion with his usual flair and efficiency. He made the villain—the fearsome Horned King—into a big-bellied Viking who had a red beard, fiery temper, and steel helmet with two large horns. Vance thought having a bigger-than-life villain with an explosive personality would get the most out of the scenes he was in, and was a sure-fire way to enliven the feature.

Pete Young was the next board artist onto the project,, and sequences started to get fleshed out. The front office finalized its deal with writer Rosemary Anne Sisson to write a script. I was disheartened that I wasn’t the scribe chosen for the job, but I could understand management’s position: They weren’t going to let some novice be the lead writer on a project that was going to be done in wide-screen 70 mm (the first since Sleeping Beauty) and would cost way more than the twelve million bucks shelled out for The Fox and the Hound. Ms. Sisson had a distinguished track record and pedigree. I had a dog picture.

The first director assigned to The Black Cauldron was CalArts alumnus John Musker, who had until then worked on the first floor with the likes of Henry Selick, Bill Kroyer, Jerry Rees, and other CalArts grads. John was assigned a couple of sequences inside the first act, and went to work expanding them.

The studio’s other feature directors—Richard Rich, Ted Berman, Dave Michener, and Art Stevens—were still finishing up Fox and the Hound. As that film wrapped, Richard, Ted, and Art swung over to Black Cauldron; within weeks disputes began to percolate on the second floor of the Disney Animation Building.

The newcomers had issues with Vance’s version of the villain, deciding he wasn’t frightening or villainous enough. They also had issues with John Musker’s development of early sequences. Too comedic, they thought.

Studio chief Ron Miller realized that there were too many cooks fighting over the soup, and that he needed somebody who could bring order to the kitchen. He wasn’t convinced that Art Stevens was right for the task, so he picked the brains of various old-timers and new employees about other candidates. The consensus seemed to be that veteran layout artist Joe Hale was the right man for the producer job on Cauldron.

Joe had been at the studio for decades. A World War II combat veteran, he had joined Disney after art school, worked on scores of shorts and features, and performed well at a myriad of tasks over a lengthy career. Liked by almost everyone, Joe had an analytical mind and quick wit. At lunchtime bull sessions, he generally had the most astute comments about what was wrong with this or that Disney movie, and the clearest solution about how the problems should be corrected.

So it wasn’t surprising that Mr. Hale was plucked out of the layout department and put in charge of Disney’s new animated blockbuster. He brought all of us together and explained that Ron Miller had talked to him about the job, and that he wanted to make the picture fresher and different from the animated features that had been made the last few years.

John Musker, Pete Young, Ron Clements, and I were happy to have Joe in charge. All of us thought we now had a sharp-eyed leader who would look at the work in progress and come to the right decisions about what storyboards, what character designs, and what story development was right for the picture. I remember one conversation with Joe in particular. He was looking over a sheaf of visual character suggestions from Tim Burton. All of the drawings were angular, edgy, and out there, more in the style of Nightmare Before Christmas than Snow White or Cinderella. “These are wild,” Joe said. “I wish there was some way to get designs like these into the movie.”

Encouraging.

But the idea that The Black Cauldron was going to have some new, groundbreaking look soon faded away. The directing crew from Fox and Hound lobbied for a Sleeping Beauty-style approach, and Milt Kahl was recalled from retirement to create character designs for Taran, Eilonwy, Fflewddur Fflamm, and other principles. They were all beautifully drawn and expertly done, but they were light years from the sketches Tim Burton was doing.

Joe Hale knew there was a schism inside the story development team. John Musker and most of the board artists were on one side of the divide; the directors from The Fox and the Hound were on the other. Mr. Hale, after attempting to forge a compromise, came down on the side of the more veteran directors. One of the early casualties from the “beat boards” was Vance Gerry’s treatment of the Horned King. Out went the rotund Viking with bushy beard and loud disposition; in came a thin, hooded, spectral presence with shadowed face and glowing red eyes.

Month by month, the storyline got darker and further away from the books. Taran and Eilonwy acquired the looks and costumes of earlier Disney characters. Eilonwy had a dress and light hair that made her resemble Aurora from Sleeping Beauty. In fact, she could have been Briar Rose’s daughter.

The younger staff grumbled, but the picture lurched along. Then Art Stevens decided to hang up his long Disney career and retire. And Pete Young related how screenwriter Rosemary Anne Sisson seemed to be having creative differences with the producer and directors, but she finished her writing assignment and moved on. Hale brought in seasoned story artists Dave Jonas and Al Wilson, and sequence boards began disappearing from the twenty and thirty-somethings’ offices. This included the room occupied by first-time director John Musker.

“I knew it was over,” John said, “when the sequences I’d been working on vanished from my walls and I didn’t have anything new assigned to me. That was sort of a hint.”

Usually story reels get better as a picture reaches closer to completion. Characters become better delineated, plot points grow clearer, and business gets more focused as animation is cut in. But there came a point on Cauldron where the characters and story seemed to grow worse. The first twenty or thirty minutes of the opus moved right along: Taran’s yearnings and frustrations are clear, the dangers confronting the wizard Dalben get set up, and Hen Wen’s freakout and capture by the winged Gwythaints are compelling and well-staged. But then the plot gets muddy and newer characters become little more than cardboard caricatures. Some dazzling set pieces happen, but the audience doesn’t empathize with the cast or get pulled in by the story.

The Black Cauldron has its moments, but there is no satisfying whole.

By and by, most of the original crew found itself off the project and casting around for a new vehicle to avoid being laid off. Happily, one came along at the right time, courtesy of Ron Clements and Pete Young, and The Black Cauldron steamed on without us.

I had spent almost two years of my life on Cauldron, but when the feature was released into theaters in the mid-Eighties, there was almost nothing I had written that remained in the movie. The only thing I can lay claim to is a story tweak that got Flewddur Fflamm into the picture earlier, and the plot moving along a tad more briskly.

Big whoop.

The Black Cauldron ran into more problems when new studio honchos Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg arrived on the Burbank lot in late-1984. Mr. Katzenberg looked at the almost-completed film, and ordered ten minutes of cuts. Joe Hale resisted, but the feature was trimmed anyway. Maybe it helped, maybe it didn’t. Either way, Cauldron was released with the alterations and didn’t make its $25 million cost back. And it was years before the picture received a video release.

I heard through Pete’s studio telegraph that I wasn’t getting any screen credit on Cauldron, even though the union contract stipulated credit was required. Mr. Hale wasn’t thrilled that I bellyached and made a case out of it, but I managed to get my name at the end of The Black Cauldron’s credit roll along with some other misfits: “Additional story by…”

But it wasn’t all heartache and sorrow. Around the same time we were fighting over credits, Joe Hale did me a sizable favor on an unrelated matter: Getting off the time clock.

For years I had marched to the small gray shack next to the entrance gate and punched my time-card: Insert the rectangular piece of cardboard into the clock’s metal slot, listen for the KA-chunk, then put the cardboard back in the metal rack. I was sick of being a drone, tired of racing down Alameda Avenue to get inside the studio by eight a.m. so I wouldn’t get docked. I yearned to be a bigger fish who was in the magic “off the clock” category.

So one day I made my way to production manager Ed Hansen’s first-floor office to plead my case for getting the tyranny of “punching in and out” off of my back. I found myself in a hardwood chair sitting on the far side of a neat wooden desk, flashing Mr. Hansen the same empty smile I had once used on Don Duckwall.

“Ed, I was wondering. I’ve been here awhile now. Would it be possible for me to …ah…get off the clock?”

He scrunched his mouth. Narrowed his eyes. “I don’t think so, Steve. For that, you have to be paid overscale.”

“I am overscale, Ed.”

“Yes. But you’re not ENOUGH overscale.”

I could feel my face flushing. I didn’t know if Ed noticed it or not. I didn’t really care.

“So how much overscale do I have to be?” I asked.

“More than you are. It’s a rule.”

We both sat and thought about this. Finally I said, “Who makes the rule?”

“I do,” Mr. Hansen said.

I was ticked off. I went steaming upstairs to tell Pete Young what had happened, and encountered Joe Hale standing outside his office in the main hall. I stopped and blurted the exchange I had just had with Hansen.

Joe smiled and said, “Let me see what I can do.”

And the next morning I received a phone call from Mr. Hansen. “Steve, I’ve thought more about our talk yesterday. And I think I CAN take you off the clock. Starting next Monday, you’ll no longer have to punch in.”

“Gee, thanks Ed. I really appreciate what you’ve done.”

Not a word about third parties communicating with him, putting a bug in his ear. I was smart enough not to bring the subject up.

And that’s how I finally got out of running to the time shack Monday through Friday. And why I think of Joe Hale with mixed emotions. I didn’t enjoy having to fight for screen credit, but I appreciated not having to push time cards through the metal slot on top of a gray metal clock, day in and day out.