Disney And Pixar Sued Two More Times Over ‘Inside Out’ Copyright Infringement

Just four months after prevailing in one copyright lawsuit over their 2015 Oscar winner, Inside Out, The Walt Disney Company and Pixar Animation Studios were named in two additional, separate lawsuits in the past weeks, both claiming that the creators of Inside Out based the film on their works.

In Nevada federal court on June 2, author Carla Jo Masterson filed suit, claiming the film was based on her book, What’s On The Other Side Of The Rainbow? (The Secret Of The Golden Mirror), as well as her screenplay, “The Secret of the Golden Mirror.” Meanwhile, a couple weeks later on June 18, Canadian director/cinematographer/editor Damon Pourshian filed suit in San Francisco, claiming Inside Out was based on his live-action student short film, likewise titled Inside Out, made in 1999-2000 while attending Sheridan College.

Masterson also names the film’s story team, including Pete Docter, Ronnie del Carmen, Meg LeFauve, Michael Arndt, and Josh Cooley as defendants. She claims that her works “depict the childhood emotions of Joy, Fear, Sad, Anger, Laughter, Friendship, Love, and Shy as characters that appear throughout the book in consistent and continuing configurations and colors.” Masterson further claims that copies of the book were included at the celebrity swag bags handed out to attendees of the 2010 Emmy Awards, the 2011 Academy Awards, and the 2012 Teen Choice Awards. Because Inside Out director Pete Docter, screenwriter Michael Arndt, and “many Disney executives” attended these ceremonies and had access to the swag bags, Masterson argues, they had access to her book.

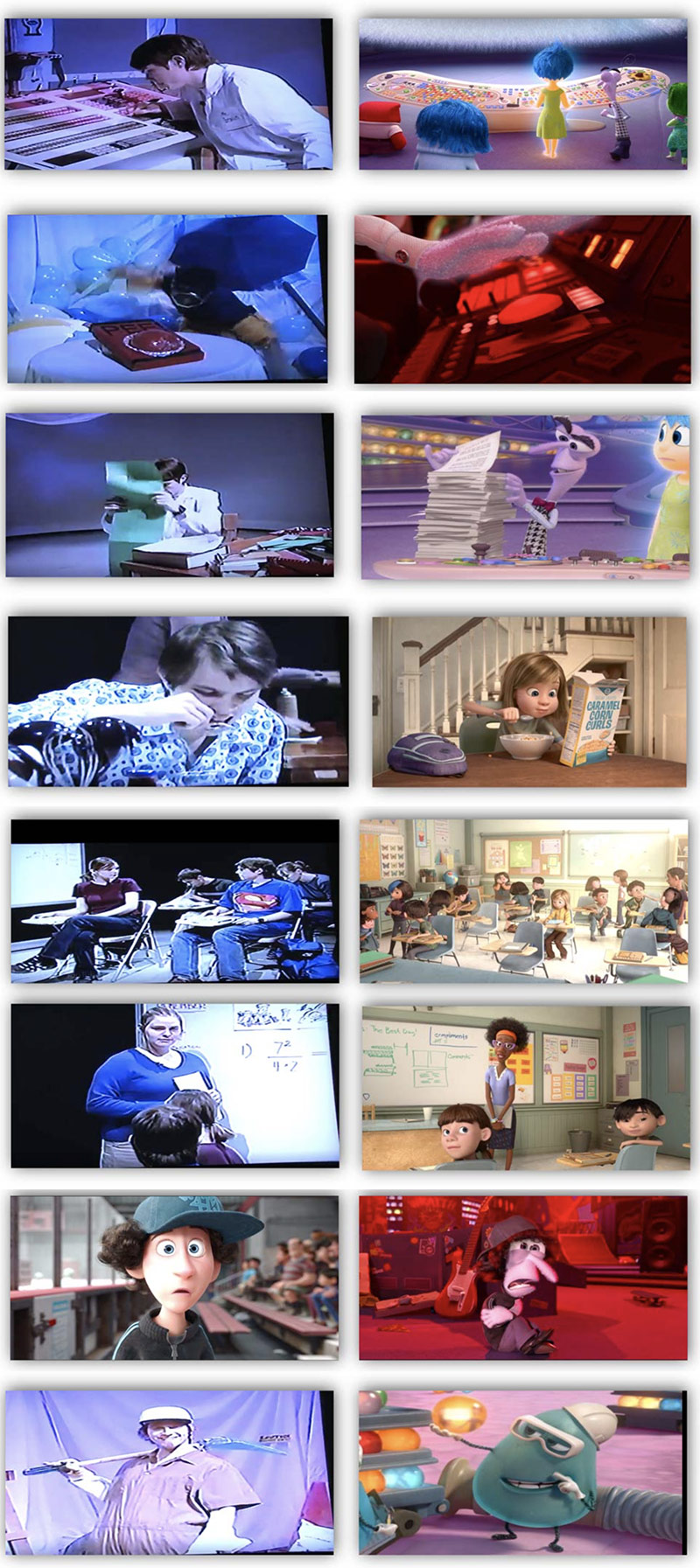

Pourshian, meanwhile, a filmmaker based in Toronto, claims Disney and Pixar based their animated film on his short, developed and produced between 1999 and 2000. Pourshian’s short “tell[s] the story of the reactions of a boy named Lewis to events in his everyday life, illustrated through anthropomorphized representations of his bodily organs…as seen from the inside of Lewis’s body.” The short shows both Lewis’s “outside world as well as an interior world in which his organs react to the outside world and to each other.” The story features the Brain, “who operates a command center using a complicated control desk within Lewis’s body,” Heart, Colon, Stomach and Bladder. “Each [organ] has a distinct personality and influences Lewis’s actions in various ways.”

Pourshian notes the similarities to how, in the animated film, the girl Riley was influenced by five anthropomorphized emotions. He also claims that, because Sheridan students saw his student film in 2000, and because Sheridan is considered a “feeder” school to Disney and Pixar, with “large numbers of its graduate to work for them, Disney and Pixar had access to his student work. Pourshian asserts that “around the time of the screenings” of his short, “Disney and Pixar were recruiting on campus.”

Pourshian spends considerable time in his complaint pinpointing similarities between the films. For example, “Pourshian’s Brain and Disney/Pixar’s Fear are tightly wound, ‘nerdy’ male characters that are both prone to panic and to consult lists, papers and books…” Pourshian points out a description of Disney/Pixar’s Inside Out from The New York Times: “Each [internal character] has a necessary role to play, and they all carry out their duties in Riley’s neurological command center with the bickering bonhomie of workplace sitcom colleagues,” and adds, “That is exactly the mood of…Pourshian’s work – each of his internal characters has a specific role to play, and, much like Disney/Pixar’s work, they carry out their duties with ‘bickering bonhomie.’”

Pourshian’s complaint goes on to highlight additional similarities, such as key scenes set in “traditional classrooms” with “neat rows of old-fashioned desks, with both teachers working front of whiteboards at the front,” lunch room scene depicting loneliness, and scenes showing the parents putting the lead characters into bed.

Disney and Pixar will likely respond that these are all mere scènes à faire – a concept in copyright law where certain types of scenes are so well established and so common that they are virtually inherent to a type of work, and so are not protected by copyright.

For Masterson and Pourshian, the stakes were raised on June 21 when the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals – which has ultimate federal jurisdiction in the region – affirmed a lower court’s awarding of attorneys’ fees to a prevailing defendant in the copyright case Shame On You Productions, Inc. v. Elizabeth Banks, et al. In doing so, the court more clearly established a basis for awarding attorneys’ fees to the prevailing party.

In that case the plaintiff, Shame on You Productions, claimed the movie Walk of Shame was based on a screenplay called “Darci’s Walk of Shame,” written by the production company’s president, Dan Rosen. The court ruled that the plaintiff had no reasonable basis for believing there was infringement – the two works were too dissimilar.

The federal court affirmed the lower court’s finding that the major similarity between the works was simply the concept of a “walk of shame” after a romantic encounter, but such a concept alone is not protectable by copyright law. Other similarities the court dismissed as scènes à faire. The court ordered the plaintiff to pay over $300,000 of the defendants’ attorneys’ fees, noting that an award of attorneys’ fees to a defendant prevailing against unreasonable claims serves to deter such unreasonable claims from being made in other cases.

Should the courts in Nevada and San Francisco find Pourshian’s and Masterson’s claims against Disney/Pixar unreasonable, Pourshian and Masterson may likewise be ordered to pay the fees for Disney’s and Pixar’s high-priced attorneys. Such a ruling could give pause to the next round of people who want to claim that a major animation studio stole their ideas.