ILM’s Rebel ‘Jurassic Park’ Artists Reflect On The State of VFX Art Today

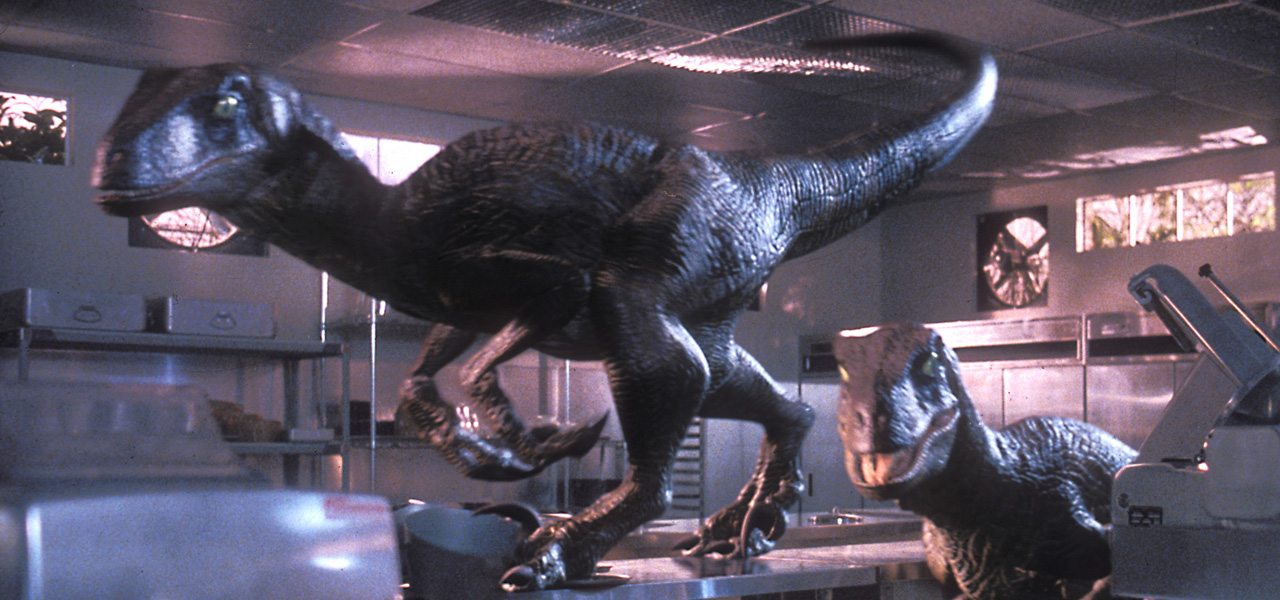

Mark Dippé and Steve ‘Spaz’ Williams famously devised a secret and unsanctioned Jurassic Park animation test at Industrial Light & Magic that ultimately convinced director Steven Spielberg to use computer-generated dinosaurs instead of stop motion on his blockbuster film. It was a huge step forward in visual effects, but Dippé and Williams were no strangers to groundbreaking cg work—they had already contributed to cutting-edge computer animation work in The Abyss and Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

To get this work done, the pair were, and still are, considered mavericks amongst their filmmaking peers because of their approach to the craft and their then day-to-day rebellion against authority. They were even once banned from visiting George Lucas’ Skywalker Ranch after sneaking into the top boss’ private office (intervention from then Lucasfilm exec Scott Ross ensured they didn’t get fired, partly because they were in the middle of delivering key CG scenes for James Cameron’s T2).

Eventually Williams and Dippé left ILM, and have been vocal about the visual effects industry ever since. Cartoon Brew sat down with the duo at the recent Trojan Horse was a Unicorn event in Portugal to revisit those early days and also discuss their views on the current state of the industry.

Cartoon Brew: What was it like at that time in the early-90s at ILM? How did you go about your daily work?

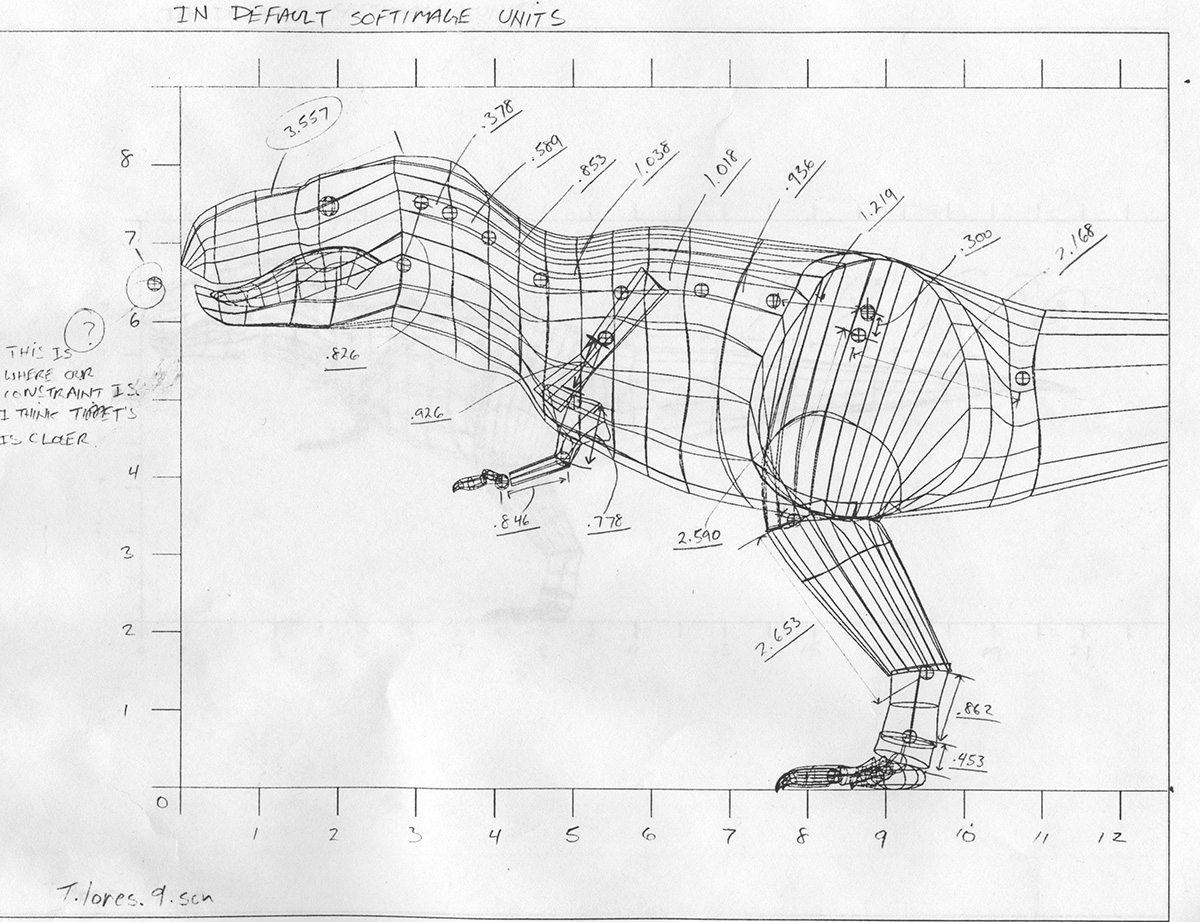

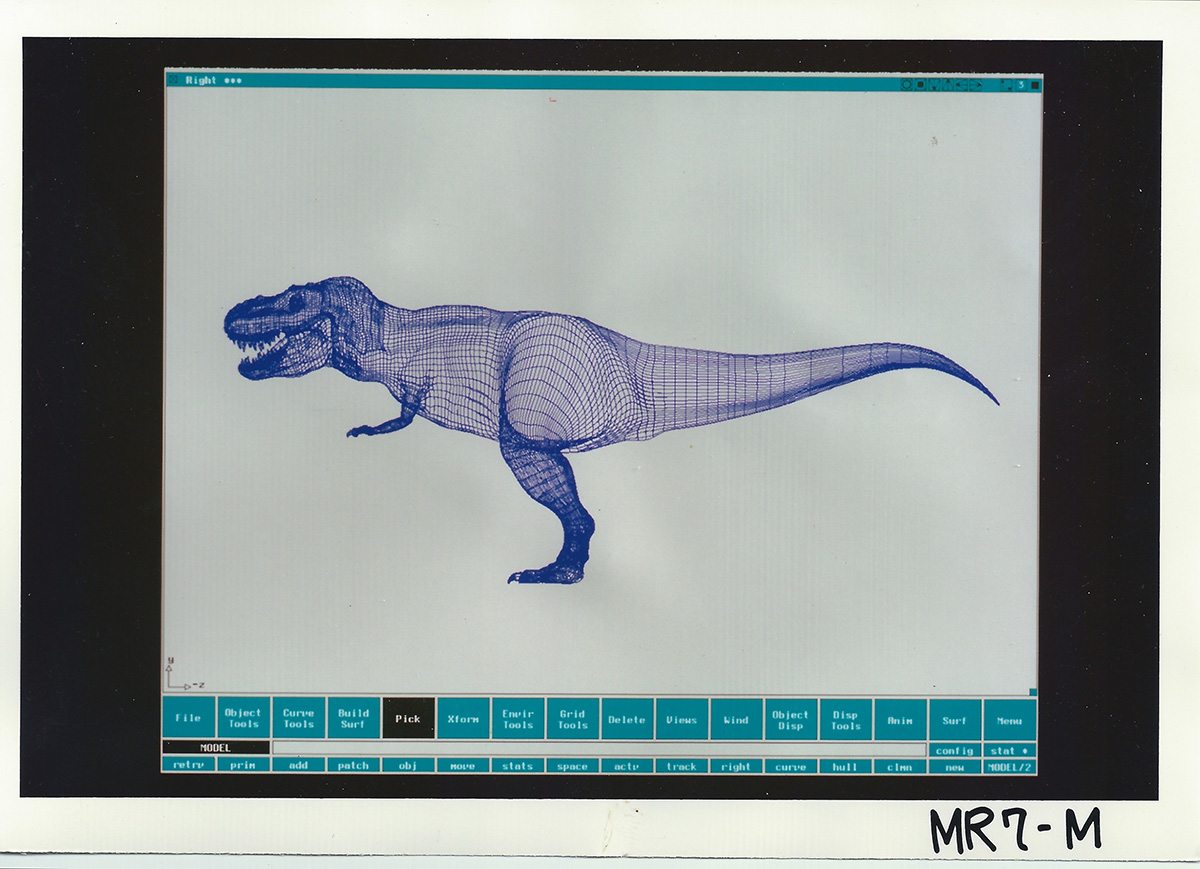

Steve Williams: No one gave us guidance on one thing, not one. We didn’t get any, ‘Why don’t you try this?’ When you got a shot you handled the whole thing with the exception of rendering. So I’d do my own match moves, my own chaining. There wasn’t a separate rigging department; it didn’t exist. So you handled the whole shot, you lived with the shot. Which I always thought was a better methodology as opposed to doing one aspect, then handing it off.

Mark Dippé: In the early days, it was immature. There were no real rules. There was no formal model of how you’re supposed to do it, and so there were a lot of generalists and you kind of did as much as you could, and people learned. As things matured you had these sort of super-technical directors, or generalists, you had people that maybe only animated, people that only did matte paintings, and that evolved. And nowadays it’s more mature and it’s more fragmented—it has more of a pipeline feel. I don’t want to say something like a ‘factory’ as if it’s just machines, but the definition’s clearer. And I think as time goes on it becomes, in terms of visual effects or computer animation, closer to live action filming with different tasks.

Steve Williams: We had a lot of leeway because we were living with the shot and really essentially developing so much. As Mark said, you had to be a generalist and figure out a lot of stuff on your own because there was no one to consult with.

Mark Dippé: It was hard back when we worked at ILM, but nowadays in a lot of ways it’s truly harder, because there’s millions of pieces of data. Literally millions. And no one can conceive of it all or know it all or control it all, and so it’s got all these different methods in which you create it, manipulate it, use it. When you’re building a scene you gotta make sure you have the correct version of a set in there; when you’re animating and someone somehow corrects something you have to get updated, or not, depending on your choice.

What’s your view on the state of the visual effects industry today?

Mark Dippé: The modern vfx-laden film endeavor costs a hundred to two hundred to three hundred million dollars, and it really is such a big business that the entire construction, the entire process, selection of story, development of story, casting – you have a lot of brilliant, talented people involved so I’m not discounting that at all – but it is all directed to the ambition of making a billion dollars worldwide. And that’s a really interesting proposition, an odd proposition.

Steve Williams: In terms of the people, the artists, working in the industry, I think there’s been a big change, too. As all these big films have become more normal, and more standard, unlike what we had done at the time, they needed people who towed the line. They didn’t need rebellion, they didn’t need mavericks, because there has really not been that much of a revolution since then realistically. There’s just been more of what was done to the expense of the storytelling to some degree. We essentially were questioning the big guys all the time, questioning the hierarchy at ILM.

Mark Dippé: And visual effects is not a way to get rich. The business is not an easy business, and one thing about George Lucas, not that we were pals or anything, but bless him for even keeping ILM going because we’d have these little annual things, he would come and give speeches, and I would say that in general there would be some discussion about the economics and it was never a rosy picture. Never.

You both moved into directing (Dippé directed the live action Spawn and Williams directed the animated feature The Wild, and each has directed numerous commercials). Do you think having that kind of generalist approach you mentioned helped?

Steve Williams: The only reason we both learned so much and eventually got into directing was because we’d be on these sets, you know, very advanced sets, watching technically everything go on. So you’re watching how the director acts and you’re watching how they deal with an actor. And then we start directing our own stuff and then commercials. We ended up learning a lot about cameras and everything.

Mark Dippé: In a lot of ways it’s also because you have that desire and you ask for it and you go for it. You know, no one just lets you direct or be the head of the design, you have to have that desire, or you’re so amazing they just say to you, ‘Please do it.’

Steve Williams: I remember when George Lucas wanted me to shoot an additional scene of Boba Fett, for the Star Wars re-releases. He goes, ‘Let Steve direct. We’ll make this, phone this number, here’s where the costume is, find someone who fits the outfit’—he was so matter-of-fact about it. Which kind of blew my mind.

The three big effects films – The Abyss, Terminator 2, and Jurassic Park – that you both were involved with were made more than 20 years ago, but people often talk about how well the digital work holds up. Why do you think that is?

Steve Williams: I just think it’s that the number of shots that are in the film are kinda the right recipe. In the case of Terminator 2, once you’ve got in your head that there’s this chrome character that can change throughout the shot, all of a sudden your brain is writing new stories subconsciously about what this thing is capable of. It’s like, ‘What is he gonna do now? He could fuckin’ do anything!’

Mark Dippé: And then of course we did put a lot of ourselves into it and we worked our asses off like mad. People still do today, but it reflects the desire to make it great. I think another part is, it was so hard to do it. There really were such a small number of shots, so the shots themselves were so important. You could only use them where it was necessary to tell the story, and that kind of economy means that every time you saw it, it becomes more special. It’s not just there for fifty shots in a row.

And another thing we did: our mentor Dennis Muren who really was a believer in what we did and helped support all that, he said that the first time you show off your thing it better be magical because then they’re with you. It’s like they’re cheering in their mind and they’re waiting for the next one and they love it. Nowadays visual effects is just a tool, and so a lot of times it’s used to make a shot that doesn’t work so well have more energy. A lot of times it’s used in a way to cover up weaknesses in storytelling. And it just doesn’t have an impact anymore.

Steve Williams: That was really different when films like Terminator 2 or The Abyss came out. The thing is, people didn’t know what that thing in The Abyss was, and when you saw it, your brain is processing and it’s going, ‘I wanna see when this thing fucks up and makes a mistake, because it’s moving pretty goddamn cool.’

Mark Dippé: Or the audience is kinda going what the hell is that? That’s a tube of water moving around.

Steve Williams:: Yeah, how did they do that? And, hold it, there must be a problem, is there gonna be a wire showing somewhere?

Mark Dippé: The thing I always love to say is—I give James Cameron a lot of credit for this—the water tentacle and the liquid metal man from T2 are the same principle; they are what I would call the classic, perfect digital character. They have all the aesthetic elements that a digital system can be used for and excel at.

.png)