From Soviet Oppression To Annecy Success: The Story Of ‘My Favorite War’

Last year, Annecy Festival introduced the Contrechamp program to honor animated features with edge or originality, even by the standards of the festival circuit. Films that would once have been relegated to out-of-competition sidebars now get the limelight they deserve.

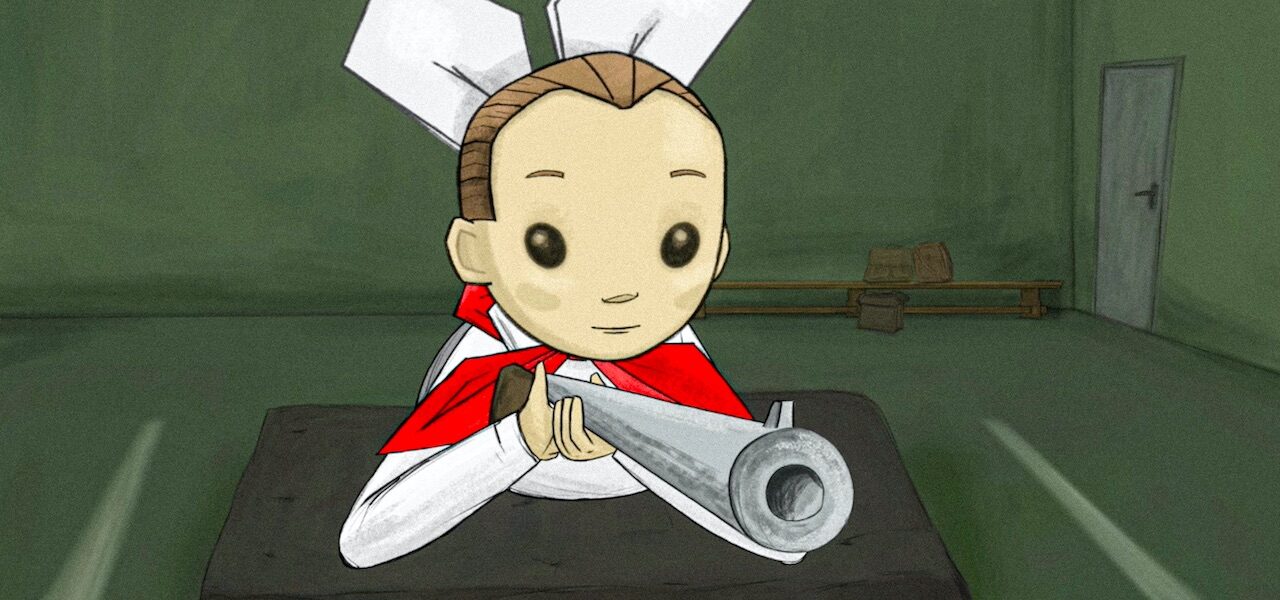

This has worked out well for Ilze Burkovska Jacobsen, whose film My Favorite War took the Contrechamp prize last month, beating stiff competition (including the hotly tipped On-Gaku: Our Sound). Combining animation, live action, and archive images, the film explores the Soviet rule of Latvia with the intimacy of lived experience: Burkovska Jacobsen, who is Latvian, was a teenager when the Soviet Union collapsed.

The director tenderly sketches the tensions in her family, contrasting her father, who ardently served the Communist Party until his premature death, with her mother, who lived with the taint of her own father’s conviction as an “enemy of the state.” The provocative title refers to World War II, whose memory the state regularly invoked to stir up feelings of patriotism; the young Ilze became obsessed with it as a result. Her gradual rejection of state ideology forms the film’s main narrative thread.

My Favorite War joins a burgeoning genre of animated features that present an autobiographical account of conflict and war — I was reminded of Persepolis. What sets it apart is its focus on the experience of this small Baltic country, which has historically stood on the fault line between empires.

The film was made in Latvia, which has a small but fast-growing animation industry, in co-production with Norway. Burkovska Jacobsen, a documentary filmmaker with a background in tv, has worked often in both countries. This project was her most ambitious yet, spanning nine years.

Below, she tells us why it took so long, how she went about reviving this difficult period of history, and what film she watches every year on her birthday…

Cartoon Brew: In the film, we see you as a teenager with a burning ambition to be a journalist. You became a documentary filmmaker. What drew you to cinema?

Burkovska Jacobsen: Partly it was a coincidence. After college I went to Norway, expecting to stay for one year to learn Norwegian. Then the big changes in Latvia started, the Soviet Union broke up, and I decided to study in Norway. Then I realized that my written Norwegian wasn’t good enough to study journalism.

As a teenager, I’d hosted a tv program for young people, so I applied to be a tv director. I became a director instead of a journalist.

You have produced animated/live action hybrid films before, but this is the first time you’ve used animation in a film you directed. Why did you choose this approach? Did you conceive the film in this way from the start?

I knew that animation is the only way to tell this story in the way I want to show it. There are no archives from the Soviet times [showing] the real feelings of suppression. I knew that I had to combine archives, family photos, live footage, and animation.

The animated scenes are stylized, with a cutout aesthetic, yet they are also modeled on very concrete places and events, as we can tell from your archive materials. Was it hard to strike this balance? What directions did you give your team — especially concept artist Svein Nyhus and background artist Laima Puntule — to ensure that you got the effect you wanted?

Both Svein and Laima are very talented artists. They explore possibilities for the best possible expression. Svein was important to this film as an artist who can unite, in one image, childlike visuals with something scary and mysterious.

I came up with a lot of references for props and backgrounds. The visuals had to be true for me. We checked the age references for the car models, lamps in the school, and so on — since I’m claiming that this is documentary. So the images are “documentary-ish,” and at the same time they are also symbols and stylizations.

To what extent did you rely on archive materials, as opposed to your own memory and imagination, to recreate scenes accurately?

The episodes from school, the shop, and other family situations are from my memory. For the school episodes, I asked many friends for help. I created the war episodes from the interviews at the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia. I interviewed several other people on my own too, but only one of these interviews is in the film as a war episode. The script was too comprehensive in the beginning. I had to shorten it a lot.

Did you watch much animation when growing up in the Soviet Union?

I watched what was possible for a kid in the pre-video age. Latvian films were very poetic, often too sad or melancholic for kids, while Russian films were very humorous. On the other hand, I think that these poetic Latvian films have had a huge impact on my generation. There wasn’t much in 1960s, before me; it all started in the 1970s. We grew up as the first generation of Latvians with our own animated films.

But the biggest love and a complete happiness in my life is Yuri Norstein’s Hedgehog in the Fog. If you look at our film’s Facebook page, you’ll see that everyone on the team had to answer the question, “What’s your favorite moment in Hedgehog?” I watch this film once a year, on my birthday. Then it is a happy birthday.

Your grandfather was an artist. What did he teach you about artistic expression?

I remember that I was learning to read and write at the same time around the age of five. At home — I didn’t go to kindergarten. I was writing a play at that time, and I suddenly realized that I didn’t know how to write “G.” I went to Grandfather and he showed me. Then I repeated the letter in my play, writing it always as a block capital. And later I thought that it’s symbolic, because in English “G” is for “Grandfather” and “God.”

This project took nine years. Why so long?

Because I took a long time to write the script. And because it took time to get the financing; I was simultaneously working all the time on other projects to have enough to survive on. I think, in the end, this film needed all this time to become what it is. Last year, I literally used one whole day just to get one sentence right in the voiceover.

How did you go about assembling your animation team? How was the production split between Latvia and Norway?

My Latvian producer Guntis Trekteris from Ego Media found the perfect place to make My Favorite War: Tritone Studio in Riga. They had the right people for the cutout animation and the guts to start this adventure together with me. Svein did the concept designs, sent the drawings from Norway, then they were fitted to animation by artists in Riga. Backgrounds were done by Laima Puntule, who lives in Denmark. A lot of characters were created in Riga by Krisjanis Abols and Harry Grundmann, using Svein’s concepts as a guideline.

Why did you decide to use the English language, not Latvian?

The film is made both in English and in Latvian. But I decided to send the English version for the international audience, because I think it’s easier for the non-Latvian speakers that way. At the same time, I wanted this feeling of authenticity by getting the Latvian actors to speak in English with our Latvian accents. It feels somehow old and real, don’t you think?

Have you had any surprising reactions to the film? I’m especially curious to know how it’s been received by Latvians who are too young to remember the Soviet years.

Not yet. I’m ready to receive all sorts of reactions and criticisms. The premiere in Latvia will be in the beginning of the October. So far, only a few people have seen it, and they react to different things. One journalist said I was too kind to the Soviet occupants. Another said she couldn’t stand the archives of the Baltic Way demonstration of 1989, but during this episode in my film she still cried. Then there was a lady at the test screening who said the film’s mood was too dark. So each person has their own opinion.

One thing was said to me two years ago, when I presented the film as a work in progress at a conference in Oslo. After I screened the episode about my mother’s dilemmas in the communist era, the speaker of the conference said to me: “You reminded me what it is to be a human being.”