Opinion: ‘Yasuke’ Portrays Its Black Protagonist In A Way No Anime Has Done Before

Yesterday saw the launch of Yasuke, a six-episode series from Netflix which fictionalizes the story of the eponymous historical figure, an African man who ended up fighting as a samurai in feudal Japan. The show was created, directed, and executive-produced by LeSean Thomas, the African American creator of Netflix’s Cannon Busters, and animated at the Tokyo studio Mappa. To mark its release, we reflected on the show’s portrayal of a Black character: what it does well, where it falls short, and how it differs from past attempts to tell Black stories in anime …

Characters in a lot of popular anime face prejudice and adversity, and this makes them relatable for Black viewers (as well as a general audience). Naruto in the show of the same name struggles with being branded as the demon fox, Yusuke from Yu Yu Hakusho is perceived as a delinquent, and so on. Viewers such as myself latch onto this aspect of the stories, and I find it curious how infrequently race is a part of that discussion.

It’s often said that to talk about the relative absence of anti-Black racism in anime is to map a Western point of view onto a foreign industry. This argument not only does a disservice to anime, which engages with topics like racism pretty often, but also ignores the basic fact of the African diaspora. It feels painfully obvious to say it, but yes, there are also Black people in Japan. (Racism is of course rife in other forms in Japan, and there is anime that addresses this: for example, the manga Golden Kamuy and its recent anime adaptation address the country’s history of oppression of the indigenous Ainu population.)

Yasuke, from LeSean Thomas, feels like part of a cultural shift regarding the centering of other ethnicities within the industry. It already stands out as a show about a Black character in an ancient period: mixing historical fact and fiction with sci-fi and fantasy, Yasuke draws upon tales of the real-life African samurai Yasuke, imagining his life after service to the daimyo Oda Nobunaga (which ended with Nobunaga’s death in 1582). As an anime series with a Black protagonist, it is not unprecedented — Michiko & Hatchin and Afro Samurai exist, for starters — but its willful engagement with the unwanted politicization of Black people’s bodies feels new for anime.

In the show’s present, Yasuke has probably been in Japan longer than he ever was in Africa, having arrived in the country by way of servitude to a Jesuit missionary. But his constant and uneasy adjustment to Japanese society is acutely felt, his otherness and the color of his skin treated as a constant fact of his character; the show is more interested in unpacking that permanent status than most anime. This could be partly attributed to how Thomas himself moved from the U.S. to South Korea and then Japan to pursue his career in animation.

There’s something unique about the matter-of-fact presentation of Yasuke’s otherness, itself a rebuttal to the idea that it’s unrealistic to see the African diaspora and Afro-Japanese characters in anime. Notably, Yasuke is not even the only Black character in the show: the Beninese character Achoja arrives in Japan as a mercenary, hired to capture Yasuke’s ward. But the centering of Yasuke feels special for several reasons: it seems rare to me that the African diaspora is considered in any depth in anime, explicitly discussed in situations central to the narrative, and also somewhat uncoupled from the present day.

Yasuke simultaneously fits into and conflicts with previous interpretations of Black characters in anime. The fantasy and sci-fi elements, alongside the ronin (masterless samurai) protagonist, ensure that the most immediate comparison will be with Afro Samurai, with which Yasuke shares celebrated character designer Takeshi Koike. But as Thomas himself suggested in a recent interview with Polygon, Afro, the lead in Afro Samurai, is something of a cipher, built (lovingly) from afar out of impressions of different elements of African American culture. Yasuke as a character is mostly uncoupled from African American culture; between them, he and Achoja counteract the idea of a monolithic “Blackness.”

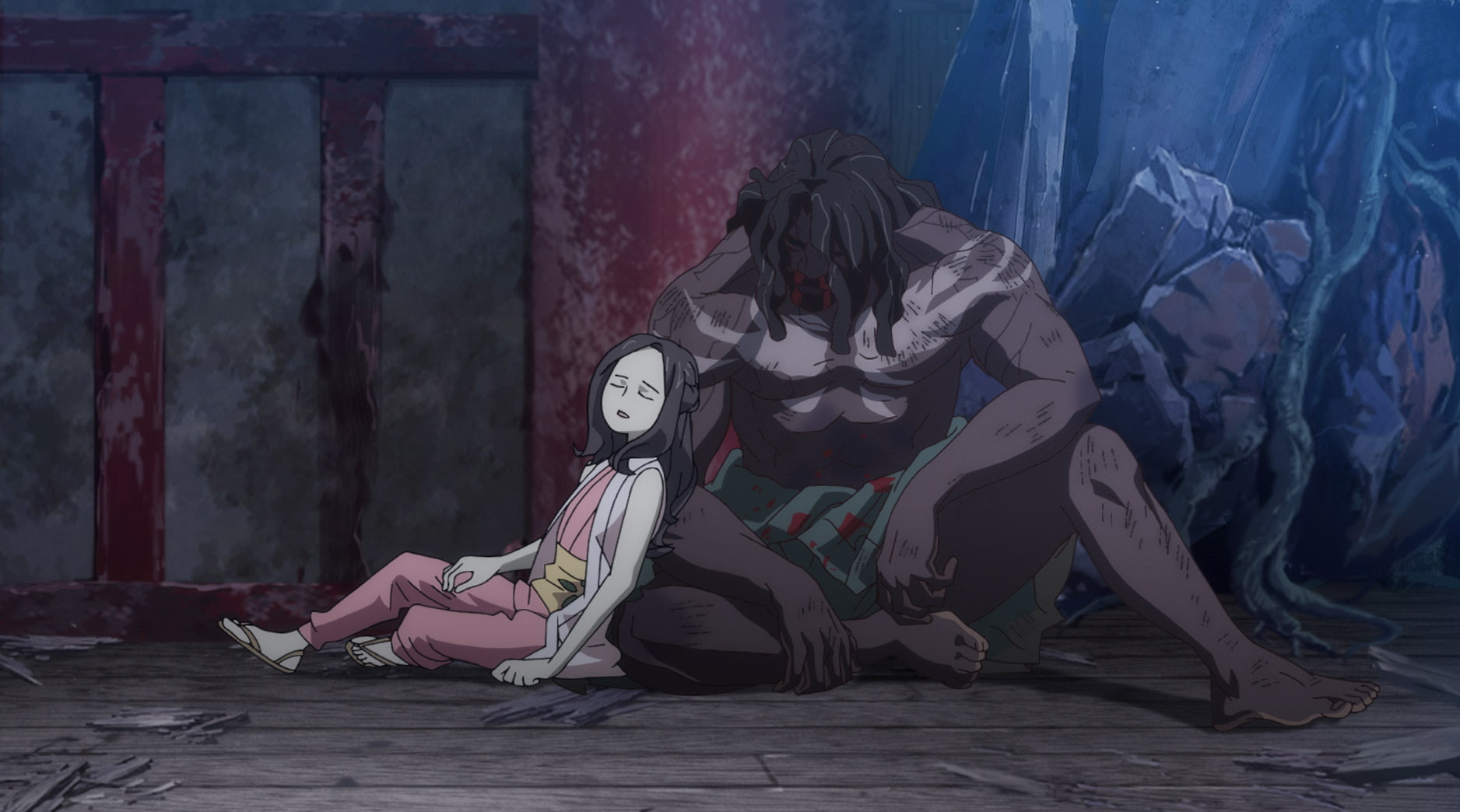

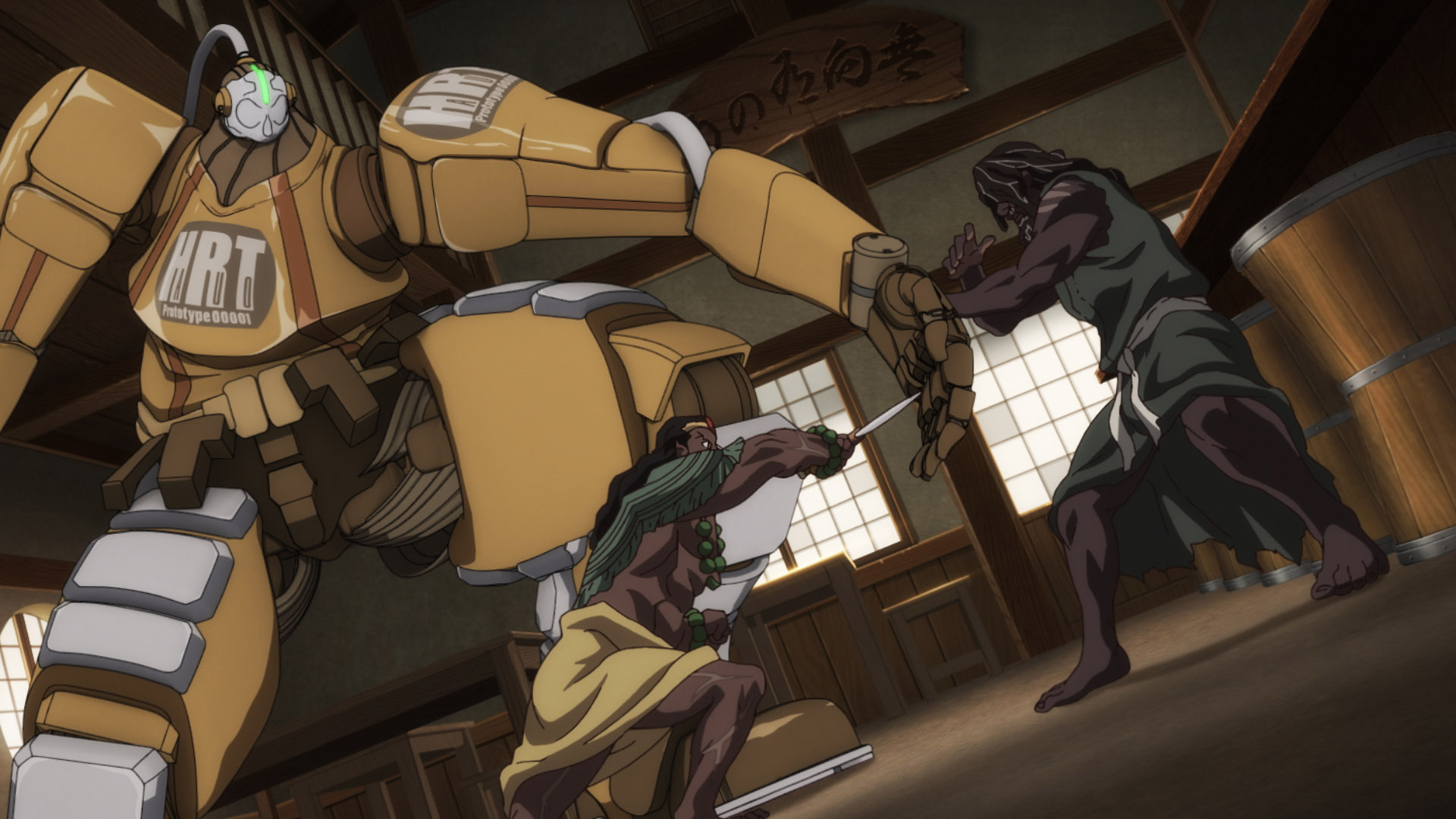

Yasuke isn’t perfect in its pursuit of these ambitious plans. Despite Koike’s striking designs, and although Yasuke the man cuts an imposing figure (he’s recorded as being over six feet tall), the visuals can feel plain outside the fights, the moments of violence depicted with more loving detail than those of peace. The art direction is pretty, the fight scenes exciting, but the stakes start to feel a little hollow as the scale of the conflict between Yasuke and his foes increases.

The show is also somewhat undermined by its choice to introduce robots and the like, as other anime works mythologizing figures from history have done before. But at least here, those robots, wolf women, and demons serve a thematic purpose, emphasizing the absurdity that people treat Yasuke, and not these other outlandish characters, with suspicion.

Even with those flaws, the show is still encouraging, simply because of whose story it decides to tell, and how. Historians speculate that Yasuke was from Mozambique, a country bordering my mother’s country of Zambia — a fact that thrills the teenager in me. It’s also refreshing to see a Black character who is not a contemporary agent of political change: so many Black heroes in the media are tied to the civil rights movement and fights for political freedom in the present.

This isn’t to say that Yasuke the character is apolitical: as a samurai fighting for a powerful, reform-minded warlord, he drives change whether he wants to or not. The show embraces the complications of his position — he does not expressly fight for political change so much as out of a sense of personal obligation to a young girl who crosses his path — but it’s important that his agency becomes his own. He steps out from simply being a samurai: a tool of enforcement, representative of someone else’s will. Starting the series as a ronin, he then chooses who he wants to help.

It’s not the case that Black, African, and Afro-Japanese people are invisible in the anime industry — far from it. There are plenty of animators, plenty of cosplayers; there are studios like the American-owned, Tokyo-based D’ART Shtajio, whose two co-founders are Black. There are caricatured Black characters, but nuanced ones too: the populace of the Cloud Village in Naruto, Atsuko Jackson in Michiko & Hatchin, Aran Ojiro in Haikyuu!, and Dorothy in Great Pretender. It’s fine not to have these characters tied to introspection about race; it’s very welcome to myself, and a lot of other fans, to be free of such agonies for a bit.

But it’s also affirming to see Yasuke deal with this history and the character’s specific ostracization, without making it the defining element of his backstory — he has a history of love and loss, and new companions to protect. Furthermore, the characters mentioned above are in supporting roles; Yasuke is the protagonist. This anime series is one of the few that get at the inescapable politicization of being someone with black skin (and sensitively so).

Black and brown fans of anime, myself included, have made the leap in imagining themselves as the protagonists for a long time already; these activities were probably instrumental in the road to making Yasuke happen. But it’s also nice to not always have to make that leap — to just look at the screen and see that you’re already there.