How Shofela Coker Created Beautiful Visuals On A Budget For The Feature Documentary ‘Liyana’

Exalting creative storytelling as a useful method to cope with trauma, filmmaking duo Aaron and Amanda Kopp interviewed and observed a group of orphaned children in Swaziland — an independent nation landlocked in the south of the African continent where the rates of HIV/AIDS infection are alarming — as they worked with performer Gcina Mhlophe in creating a fairytale encompassing their collective aspirations and fears.

That was the emotional core of their hybrid documentary, Liyana, which premiered at the 2017 Los Angeles Film Festival where it took home the prize for Best Documentary Feature.

Within the imaginary narrative the group of kids created, Liyana, a courageous girl, becomes the children’s proxy to navigate the treacherous adventure that incorporates painful events from the young authors’ lives. To portray this fantastical story, the directors brought in Nigerian artist Shofela Coker to craft animated illustrations that are intertwined with talking-head segments throughout the film. Liyana’s animated quest to rescue her kidnapped brothers brims with color and lighthearted charm that counterbalance the harsher realities examined.

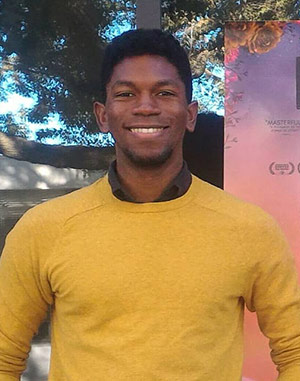

Coker, who’d previously been part of the studio pipeline in both animation and video games, quit his stable job to help the team materialize Liyana as a hybrid production where the live-action footage functions in sync with his visual interpretation of the fictional realm and its characters. His digitally produced images dignify African stories, landscapes, and people, resulting in a vibrant storybook come to life with an uplifting tone in the face of heartbreaking darkness.

Back in 2013, Coker was working for Sony when the Kopps approached him. At that point the directors had already been developing and shooting the project for about four years. They were looking for an artist that shared their sensibilities and could transform the children’s creations into animation. Initially, they presented Coker with a rough storyboard that served as the basis for him to begin production.

“From there, it was basically us working on a proof of concept for about a month, and we developed about 10 shots from that,” Coker told Cartoon Brew in a telephone interview. “Once they got those green lit, I quit my job and I started working on the film full time.”

His decision to essentially go freelance after having worked in a more traditional setting was an easy one to make, he said, because the doc aligned with everything we wanted to explore with his creative process. “As a young artist, it was a very unique chance to develop something that was not just very personal, but also something that I could be proud of.”

His personal connection to the continent where the story unfolds was an equally important factor in his approach. “I’m Nigerian, and one of the main reasons that Aaron and Amanda mentioned for wanting to approach me is because they read an interview online where I talked about the sensibilities that I had about trying to produce a positive image of Africa and Nigeria.”

The Kopps wanted someone who understood the landscape and cared enough to create an authentic African image away from the headlines and Westernized visions of that part of the world. “I feel like a very privileged translator on the film,” said Coker, who notes that although Swaziland and Nigeria are not identical in their visual qualities, they have plenty of similarities. “The color of red earth and the quality of light are very much alike; those are certain things that I have experienced first-hand over there, and I feel really helped me with the project.”

Beyond his own memories of Africa, there was a large amount of reference material Coker had access to from the Kopps’ research and interaction with the children as they told stories, drew, or wrote poems. Coker was asked to reflect that childlike aesthetic.

“One of the mandates was to try and develop the style to look a little bit like it could have come from the mind’s eye of a child, so we took some aesthetic notes from that,” he said. While Coker didn’t get to meet the children during the process of creating the animation, he used the B-roll footage of them playing on the farm, at the river, and being involved in artistic activities as his frame of reference. (Coker finally met them when they were much older upon the movie’s completion and festival run.)

To create Liyana, the heroine at the center of the sequences he crafted, Coker was inspired by a real-life person. During one of his early meetings with the filmmakers in San Diego, California, where he resides, they spent time showing him a rough cut and other materials that could be useful for his task. Among those images, there was a picture of a girl from the farm seen in the doc. Her name is Nosipho, and she appears on screen for a few shot. “She’s sort of the basic model for Liyana,” said Coker. He was so certain Nosipho would embody Liyana in the animation that he immediately got to work.

“Before [Amanda and Aaron] left, I was so excited about the project that I did a rough sculpt of Liyana based on Nosipho in ZBrush, and sent it over to them. The design didn’t change too much from that rough sculpt. I should also mention that all the characters in the film were based on people from the farm, or images of Swazi people that we gathered to give this film a more authentic look,” explained the artist.

Coker’s knowledge and familiarity with the latest digital animation tools matched the cost-effective needs of the documentary. “Some of the sketches were done by hand, but for speed, I [drew on a] Cintiq in Photoshop, so all of the storyboards were redone in about a couple of months, about 400 and something shots in Photoshop, just sketching, and we used ZBrush for the 3d characters.”

For posing, Coker and his team would take the characters back into Maya and developed rigs for all of them to make posing quicker. By doing this, they didn’t have to re-sculpt every single pose in ZBrush. “It just made the pipeline faster, and we rendered out of ZBrush as well.” Backgrounds were created in Photoshop and composited in there with the characters, with effects and movement were added in After Affects.

Coker admits that even if he would have liked to produce hand-drawn animation, the budget limitations didn’t allow for it, so technology became the only option. “For this project in particular, there’s no other way it could have been done. The hand-drawn process would have been too expensive for sure. You work with the best tools that you have. I also believe that you work with the project in mind, and this is what the project called for.”

Since his mandate was never to do full character animation, the characters needed to look more naturalistic, in contrast with more dreamlike and impressionistic backgrounds. The artwork also needed to complement the live-action footage of the charismatic children, and Coker and the directors felt that full character animation might take away from them as the focus.

He describes the animated segments in Liyana as “breathing paintings,” as there is no complex movement, but they are also not entirely static. “The idea was to make every single image look like a beautiful painting that’s just sort of breathing and lifelike.” For reference, Coker looked at old pop-up storybooks, shadow puppetry, and Ben Hibon’s work on Mirror Mirror. “He’s done some animation that looks like paper cut-out work and has a very dreamlike feel to it.”

Liyana deals with harsh social issues from the perspective of a vulnerable group trying to overcome their difficult upbringing and the circumstances they currently face. In that regard, Coker believes animation is a powerful vehicle to address such challenging topics.

“Animation is a very unique language. I’ve seen films in the past like Waltz with Bashir, and maybe more recently The Breadwinner and Loving Vincent, where there’s a very specific vocabulary used in the animation that helps the viewer look at something differently, look at an idea differently, and maybe even look at it, not necessarily from a safe space, but from a space that’s more manageable to process,” he said. “In the past 10 or 15 years, there have been great strides in the breadth and variety of the vocabulary that animation has introduced into the film world. I’m actually looking forward to the future of it, and I hope we’ve done something to push it further. “

Shofela Coker’s work in Liyana is currently nominated at the Cinema Eye Honors, which award nonfiction filmmaking, for Outstanding Achievement in Graphic Design or Animation.

Liyana is distributed in the United States by Abramorama. For more information about cities where the film is screening, go to LiyanaTheMovie.com.