‘Reruns’: The Final Chapter Of Rosto’s Dreamworld

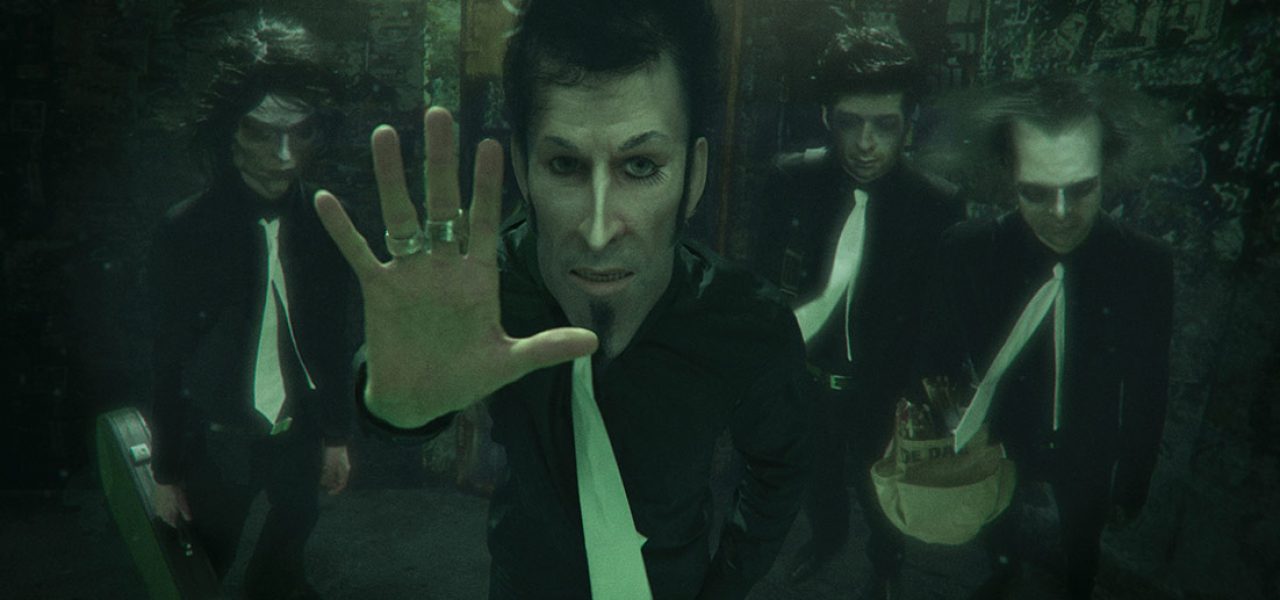

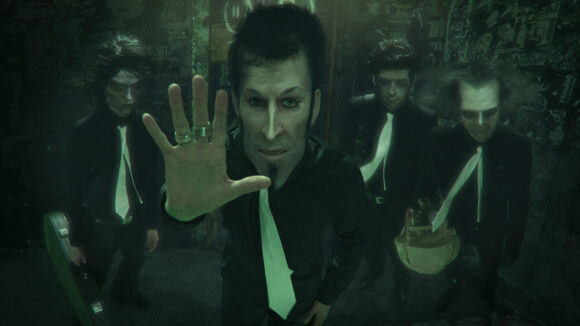

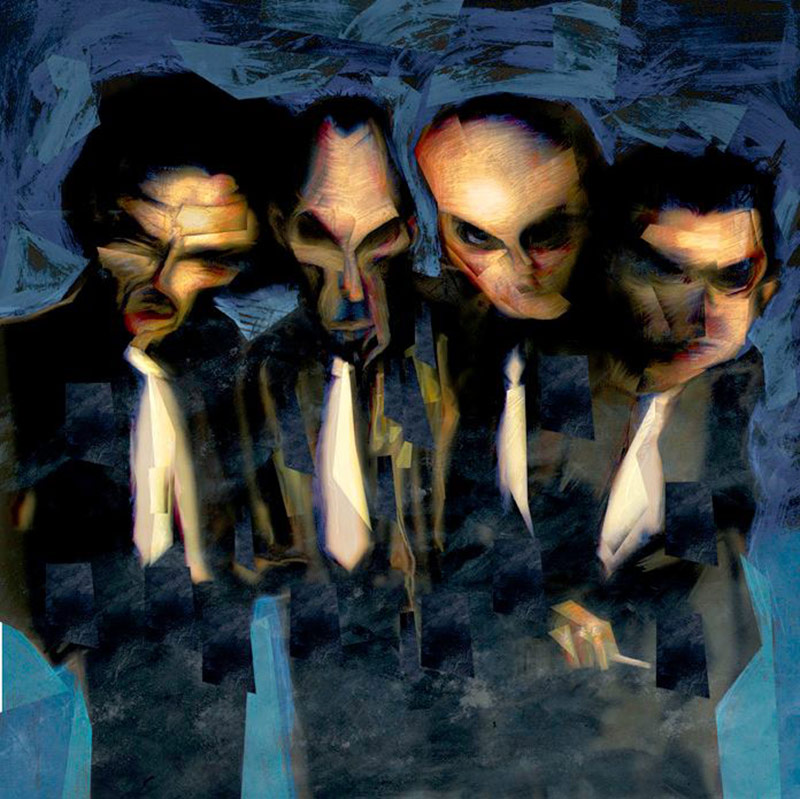

Reruns, by Dutch filmmaker and animator Rosto, concludes a tetralogy of films (No Place Like Home, Lonely Bones, Splintertime) that follow members of a rock band (Thee Wreckers) wandering through a rather nightmarish dreamscape that seems to land somewhere between purgatory and hell. Fusing live action, animation, and music (each film is based on a song from Rosto’s former band, Thee Wreckers), Rosto creates a blurred and haunting vision that skitters and skulks between the conscious and subconscious.

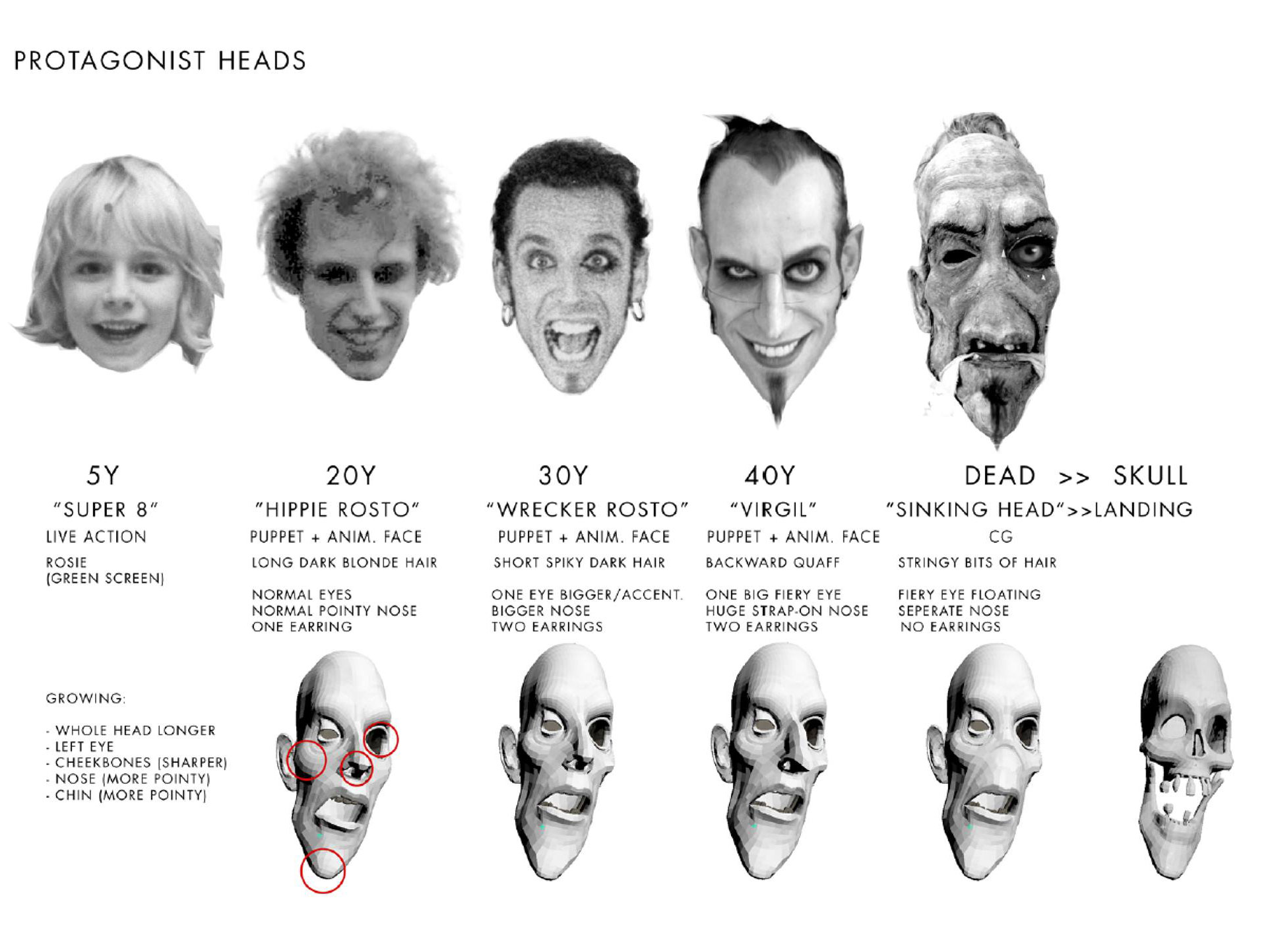

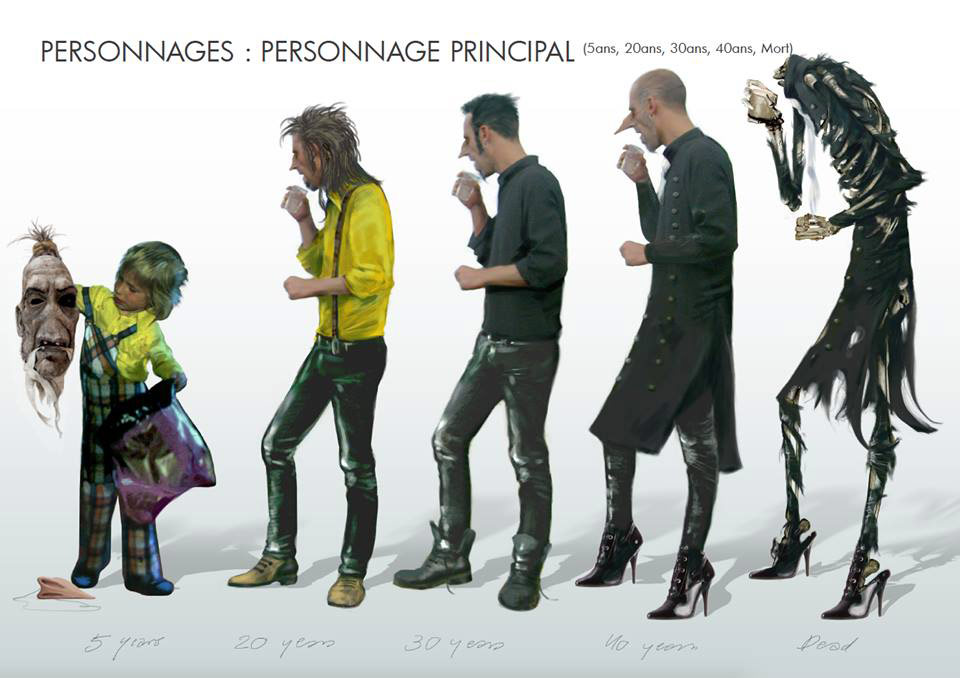

With the fates of the four band members seemingly settled in Splintertime (2015), Reruns takes up the story of Virgil Horn (whose head – which bid adieu to its body in Lonely Bones – has been carried around by the band) at different stages of his life: child, adult, old man and, yes, skeleton). Arguably more autobiographical than the previous films (Virgil bears a striking resemblance to his creator, Rosto), Reruns explores the rubbery border between dreams and memories (themselves dreamy, or as Rosto says, “corrupt” fictions) as Rosto takes us on a tour of his reimagined past. The result is an emotionally charged exploration of the complexity, potency, and ultimate unreliability of both our memories and dreams.

Rosto and I recently had a discussion via email about some of the challenges, pleasures, and themes of Reruns and the tetraology as a whole.

Cartoon Brew: Reruns strikes me as the most personal of the four films, inspired by a cloudy fusion of dreams and memories…

Rosto: Everything in Reruns is real. It’s entirely inspired by my dreams and memories. I’ve had this dream city since I was very young. It has assorted places like my old high school, art school, my studio, and my grandmother’s house. The city keeps growing. I could almost make a map of the space. There’s also this end of the world part, a big ring road that goes around the city. There’s nothing beyond it and it’s really not a very good place.

As visually striking as Reruns is, the sound seems to carry equal if not more importance throughout.

Rosto: As much as my intent was to build this dreamworld and invite the audience inside, it’s not really possible given the various constraints. In the end, it’s still 2d, it’s a screen. It’s not vr, but the sound can bring you, can surround you, and make it a more immersive experience.

Was each film based on a pre-existing song? If so, can you talk a bit about that process of translating a song into a film. And out of curiosity, did you use the original recordings or did you go back and re-record any of the songs, and if so, did the films then change the songs in anyway?

Rosto: A beautiful process. I love it, because we’re going back to pure intuitive filmmaking here. All the elements of the music are there for me to use (or not), so it’s a real luxurious position to be in. (I often realize this when I see a non-musician struggling with getting their film together. It’s best compared with making a new symphony with elements of sound, story, picture, music, mood etc.)

Simplest example always is: If you already have a “lead” in the image, you usually don’t need a “lead” in your soundtrack (usually the vocals of the song), so you get rid of one in your new composition.

There’s a lot of “feeling” and dreaming during this process (like with writing a song, this is not a very “brainy” process), which makes it so wonderfully gut-oriented. Most of the times it’s about stripping. Killing your darlings. Losing tracks. But for Lonely Bones and Splintertime I actually had to go back to the recording studio to record new tracks for the new film arrangements. This didn’t change the songs anymore (as the earlier films HAVE done) since the album’s songs were practically all laid down by now.

Water has a strong presence throughout the film, it really enhances this experience of roaming through someone’s subconscious and there’s the feeling of gasping for air, of struggling to breathe and to stay alive. In fact, that’s the general feeling you get with all four films.

Rosto: Water represents the past. The deeper you go, the farther into the past you travel.

There’s a striking and haunting scene early on in Reruns where we see the young Virgil (and also a young Rosto) roaming around an old house. It combines actual old home footage, but with effects added (it’s a nice touch that your daughter, Rosie, also portrays the character in some scenes). At one point, it’s almost like the footage is projected on various walls of an old house, which nicely touches upon that idea of these memories we ourselves project onto spaces. I can remember when our family was preparing to sell my grandparent’s home. I’d spent many happy times there and the last days in the emptied house were quite emotional. During those last hours, I’d find myself staring at blank walls and empty space while being transported back the past through an assortment of vivid memories (likely distorted over the years) from my childhood.

Rosto: My father took this Super 8 footage in 1974 in my grandmother’s house. I was 5 years old. Her house was an important location and I wanted to portray it. I used this stitching technique to mix together some of the old footage. It was like washing a black window…and then slowly the room appeared. The technique also created these echoes which complemented the idea of people slowly vanishing. The room still exists but unfortunately some of the people do not anymore.

Did you always envision a quartet of films?

Rosto: It was never about “story” as much as it was about creating my own platform for my own tunes, creating my own Fantasia, I guess. As soon as I finished No Place Like Home, I knew that I wanted/had to do 3 more. Everything in rock ’n’ roll comes in 4. The 4/4 beat. The Beatles. Thee Wreckers.

How much of the final work altered from your original vision? These appear to be quite challenging and complex films, both technically and conceptually, so I wonder if technical limitations ever forced you to change plans?

Rosto: No, there was no masterplan, no concept, except for the total number. The “rules” of Thee Tetralogy were that the next film picked up where the previous one had stopped, that it was musically based on a Wreckers song and it had the characters of the Wreckers (somewhere).

These films are super complex to pull off and I sometimes feel a bit frustrated that my guys (my team, who were often SO innovative over the years) never really got the credits, except for a “Visionary Award” for the unfinished Tetralogy at the Sapporo Festival in Japan. I’m mentioning this especially because this Star Wars post-guy in that jury recognized it exactly when he said: “We have been developing all these wonderful tools and all we do is make robot films with it. These guys (read: my guys) turned everything upside down and got excited with what ELSE you can do with it.” Audiences just never “recognized” the qualities, because it’s all done in a computer, innit? And nowadays we “have an app for that.”