Director Theodore Ushev on Bringing ‘Blind Vaysha’ to Life in Four Dimensions

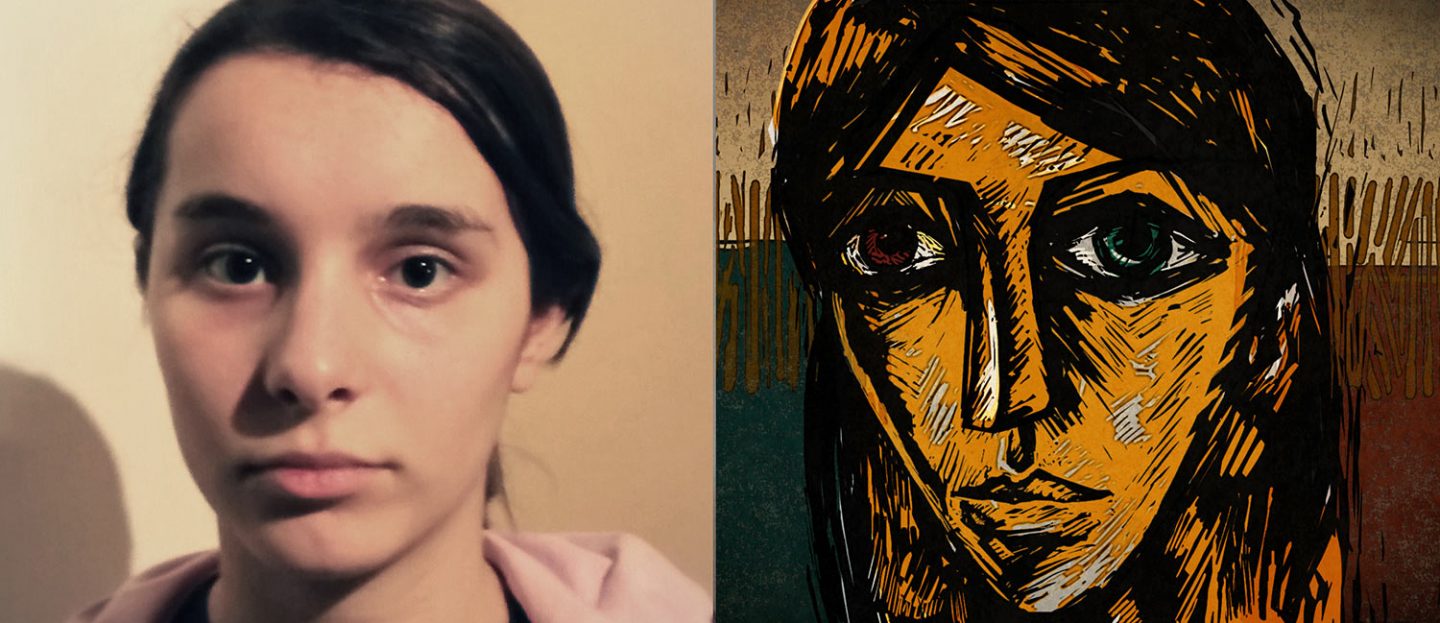

We asked Theodore Ushev to discuss the inspiration behind his National Film Board of Canada project Blind Vaysha, an eight-minute 3D short about a girl born with different-colored eyes – one that sees only the past, the other only the future, leaving her trapped and unable to live in the moment.

Here, Ushev breaks down his creative process – much of which took place in an ancient castle – and shares sketches and images from the making of the film.

The story that stayed with me

About six years ago, I read a powerful short story by a young Bulgarian writer, Georgi Gospodinov. I was working on a lot of projects at the time, but his story stayed in the back of my mind as a possible film. It didn’t come out until Olivier Catherin, a producer from France, told me about a one-month immersive writing residence at Fontevraud Abbey, in Pays de la Loire. The catch? I had to apply immediately. The only idea in my mind was Blind Vaysha. One Saturday in March 2014, I wrote the synopsis in two hours with the help of my daughter Alex, who was 13 – my French isn’t great, so we sat down together and I told her the story. She was excited, so I said, “OK, if Alex likes it, this could be a nice film.” I wanted to make a film for kids aged nine to 99. Vaysha’s story transcends all boundaries, all cultures and all eras, which is how I see human history in general.

I sent in my application; it was immediately accepted, and I went to develop the story at Fontevraud Abbey.

Isolated from the outside world in a medieval castle

I’d made some illustrations, but I had no idea how to visually tell this story. Once I got there in the autumn of 2014, everything instantly came together. Fontevraud Abbey – a Benedictine-inspired building from the 12th century – is steeped in history, and surrounded by lush landscapes. It’s where Eleanor of Aquitaine lived; she ruled all of France and all of England. She’s believed to be the first feminist, and she was extremely intelligent.

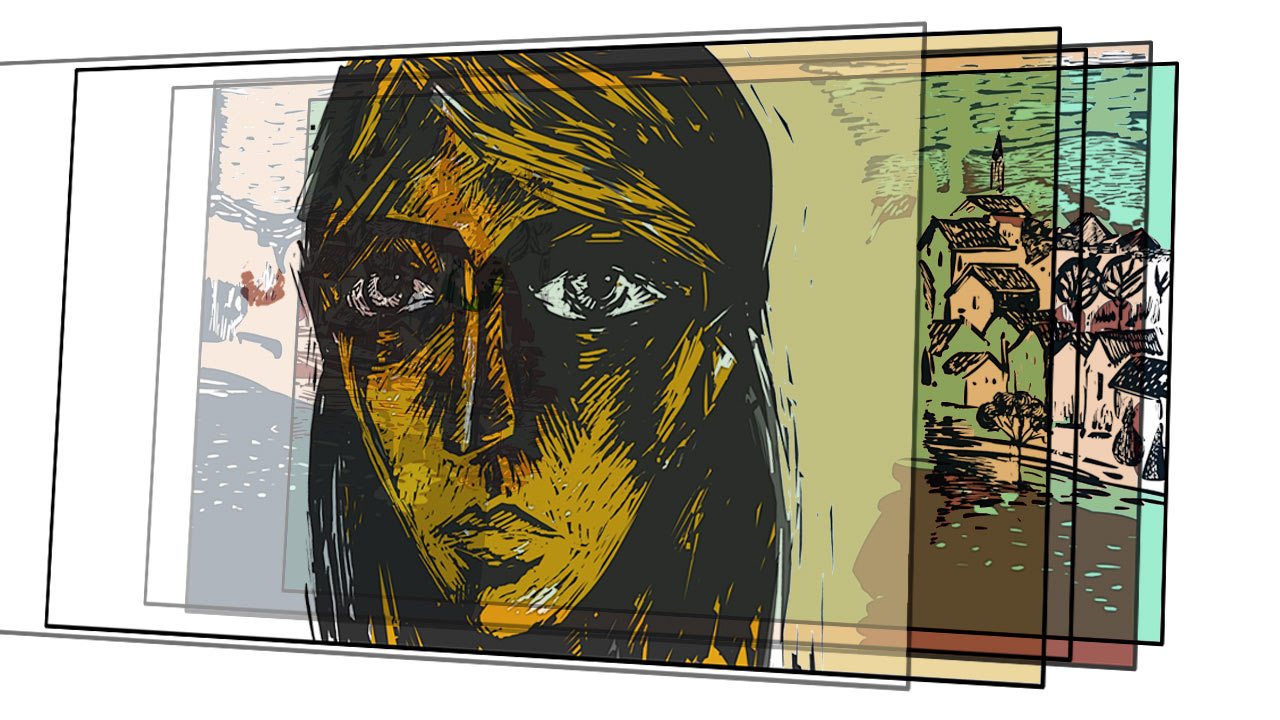

All the beautiful castles in the village – one of the largest monastic cities in Europe – served as my inspiration, along with the stained glass in the lobby of the monastery. The portraits of Eleanor, the engravings, illuminated manuscripts and frescoes all provided a clear direction and style, helping me develop Vaysha’s face and the texture of the story. All the film’s visuals come from the sketches I made at Fontevraud Abbey.

Images of the past, visions of the future

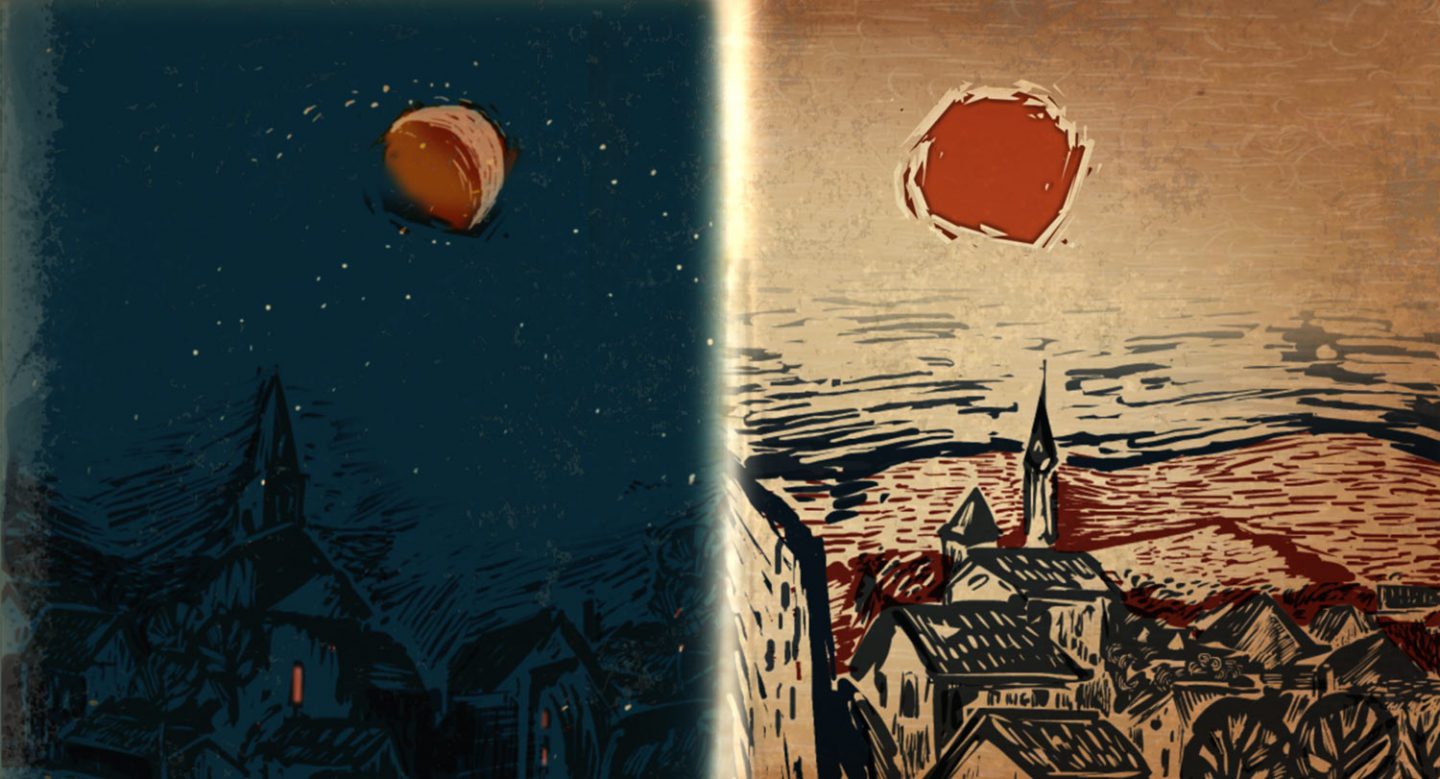

The script came together during my residence – the butterflies, the trees, the split-screen showing the past and the future. The monastery exemplified the history of the past, and at the same time, there was a huge military base in the village where every day, they were training troops and using cannons. It felt like all the elements of my film were right there. That’s how I got the idea about Vaysha seeing the violent future – all those military images. Being faithful to history is important to me.

Recreating techniques from the past

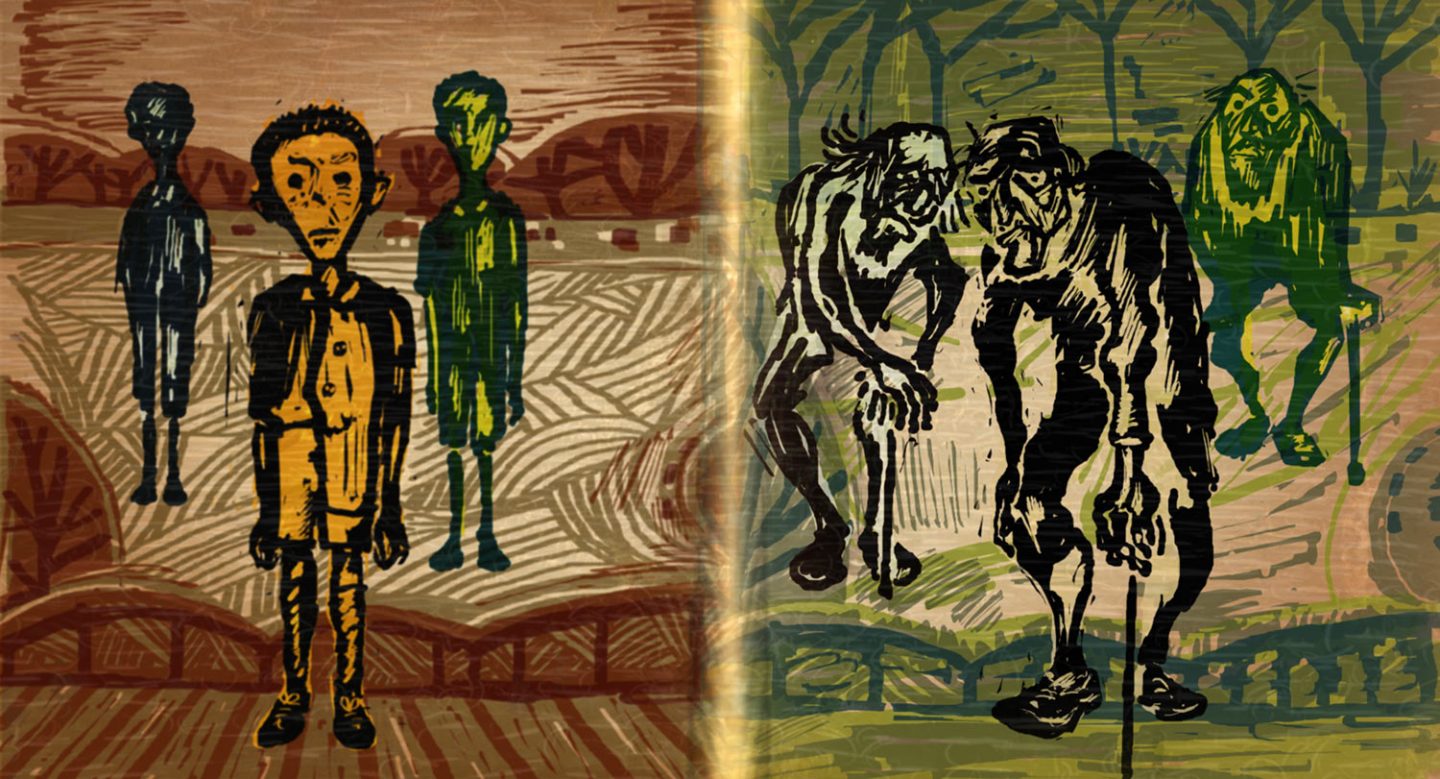

At first, I had doubts about what style I should do my film in, but it soon became very obvious to me that it had to be linocuts. The old linocuts were block prints, a cheap way to distribute popular works of art. I recreated this century-old technique with a Wacom Cintiq graphics tablet, where each color was animated separately on different layers and then superimposed to create a composition that looks like an engraving. Some of the pictures have over 64 layers, animated individually.

Where art meets technology

I don’t particularly like working in 3D, but it’s a very powerful storytelling tool. I’ve made three 3D films, but this is the first time that I’ve made a film where the 3D is part of the story itself, not just a gimmick or a device. The left and right eyes are crucial to the perception of 3D vision. I thought it would be fantastic to use that in the dynamic of the story – to show how Vaysha is looking at the world with split vision. She doesn’t see the present. In the film, when we see the world through her eyes, the only notion of the present is this white line in the middle.

I actually see this film in four dimensions. It was designed in 3D – horizontality, verticality, depth – and the fourth dimension is time, like Einstein’s theory of relativity. He was the first to measure time as a physical space. There’s no unity of time and place in this film. Vaysha tries to measure the time, but it’s not possible.

Hearing things

The other notion of the present is sound, because we hear what’s in the present. That was a huge challenge for my sound designer Olivier Calvert, because I told him, “You don’t have to hear what you see onscreen; you almost have to imagine another story that’s going on.” In animation, sound usually illustrates exactly what is happening onscreen.

This was a completely different type of storytelling. Vaysha may be blind, but she’s not deaf. When a man asks for her hand, we hear two conversations at once in her head, the past with a young fellow and the future with an old man. That’s one of the tragedies of her life, and also in ours, because we have these conversations in our own heads: while we live in the present, we’re nostalgic about the past, and afraid about what the future’s going to bring.

Movement and moments

My biggest challenge was making the animation as simple as I could. Sometimes, animators tend to over-animate. I did some scenes that were extremely over-animated, and when I started editing, they weren’t working and I deleted them. Too much action or too much movement in the film could destroy the story. I really wanted the movement to stay almost static on the screen, to create the concept of time in a box. I do everything on my own; I don’t use animators. I want the work to be as personal as possible. Every frame is like a work of art.

The second challenge was, of course, the 3D and how to play with the stereoscopy and not exaggerate it. I wanted printed sculptures, and to make unrealistic 3D, so we don’t forget that this is a fairytale. In my previous films, I tended to make things too philosophical, too complex, with too many references. For Blind Vaysha, I didn’t use any references, which is very rare for me.

Aging gracefully

I had this crazy idea – I call it the Dorian Gray Effect – that entailed constantly changing Vaysha’s face, without having her age. Dorian stayed young, but his portrait aged. Vaysha is a timeless heroine without roots. As we see many periods of her life, her face changes yet remains beautiful, so I had to redraw her face again and again for every scene so that she could look different. Interestingly, a few weeks ago, I took a picture of my daughter and when I looked at it, I realized that while making this film, I had been drawing her face as a grown-up. My daughter looks exactly like Vaysha!

Layers of meaning with music

For the birth scene, I chose Henry Purcell’s “Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary.” Gospodinov’s work often refers to there being only birth and death, with nothing in between. I wanted to evoke the past; the funeral music is from the Baroque period. For the middle, I wanted playful music. I worked with another Bulgarian friend of mine, Nikola Gruev, a great composer. Critics call his music Balkan Psychedelic. His work is very contemporary, like it comes from the future. That’s why I juxtaposed both. It’s at once very tragic, and yet very joyful.

A gentle voice

I didn’t want my narrator, actress Caroline Dhavernas, to be influenced by the rhythm of the film, so I asked her to voice both versions without any visual cues. I love when an actor brings her own rhythm and timing to the film. I asked her to read it very calmly, the way you’d read a storybook to a child, without exaggerating or playing. She got it immediately, and did an amazing job.

An interactive ending

The moral of the story is to raise the question of living now, in the present. We don’t have to let the nostalgia of the past and fear of the future destroy today. So I created an open, interactive ending: you ask the audience to think, and then decide the ending of the film.

I was thinking of the idea of a box. It came from Bertolt Brecht, the famous playwright and director, who used the “distancing effect.” He always kept the audience aware that this was theatre, not real life. That’s why I made what the audience sees as a box – a square that is 4:3 on the screen. The part Vaysha sees is full-screen, but split. But when the audience watches, it’s all in a box. The real thing is Vaysha, not what you see. I opened the screen to the audience: the film is over, now it’s up to you to decide how to end this story and how to see the world today through your own eyes.

.png)