Joanna Quinn On The Importance of “Choosing A Way Of Working That Ignites You”

With awards season over, we at Cartoon Brew are casting our eyes to this year’s short films. Over the coming months, we’ll be profiling the most interesting new shorts on the festival circuit and speaking to the people who made them, up-and-coming talent and established masters alike.

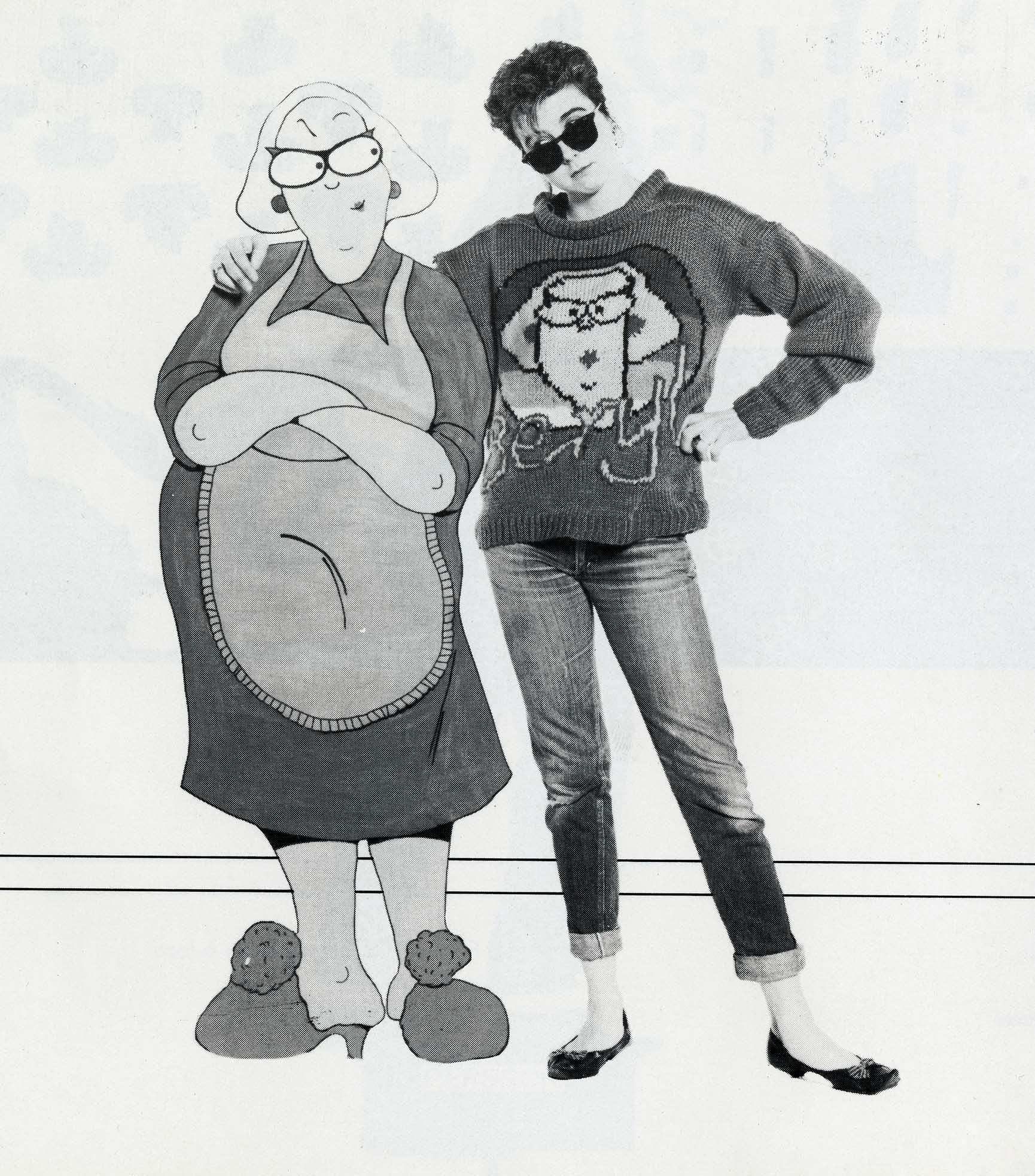

Our latest interviewee falls squarely into the latter camp. Since bursting onto the scene with her graduation film Girls Night Out (1987), which vacuumed up three awards at Annecy Festival, Joanna Quinn has remained a major presence on the indie animation scene. Her traditionally animated shorts, which include Body Beautiul, Famous Fred, The Wife of Bath, and Britannia, have earned multiple BAFTAs and Emmys, and two Oscar nominations.

Quinn’s latest short Affairs of the Art, which was written and produced by her longtime creative partner Les Mills, brings back Beryl, star of Girls Night Out and subsequent films from the pair. Now 59, the factory worker is rekindling a dormant love of drawing. Her passion for her art is mirrored in her relatives’ own obsessions with pigeons, taxidermy, and the Dutch language, among other things. The film’s uproarious scenarios are not far removed from the directors’ own upbringings, as Quinn tells us below.

Affairs of the Art, which Mills produced (through Beryl Productions International) with the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), premiered earlier this year at Clermont-Ferrand Festival, where it won the best animation award in the international competition. It is playing at Stuttgart International Festival of Animated Film, which begins today.

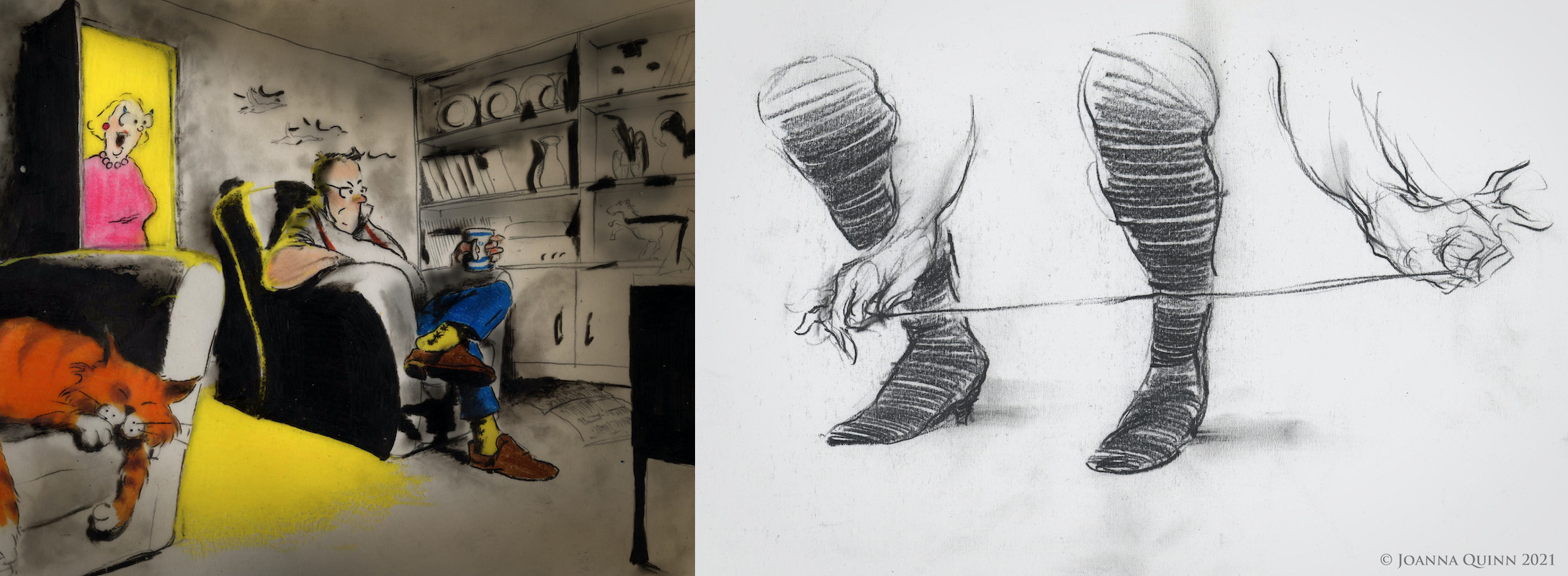

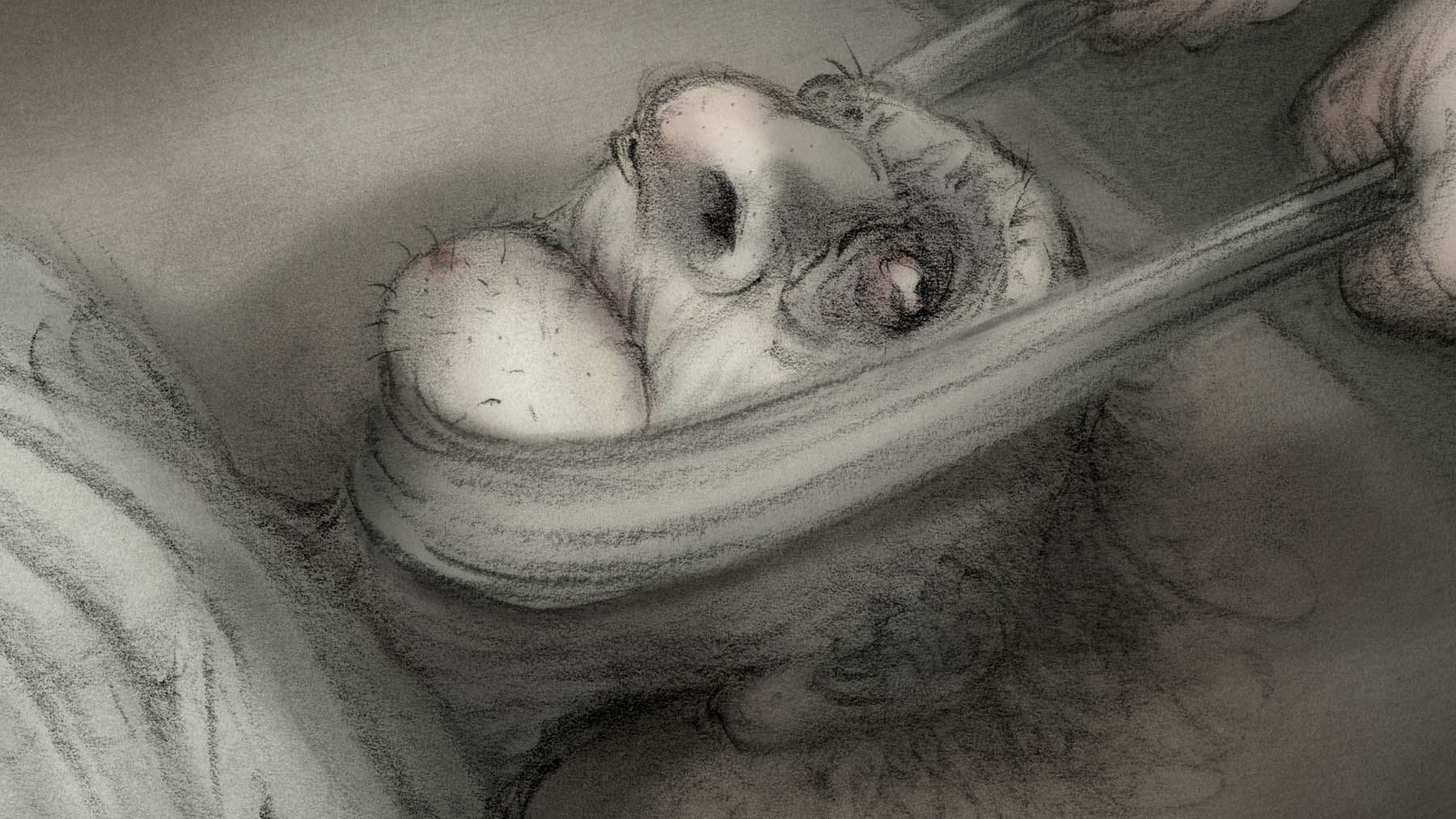

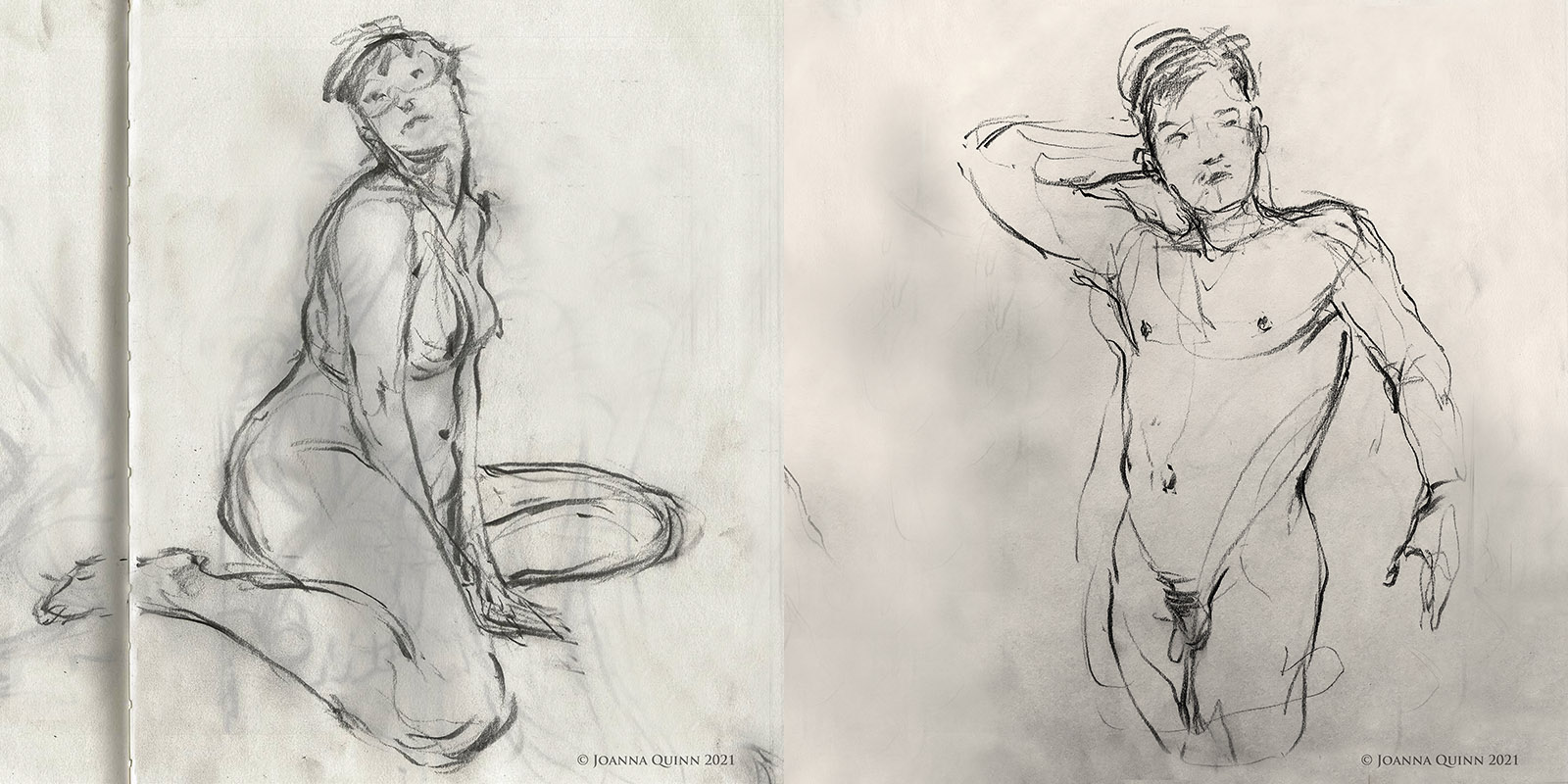

To mark the screening, we caught up with Quinn. She spoke to us about her career path, her and Mills’s creative process, the autobiographical underpinnings of her new film, and the reason she started drawing women instead of men. She has also shared a selection of her artwork and other behind-the-scenes materials from the film …

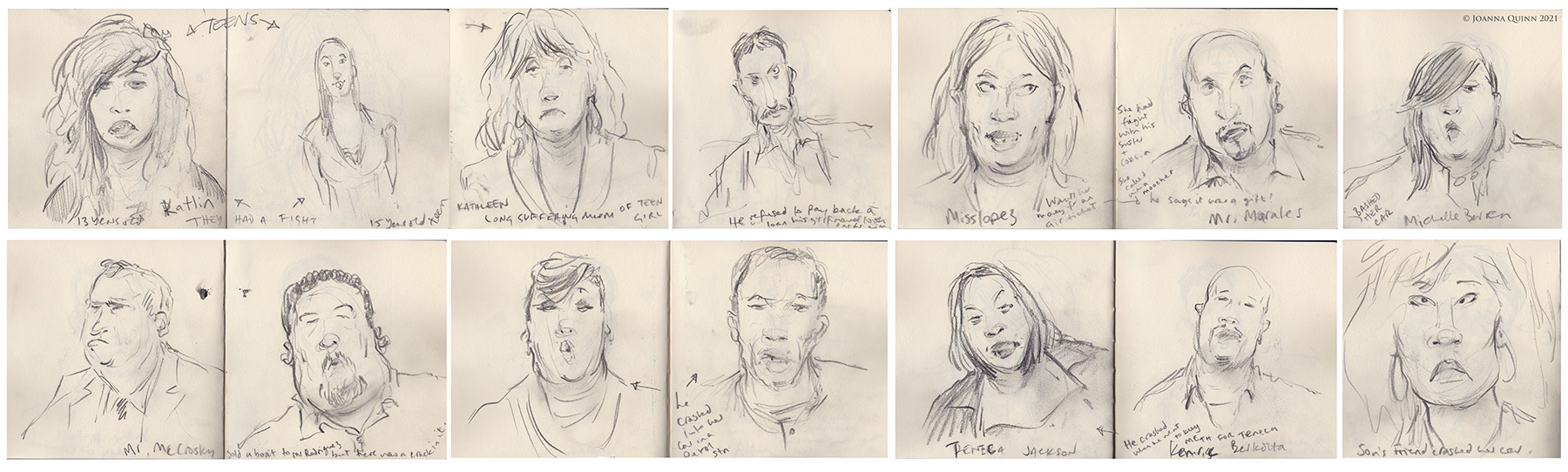

Jen Hurler: Your draftsmanship is honestly on a completely different level. When I spoke with you a few months ago you were watching tv reruns and sketching people on tv shows — do you find that you’re still sketching from the tv?

Joanna Quinn: Well, we have a really old tv in the kitchen and we can only get a few channels, and one of them is 24-hour Judge Judy, so I have become a bit obsessed with drawing all the misfits that wander into her courtroom. This is what lockdown reduces you to. I have also embraced online life drawing, and I just love the fact that the models are often on another continent, posing in their living rooms or kitchens. So yes, trying to keep up my drawing.

Having gone to university for graphic design, had you expected your art career would be less illustration-heavy initially, before you explored animation?

No, not really, as I’ve always been an obsessive drawer, so I chose the course at Middlesex [Polytechnic, now Middlesex University, in the U.K.], which had a strong illustration element to it. Before discovering the wonderful world of animation, I leaned towards illustration and photography. However, I have always struggled a bit with illustration, as I find it hard to do just one drawing — why draw one when 20 would do?

This is why animation sang out to me when I did my first little sequence at the end of my first year. Nevertheless, my graphics training has left its mark on me, as I am partial to a spot of typography every now and again.

Les Mills, of course, is your frequent collaborator, writing and producing the majority of your films, designing the color. He writes about the human condition so well, and it’s shown visually so well. How many drafts of a script would you say he goes through before you put pencil to paper — or is there ever a time like that? Are you storyboarding the film while he’s writing? Do your drawings or pencil tests ever influence the story?

Les writes many drafts of the scripts, and while he is writing I explore the ideas visually in big sketchbooks, which then feed back into the script. So yes, my drawn ideas do influence and change the story. Character profiles, written and drawn, are really important to both of us, and that’s usually where the script ideas begin.

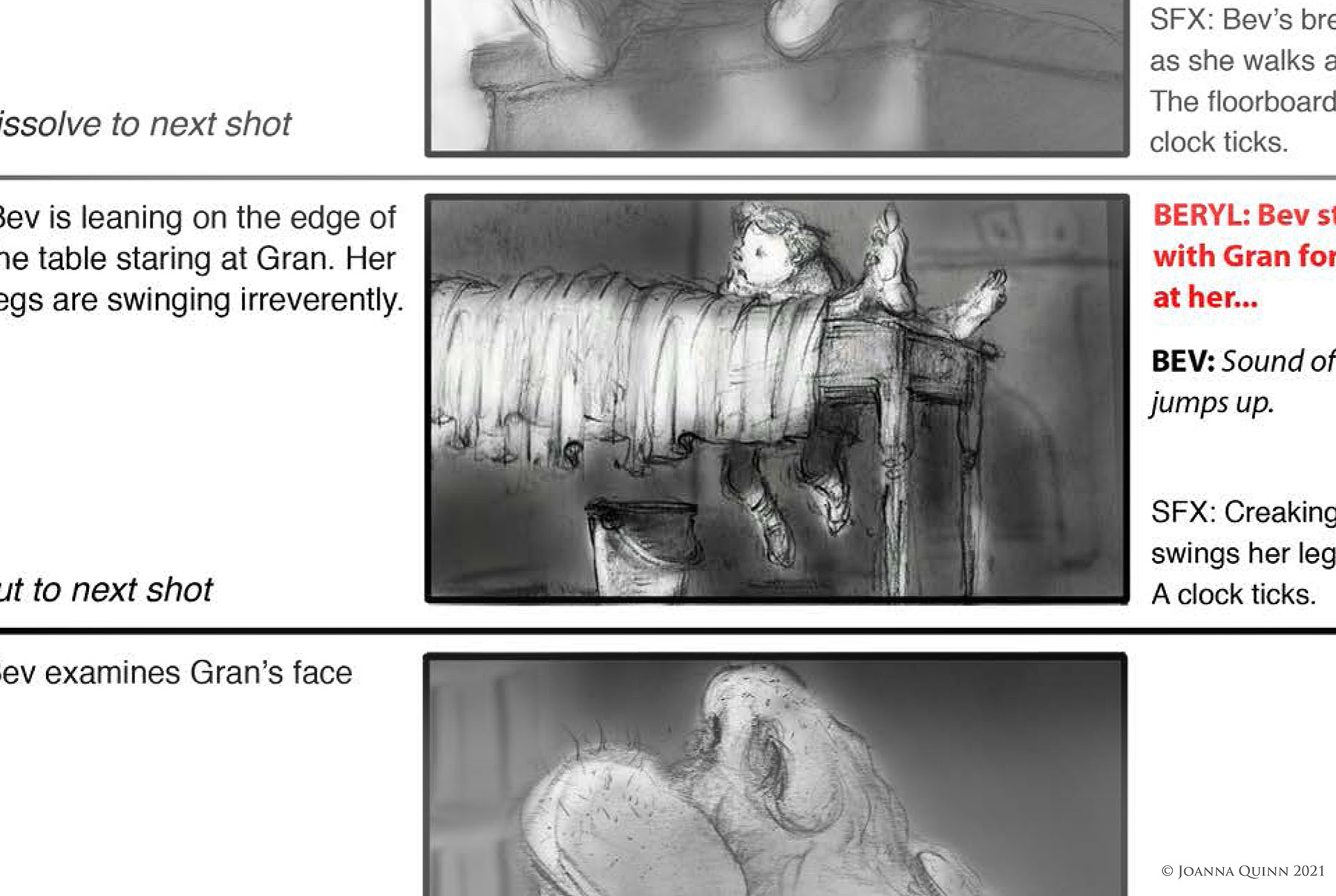

Once I start to do the storyboard, the script morphs into it and the storyboard becomes our blueprint. Our practice when making our films is very fluid, so we do make changes as we go along, making room for experimentation or changes of plan. With commissioned films or commercials, it’s nigh on impossible to veer from the approved script and storyboard because ours is not the final say, but with our short films we can enjoy the actual creative process.

The process involved in making Affairs of the Art has been especially enjoyable because we had a small mixed team of experienced and inexperienced artists. It was like an extended college, and I felt I was learning new things about animation, drawing, and direction all the time. It made me wonder what is most important: the creative process when making a film or the final outcome. I would have said the outcome before this film, but now I think it’s maybe the process.

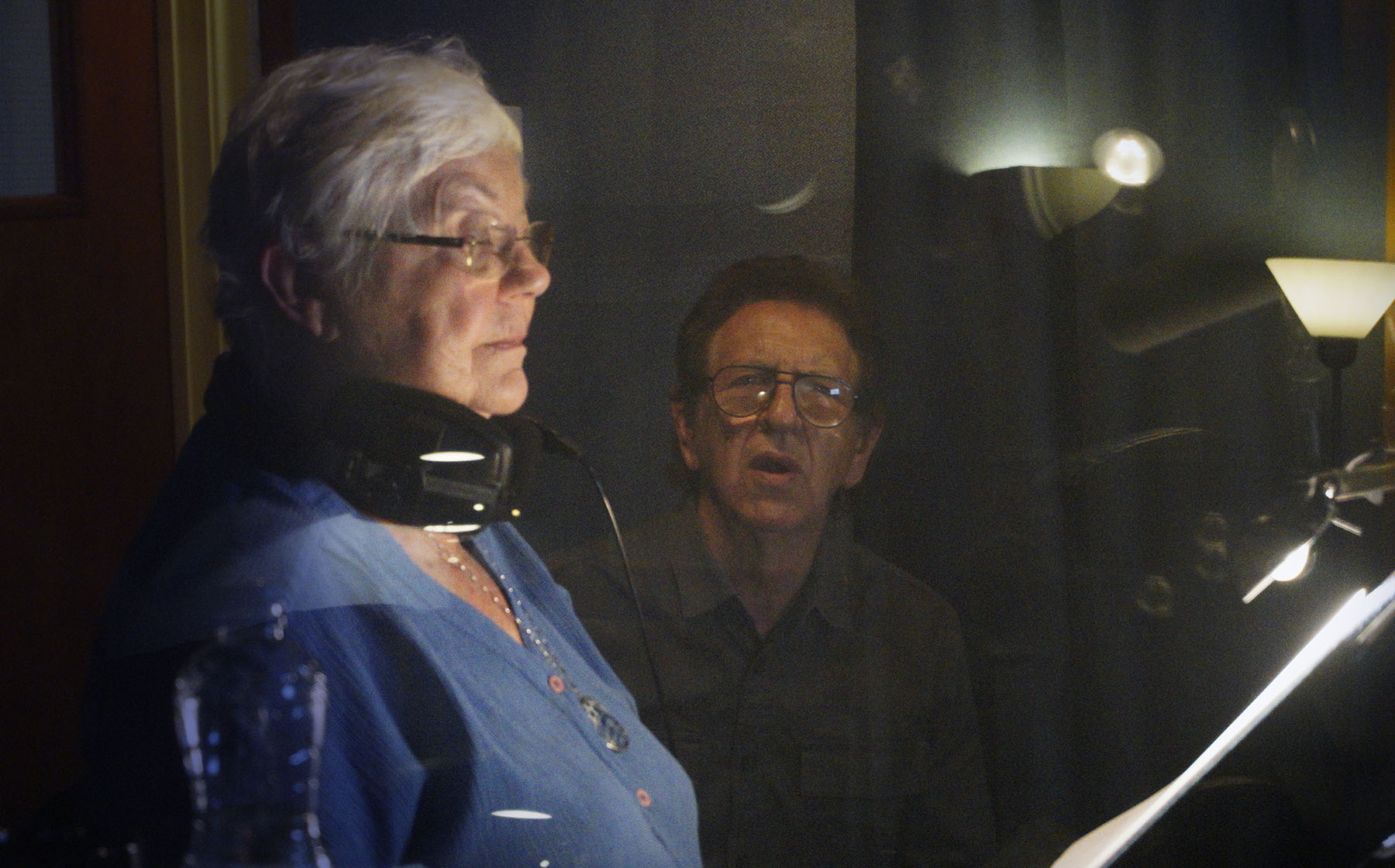

When you have voice actors come in, are you both directing them? Do you leave room for improv or are you fairly locked into the page?

We take it in turns to direct the actors. I remember a couple of times when we have both directed at the same time, but the actors just get very confused and look blank! I think it works best when Les directs them in the booth and I am outside the booth listening to what it sounds like to the picture — more detached. I can then offer advice from afar like “Faster! Faster!” or “More energy!”

It’s surprising how much faster and more energetically the actors have to perform for animation, and you have to keep reminding them. In fact, very often we speed up the voices slightly before we animate, just to add more urgency.

The actors always work from a tight dialogue script, but once we have those lines recorded, we ask them to improvise and maybe ask how they would say the lines if we weren’t there. Without doubt, we get the best stuff that way!

How has your production process changed? Girls Night Out was done using cels, and I read that you bought a Cintiq for this film, but then still went back to paper. So I assume the bulk of this film was tried-and-true paper scanned into the computer? And for scenes with trickier camera moves you used various layers composited together?

Over the years our production process has changed, but it has always been consistently hand-drawn animation. Our first films were done using cels simply because there was no other way of working, but I love it best when I’m just animating on paper with limited color and hardly any backgrounds, like in my films Britannia and Elles.

In Affairs of the Art, it was all drawn on paper, scanned in, then colored in TVPaint and composited in After Effects. I did indeed buy a fancy Cintiq and spent six months animating in TVPaint, only to realize my animation had become wooden and I was quite miserable.

After admitting defeat, I got out my trusty light box and went back to animating directly onto paper. My animation became fluid and I was happy again. Maybe that’s what got me thinking about the importance of enjoying the creative process and choosing a way of working that ignites you.

How do you lay out some of the more complicated camera work in your films? Do you do it all by hand? Do you use multiple layers? I’m guessing you wouldn’t be keen to use something like cg software to do the layout digitally.

There weren’t that many complicated camera moves in Affairs of the Art, but there were a lot in our last film, Dreams and Desires — Family Ties. Those were a bit of a conundrum to work out! Some of the scenes were animated camera moves using reference from footage shot on my phone, and some of the longer scenes — for instance, the pan in the church and Digger the dog going under the tables in the reception — were long layouts all stitched together in After Effects. It was rather mind-melting, but a fun challenge.

We did use some software to create three-dimensional spaces for reference in Affairs, but it wasn’t a great help as it was a bit late in the day. Had we done it earlier it would have been very useful. I have no qualms about using cg software to help solve problems.

Your films are quite feminist, but they don’t necessarily have a “message”: your characters live unapologetically and reflect a particular time and climate. It feels instinctive for you and Les Mills, but I imagine it may have been more daunting in the past when the conversation around such things was less common?

I don’t really remember a time when our films were seen as overtly feminist and unwelcomed. I’ve always had a very positive response from audiences, probably because they make people laugh. It’s hard to be offended when you’re laughing.

When I made my first Beryl film, Girls Night Out, back as a student in the mid-1980s, the climate in the U.K. was much more political than it is now. Margaret Thatcher was in power and there was a lot of unrest around the country.

Feminism was part of that political climate. I was reading feminist literature at the time and started to question my own art practices. I remember when I realized the contradiction of my reading about all these strong women, yet the generic characters I was drawing were always male. Now I recognize the societal unconscious bias to use the male gender as default, but I didn’t at the time.

So I made a conscious decision to draw women, and once I started drawing women, the situations and stories became about women’s lives and seen from a woman’s perspective. It wasn’t a feminist act of defiance — I simply chose to reject the default generic male trap that I had fallen into. I think the same is true of all our films. They are just films from a woman’s perspective, and all the women have strong personalities.

I love that we get to see a bit more of Beryl’s world in Affairs of the Art. What made you pick the specific fixations you did for the characters? Are they based on the hobbies and interests of your own friends and family?

Yes, they are. Both Les and I love to observe, and I have been shouted at in the street for staring at people many times! We normally base our characters and situations on real life. For instance, I got caught drawing my teacher in the nude (the boys made me do it), and I drew all over my bedroom walls.

Les did have a flightless pet pigeon called Percy, and he did used to hoist it up on the washing line so he could be with other birds. The cat next door did kill the pigeon, and Les actually made a crossbow and practised shooting at the wall but missed the cat persistently. Colin is based on Les’s brother, who is a world authority on railway signaling systems, taught himself Dutch, and has written a book on screw threads. Truth is much stranger than fiction!

Kids are kind of weird, and you hit on that so well. The various experiences with pets and injured wild animals are so typical of childhood. A lot of things, too, such as being sad about beet stains fading, are so specific but relatable. Even learning about the concept of death as a kid is of course so universal. I’m guessing a lot of this is pulled from your own childhood?

I think Les and I both had colorful childhoods and got into all sorts of scrapes. As I said before, the young Beryl is very much a mini-me, being obsessed with drawing from a young age. My parents got divorced when I was about seven, and I slipped below their radar. I went a little feral and got into all sorts of trouble, but the one thing I had control over was my drawing, so I got obsessed with it.

Les grew up in the port town of Barry, so his childhood was full of adventures. He did actually see and hear his grandmother die, and was the only person in the room at the time it happened. Also, the laying out of the gran’s body in the living room and the pennies on the eyes are his experience of death growing up, and there was a particular woman in the street who would come and lay out the body whenever there was a death.

The beetroot stain is something that we invented, but Les has always been a bit obsessed with natural dyes, and in the film it signifies her obsession with death and blood.

The end of the film is a little melancholy, with Beryl feeling like she missed out on life. There’s something comforting about Beryl reaching out to Beverly for comfort, knowing that many people would look at a person like Beverly and probably judge her and her lifestyle (for whatever reason), but Beryl sees her sister living her best life.

Well, Beverly has achieved her dreams through determination and ruthlessness. Beryl was never able to do that because she got pregnant at a young age and all her young dreams of going to art school fell by the wayside. Now that she’s older, she looks to Beverly because she is a beacon of hope. She is the embodiment of success. Like Bev says, “Just go for it, Ber, what are you waiting for?” We all need a Beverly in our lives to kick us up the arse.

It feels like we don’t get many shorts that center on middle-aged women. I appreciated that the stakes here weren’t immensely high but were still treated seriously, even with the playfulness of the dialogue and absurdity of the picture (i.e., her slathering herself with paint while calling someone else strange). I appreciate the slice-of-life, almost vignetted episodes.

Luckily, we’ve never had to pitch it! Imagine the scenario: “So there’s this naked, overweight, middle-aged woman who paints herself blue and throws herself on a curtain on the floor.” Next!

I adore the sound design in your films, and it’s interesting how there’s not really a consistent score in Affairs of the Art. I appreciate the silent moments — they make sounds like the pencil on paper so much more satisfying.

We’ve never been fans of constant music in our films. Instead, we prefer to have music at particular moments to evoke specific moods. It needs to be justified and serve a purpose. Also, our films are quite dialogue-heavy, so I think adding constant music into the mix would be sensory overload for the poor audience.

The audio interview in the credits feels a bit tongue-in-cheek (in a good way), and it makes me laugh about how we sometimes have to construct elaborate explanations about our art. I imagine that as you’ve grown into your filmmaking, more of it’s become instinctual and you just go for things, and thus don’t necessarily have a deeper artistic meaning. Also, I’m very aware of that irony as I try to pry into your brain here.

As an artist, I find it impossible to step back and analyze my own films subjectively, especially when I have worked on something for years. I just can’t see the film as a whole when I’ve broken it all down into hundreds of bite-size sequences to work on. When I watch the finished films, I just see all those individual portions fly past my eyes and feel a multitude of emotions — regret, disappointment, pride, frustration. It takes many years before you can look at your own work subjectively and see it as a cohesive entity.

I find teaching very helpful for understanding my own work practices. When I’m commenting on a student’s work, my advice comes from my own experience of animation and filmmaking. I’m put in a position where I have to verbalize my opinions about the process and talk about, for instance, when to punctuate, how to improve the timing, or why the humor isn’t coming across. These are all things that come instinctively to me when I animate, but when I teach I have to consciously articulate the reasoning for my decisions. I love it!

There was a gap between your last original film and this one, with some lovely commercials and projects in between, but the fact that your return to an original film was about an artist discovering herself (and other people diving wholeheartedly into their obsessions) felt quite telling to me.

Affairs of the Art is a bit autobiographical, and I do identify with Beryl wanting to become an artist. As much as I love directing commercials, it is not very creatively fulfilling. It’s fulfilling in other ways: I enjoy the urgency, the constant problem-solving, the orchestrating of a team and the ultimate reward of a happy client. But the creativity most definitely lies with the advertising agency, not with me.

I am beyond happy that this film is finally done and dusted. It took way too long to make, but I thoroughly enjoyed the whole production and was lucky to work with such talented and lovely people. However, I still have dreams of going back to art school and studying the anatomy and drawing the figure all day.

I have to ask the obligatory “What’s next?” here.

We have no plans at the moment, as we are promoting the film with the NFB. It actually takes up a surprising amount of time! We are talking about ideas for another film, but whatever we do, we both agree it will be no longer than a minute and have no backgrounds and limited color. My new mantra is: “Less is more!”

Many people have said how nice it is that Beryl and her weird and wonderful family have brought a bit of joy into our lives during the pandemic. That is great to hear. We fully appreciate the power of humor, and being able to make people laugh is the best gift ever.

Quinn’s answers have been edited for brevity. In the coming months, “Affairs of the Art” will play at Krakow Film Festival, Animafest Zagreb, Annecy Festival, and Anifilm.