How the Elves of Aardman and Sony Brought to Life “Arthur Christmas”

With the release last month of the feature film Arthur Christmas, Aardman Animation and Sony Pictures Animation pulled off a memorable new induction into the pantheon of holiday film fare. But pulling off this $100 million dollar computer animated feature proved to be just as difficult — and technical — as the North Pole’s yearly machinations seen in Arthur Christmas to deliver Christmas gifts to kids worldwide.

In Arthur Christmas, delivering presents has become a 21st century enterprise with an army of elves, technological marvels, and a high-tech sleigh for Santa himself. Santa’s two sons Steve and Arthur work to coordinate the logistics while Santa himself delivers presents. The two sons are vying for the mantle of Santa as their father is nearing retirement age, but he isn’t so ready to pass the torch. An unfortunate mishap involving an undelivered toy leads the family in a scramble to determine how to deliver Christmas to one little girl.

Tackling the subject of Christmas for a film such as this can be both heartwarming and harrowing for filmmakers, as they try to get to the heart of the holiday without resorting to clichés.

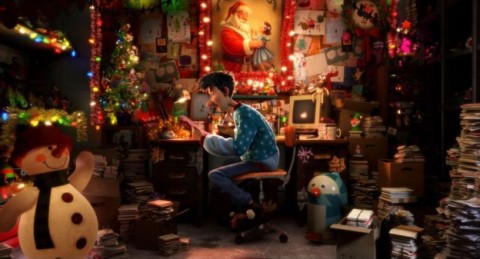

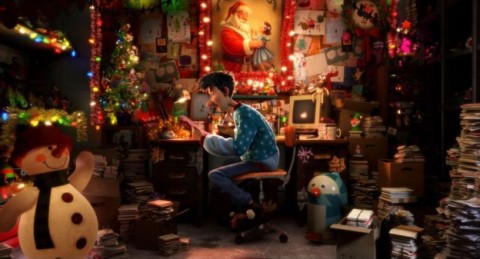

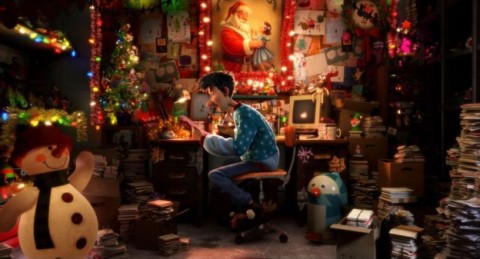

“We didn’t want to set the movie in an entire world of Christmas, but to bring the holiday and its elements into the real world,” said Doug Ikeler, a visual effects supervisor at Sony Pictures Entertainment. “We didn’t want to take viewers to a new world, but rather bring this imaginary place into theirs. Although we knew Arthur Christmas wasn’t going to be clay animated, we wanted it just as tactile as the classic Aardman films with the overwhelming gritty reality of it all. ‘Tactile’ is the word I keep coming back to, bringing that to the scale, the texture and the environment of the film.”

Aardman senior supervising animator Alan Short explained that the key to portraying Christmas properly was developed in the earliest stages of the production.

“It all comes from the script by Peter Baynham and director Sarah Smith,” he said. “It took a contemporary approach to the classic idea of Santa Claus and a band of elves producing and delivering presents to many billions of children. The big question Sarah and Peter asked themselves was, ‘How could it be done?,’ and what they settled upon was a big corporate-type organization running it all, done by an entire family of Clauses.”

Much like the globe-spanning production that is delivering Christmas presents, the production of Arthur Christmas was completed in two stages–first at Aardman’s United Kingdom studio for eighteen months and then transported to Sony’s California studios for another two years of work. It wasn’t merely just handing off the movie to be finished; staff from both studios picked up and moved across the globe to work in tandem in Bristol and Culver City.

“It was scary but really exciting, and probably one of the biggest challenges of my career. Relocating was a big deal,” Alan Short said.

Although Aardman has worked in the past with Sony and other studios on joint productions, Arthur Christmas was the first time they hosted a large contingent of outside staffers and in turn sent a large group of theirs to live and work at another studio.

Aardman has famously had disagreements with previous feature film partners over a cohesive vision for projects, and this partnership with Sony was built on keeping the tell-tale Aardman style and creative control in focus. “I kind of championed the idea to the director that we do as much of the pre-vis work in Bristol as possible,” explained Ikeler. “The original plan was to bring even more Sony people over to Aardman, but the costs skyrocketed that idea out. But we did send staff to Bristol to really understand this collaboration with Aardman and work on a values system for what we were doing and see where their focus was. It was good to go on their ‘home turf,’ so to speak, and see them in their natural habitat. We were, in all senses Aardman employees for a year, and got to see who they were, what they like and how they did their stuff.”

Production designer Evgeni Tomov brought a unique perspective as this project was his first time working with either company. “It’s not the first time I’ve been in the middle of a big business/creative relationship like this,” said Tomov, who worked on the American/French co-production The Tale of Despereaux. “After Aardman’s experience with DreamWorks they were more cautious about how large corporations deal with smaller creative studios like theirs, but they worked through it with Sony.”

Although logistically challenging, bringing Sony’s core team to Bristol and later Aardman’s core team to California was a boon to the relationships, and blending the two studios’ approaches helped the film according to Tomov. “Each studio had its own experiences and qualities, and by bringing them together we were able to use the best of both outfits. Aardman has the creative side and the ability to create unique movies with a specific vision, and Sony on the other hand has the really impressive ability to handle very challenging computer-generated productions and their organization pipeline and production was top-notch. Sony really surprised me with the quality of their work; with the time pressures we had, the results at the end were much better than I expected.”

Taking advantage of the technical prowess Sony had developed, Aardman were able to push beyond the boundaries of their previous films and develop what everyone involved has called their most challenging work yet. “We knew early on how big a movie this would be. The challenge was the scale, the size of the environment, the number of environments, the detail and the number of characters,” Ikeler says. “It was kind of off the charts in all areas in terms of moving parts and complexity.”

One of the most challenging parts became the presentation of one particular item: the gifts. While wrapping presents might be hard enough for the average person, depicting a multi-faceted paper surface with numerous bends and folds is even more challenging for computer animation.

“Wrapping paper is not an easy object to create digitally,” Ikeler said. “Setting up the rig and working with the layers is tricky, and that’s before you hand it off to production. In the end it was up to the animators to figure it out as they were going along.”

That challenge is redoubled in the final scene of the film where the elves are attempting to wrap a kids’ bike while it’s being ridden by Arthur himself. To help understand the process, the animators actually bought a children’s bike and worked through various permutations on how the elves could conceivably wrap a bike while in motion.

“We got a bike and gave it to one of our superstar animators for research,” said Alan Short, the senior supervising animator. “Well, the next time I saw him, he was in the corridor, trying to wrap a child’s bicycle using only three pieces of tape. Later, the supervising animator on that sequence, Alan Hawkins, planned it out meticulously — he could tell you the path the bike takes and how much of the bike is wrapped at any given time.”

Ikeler adds, “We had a little competition amongst the crew — wrap the most exotic thing you can think of. And I’m just saying, if you need to wrap something with three pieces of sticky tape, you can do it. You can absolutely do it.”

At the end of the day, the production of the film mirrored in many ways the production depicted in the film of the Clauses and elves orchestrating Christmas. “We spent so much time on so many things, it’s an absolutely apt comparison,” Short said. “But then, we’re a bit like elves ourselves. We had a great art department and a great animation team. We had a great team that rendered this film so beautifully using the richness of Aardman’s stop-motion work and took it one step beyond.”

.png)