Interview: Felix Dufour-Laperrière On His Poetic Hand-Drawn Drama ‘Ville Neuve’

The Canadian animated feature, Ville Neuve, will not challenge Men in Black: International or The Secret Life of Pets 2 at the box office, and that’s perfectly alright. Eschewing the frequently mindless excess, racket, and predictability of mainstream cinema, Montreal-based Felix Dufour-Laperrière’s intimate and poetic hand drawn film (made with 30 people, a budget of $1.6 million Canadian dollars, and using about 80,000 drawings all made via brush and pencils on paper) takes place during the turbulent, anxious times of the 1995 Quebec referendum on independence.

Set in a calm coastal town on Quebec’s Atlantic Coast, Ville Neuve fuses personal and collective destinies through the ruptured lives of a family: Joseph, a bitter hard drinker; Emma, his ex-wife; and his estranged son, Ulysse.

While Ville Neuve is set during a divisive time in Canadian history, the film also reflects today’s increasingly fractured state of affairs.

Cartoon Brew interviewed Felix Dufour-Laperrière via email to discuss the makings and meanings of Ville Neuve. The film screened last week in the Contrechamp Feature Film competition of the Annecy festival.

Cartoon Brew: Ville Neuve is a very quiet film and yet there’s an enormous amount of emotion and tension that is still conveyed. Can you talk about your approach to the sound design/music? Many animators today seem scared to rely upon their images and story and too often seem to drown their film in music and sound/noise.

Felix Dufour-Laperrière: It is indeed a quiet film. I wanted to play with density, both visually and with the soundscape. Ville Neuve tries to put in resonance the intimate and the collective. In order for these echoes to be heard, it needs to have some space and length. Visually, figures and objects are often isolated, taken apart from their context and then established as symbols or signs. It leaves a lot of space for the sound, which is used both for giving context and information and for its own textures, for the sensations it conveys. As the dialogues and monologues are central to the film, the composer (Gabriel Dufour-Laperrière) and the sound designers (Olivier Calvert and Samuel Gagnon-Thibodeau) worked with various intensities, for the words to be audible and to sustain the length of the shots, to link distant spaces and suggest the connections between each character and between the individual desires and the collective ones.

In animation, the reality we represent is never far away from the artificiality of dreams, desires, intimate images we carry within ourselves. I like to establish these spaces as connected, very close to one another. The sound allows to open paths, to overlap these spaces.

How long did you work on this? And how challenging was it to stay focused on such an ambitious project for a long period of time?

Felix Dufour-Laperrière: The first lines of the script were written in 2012 and the film premiered in 2018 (in Venice) and is being released in Quebec and France this spring. It is quite challenging, over this long period of time, to keep our will lively to make a film, but the making of the film was an adventure in itself, an adventure that was shared with a wonderfully devoted team. Making an handmade film, with a pretty restrained budget, working on paper with a light and flexible production structure pushed us to reinvent our tools, to revisit our visual and technical approaches. In the end, it was a great time, yet exhausting.

I’m curious about the origins of the film. Did you have a plan that you wanted to try a feature or did you just have a story in mind that you knew had to be a feature?

Felix Dufour-Laperrière: I was wishing to make a feature, but a feature that would keep a part of the grammar, the independence, and the flexibility of the short form. Animation, in my eyes, is at its best in independent short films, where we can feel that it is invented during its making, that the searching goes on, where we can feel that something is found in the very process of making the images. It allows a real freedom and a very powerful cinematic toolbox.

The story itself was freely adapted from a very short story from the American writer Raymond Carver. I took the general context from his “Chef’s House,” the energies of the characters, and transferred them to Quebec, within a very specific, and tensed, political time.

How much of the film changed over the course of the creation/production?

Felix Dufour-Laperrière: Visually, quite a lot. We’ve had the pleasure of trying various transitions, visual approaches, and rendering of the “reality” of the film. Yet, the final film is very close to the script. Even with the desire to maintain a real freedom and leeway with mise en scene, the script often seems the only object of stability within the turmoil of the production!

As the budget was limited, I’ve done a year-and-a-half of preproduction, drawing all the key poses and preparing all the shots to be given to animators. It gave us a certain latitude in the production itself to readjust some shots, framing, and editing. And to animate some parts with an important part of improvisation.

If the film was in part precisely scripted, it still had certain spots of total liberty. For example, the scene where Emma reads a passage of her book to Joseph wasn’t detailed in the script. The text was, but all the images that emerge from the darkness were created afterwards, with the pleasure of having a moment of pure moving drawings.

What was it specifically that sparked you from the Carver story?

Felix Dufour-Laperrière: I was moved by the two main characters, who convey opposite yet complementary forces. The man is submerged by fatality and anger, but he is still alive and full of desire, an idealist maybe, in a dark way. The woman is lucid yet in resistance. She maintains a challenging sense of hope, without illusions but with a necessary determination. I felt that the situation of this couple gave a light on the Quebec political situation and that it would easily be translated in this different context.

Were you certain there would be no colors in the film? Did that make it even more challenging given the overall quietness of the film?

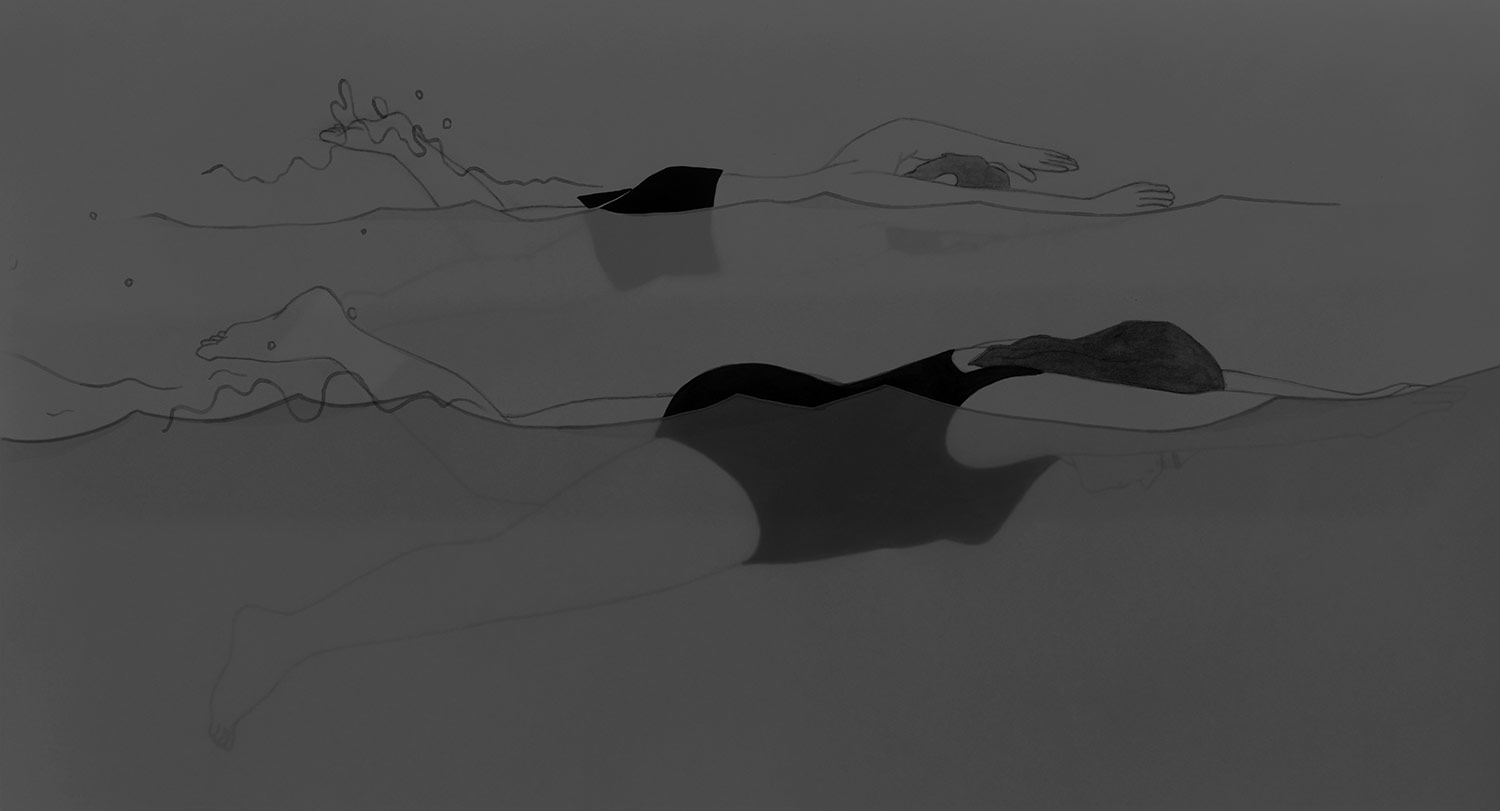

Felix Dufour-Laperrière: The black and white was chosen at the very beginning of the writing — for its graphical quality and for the possibilities of superimposition it allows. The shades of grey permit, maybe more than color or maybe with a greater readability, transparency, blending, and overlapping of images.

It was also a choice of working with ink on paper and to achieve quite simply a specific graphic signature. But the next film (Archipelago, an animated documentary), will be very colorful; I kind of miss vibrant colors and tones.

I loved the scenes where we see the ocean reflected in the cabin window as the couple are talking. It really creates this sense of entrapment, maybe also of hope as well, and just how thin that line is between hope and despair.

Felix Dufour-Laperrière: You totally grasped the intention of these scenes. The sea is at the same time a threshold, an opening and a limit, the end of the land and a space of possibilities, a horizon.

For this scene, the man, woman, and sea were animated on different layers. We’ve mixed them quite simply, dealing with transparency. This is an example where a certain minimalism becomes a strength. The space of the cabin is rendered with only a couple of details, the reflection is a frame within the frame, the white of the paper suggests a depth that we don’t need to detail. It allowed us to easily combine the animated layers.

The background characters (e.g. when Emma and Ulysses have left the cinema) are in stark contrast to the black of the main characters… they’re almost transparent…ghostly… like they don’t matter in the world of these somewhat egocentric protagonists.

Felix Dufour-Laperrière: Collective existence is always partly an abstraction, a combination of elements of various densities and opacities. I wanted the crowd to be at the same time undefined and more than the addition of individuals. The combined transparencies of the bodies build a new whole, that exists by itself but that don’t always interact directly with the protagonists. The crowd then has a graphic existence, its own space and territory, that overlap, superimpose, or is hidden by the main characters. Yet their shades enlighten the protagonists, they draw their attention. And at the end, one of these dark figures, on the top of the church steeple, is revealed to be the son, Ulysse.

I found it quite surprising how much of the complaining by the protagonists is directed at their fellow French Canadians. I guess that my being an English-Canadian, I always thought the dislike/frustration was directed towards the Anglophones.

Felix Dufour-Laperrière: Who loves well, criticizes well, I guess… Seriously, I feel that the question of the independence of Quebec isn’t to be thought with frustration over the Anglos or even the historical inequities of the Canadian federation. It is more a matter of self-determination, of a collective will, of common desires and freedoms. We’ve said no twice to the possibility of our independence, so the responsibilities are ours. As are the consequences and the actual political disappointments.

A lot of that bitterness towards fellow Quebecois comes from the father and son, yet it seems to me that – at least until the bell has rung in the final scene – they are equally guilty of the complacency they accuse others of…

Felix Dufour-Laperrière: Totally, they are definitely a part of what they condemn. It is maybe the origin of their worries, their bitterness. As it is part of a lucid way to conceive politics. We’re always, in various ways, part of the status quo. And it is confronting our desire for change.

Given the events of Brexit, do you think Quebec separation is still possible anymore? Even if the ‘Yes’ win, there seems to be no guarantee that it would lead to a separation (as we are seeing in England right now).

Felix Dufour-Laperrière: The independence option remains relatively strong, with an important popular support. The political vehicles that carry it aren’t, however, in good shape. And they are very divided. A future referendum will certainly not take place in a near future. That said, our collective existence remains to think and organize. To dream. And future political and ecological turmoil will certainly bring to the forefront the issues of the French language, the challenge of living together, the redistribution of wealth, the preservation and occupation of the territory. We will be confronted, as a small nation, with the same challenges as the big ones. With the limited means that are ours. The desires for independence, as much from the gigantic American neighbor as from the actual Canadian federation, could well make a comeback. But as you said, nothing is guaranteed. There is the Brexit on one side, with its confusion. But we can also look toward Scotland, that will probably plan another referendum, on a very different basis then the Brexit. I’m a bit pessimistic but I feel that we’re obliged to maintain the reflection, the will, the difficult hope.