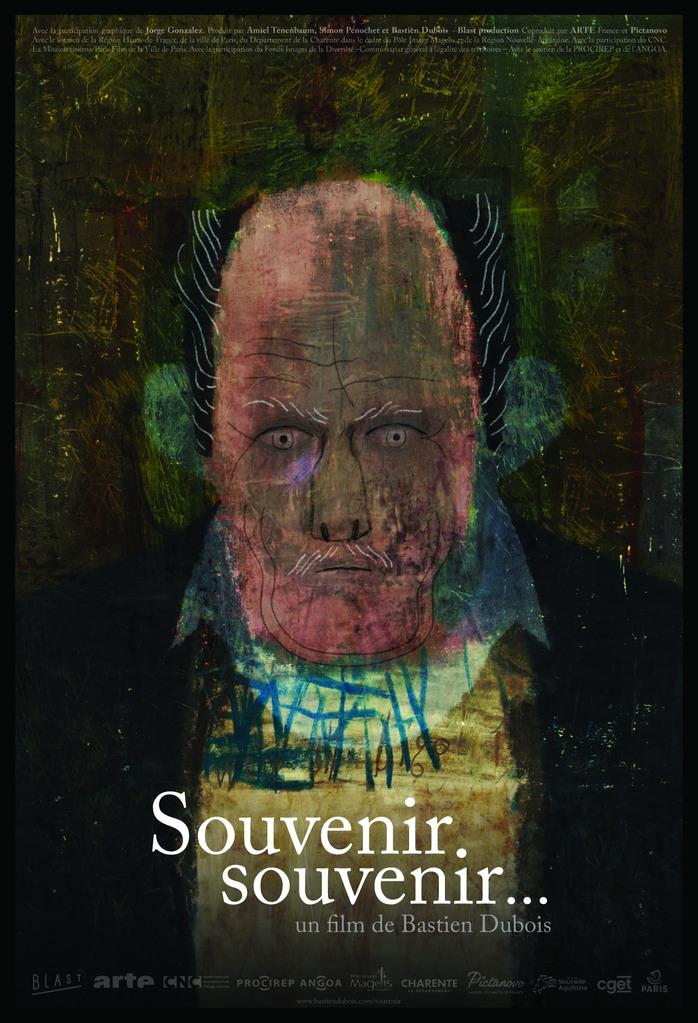

From Family Secrecy To Sundance Success: The Unusual Production Of ‘Souvenir Souvenir’

When festivals are virtual and word of mouth can’t spread as smoothly, it can be tricky to gauge buzz around films. With Souvenir Souvenir, however, there’s no doubt. The new film by Bastien Dubois is on a roll: in the last few weeks, it has been named best animated short at Sundance and Clermont-Ferrand, two blue-chip festivals, and just yesterday, it was nominated for an Annie Award.

The film addresses the brutal Algerian War, an eight-year decolonization struggle that resulted in Algeria’s independence from France in 1962. The conflict will be unfamiliar to many viewers outside those countries; even in France, the events of that time are often veiled by willlful amnesia.

This is, in fact, one subject of Souvenir Souvenir, an autobiographical documentary which follows Dubois’s efforts to understand what his grandfather, a veteran of the war, got up to in Algeria. The grandfather is tight-lipped: he just recites hoary anecdotes about the good times he had with his fellow soldiers. The family gladly embraces this narrative. Dubois slowly realizes that some things are being left unsaid — the “memory” of the title, both personal and collective, is being repressed.

Dubois is at home in documentary. He burst onto the scene with the Oscar-nominated short Madagascar, a Journey Diary (2009), an animated account of his travels in the country, which he later adapted into the travelog series Faces from Places (2013). His second short Cargo Cult (2013), while not exactly a documentary, is a naturalistic study of Papua New Guinea’s experience of colonialism in World War 2.

Souvenir Souvenir, however, didn’t start out as a documentary. Dubois initially set out to create a fictional re-enactment of what he imagined his grandfather might have experienced in the war. He spent years trying to develop the film, changing tack several times. Souvenir Souvenir is about that, too: it is an account of its own creation, the moral dilemmas Dubois faced along the way, and the role of filmmaking in his life.

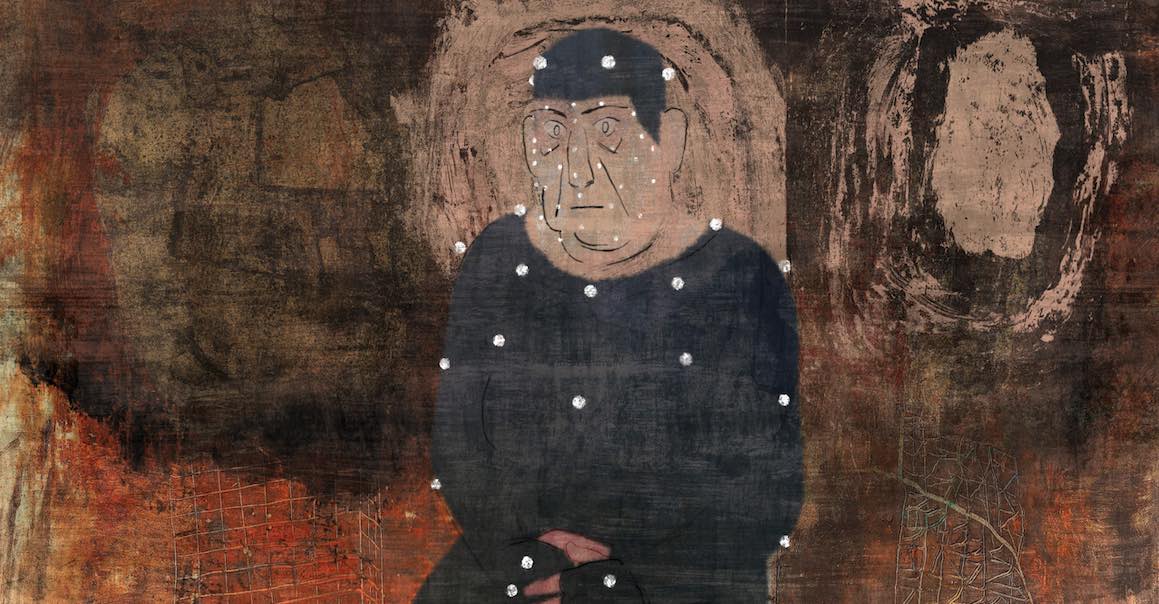

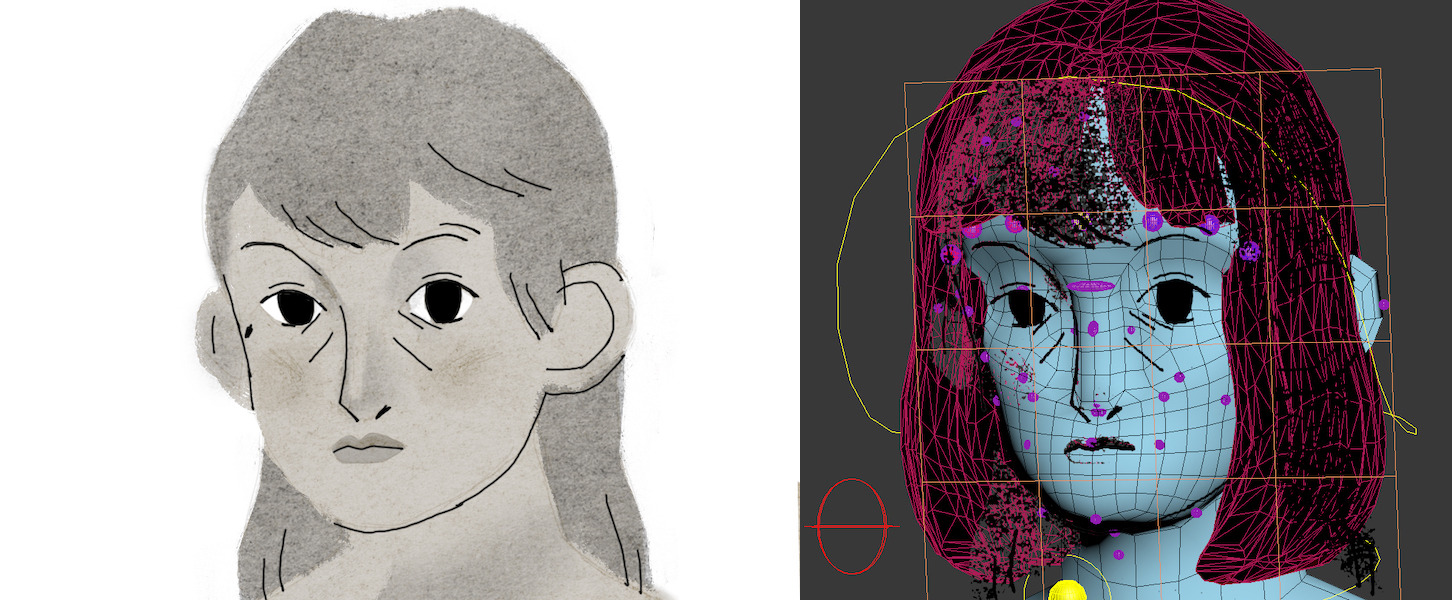

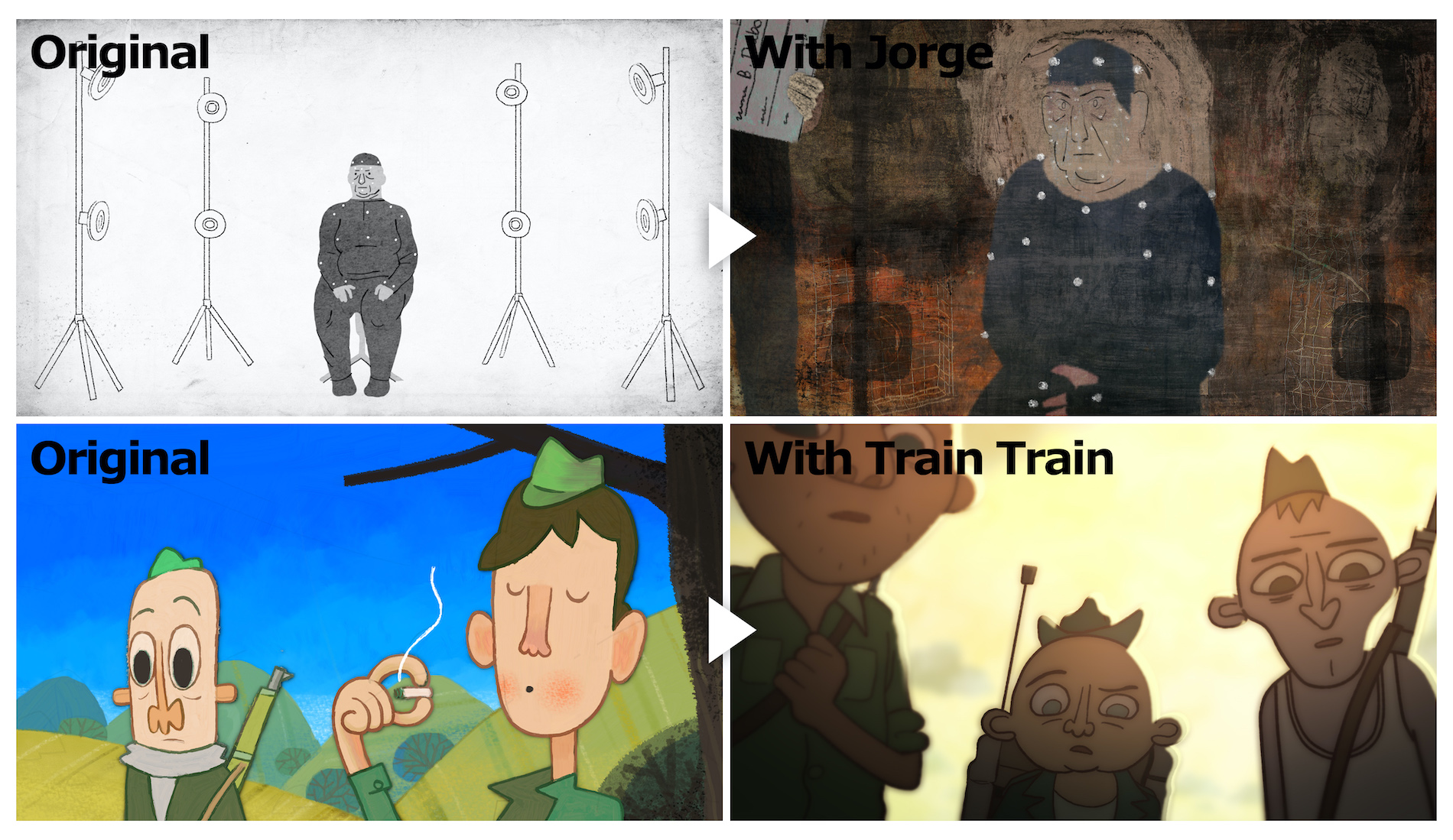

The film combines two distinct graphic approaches. Crude cartoonish scenes represent the earliest version of the film. These were animated by Gilles Cuvelier at Studio Train-Train in Lille, France. The frame narrative, which follows Dubois’s quest for the truth, is rendered in more fragmentary, almost art brut-like segments, animated in 3d but rendered in 2d. The director developed this style with Argentine illustrator Jorge González.

Below, Dubois expands on the unusual development of Souvenir Souvenir, name-checks some of his influences, and tells us how the film went down with his family…

Cartoon Brew: Souvenir Souvenir started out as a reimagining of your grandfather’s time in Algeria. At what point did you decide to place your own relationship with him at the heart of the film? Once you’d decided on this approach, how did the scripting process unfold?

Bastien Dubois: I was thinking about this movie already in 2004–05 — before Madagascar, a Journey Diary. I started with a “cartoony” version. For years, I tried to find others ways to tell this story. I was approached by [film director] Rachid Bouchareb, who I met at the Oscars in 2011, to make a movie for the 50th anniversary of Algerian independence in 2012.

Telling my grandfather’s story was the very first step. But I was facing a wall and I struggled with silence and my own denial for years. I was used to telling people about my attempts: I was pretending to make a movie about that. But when I realized I was part of the problem — that I was in denial too — I had a discussion with a friend or my producer (I can’t quite remember which) who told me: you should talk about your attempts rather than about your grandpa. That’s when it clicked.

And so I started to write it exactly as I was telling the story to people in bars, at the gym, or on public transportation. The whole story of my journey through my denial was already there, in my head, and I was used to narrating it. So the first draft was easy to write.

The first version of the script was written in less than a day. That’s basically the version that was used to get most of the funding and the co-production with [French channel] Arte. Then I was rejected by the CNC [France’s national film board], so I had to re-write. They gave me very powerful, deep feedback, and pushed me to dig deeper. And I think that paid off. It took me a year to re-write. The new version was way more satisfying.

How did you develop the film’s two visual styles? What were the contributions of Jorge González and Gilles Cuvelier’s team?

My first approach was to have a very simple design for this film. Black lines, one layer of gray ink. Almost no background. I wanted to stay away from heavy, complicated, ornamental style I had in my two previous projects, Madagascar and Cargo Cult. I didn’t want the graphic aspect to overcome the story.

But before I returned to my Algerian project for good in 2016, I was working on the development of a feature film with Jorge González and I was very satisfied with what we got. When I paused the feature film for Souvenir Souvenir, I didn’t want to pause the work with Jorge! So we decided to keep going with Jorge for Souvenir. It was also a way to reassure myself: as I wasn’t 100% sure about my script, at least with Jorge I was sure I’d have something strong on the visual side.

I realized Jorge’s own books deal with similar issues: transgenerational trauma, civil wars … The layered, scratchy aspect perfectly matched the topic of my film. In the end, I’m happy we didn’t jump into a feature production with this style, because it was a nightmare to create animation the way I did for Souvenir.

Why was it a nightmare?

Jorge’s style really comes through in the backgrounds and general mood. But the characters are more my own. They aren’t “animated in Jorge’s style,” as that would have meant animating in 2d. My background is in 3d — that’s where I feel more at ease, even for 2d rendering.

So these segments were, in effect, a risky undertaking: I thought I’d prepared several clever tools to make the work easier, but I got caught up in trying to always push it further. That’s the risk when you’re able to do that. Each shot was unique: no reuse, no production pipeline. Real old-school artisanal stuff — I was involved in all the compositing. Nobody could make sense of it but me. So there are many lessons to bear in mind for future productions, especially features…

How close are the more cartoonish sequences to the designs you created for your original film?

See the image below! In the very beginning I was thinking about something more punk and hardcore: I was looking in the direction of Olivia Clavel (a.k.a. Electric Clito) Mattt Konture, Jean Rustin, Mike Diana. I also talked with IMOV Studios [in Brussels, Belgium] about this part of the film.

Then I slowly transitioned to something more cartoony — Dave Cooper, Yvan Duque, Josie Portillo — and then to something definitely more childish like Israel Sanchez. Actually, I wasn’t sure what I really wanted!

The collaboration with Studio Train-Train and especially Gilles Cuvelier pulled me toward a darker, more adult style, which went well with Jorge’s work. I gave them a lot of freedom to deal with the three minutes of cartoonish segments, and that was really restful for me.

Recent years have seen a number of animated films about war and memory, like Waltz with Bashir, Chris the Swiss, or Saigon on Marne, which is also structured as a conversation between the filmmaker and her grandparents. Did you draw inspiration from films similar to yours?

Waltz with Bashir definitely opened the way for films like Souvenir Souvenir or the others you quoted. Madagascar was released almost at the same time as Bashir, and for the next ten years I had offers to direct/co-direct/be an art director on reality-based adult animated features. Always with strong topics.

I thought I was really original with this making-of approach. Later I realized that wasn’t really the case: Adaptation, 8 1/2, Life Without Death, Les Films rêvés … Actually, I feel like I was more inspired by live-action movies than animation. But yeah, Bashir was there also! I don’t know Saigon on Marne yet! Love the title!

Is it easier to draw yourself and your relatives than strangers? Or maybe harder?

Easier to draw myself, funnier to draw others.

How did your family react to the finished film?

No reactions. When I asked why, I realized it was hidden, like we used to be in our family and how we were raised: do not show your emotions.

More generally, has it led to any discussions with people who share your experience? Or with veterans of the war?

I received a lot of messages on Facebook from people who have had the same experience. I also try to screen the film in schools. Getting feedback from teens is priceless. I also had a lot of correspondence with an NGO set up by veterans who decided to give their veterans’ pensions to human rights projects in Algeria. I never tried to get in touch with regular veterans’ associations — I’m a bit scared, I have to admit.

.png)