How ‘Becca’s Bunch’ Achieved Its Unique Blend Of Puppetry And Animation

Back in 2012, Chris Dicker saw an unusual short at a festival in Ireland. Fear of Flying was a playfully macabre tale of a bird who can’t bear to take wing — but what caught Dicker’s eye was the film’s look. Its creator Conor Finnegan had shot live-action puppets, over which his team had layered 2d and 3d animation. The result was a visual world that was at once richly tactile and highly expressive.

Dicker showed Fear of Flying to his team at Jam Media, a studio specializing in animation for young audiences, where he is head of development. With Finnegan’s involvement, Jam — which is based in Dublin and Belfast — began to develop a preschool series inspired by the film’s techniques. The story’s premise was changed to suit the audience: the queasy protagonist of Fear of Flying was replaced by Becca, a sprightly young bird who isn’t afraid of much, and she was given a new cast of animal friends. The series, named Becca’s Bunch, would follow the team’s adventures in the Wagtail Woods.

After years of development, Nick Jr. jumped on board and commissioned 52 11-minute episodes. Jam was tasked with replicating the production of Fear of Flying on a far larger scale. It contracted Manchester’s Factory studio to build the sets and puppets, and shoot the live-action sequences. The edited footage was sent back to Jam, which added animation and vfx (including the characters’ limbs and facial features), then composited the whole into the finished product. Niall Mooney, who supervised the post-production, knows of no other children’s series that has attempted this hybrid approach — much of the time, his team were working things out for themselves.

Becca’s Bunch premiered in July 2018 in the U.K., and launched in the U.S. last September. Finnegan and Mooney talked Cartoon Brew through the various stages of the series’s unusual visual production.

Step 1: Make the puppets

Conor Finnegan: All the puppets are hand-made, stitched and sewn together. There’s a foam core for the body, which is then covered in a felted wool. The wool was all spun on a traditional yarn-spinning device, then washed to varying degrees to get the right level of felty-ness! The original prototype puppets were made by Jessica Dance, an amazing artist who works almost exclusively in wool. The props — 4,000 in all — and sets were made from various materials, but again almost all handmade. There’s quite a bit of papercraft for the blades of grass, flowers, leaves, and bushes. I wanted to have a very simple, tactile style and graphic look.

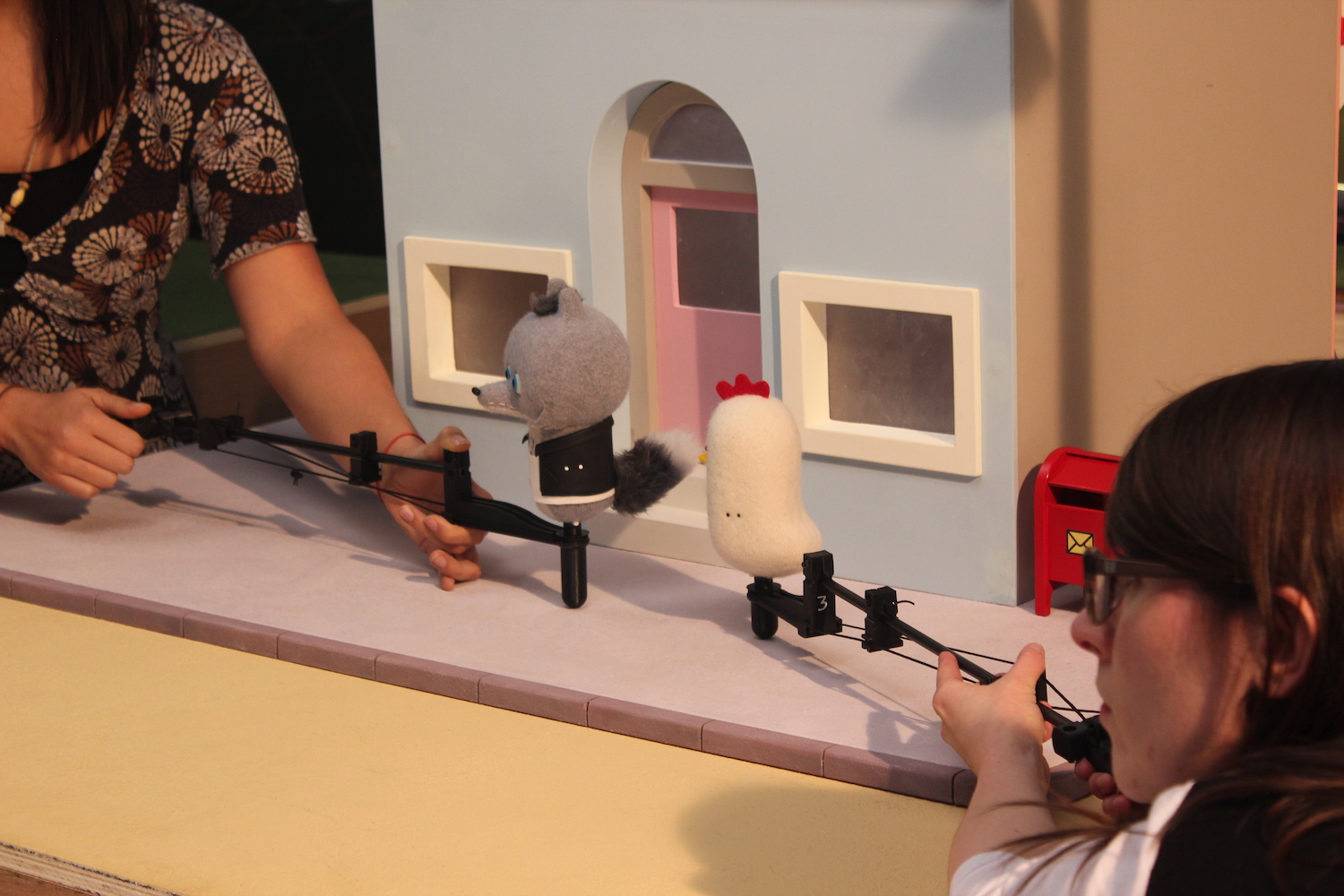

Step 2: Get the puppets moving

Conor Finnegan: We designed a rig for the puppets that consisted of a rod and oval-shaped wheel. I’d made something similar (but much more lo-fi!) for Fear of Flying. The oval wheel gave the puppets an up-and-down cadence that gave us the motion of a walk cycle. The rig also had a little dial that allowed the puppets to turn and swivel. On some sets we had removable bases, which meant the puppeteers could get below the puppets (under the sets) and puppeteer in a more traditional way.

Step 3: Shoot

Conor Finnegan: I think the hybrid look and feel of Fear of Flying was part of the selling point for the show, so we never considered going fully digital. We decided we’d shoot as much in camera as we possibly could. Having that as a guiding rule made decision-making on set much quicker. Some scenes we’d have to shoot in multiple passes. Say, if there was a crowd scene, we’d shoot maybe four puppets at a time and mark their positions to avoid any of the characters crossing over each other. Then we’d comp them all back into one scene in offline.

We managed to pull off some amazing things in camera, like action sequences involving characters running on a rolling log, scenes set underwater, and some where we shot on extra-miniature sets and cheated the scale of things. I directed the live-action shoot and wrote directors’ notes for all 52 episodes on a shot-by-shot basis. The shoot lasted 192 days altogether.

Step 4: Recreate the puppets digitally

Niall Mooney: As there were five different versions of each puppet, all hand-made and ever so slightly different to each other, object-tracking the puppets’ movements pixel-perfectly was a huge challenge. We originally tried using the standard 3d models of the characters based on the characters designs used to build the puppets, but discovered that these were not accurate enough for the tracking software.

So we looked into 3d-scanning each puppet, but with so many characters and versions of each puppet, this would have proved very costly. Instead, we shot detailed photo references of each puppet and created exact replicas through photogrammetry (using a program called Realitycapture). This technique, matched with the PF Track software, were game changers. They very quickly gave us the detailed models we needed and the tracking results were pixel-perfect.

Step 5: Remove the puppet rigs

Niall Mooney: Removing the rods and wires created initial problems. We shot blank plates of each scene without the puppets in place. This allowed us to remove the rods and wires very quickly. Hand rotoscoping was needed to clean up any areas where the rods intersected behind the puppets, and their fur textures also created the need for very detailed roto and cleanup. We had different rigs for different actions; there was never one solution to the cleanup, as it was very shot- and character-dependent.

Step 6: Add the animation and effects

Niall Mooney: The modelling and rigging were done with Maya. We also used Maya for character animation, with the fur/texturing and lighting done in Vray. For the cgi/fluid effects we used Maya, Phoenix FD, and Houdini. All the 2d animation was done in Adobe Animate, and the final compositing was done in Adobe After Effects and Nuke.

Matching the on-set lighting and integrating the cgi elements perfectly with the miniature sets and puppets was very time-consuming and required a lot of R&D. Any differences in textures, shadows, and lighting were immediately noticeable, so it really pushed us to create higher-quality renders.

.png)