How A New Residency In London Is Trying To Create More Female Directors In Animation

Even as her career as an animator took off, Hannah Lau-Walker felt uneasy. She started out freelancing in London in 2011, quickly amassing experience working on commercials and music videos; later, she moved into directing, earning a Vimeo Staff Pick for her 2018 short Barcelona. Yet as she built up her portfolio, she noticed that few women were doing the same: most animators working alongside her were men.

Frustrated with this imbalance, Lau-Walker resolved last year to make a change. She launched She Drew That, a series of workshops aimed at furthering the careers of female freelancers in animation. They were a hit, but they brought a new problem into focus. Many female animators aspired to be directors, yet that rung of the career ladder was even more crowded with men.

So Lau-Walker went one better and created a residency to help female animators learn directing skills. The inaugural She Drew That residency was held earlier this year in partnership with Strange Beast, an animation production company also based in London (and owned by the Passion Group). Staff and directors from the studio came onboard as mentors.

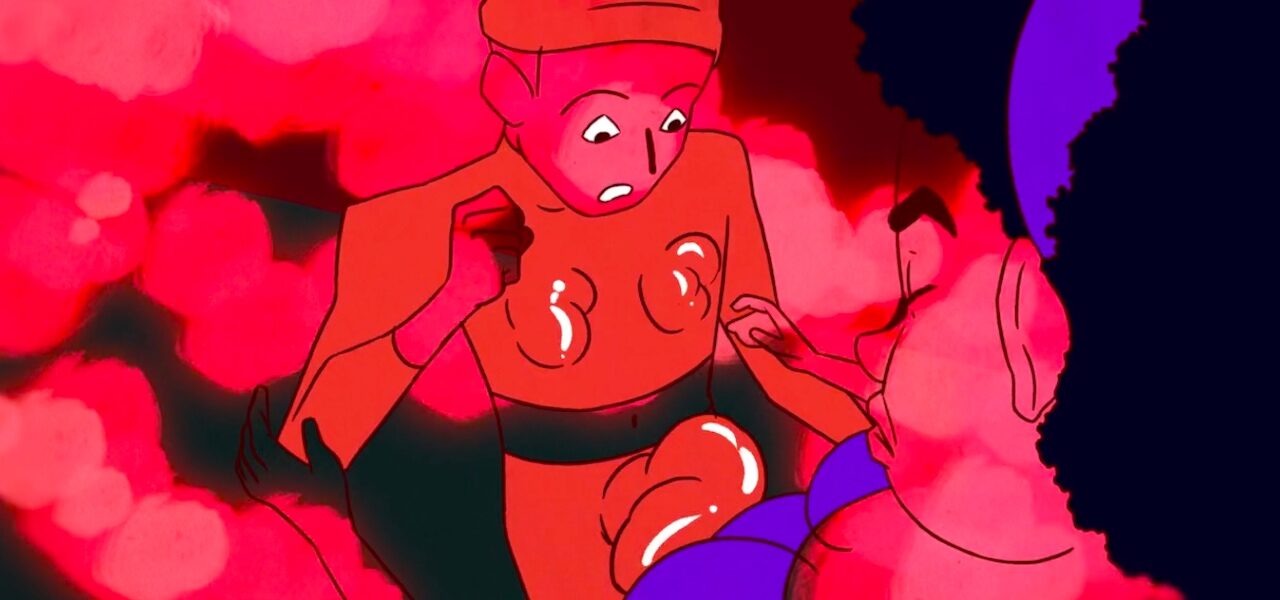

More than 60 women applied to the residency, from which the organizers picked three: Bianca Beneduci Assad, Eva Münnich, and Gaïa Lamiot. Over four weeks, they attended virtual lectures and feedback sessions with Strange Beast’s team, including directors Hannah Jacobs and Anna Ginsburg. The participants were tasked with creating a 15–30-second film around the theme of “Distance” — watch them all below — but the residency was also set up to help them build their professional network.

How do the workshop and residency work — and why does a gender imbalance exist in the first place? Below, Lau-Walker tells us where she thinks the problems lie and what she is doing to help. She is joined by Kitty Turley, executive producer at Strange Beast.

What prompted you to start the She Drew That workshop eighteen months ago, and what did it consist of?

Hannah Lau-Walker: I initially started the workshop after being quite frustrated with the lack of women I was working with. Having been a freelance animator for nearly ten years, I had met very few female animators at the time.

For the first part of my career I was often the only woman in the animation crew, and I just couldn’t figure out why that kept happening. I started seeing more and more women come into animation, which was brilliant, but a lot of them seemed to be getting stuck in clean-up roles. Not that there’s anything wrong with clean-up, but knowing that these women wanted to be animators, I just couldn’t understand why they weren’t getting those roles.

I thought there must be something I could do to help. I realized that when it comes to animation, you can’t get better without practice, and the best practice you can get is on a job. So if women aren’t getting animation jobs, they aren’t going to get better at the same speed as their male counterparts, which means it’s going to be harder to get other jobs. It just felt like a negative cycle. I thought it might be helpful if I could set up practical workshops that had a studio-like structure, where people had deadlines and could get consistent feedback.

The first workshops consisted of a female director giving a talk about their work and process, at the end of which they would give us a style frame. This style frame would then be used by anyone who wanted to take part, as a jumping-off point. Over the month, animators could upload their animations to Slack every Wednesday and get feedback, then at the beginning of the next month we’d present all the animations to the workshop audience and introduce the next director and next style frame.

This set-up allowed women to see and chat with successful female directors, as well as practice their animation skills within a deadline. We found that a few of the women who attended the workshop were even able to get paid work with these directors after the animation challenges. One of these animators has since collaborated with one of the directors on a short film.

The monthly workshops became a combination of positive role models, animation practice, and plenty of feedback within a community focused on professional development and social support.

What then inspired you to start a fully-fledged residency?

Lau-Walker: It was becoming increasingly hard to find new female directors to give talks, especially ones who weren’t just coming out of the Royal College of Art and National Film and Television School [which run the U.K.’s most prominent animation directing courses]. It goes to show how good those institutions are, but I was really frustrated by the limitation of how expensive those places are. It felt like without the financial resources, you weren’t going to be able to develop your skills and have greater opportunities.

Having run the workshop for a year, I felt it was time to go further. I realized that there were a lot of women who attended who wanted to be directors themselves. They had already spent many years developing their animation skills and had really laid the groundwork for being directors. I thought that there must be a way to bridge that gap between animator and director, without spending all that money on an M.A.

Prior to setting up the workshops, I had done two residencies: one in Barcelona, Spain and one in Budapest, Hungary. Having the space and time, away from the hustle of freelancing, really helped me think about where my strengths lay and what I enjoyed creating. My residency was a tranquil space to explore different approaches and come up with a little animation. That animation went on to get me my first commission. So the idea of launching a residency just made sense.

What are the main reasons why female directors continue to be under-represented in animation in London and the U.K.?

Lau-Walker: I think there are two reasons. From the women I’ve spoken to, there are definitely confidence issues. I think there is this resounding feeling that to become a director you have to push your way to the top — to shout about your talent and have a certain amount of certainty about your skills. I think this makes some people feel uncomfortable in that environment, which keeps them out of the spotlight.

But it’s not just about pushing yourself into the spotlight: it’s also about being seen. The animation industry is still a boys’ club, with men running studios and directing animation. They unconsciously engage people they think they can get along with. This unthinking attitude to hiring means that you’ll just be getting the same people coming through. It’s far easier to just give opportunities to people you already know, or a guy that comes highly recommended by all the other guys in the office.

It’s not just the production side — it’s client-facing too: agency creatives have been overwhelmingly male (although that’s fast changing!), and that has, through unconscious bias, created a feedback loop of male directors being selected for projects over female.

Kitty Turley: We have all internalized misogyny. We are socialized to believe that a woman giving direction is “nagging” or being abrasively “bossy.” People are uncomfortable around women with power, so we learn to tiptoe around other people’s egos, and often give direction disguised as an apology. To be a female director in this industry has historically meant feeling okay about making people feel temporarily uncomfortable.

Since we made the decision to make Strange Beast 50:50 gender-balanced (at both director and crew level), I have noticed some wonderful things. Firstly, that there are so many ways to be a leader. I am constantly inspired by seeing directors galvanize a team by giving each individual the space and consideration they need as an artist, by being sensitive and clear with challenging feedback, by showing how work stresses and joys affect them emotionally, and encouraging the crew to do likewise.

And those are all traditionally “female” ways of moving through the world, and, sadly, not often traits associated with directors. I’d also observe that younger directors who joined us once the gender balance was in place are often way more confident in putting their vision across. They’ve come up watching incredible directors lead projects in an atmosphere where gender inequality is a less stark and obvious thing, and in turn they see that there is a place for them in the world, that people want to hear the story they have to tell.

Hannah, how did you devise the residency’s curriculum? Did you do this alone?

Lau-Walker: For the residency curriculum I created a rough outline set around the framework of a real project, from pitch to delivery, which I then sent to Kitty Turley.

Together we developed the curriculum to cover areas that animators might not know about when it comes to a project: how pre-production works, what the pitching process looks like, etc. It was essential to incorporate the studio’s perspective to ensure it was a rounded development program that would lead participants to greater employment opportunities.

How did you come to partner with Strange Beast?

Lau-Walker: I’ve worked with Strange Beast for a while now, and Kitty has always been incredibly supportive of me and all her crew. When I first started the workshops, Kitty and [head of communications] Sam Gray were the first to ask if there was any way they could help. Strange Beast is a studio that currently has a gender-balanced roster of directors, is attuned to the imbalance that prevails across the industry, and has made active efforts to combat it. It felt like the perfect match.

How did you choose the three participants — what were your criteria?

Lau-Walker: The criteria fitted the demands of being a director: women who had over two years’ experience in the industry, and who understood the need to develop their skills and focus their talents to succeed as future directors. Given the number of applicants, we had the opportunity to select women who had diverse experiences and successes. The three we chose were applicants whose achievements and experience really stood out, and who felt like a good match for Strange Beast’s design aesthetic.

We plan on providing more opportunities through a residency, and we feel we have learned a lot from this first one. The main learning has been the ways we can streamline the process: during the conception of the residency, I think I had forgotten how overwhelming it can be to create a film. So I think one thing we will test out in the next residency is separating the lectures from the production of the films, so that the residents can focus on their films after absorbing all the wider learnings from the lectures.