Studio Ghibli’s Steve Alpert: Disney ‘Could Have Pushed The Ghibli Films Harder’ (Interview)

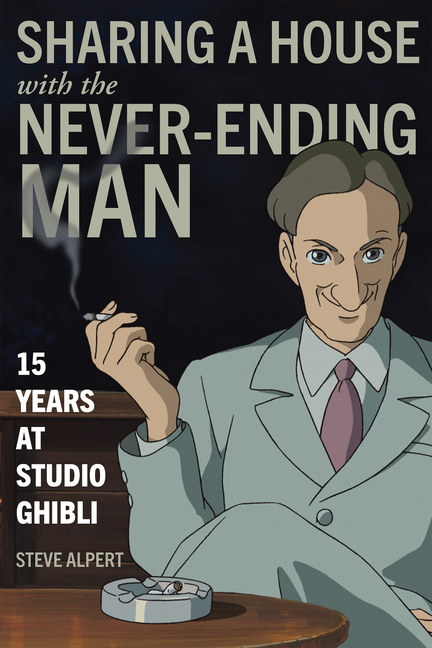

Last week, we spotlighted a few choice anecdotes from Steve Alpert’s tell-all new memoir about Studio Ghibli. The book, Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man: 15 Years at Studio Ghibli, is a wellspring of sharp insights into the studio’s creative process and fiery gossip about its main players. It left us wanting more — so we decided to speak to Alpert.

As the head of its international division between 1996 and 2011, Alpert helped orchestrate Ghibli’s ascent to global stardom. His stated role was to sell the international rights to the studio’s films and products. In practice, he was closely involved with everything from public relations to the films’ translations into English. His career at the heart of the Ghibli machine was capped by a cameo as louche spy Castorp in Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, who was both voiced by and visually modeled on Alpert (image at top).

Miyazaki is naturally a lead character in Alpert’s reminiscences — the book’s title references the director’s nickname. But some of the most enlightening passages focus on Ghibli grandees with a lower public profile. We meet Yasuyoshi Tokuma, the flamboyant, erratic chief of Ghibli’s onetime parent company Tokuma Shoten, and Toshio Suzuki, the scheming producer and marketing strategist whose shrewd business instincts have steered the studio over three decades.

Then there’s the legion of Disney executives, producers, publicists, and flunkies, who brought Ghibli’s catalogue to the American market with a mix of enthusiasm and bemusement. Alpert’s book is centered on the first five years of his tenure, when his biggest task was to help execute the groundbreaking distribution deal between Ghibli and the House of Mouse. He is unsentimental, by turns praising and criticizing both companies.

Reflecting on his early years at Ghibli, Alpert writes that his experiences fielding queries from journalists taught him “the all-important art of not answering every question someone asked.” With this warning in mind, I called him up.

How were you approached to work by Ghibli, and what did you know about the studio at the time?

I worked for Disney [in Japan] then. The company had this initiative, where they were looking for animation from other countries that hadn’t been released yet [in the U.S.]. They told everybody who worked for them in foreign countries to start looking for stuff. Studio Ghibli films hadn’t been [widely] released outside Japan then. So we began to explore that.

We just knew about the films. We didn’t know much about the studio itself. We were told that Tokuma Shoten, the parent company, were the people you had to approach. So we’d go to Tokuma Shoten and do these long, corporate-style presentations. All these dodgy Japanese guys in suits would show up, and afterwards we’d chat and shake hands, and nothing would happen. We did this for about a year and a half. What we didn’t realize is that these guys had absolutely no power to approve the thing — they were just looking for a way to get out of doing work for a few hours.

Somehow Suzuki-san found out about this, and he came to see us. Eventually, he offered me a job. I wasn’t expecting it.

You joined Ghibli shortly after it had struck its deal with Disney. For a long time, Ghibli hadn’t actively pursued global distribution. What made them change their minds?

Somebody at Tokuma Shoten had licensed Nausicäa of the Valley of the Wind [1984]. Somebody in America had cut it and changed the title [the film was released in the U.S. by New World Pictures in 1985, under the title Warriors of the Wind]. Miyazaki found out about it and was very upset.

When we [at Disney] made the offer, somebody at Disney’s headquarters said, “Tell them we’ll release the films uncut, no changes, and we’ll give them theatrical releases everywhere we distribute.” That was one thing.

The other was that Miyazaki hadn’t done a film in five years or so. Princess Mononoke [1997] was coming out, and it may be hard to imagine now, but at the time Ghibli’s Japanese distribution partners were a little concerned. They were saying, “It’s taking place in [medieval] Japan; nobody wants to see old samurai movies anymore. He’s got all these characters who are lepers, and people are going to find it offensive. There’s hands and arms being cut off.” So Suzuki-san thought this would be a good time to get some publicity by getting Disney’s imprimatur.

In your book, you paint a picture of a culture clash between Disney and Ghibli, where often they don’t understand each other’s films. You have these Disney executives mangling the Ghibli films; on the other hand, you have Miyazaki visiting Disney’s Burbank studio and calling Fantasia 2000 “really terrible.” Was there also mutual respect between the companies?

Oh yeah. When we [at Ghibli] first started distributing with Disney, we got a lot of advice from John Lasseter. He said, “The executives need to understand who this guy [Miyazaki] is, and the best way to do that is to get Disney’s animators to tell them.”

So we took a film crew to Disney Feature Animation. The crew interviewed the animators and some of the directors, so they could say who Miyazaki is and why he’s a great director. It wasn’t planned, but when we went in, all these animators had the Ghibli art books and little Totoros on their desks. They were all pirated at the time! [Laughs]

Miyazaki-san and Suzuki-san are known for being very much in control of their work, yet they’re not fluent English speakers. Once Disney’s English versions started being made, were they frustrated by the fact that their films were being translated into a language they couldn’t fully understand?

I’d say they were curious more than anything else. Miyazaki is always curious about what other people will do, and what they think he should do, sometimes. They let Disney do it to see what would happen — then they’d reject it [laughs].

That almost got us in trouble one time. I learned the hard way that there’s this legal concept in America called “constructive consent.” Disney once showed an incomplete dub of Kiki’s Delivery Service to Suzuki, and he didn’t say anything. Afterwards, when we left, he said it was terrible, and told me to reject it. But then Disney formally presented to us their lawyer’s claim that Suzuki had agreed to it, because he hadn’t objected when he saw it. And it became a big legal thing.

You write about the stress of translation, but did you enjoy it?

Yes, because it was something I’d always wanted to do. But not as much as I’d hoped. I gained more respect for how difficult it is. Translating movies is hard, because you’ve got something up on the screen that you have to match to, and there’s limitations. Also, especially between Japanese and English, there’s a lot of room for different kinds of translations — so, whatever you do, somebody will object.

What was the process for agreeing on an English title for a film?

I’d get the Japanese title and give Suzuki-san ten options — always ten — and he’d pick the one he wanted. But I could never really come up with ten, so five were usually just jokes.

Do you remember any of the unused options?

There was always “My Neigbor the Something.” For Spirited Away [2001], there was “My Neighbor Yubaba.”

With hindsight, did this marriage between Ghibli and Disney get the results you were expecting?

No, it didn’t really. Disney is obviously a huge company, and there are a lot of different people who work there. Some we got along with very well, some not so well. The first thing that happened was that the theatrical group said they weren’t going to distribute the films after all. And the video group said they wouldn’t distribute them all, because there were “objectionable” things in some of them.

So that was a problem. And when they did release the films, I don’t think they really put their best foot forward. They could have pushed harder with the marketing, done more.

In retrospect, we were lucky. We offered to buy back the films, and they said no — they preferred to hold them and not release them, which was very devastating. But — I think I mention this in the book — Mr. Tokuma wouldn’t give them digital rights. [In fact, Disney hadn’t even wanted the rights initially — they] had one of their heads of operations do a study on dvd, and decided it would never be important, so they didn’t think they needed the digital rights. When that proved not to be true, it gave us an opportunity to fix a lot of things. So we got better distributors in a lot of the other countries.

So when Mr. Tokuma later handed Disney the dvd rights, it was in exchange for your right to buy back any unreleased titles?

All kinds of things. I took advantage.

It’s crazy that Disney failed to predict the importance of dvd.

I’ve since talked to the guy who wrote the report. Technology moves really rapidly, but I think we forget the problems they were experiencing at the time. They just didn’t think they were ever going to get to the 90-minute mark on a single side. And it would probably have killed the technology if they hadn’t figured out how to get over that hump. They also had trouble solving pixelation.

In the book, you portray yourself as something of an outsider in Studio Ghibli, as the only native English speaker, and you focus on the differences between the American and Japanese ways of doing things. How close did you feel, on a personal level, to your colleagues?

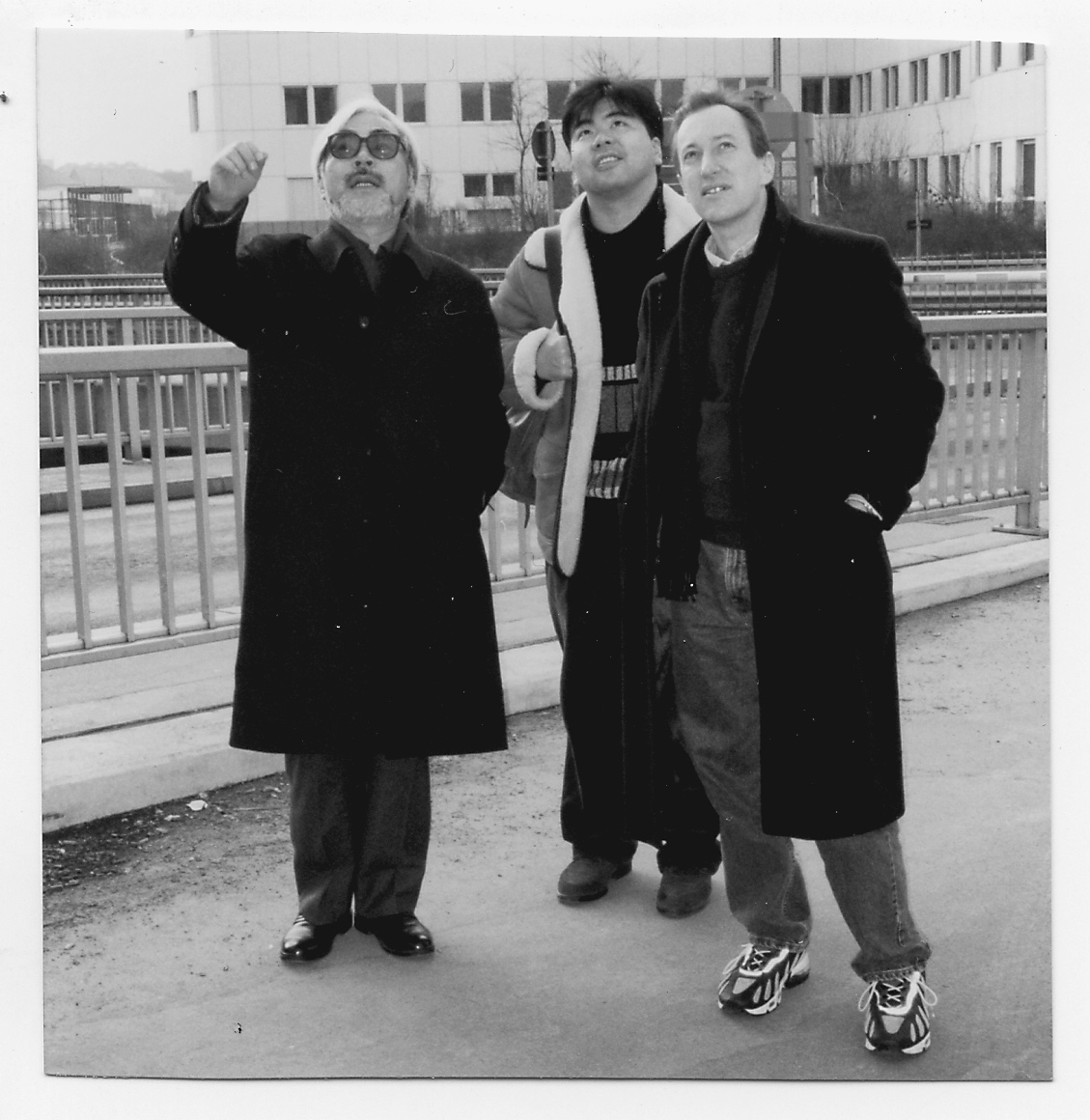

Well, it’s disingenuous to say I was an outsider, because I was on the board of directors, and privy to all the company’s main decisions. And I spent a lot of time with Miyazaki and Suzuki, and sometimes [Isao] Takahata-san, when he was around.

In a traditional Japanese company, there’s a kind of level between the people who are running the company and the people who are carrying out the operations. So with regard to the people carrying out the operations, I was a complete outsider [laughs]. I think the main thing is that no one will ever make a decision under any circumstances, and that’s pretty frustrating!

Even American companies in Japan have some of the pervasive Japanese attitudes. Like, you never leave, even if you don’t have any work to do — if somebody else is staying, you stay. I used to leave at 7 p.m., and people would say, “You’re leaving already?”

Are these the unwritten rules that allowed Ghibli to get away with breaking labor laws, as you note in your book?

No, that’s a different thing. You know, all animators want to do is sit in their cubicle and draw. They’re in heaven. That’s all they want to do — they don’t want to go home. No animation project has ever finished on time. At the end, you’re always coming to this deadline, and the only way you can finish is to grind through. That’s where we hit the labor laws. People were spending the night …

But their overtime was unpaid?

I think animators were probably on salary. It seems to me they don’t pay overtime. I don’t remember so well.

You mentioned Takahata-san, Ghibli’s other great director. He doesn’t really appear in the book — did you have much contact with him?

No, because he was retired, pretty much. After My Neighbors the Yamadas [1999], he was pretty much finished, although he did make another film [2013’s The Tale of the Princess Kaguya] — a beautiful film. But it was tough getting him to come out.

I don’t know how to say this: if you’re in a meeting with Takahata-san, you should probably bring a sleeping bag and something to eat, because his meetings absolutely would never finish. He could go on forever. That was a little tough for people who worked with him [laughs].

Once Miyazaki-san makes a decision, that’s it, he does it. Takahata-san is always questioning his decisions. With My Neighbors the Yamadas, we were recording the music, which is the last part of the film. He decided he wanted to completely change the music and start from scratch. You have to admire Suzuki-san — these two guys were not easy to work with. But he was really good at managing them and getting the films made.

Your book focuses on the period around Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away, but you didn’t leave Ghibli until 2011. Did you consider writing about the later years?

Everybody asks me that, and for some reason I don’t seem to have an answer. There was a lot of legal stuff, which is no fun to write about. But also, to a certain extent, it became a lot more routine, because the real challenge was getting everything set up [with global distribution].

Your memoir was first published in Japanese. Did Ghibli give you feedback on it?

Oh yeah. Suzuki-san and Miyazaki-san both fact-checked it. The meeting with Michael Eisner — everybody who was in that meeting read the chapter and signed off on it. [Editor’s note: the book features a remarkable account of a meeting involving Eisner, then Disney’s CEO, and Yasuyoshi Tokuma, who abruptly and colorfully criticizes Disney’s entire Japan operation to Eisner’s face.]

Mr. Tokuma was amazing. He’s really worth a book. He was a unique and interesting man. He didn’t want to have any impact on Ghibli’s creative side — he just wanted to own them — but without him, there would have been no Studio Ghibli. And to a large extent, he was important in forming Suzuki-san’s personality. Suzuki-san was his protégé.

Did spending 15 years at Ghibli change the way you see their films?

Oh yeah. I was learning a lot about the films while I was doing it. The thing that made the biggest impact on me was: whenever Disney released a film in the U.S., I had to go into Burbank and approve the color timing. The process is different in the U.S. than in Japan, and the colors don’t come out exactly the same, so someone has to sign off on it.

So I would go to Technicolor, and we’d sit in a room and look at a pristine print of an old Ghibli film. We were watching Porco Rosso [1992] in a screening room with no sound. I’d just flown in from Japan, I was jet-lagged, and I thought, “Oh my god, I’ve seen this film a hundred times, and now I’ve got to watch it with no sound.”

I was sitting there, and all these Technicolor guys were pointing out things in the film that I’d never seen. Part of it was because it was a pristine print. That doesn’t happen anymore with new technology, but with film, every time you run it, the print degrades a little bit. So if you haven’t seen it fresh off the press, you don’t see the colors the way the director envisioned them.

The guys said, “Look at how many colors he’s used! Look at all these things he’s bothered to do!” And I started to see the films in a new way. I realized it’s like watching fireworks.