‘Fox And The Whale”s Robin Joseph On Making A Personal Film: “The Only Way Is To Become Fully Immersed”

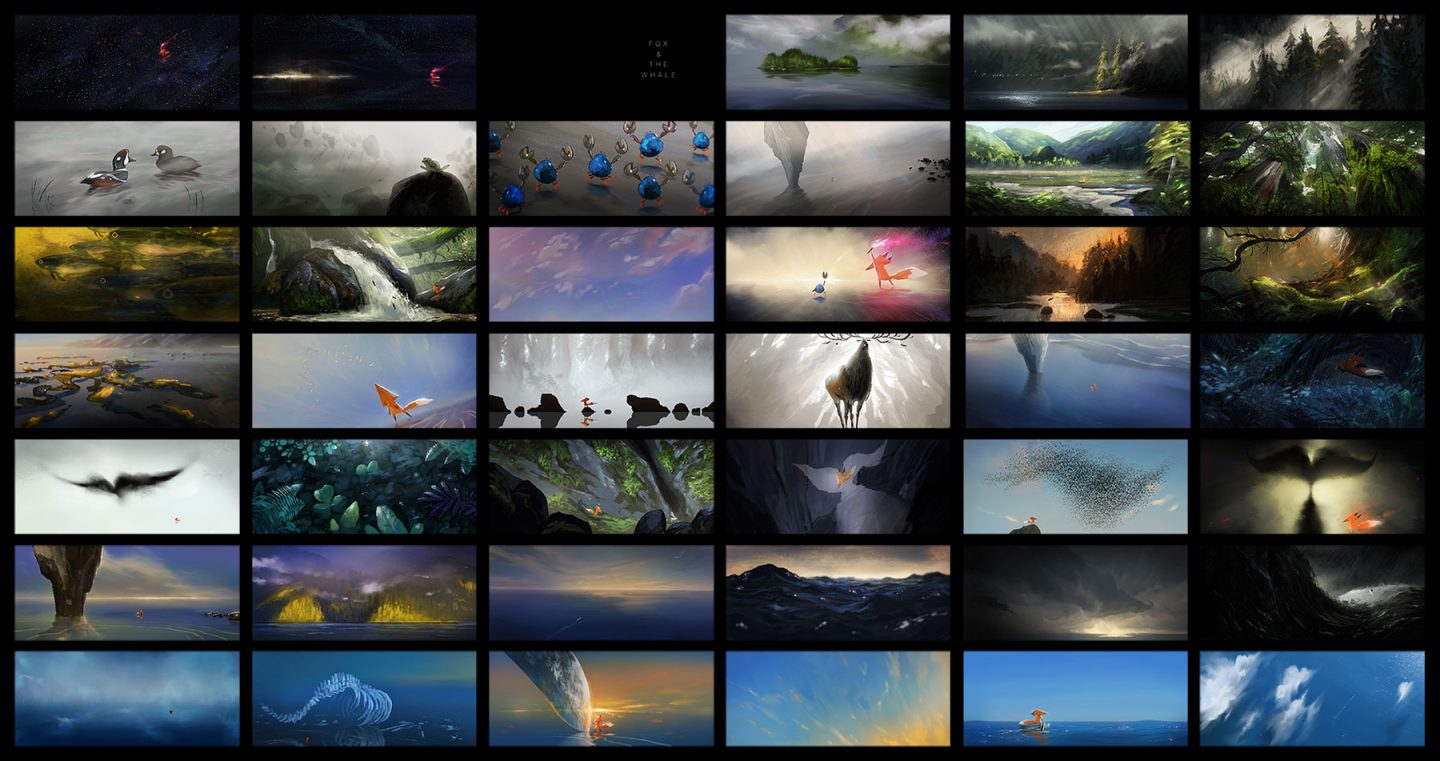

Propelled by curiosity, a lone fox embarks on a journey of self-discovery through a natural utopia. Compelled by the recurring vision of an elusive, mythic whale indicative of a (much) larger world, the fox finds that venturing past the frontiers of the unknown may be the only way to truly know who he is and what he is capable of.

Through that prism, Toronto-based director Robin Joseph’s wordless, wonderful debut, Fox and the Whale, released during our dystopian epoch of exponential global warming, reads like an environmental fable. But the visually stunning 12-minute short’s deliberate ambiguity hides a more personal reading, about a freelance animator with a vision he cannot forget, who is looking to make an impact on an industry that keeps him busy, but distracted from the vision he needs to realize in order to achieve a greater sense of self.

“Fox and the Whale is really an experiment on many different levels,” Joseph told Cartoon Brew by phone, after his sweeping but intimate vision impressively made the cut of 10 short films under Oscar consideration.

That distinction alone may help Joseph really make his name in the animation industry better than his resume, which includes work for features like The Secret Life of Pets, The Lorax, and more. Whatever happens on the Oscars front, the takeaway of his optimistic allegory, Joseph told me, is that following your curiosity and vision where they lead is well worth the time and money, especially if you utterly immerse yourself in the experiment.

Cartoon Brew: Tell me how an animation professional like yourself took time off to make a labor of love.

Robin Joseph: I was working on a few freelance projects, but I always had the idea for Fox and the Whale on the back-burner. When you’re between freelance projects, you never really get to really commit to something like this and see it through. So the only way I could see it coming together was to take time off, and engage with it for awhile. So I started boarding around January 2015, and that went on for three-and-a-half months. Then I spent another month-and-a-half doing color script and tying the design down a bit more before we entered production. By the time final sound was done, it was June 2016, so Fox and the Whale took about 16 months altogether.

You didn’t pause to work on a commercial project?

Robin Joseph: No, I completely took 16 months off. I had to say no to a lot of projects that were coming in. The biggest problem people have working on personal projects in this industry is getting pulled away from them. Getting back into them actually ends up taking more time, so the only way Fox and the Whale could have been finished is to become fully immersed.

How much money did you need to save up?

Robin Joseph: I put up about $40,000 Canadian, and that was just the production. It was probably another $10,000 to $15,000 to take it to festivals and qualifying runs.

You work in an industry undergoing a renaissance, but animated features available to the general population seem to be mostly sequels. Fox and the Whale indicates that those who work within the industry have compelling visions of their own.

Robin Joseph: Of course. The experience I had working on bigger projects really helped with making Fox and the Whale, especially on a technical level, where familiarity with software teaches you to be a bit more nimble. But narratively, I wanted to try something more experimental, which is harder to get in commercial animation, and the only way to really do that was to make it a personal project.

What were the benefits and challenges of working with a small team?

Robin Joseph: Well, production was just my girlfriend, Kim Leow, and I. I was working on Fox and the Whale full-time, and she was working on it part-time. Kim was the character animator, although she had a studio job, so she could only work evenings and weekends on it, or between contracts when she got a couple of weeks off. So we were really the only people on the production that we had to deal with, and there’s a fluidity to production when you’re working within that kind of system. You can eliminate the middleman a lot. Of course, the challenge is that you are the ones doing everything. I had to figure out a lot of things for the first time; boarding and effects were pretty new to me, and sound was very, very new to me.

What did you use to realize your vision, and why?

Robin Joseph: Technically, all the backgrounds and storyboards for Fox and the Whale were done in Photoshop, and all the compositing and visual effects were done in After Effects. With character animation and rigging, everything was done in Maya. On my side everything was done within the Adobe pipeline, because the user interface works well between Photoshop, After Effects, and Premiere. Once you’re kind of comfortable with Photoshop, jumping into After Effects isn’t that much of a leap.

But filmmakers should work with whatever they are comfortable using; anything that helps them solve a problem is the solution they should pursue. I was looking at different suites and much of it came down to cost. Some packages are quite expensive, because of the learning curve.

Fox and the Whale is quite unique in that it is both wordless and patient.

Robin Joseph: Part of it was an experiment to find the limits of viewers who might tune out, because I actually like films that have a gentle pacing. Especially the films of Carroll Ballard, which allow you to ease into their world with the hope that the film will carry you. I think it was a good place to play for a short film, although it might be too straining for a full-length feature. With a 12-minute short, my hope was that I was not asking too much of viewers, that they would give in and come along for the ride.

How about the short film’s majestic setting, which seems based on Salt Spring Island in Canada?

Robin Joseph: The inspiration was from a trip I took back there in 2008. I had never seen anything like it before, and it left a really strong impression on me. A year before I made Fox and the Whale, I also drove around California, including Muir Woods, which really stayed with me too. That said, the geography of Fox and the Whale is not specific to a particular area, although it is inspired by the Pacific rainforest belt.

These areas are under severe environmental stress. Did that inspire your film’s poignant sense of loss?

Robin Joseph: Narratively, the film is not directed at climate change or the environment in general, although the locations were impactful. From a purely narrative perspective, the world the Fox leaves behind is a rich, lush, safe environment, but it is also what drives him out into the bigger, wider world. I wasn’t thinking too much in terms of an environmental message, although Fox and the Whale has come out at a time where that is a strong conversation piece, but it wasn’t so much the impetus for the film.

What was the impetus? What is the Fox chasing after in the Whale?

Robin Joseph: Part of it is the loss that you talked about, as well as a sense of failure or disappointment. But the larger narrative point of the film is curiosity, and its pursuit. Much of my inspiration came from science and exploration, especially space exploration, because there is no guarantee of success, or even an indication of what success may be. It isn’t a framed answer. My hope is that people who watch Fox and the Whale come away with a sense of optimism, that in spite of loss they still want to move forward. The pursuit is worthwhile. That’s the key thing.

And here I thought your film was cli-fi, while it leans more toward sci-fi.

Robin Joseph: Many of its sequences were inspired by photographs from the Hubble Space Telescope, but again that’s a personal thing. I don’t think someone needs to watch Fox and the Whale and specifically connect the dots to space exploration, because its narrative core is really curiosity. In some way, it’s an allegory trying to achieve the quality of fable. But as long as the audience leaves with a sense of optimism, that’s great.

Were you specifically referencing Melville’s Moby-Dick, which explores similar themes, among so many more?

Robin Joseph: Not really, although I’ve had a few people ask me that. Years ago, when I created much of the original artwork for the film, that name just really stuck with me. And I suppose whales kind of carry that weight of something much larger than life, to the point that they’re almost abstractions. Fox and the Whale is not specifically about one whale, or one kind of whale. In general, cetaceans are an example of something so much larger than yourself, which contrasted well with the Fox.

Intentionality is only part of reception; once your vision is out, so are its interpretations.

Robin Joseph: Yeah, Fox and the Whale definitely has a level of ambiguity. I’ve had people interpret it in many different ways, and that’s fair. It’s left a little open-ended, so you can claim it, and attach your own interpretation to it. I don’t think any of that is necessarily wrong.

Like your Fox, has your experience of departing from your industry work to commit to your vision left you with optimism about making more of an impact on the industry?

Robin Joseph: I saw a wall in the direction that I was going. One of the reasons I got into animation was to make films, and there weren’t really many opportunities to do that in the way I was working. One thing about the animation industry is that if you work in one area long enough, you kind of get labeled for it. I started out as a character designer, and so I was eventually labeled as a character designer, and it took awhile to shake that away and do something else. Whenever I get labeled, it scares me. It was getting to a point that I didn’t see an opportunity where someone was actually going to ask me to make a film. And being a freelancer, you’re not really tied to studios, so that is eventually what presented me the opportunity. I had saved up enough over time, and it was a short window where I thought it was worth a shot.

The other part of it is technical. Because I work on large productions, features and commercial projects, with hundreds or thousands of people, I can only contribute so much, and only have so much of a voice. But with Fox and the Whale, from end to end I could really try and discover whether it would be a success or failure. So technically, I was trying to see what it takes to do that. How many people does it take to make a short film with a high visual bar? I’m discovering if my next film can scale up in scope. Fox and the Whale is really an experiment on many different levels.

.png)