‘How To Train Your Dragon’ Series Director Dean DeBlois On Being Blown Away By The Advancement Of Animation Tech

The technology available at Dreamworks Animation to Dean DeBlois for the 2010 release of How to Train Your Dragon, which DeBlois directed with Chris Sanders, was a far cry from where it is today.

For the latest installment in the film franchise, The Hidden World, DeBlois has taken full advantage of major developments in animation, effects, and rendering tools developed at the studio over the past decade.

As The Hidden World was just starting its worldwide release in early January, Cartoon Brew sat down with DeBlois at Dreamworks Animation’s Glendale campus, where the director reflected on the evolution of the animated filmmaking process over the three films, explained why he likes to get into previs as soon as possible, and discussed how cinematographer Roger Deakins has influenced the series.

Cartoon Brew: How has your process for making these films changed, and how have they stayed the same, over the years?

Dean DeBlois: Some things always stay the same. Like the initial part of the process for me on all three films – it was concentrated on the first film, and it was with Chris Sanders. But there is always a moment where we isolate ourselves from everyone else, and it’s just the two of us, in the case of the first film, or alone on the second and third, where I just work with an outline and kind of hammer that out in the most classic way possible. Just with pads of paper and lots of crumpled sheets in the trash. We’re trying to work out the structure of the story. Then we take that outline and transcribe it into script pages, fleshing it out and really developing character and plot that way. It’s a a lonely and difficult process for me, because it’s full of self loathing and procrastination, and just feeling like a failure.

But eventually you have to turn in something, and that goes through a notes process as well where you get feedback from the studio execs, and from your crew. You pick what makes sense to you and leave aside anything that doesn’t, and continue to shape the story. That part hasn’t changed. We had to do it on an accelerated schedule on the first film just because there wasn’t very much time left, and Chris Sanders and I had been brought in quite late in the game.

Then it gets handed off to storyboard artists, and again that hasn’t changed since I started storyboarding back on Mulan. We sit there with our chunk of the movie, and transcribe it from script to visuals. Now they do it digitally on a tablet, but it’s still the same process. We pitch our work to one another and gather feedback and be as critical as we can. But I think technology has definitely been increasing every year over the decade that we’ve been making these films. Because it used to be that we had to keep restrictions in mind as we were writing and storyboarding. There were just certain things that we couldn’t do, and they involved crowds, they involved organic things like water interaction with solid objects, whether it was a person or a ship or something else.

What are some of the the things you feel you can now mix into the story without any fear of not being able to achieve them technically?

Dean DeBlois: Displacement of clouds for example, or beforehand, we couldn’t have characters walking through grass for example. Our sets always had to be solid rock or something that wouldn’t be displaced. But now, as evidenced in the new film, we can displace sand, we can have snow kicking around, we can move around as much amorphous shapes like cloud and water as we like. We even have characters running through waist-high grass.

Now that we have the technology, I wanted to make sure that we used it. Our environments are very alive. There are a couple of sequences in particular that I really love watching just because the way the crew brought the environment to life, it feels so real. There’s just a gentle breeze moving through the tree branches and rustling the leaves. Wisps of wind cutting through tall grasses or characters are walking through them. Just even the subtle things of having the wind kind of pass and lift up a lock of hair then set it down. It has this sort of secondary credibility to it. That you may be in the moment, and you’re following the characters and the dialogue and that’s what important. Getting the acting and following the story, but on a subliminal level it just feels so much more real.

One of the technology changes seems to be allowing artists to work more interactively via real-time rendering or preview rendering. How has that helped the process?

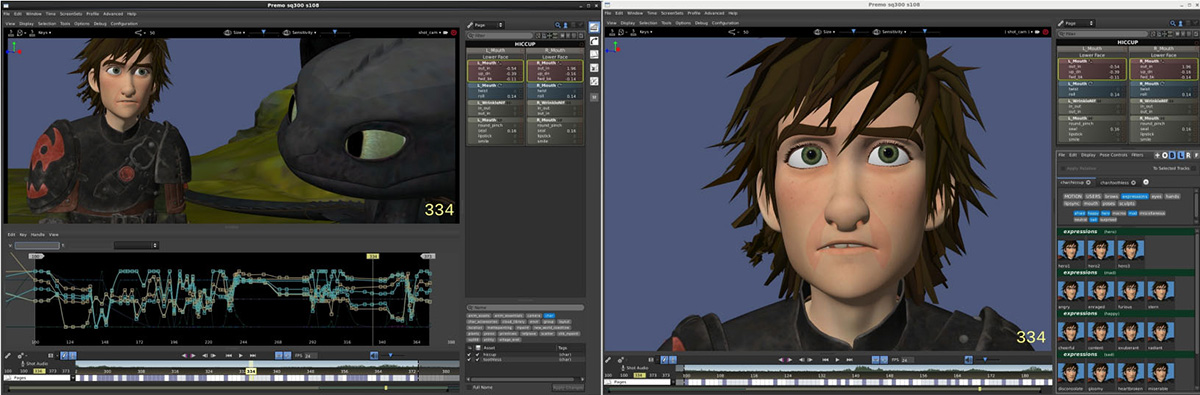

Dean DeBlois: We worked with proprietary software before that actually made it, in a sense, a little difficult for that kind of interaction between departments. But now I think [it’s different] with the introduction of a ray tracing renderer, and with a new pipeline at the backend that fulfills the ambition of the front end. We had some great new tools introduced on this second film that made the animators a little, I shouldn’t just say faster, but a little more adept with the tools, because it was much more interactive in an intuitive way. They could now move around the character with a tablet and a stylus. Grabbing it and pulling it, and creating shapes and pauses.

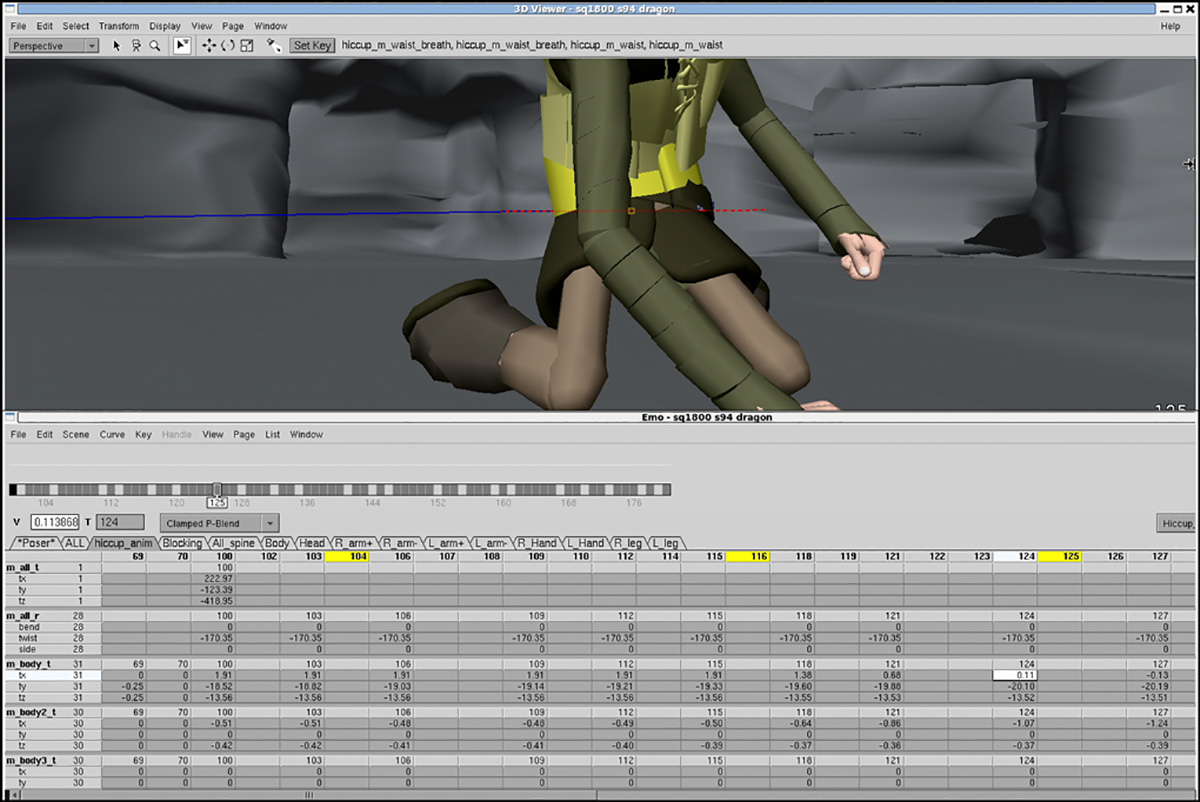

This is the move from Emo to Premo, right?

Dean DeBlois: Yes. It allowed, more importantly, iteration, speedy iteration. We could talk about the shot more often. We could see more versions of it as it got fine tuned. But the biggest problem is that we had bottleneck in our global illumination renderer. It was slowing down our system, so that our grand ambitions for scope and scale were limited by just time. We wouldn’t be able to actually create those frames in time in order to deliver the film. Numbers of characters had to be restricted, and the complexity of sets had to be restricted to some degree as well.

But that kind of went out the window with this film. I never had the meeting that I had become so accustomed to having where the producers would pull me aside and say, ‘Okay, now you’ve got to calm it down a little bit and pick and choose what’s important to you, because we can’t deliver this movie at this scale.’

We could now populate the shots with as many characters as we want, it also freed us up to develop new animation behaviors for our crowd system, to be a little more ambitious with the types of shots. We started doing shots that were – I think they call them compound shots – where we would coordinate or choreograph an action that would normally be broken up into several shots, into one. As the camera moves by, you’re covering the story, and the choreography of characters is handing off from one to another. We’ve never done those shots at the studio before. In fact that’s something that you normally see in Emmanuel Lubezki’s cinematography for The Revenant or something like that. Just very well choreographed live-action shots. They were certainly challenging, won’t say that they weren’t. They required many animators working in concert in order to pull them off. But for the first time in Dreamworks history, we are able to pull them off. It just makes us excited because we can try so many different things that had previously been out of bounds.

In addition to those new tools, has the concept of editorial changed for you over these three films? In some other recent animated features, there seems to be a lot happening in editorial, more than ever before, in terms of shaping the story, and in the way things like storyboarding, previs, and animatics are in the mix. Did that happen on this third film?

Dean DeBlois: It did, and I think the key is exactly what you mentioned. It’s the previs stage between that’s really changed. I think when we were going from storyboards to editorial only, there’s kind of a limitation in terms of, you didn’t quite know how the shots were going to change in a 3d space with camera movement, until you got there. The storyboards were more suggestive and exploratory. Obviously we tried to cover a lot of the acting in animation to get a real sense of how the movie is playing, but there was never really a sense before of how strongly we were committing to the cinematography of it. So, yes, storyboards do go to the editorial department; they do cut together a working version of the story reels. But rather quickly we then move into layout and previs where we can actually realize those shots, and come up with perhaps more engaging or exciting variations of the ideas in the boards.

We can get coverage for shots and try things that might be a little more dynamic, for example, in a flight sequence, where it’s a little harder to indicate what the dynamism of the shot is. More often I’ve seen the previs department and the story department working together. In some cases when we know it’s going to be, say, a dogfight in the air between two characters on their dragons, we might hand off more of that earlier to the previs department. And let them act as sort of an extension of the story department in developing what that sequence would be. Because it’s just much more effective in their hands being that they can move the camera around and play within the actual sets.

In terms of editorial, some people who aren’t in animation, they’re often surprised to hear that there’s even an editor on an animated feature at all. But it must be the case, isn’t it, that editors have a much more crucial role at an early stage.

Dean DeBlois: The big difference, whenever I’m explaining it to somebody who knows nothing about animation, is that I say that, ‘We edit our movie upfront before we ever shoot it.’ We have an editor on early. We build a mock-up of the movie with temporary sound effects and dialogue, and music. If you closed your eyes, it feels like you’re in a cinema watching a movie. You open them, and you’re seeing static images flash at you. But that’s our way of figuring out whether or not the movie works before we open the floodgates of money and start producing the thing.

Just on those aerial scenes and dog-fights, there can be a risk sometimes that previs or being able to place the camera anywhere in such dynamic shots means the audience can get lost in the action, but that didn’t happen here at all. What things were you doing to make sure the audience always knew what was going on in these types of shots?

Dean DeBlois: Well, on the first film we did something that turned out to be of great benefit to us for the entire trilogy. We invited cinematographer Roger Deakins to come spend a day or two with us, primarily to do some workshops to get the lighting department and the layout department kind of working together a little better. In the animation process, layout and lighting can be months, even years, apart from one another. You’re making decisions about camera composition, and camera movement and lens choices, without knowing where your light and shadow is going to fall.

It seemed crazy to me, at the beginning, coming from hand animation where we would always do workbooks. You would get a sense of what the lighting scheme, the shadows were going to be. Coming into cgi animation, both Chris Sanders and I felt very strongly that we needed to build a stronger bond between those two departments by bringing in somebody that we all admire. So, with Roger Deakins, we pitched the movie to him and said, ‘We’d love to get you involved. We knew that you did a couple of workshop days on Wall-E, and that obviously had a great effect on the look of that film.’

Essentially we were pitching him the same idea, but I think maybe he misunderstood. Because he went home and he talked to his wife about it, and then he said, ‘Okay great, I’d love to join the show.’ We realized we might just have Roger Deakins signed for the whole movie!

We talked to our boss, and he OK’d it, and suddenly we had Roger involved from beginning to end. He was weighing in on storyboards, on the shots that were proposed, on the compositions of those shots, whether a shot could be combined into another or replaced by a completely different idea. He was involved in the previs step as well, envisioning camera movement and choices. All the way through to the end where he was involved in consulting on the lighting, sitting down with lighting artists, and talking about color schemes.

Roger Deakins would always question the idea of dynamic camera moves for the sake of dynamic camera moves. He was always saying, ‘Whose point of view is this? Who are we following? Why does this shot embellish that?’ When there might be a natural instinct to wow and dazzle, he would say, ‘You’re distracting the audience from what’s important.’

It really overall made us question choices. Ultimately, the effect was that throughout the three films, we got into this discipline of thinking about character first. We were trying to make a movie that in some ways mimicked the aesthetic of live-action films in terms of its look and its lighting and its sense of peril and consequence. So it made sense to shoot it like a live-action movie. To not try to create shots that would be impossible in a live-action film.

There’s an example of that when Light Fury has been following the vikings and dragons after their exodus from Berk, and she goes in and out of clouds. How did that particular scene evolve, say, from storyboards to previs and into final?

Dean DeBlois: That was storyboarded by Matt Flynn. When we sit down with the storyboard artist and we review their proposed sequence of shots, we’ll sometimes say, ‘Oh, I wish this was a little bit more of an up-shot. What if it was a bit wider? What if we swung the camera around or reveal this character watching in awe?’ These are all discussions that we have when we’re looking at the storyboards. They’ll go back and they’ll do revisions and try those ideas which sometimes work, or sometimes it’s better the way it was in the original version. But that would be all handed off to the editorial department, and they’ll cut a version of it that gives timing to all of those ideas, rough timing. That’s really all they need in the layout department to start working on the previs shots.

For me, I feel like seeing the previs is the proof of concept of the storyboard; it is where the movie really starts to come alive. Because the acting might not be there – we’ve got sort of fairly limited animation, although it gets better every year – but the dynamism of the shots, and where you get that sense of composition, say, how the camera operator is following the action and maybe overcompensating. This is where it really starts to feel alive and visceral to me.

The shots that we choose that come from the previs team replace those, the drawn storyboards, and become a kind of living, breathing story reel. I love to get into previs as soon as possible. I come from storyboarding, and as a storyboard artist, it’s an essential and very creative step in the process. But I think in cgi animation in particular, because you have all of that liberty of movement, you can get to the filmmaking a little faster by involving the previs team earlier in the storytelling of it all.

You mentioned, in terms of some of the newer tools you’re able to use to make these films, that extra detail in the hair really helped with the stoytelling. What is that like as a director to have those tools available to you? What is it like to direct the little tiny details that might not come right from storyboarding, but can be added at the end or even during the animation process?

Dean DeBlois: I’ve discovered something that’s been probably widely recognized for a long time. Your strength as director comes from surrounding yourself with people who are really good at what they do. In the case of the hair, or the flutter of a breeze through clothing, all of those environmental elements that might be blowing and shifting, we have a department called character effects, or CFX, and they handle a lot of that.

I worked with Damon Crowe, who was a head of that department on the first movie, [and] he came back for the third one. I feel like I can communicate the ambition about wanting the environment to feel alive and wanting all of the subtlest movement in places where it’s a quiet dialogue scene between characters, and they take it above and beyond anything that I’ve requested or hoped for. They’ll come back and they’ll say, ‘Look we came up with a way to move a breeze organically through a field of grass,’ in this way that you’ve only ever seen in real life, and I’ll just be blown away.

When I get to see this stuff, I’m just this kid on Christmas morning. Because you never have to walk around and sigh, and say, ‘God, I wish it was better than this.’ You’re constantly blown away and amazed. That’s been my experience all along throughout these three films in this whole decade. I keep being wowed. I’ll often walk out of a meeting thinking to myself, ‘I didn’t realize we could do that, and there it is. Cgi animation, because it’s constantly improving every year, just continues to blow me away.