Henry Selick Looks Back On 25 Years Of ‘Nightmare Before Christmas’

Henry Selick’s The Nightmare Before Christmas, his stop-motion collaboration with Tim Burton, is getting a brand new re-release on Blu-ray for its 25th anniversary.

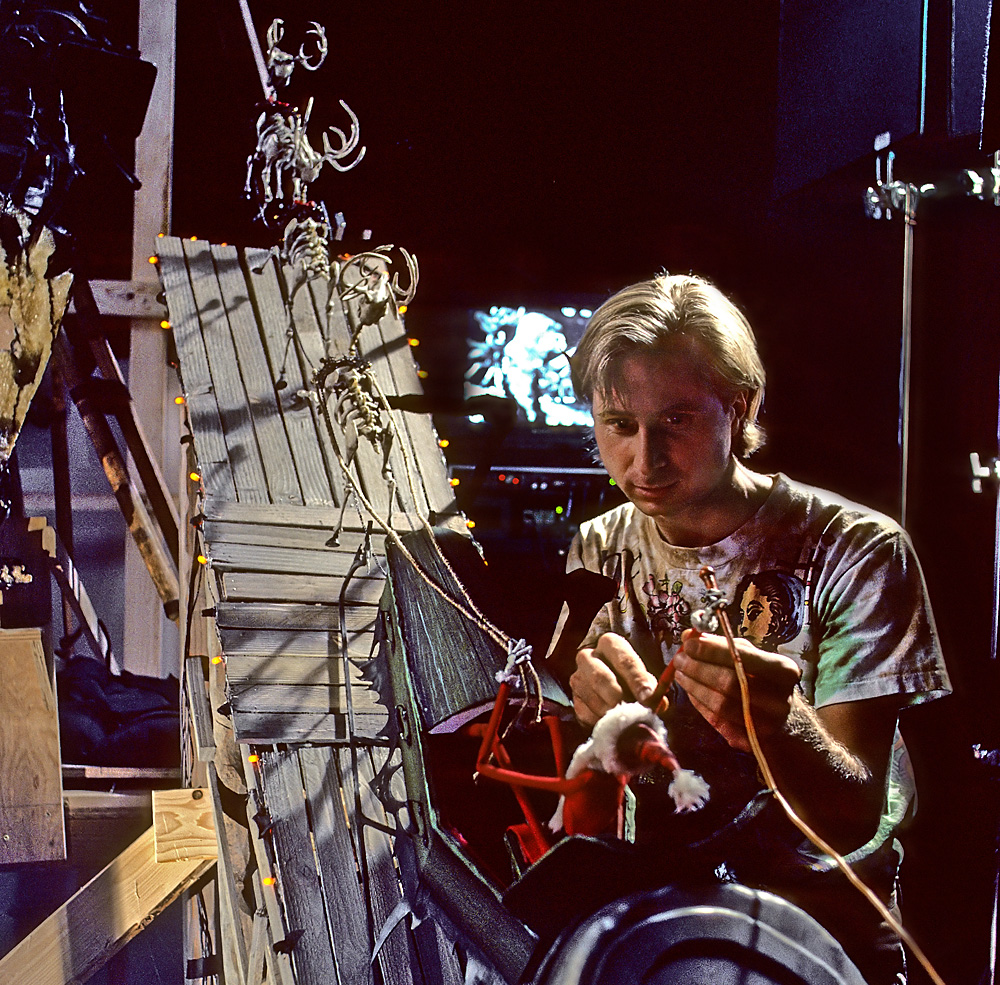

The 1993 film is regularly lauded for its deeply dark, yet comical, story of Halloween Town’s Jack Skellington (voiced by Chris Sarandon). In this unpublished interview from 2015, Selick (pictured on left, in the top image, with Burton) discusses the many challenges that he faced on what was his first directorial gig on a feature, including finding the right balance of horror versus humor, dealing with complex stop-motion puppets, and incorporating – and fighting to keep – songs in the movie.

The Nightmare Before Christmas was conceived by Tim Burton while he was still working at Disney in the animation department in the early 1980’s and before the huge success of films such as Beetlejuice, Batman, and Edward Scissorhands. When the project was revived, “Tim realized he didn’t want to direct Nightmare because the stop-motion would be too slow and painful for him,” said Selick, who had worked with Burton earlier at Disney, “and then he had seen my animation work and thought I would be a good fit.”

Selick quickly gravitated to the story of Jack Skellington, with the director noting he had “a natural affinity for the tone which was scary but fun. And doing it in stop-motion was by far the best medium to carry on with that tone. I think stop-motion is inherently a little creepy, with things moving on their own, but it’s also with the designs of characters being a little cartoony, so it’s almost as if toys come to life, which is also slightly creepy.”

Still, Nightmare couldn’t be too scary. There were adjustments that had to be made so younger audiences were not turned off by the film. “For example,” related Selick, “there’s a scene where Jack’s love interest Sally tires of being holed up with the evil scientists; she wants out. The evil scientist grabs her by the arm and she pulls away until the arm actually tears off. Well, that could have been horrific. But instead of flesh and blood inside her, I had her stuffed with leaves and then as she runs away we see her arm being held by the scientist waving goodbye to her, which ends up being pretty funny.”

Another example Selick outlines is a clown character that has a tear away face. “In an earlier version of that, when we tore his face away, it was a horrible bloody mess. While I realized I might like this, it didn’t fit the tone. So we just made it a black hollow. It’s about pulling punches and winking – death in this world is not really possible.”

With death as a central theme, Selick sought to inject seemingly contrary fun elements into the film, too. “When everyone thinks Jack has died at the beginning, they’re terribly sad, but of course he’s dead to begin with. I had to come up with the term, ‘He’s double dead!’ I think in the end a lot of parents were scared of it, but most kids – even as young as three years old – were nodding their heads along to the songs really having fun. It scared very few children and that was a good feeling.”

Selick did not shy away from injecting complicated crowd scenes in the film or having characters with wonderfully expressive movements – all carried out via replacement animation for the heads and posable steel armatures for bodies. In order to make the ambitious film, Selick assembled a group of collaborators in a studio space in San Francisco – the purpose-built Skellington Productions – which had the added benefit of being away from Hollywood. “I built on this team of animators, set makers, and lighters who I’d been working with on television commercials and MTV spots. I made all those people supervisors and we grew a studio in a couple of old warehouses and basically made the film there. I was there for three-and-a-half years. Tim would come visit and we would send all the footage to him. But it was remarkable, we were utterly left alone to make the movie we made.”

In addition to ramping up physical production on stop-motion puppets, props, and backgrounds, Selick also had to navigate one of the film’s key storytelling devices: song. These were written by composer Danny Elfman, who also voices the singing Jack Skellington. “The truth is, we blindly started making the film with ‘What’s This?’ as the first song and no finished script,” admitted Selick. “That meant the songs were like cornerstones to build the film around. And then screenwriter Caroline Thompson was brought in to fill the spaces of story between the songs.”

“One good thing,” added Selick, “is that when you’re given a song to animate and bring to life, there’s a lot of storytelling already worked out. There was always a story task to accomplish. So getting a song was like being given a running time and a rhythm – it gave us a solid framework to build the sequence to. I ended up really enjoying that. Sometimes it was harder to storyboard and sketch a scene when it was a non-musical part. So, in effect, [with songs] there were limitations in terms of timing and which characters you would go to.”

However, the number of songs in the film quickly ballooned to more than the director thought were necessary. “I complained to Tim that I thought we were going to lose the audience with 10 or 11 songs,” recalled Selick. “He said, ‘Let’s just make them and cut one if we have to.’ When we finished the movie, he said, ‘I think you’re right, there’s too many,’ and I fought like crazy and said, ‘We’re not cutting anything! They’re great!’ For some people initially it was too many songs, but over time they’re such an important part of the movie I couldn’t bear to have lost any of them.” (This week’s new Blu-ray release of the film offers a sing-along mode.)

Perhaps the most complicated stop-motion challenge was the film’s final battle pitching Jack against Oogie Boogie. “Creatively, this was one of the hardest to nail down,” said Selick. “We were sending storyboards to Tim – by fax back then, no internet! He kept rejecting everything and we were right up against the deadline. I realized we finally had to start on the animation. We had some technical challenges too because in that scene it’s like a gambling den and we had these ‘one-armed bandits’ that needed special mechanics. We also had to build a special Jack with a flexible body to dodge some of the weapons used against him.”

In the confrontation, Oogie Boogie’s skin is torn away and revealed to be made of thousands of bugs. Luckily, the filmmakers relied on somewhat of a breakthrough in technology to accomplish complex scenes like the wriggling bugs. “We were shooting on film,” explained Selick, “but we had a video tap on the camera and someone had invented this ‘frame grabber’ device that could grab two images and you could flip a switch between two frames of grabbed image and live image, so you could look at three different things. It was a lifesaver on many occasions.”

“Prior to that,” said Selick, “if you were in the middle of a sequence and a character fell over, you pretty much had to start over or do a cut-away, because you could never line up the character close enough to where he had been before, but with the frame grabbers we could line it up and keep going. That helped particularly with these bugs because you’d have this chart and you could see which direction you had animated, say, bug number 25, so that there was the right sense of rhyme or reason to the overall movement. They were still a real nightmare – I probably have a bag of those Oogie Boogie bugs somewhere in my house.”