The Wonderful World Of Cardboard In Daniel Agdag’s ‘Lost Property Office’

In a sepia-toned world, a lone man repairs an abandoned toy robot. Behind him, the towering shelves of a cavernous storage facility are crammed to the brim with umbrellas, cameras, skis, rackets, and valises of all shapes and sizes.

As loyal custodian of his local transit’s lost and found, Ed has lovingly recovered and labeled the misplaced possessions of hundreds if not thousands of commuters—but one day, he is notified that his services are no longer deemed necessary. This is the quiet, thoughtful story of Daniel Agdag’s Lost Property Office, a stop-motion film that’s in the running to be nominated for the animated short Oscar.

Agdag worked with a small, dedicated team, the core of which consisted of only three others, in order to bring his vision to life. Producer Liz Kearney secured funds (a process that took four years of applying) and negotiated music rights, while Melanie Etchell handled compositing, color grading, graphic design, and costume design and fabrication. Pierce Davison animated the majority of the film, as well as custom built the motion control equipment, and Agdag himself operated as director, cinematographer, and editor.

Agdag also built every single set and prop. Aside from the silicone and metal used for the puppets and the cloth for their garments, most of the set was constructed using over 2,500 sheets of recycled cardboard to create 1,258 unique pieces and props. Early on in the process, Agdag tried using brown paper for the puppets’ clothes, but he quickly scrapped this idea, as the paper was too fragile to animate.

“I use three different gauges, and it is a surprisingly robust material,” he says of the cardboard. “All the sets are self-supported by way of their construction, so additional materials aren’t needed for their support.”

Despite this, animation wasn’t all roses. “Cardboard is very susceptible to set shift and not the most practical material to use for animation,” Agdag admits.

Space constraints also posed a significant challenge to shooting, which was done primarily using a selection of second-hand Olympus OM manual prime lenses that Agdag had collected over the course of a year. “The room we were filming in was about three by five meters square, and the city set filled it wall to wall. It was a really delicate operation trying not to trip over [the set] or ruin the shot during filming, because there were so many different moving elements and very little space to move around in,” he says.

On top of this, he and his team had to move studio spaces three times throughout production, each time into increasingly smaller rooms.

Before Lost Property Office, Agdag was already respected as a builder of highly elaborate flying machines and other unlikely structures—all fashioned entirely using cardboard, of course. Up until recently, Agdag’s latest fantastical sculptures, some of which are vaguely reminiscent of Miyazaki’s more outlandish aeronautical designs, were on display at MARS Gallery in his native Melbourne, Australia. (In an extremely meta reference, posters with an image of one of Agdag’s creations appear in Lost Property Office emblazoned with the words “SETS FOR A FILM I’LL NEVER MAKE.”)

Agdag’s penchant for designing flight crafts is displayed in the last scenes of Lost Property Office, when Ed cobbles together an ingenious escape vessel using several of the forgotten items he’s collected over the years. He sets out on the railroad in a one-person cart that unfolds to reveal two propellers (made of skis) and a balloon that allow him to fly up and over a cardboard city, brightly lit against a starry backdrop.

While one might assume Lost Property Office’s spectacular combination of engineering and storytelling depends on the careful execution of painstakingly laid plans, Agdag says his process is decidedly more haphazard. I wanted to know, did he tend to stick to initial storyboards?

“Absolutely not,” says Agdag. “I like to play with the scenes on the day of shooting. I find, especially with stop-motion animation, being on set with the actual sets gives you a very different feeling than the two-dimensional drawings you originally conceived. I went as far as building additional elements after seeing the set prepared on stage [for the first time,] and in many cases it was far better that the storyboard arrangement.”

And though the short’s story was based on an incomplete work by friend Nicola Gunn, who writes and performs for theater, Agdag departed pretty heavily from the original idea. “After some initial collaboration, I went away and wrote the outline based off the concept and the script evolved from there,” he says. “The film doesn’t really follow the original concept at all, but I consider it the impetus for the project.”

One crucial change was to nix an entire character, namely, a bellhop friend for Ed, but with good reason. “I thought combining this companion with an article of lost property Ed finds at the train station was more economical to the narrative, and strengthens Ed’s sense of loneliness and isolation,” explains Agdag.

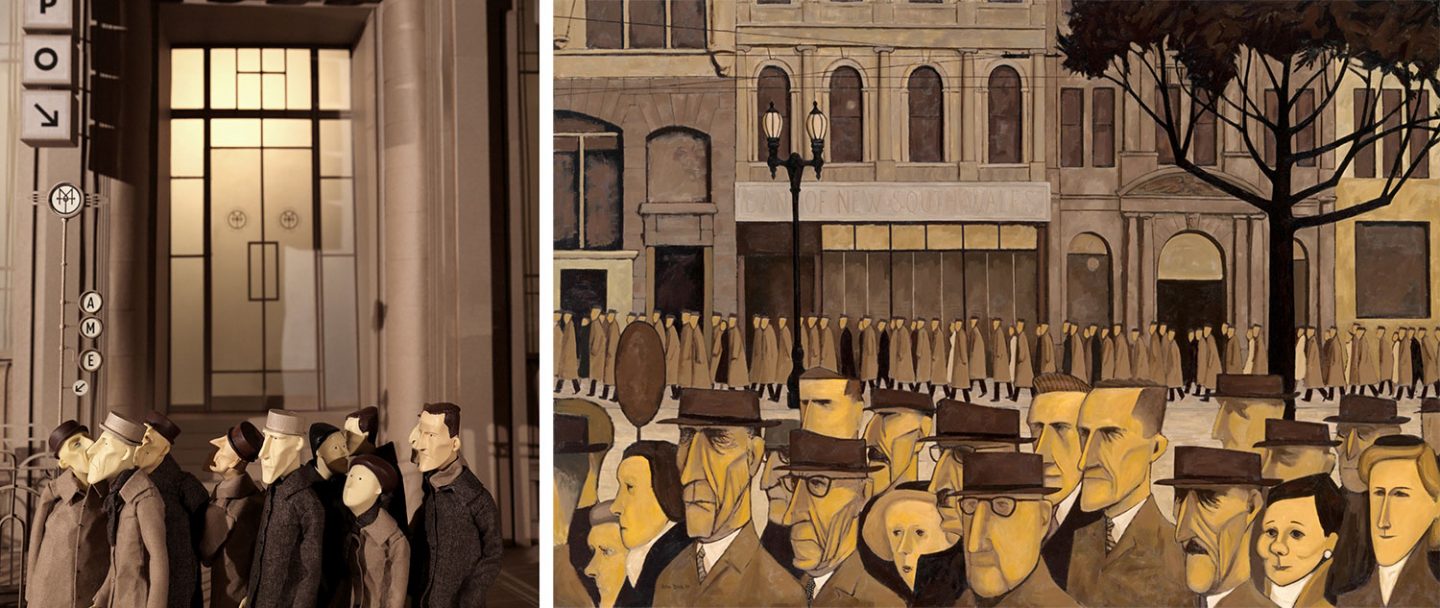

Aside from Gunn’s story, Agdag drew inspiration from several favorite artists, perhaps most notably Edward Hopper, who shares a name with the film’s protagonist. Agdag is a fan of the American painter’s iconic “Nighthawks,” as well as the works of Australian artists John Brack and Jeffrey Smart. Agdag references the detached faces in the crowd of Brack’s “Collins St., 5 pm” in the scene that precedes the short’s title card, and Smart’s “Cahill Expressway” in a shot towards the end, when Ed is making his escape from the lost property office.

“I take most of my aesthetic inspiration from painters I like,” says Agdag. “I find my imagination tends to be heightened when I’m staring at a still image in silence.”

Agdag’s thoughts on the creative process reflect his film’s somewhat melancholy feel. “It’s just a lot of time spent in the dark looking at puppets and wishing you had done more or better or different. Making an animated film feels like living life in super slow motion, and once it’s done I find it hard to remember doing it all,” he says. “The only evidence is the film itself.”