Faith, Nazis, And The Queen Of Scratch: A Conversation With Andreas Hykade

The Bavarian town of Altötting, which lies midway between the birthplaces of Adolf Hitler and Pope Benedict XVI, is known to Catholics as one of the holiest sites in Europe. For centuries, pilgrims have been coming to venerate its famed statue of the Virgin Mary and offer votive paintings that depict them in her presence.

In the world of animation, the town has another claim to fame: it is where renegade filmmaker Andreas Hykade was born and raised. The experience and effects of a conservative Christian upbringing resounded through his first three shorts, the so-called Country Trilogy: We Lived in Grass (1995), Ring of Fire (2000), and The Runt (2005).

Hykade’s filmmaking then took a turn for the abstract: as he refined his graphic style, he broadened his range of subjects. Love & Theft (2010), an homage to his artistic inspirations, riffs deliriously on the iconography of cartoons, while Nuggets (2015) offers a minimalist study in addiction — or is it spiritual angst?

Even in these films, autobiography was always present, but it returns to the surface in the director’s new short Altötting. As the title suggests, we are in his hometown: the film opens with the young Hykade’s religious epiphany — infatuation, even — before Mary, then tracks the progress and decline of his faith. As he tells us below, it took him five years to make the film, but three decades to prepare for it.

Altötting was made in different circumstances from Hykade’s previous works. It is his first film since he became the director of the animation program at the respected Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg. As well as his usual German producer Studio Film Bilder, it was co-produced by the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) and Ciclope Filmes — an arrangement the director describes as “a most beautiful experience.” Regina Pessoa, a renowned filmmaker in her own right, worked on the film as artistic director, painting supervisor, and co-designer.

Ahead of its premiere at Annecy Festival’s online edition, we called Hykade to discuss the film. We spoke about the beauty of religion, the downsides of virtual festivals, the hazards of “poisoned work,” and the “Queen of Scratch” …

Cartoon Brew: Altötting moved me, which almost surprised me, because the film relates to an experience I’ve never had — I wasn’t in contact with religion in my youth.

Andreas Hykade: I don’t agree with you. A couple of people have seen the film, and the ones who aren’t connected with religion can’t emotionally connect with the film.

Did you expect that would be the case when you set out to make the film?

That’s not the way I’m thinking. I try to be patient enough for all the elements I need to craft a work to come together. Usually you have to wait for 20 years. I always want a personal layer to be in there, so I can give proof of authenticity. There also has to be a collective connection, to ensure that there’ll be an interest for the audience. There are also a couple of other layers connected with craftsmanship: finding the tools you need to craft the work in a certain medium.

Although I’m alienated from religion, it was clear to me that I cannot destroy the beauty of religion, which has to be transformed into the secular world. First it took me about 30 years to get from a devoted religious person into a secular person. Then it took me another five years to get the distance to be able to speak about it, without discrediting the Holy Spook that lies within.

Was it easy to return to those feelings you had in your youth?

Yes. That’s what we humans are: we carry around this baggage of experience. The difficult thing was to find a narrative that suited the purpose, where you could show the different elements struggling within the subject.

Another thing that I had to focus on achieving was the silence. I came to realize that silence is probably the most essential part of the whole craftsmanship. First you have to get yourself in the [appropriate] mental position. The other thing was to get everybody in line with that, because the usual way of craftsmanship is being faster than the audience.

But my work is rooted in making a connection with the audience, first by abstraction — leaving space — then by getting the audience into a position where they can reflect on the space that’s delivered. The silence is the key to making that relationship work. I’m not just talking about audio silence, but visual silence as well. We can see it in the early work of Adam Elliot. He was limited: he couldn’t move the bloody camera, so he created space for us to reflect.

Tell me about the paintings in the shrine. They were made by pilgrims depicting themselves in the presence of the Virgin Mary.

They were in the style of the time. They were simple paintings. You’re a farmer, you fall under a tractor, you survive. You buy a piece of wood, you paint yourself under the tractor with the Virgin Mary. Or you get someone else to do the painting. You make up a little rhyme. You note the date and the place, and you put that thing up in the church.

When I was visiting the chapel, up until my mid-thirties, there were still paintings from the Nazi period. Soldiers with swastikas praying to the Virgin Mary. I was always particularly interested in these. They were always so politically incorrect, but in this little village nobody ever [cared]. It gave it a certain authenticity that you couldn’t find anywhere around. Now, they’ve replaced them with some bright and shiny, awful stuff by ten-year-old pupils who have no connection with the Virgin Mary at all!

Were you interested in these paintings as artistic expressions?

No, I was interested in them as my door into my own virtual reality. This was before the internet — I’d never heard of Picasso. Imagine a place where you’re alienated from all the art you see. So you’ve got to take what’s there. And [the art in the chapel] was the most attractive thing that was there.

Did you ever paint yourself with the Virgin Mary?

No. I drew all the time, but other stuff. I was just an imitator. I drew the Flintstones, Daffy Duck, Batman. The concept of introducing myself into my own art began [when I discovered] Robert Crumb’s The Many Faces of R. Crumb.

Altötting reminds me of films you made earlier in your career, that were overtly autobiographical. It strikes me as especially similar to Ring of Fire. Mary looks like the incarnation of beauty in that film. And the themes: inexperience, infatuation, lust. Was Altötting conceived as a prequel to that film?

Yes, I thought about it in those terms. Beside the subject of religion, I had to make connections between all the other stuff lying about. I wanted to be consistent. I want the film to be shown at this show called My Funeral. It should not be bits and pieces — it should be related.

For the past 25 years, I’ve tried to open up the range [of my filmmaking]. After Ring of Fire, I did a children’s series, Tom and the Slice of Bread with Strawberry Jam and Honey. It was like consciously leaving a path. I don’t want to end up as a one-trick pony. Even if it means losing your audience: I feel like I lose my audience every time I make a bloody film. Every time, I go in the opposite direction [to the last one].

With Altötting, I thought, “If I now go in the opposite direction again, it becomes a trick! So why not combine all the bloody stuff — why not do nothing new?” There’s probably only two and a half seconds in the film that are new. These two and a half seconds will be the door to the next project.

Which two and a half seconds is it?

The Nazi. Hitler was born 20 kilometers from Altötting, and 20 kilometers was where Pope Benedict XVI was born. That was the cultural range.

You’ve spoken in the past about a project you called your “Jesus film.” What is the status of this project?

I’ve got the story. I’ve got a brilliant ending — because it’s so hard to find a good ending, that’s both completely natural and utterly surprising. The [project’s] invisible world is already developed. The visual world … we don’t know. I have different options.

The little bird in my film Nuggets was good for me, because I could draw him in three seconds. But this Jesus thing, it’s tricky, because you have one guy running about with many others following. That’s a problem in terms of animation! But I’ve got the script. It will be a long format: 26 chapters, all about two minutes along.

At the moment of loss of faith in Altötting, you say in the voiceover, “She left me.” Why not “I left her”?

Why do you ask that question?

I haven’t had this experience, but my assumption is that it would be a choice that you make.

You’re getting to the heart of the thing now, because for four and a half years the sentence was “And then I left her.” It was the one crucial thing that I changed in the end. I had 24 different versions of that sentence lying around. Another one was “And then I killed her.” It’s interesting you point that out — I’ve got to credit you for that!

I’ll have [a sticking point] in every film. I’m German, so I plot things out. I usually don’t produce a frame that I don’t need. But there’s always this one bone you bite on. I changed that sentence. Why? In the end, it doesn’t matter who left whom. What matters is it’s the end of a love story. So it becomes a question of taste, almost. “I left her” would not [express], convincingly enough, the moment of isolation.

To change that sentence is the difference between autobiography and fiction. In my autobiography, [I would have written,] “I went to this office, and I said I don’t want to be part of the Catholic community anymore.” So the sentence “I left her” would have been right. But the hurt, Alex. We’ve all left people, and we’ve all been left behind. The hurt is bigger when you’ve been left behind.

You’re sensitive to the choice of music in your films. Altötting features Schubert’s “Ave Maria,” which is obviously appropriate for the subject. But how does the song make you feel?

It’s beautiful. It’s an allegory. It goes through the good times and the bad. I always imagined it as a woman’s voice, because it’s so beautiful. But the musician [who arranged the music for the film], Daniel Scott, wrote me an email one day and said, “What about changing it to a male voice?” I thought that was good: it’s like an echo that haunts him, like he’s singing it to himself. So I went for that option.

You narrate the English version of the film, but as this is an NFB co-production, there’s also a French version. How does it feel to hear another actor [Normand D’Amour] narrate such a personal story?

I don’t speak any French, but I was [at the recording session]. Do you speak French?

Yes.

What do you think of his version?

His delivery is slightly more tempered than yours. It sounds like he’s narrating with more emotional distance.

My producer Marc Bertrand is [a French native speaker], so he directed it. I knew one thing — especially with French — it should not be over-emotional, especially with an emotional subject. Otherwise, it becomes kitsch. The English version is the original for me. Not the German one, for which I also did the voice. Not the French. That’s a political statement, because I think this bastard language is the language of the future.

How did Regina Pessoa become involved with the film?

If I believed in God, I’d say she became involved because she had to. But as I don’t anymore, I can elaborate. In 2000, I finished Ring of Fire. It was a scratchy film, but the scratchy [style] was stiff, in a way. In the same year, Regina had her debut with the film The Night, a scratchy thing as well. A beautiful film, fueled by the spirit of Eastern European animation, of Piotr Dumała, but transferred into her own.

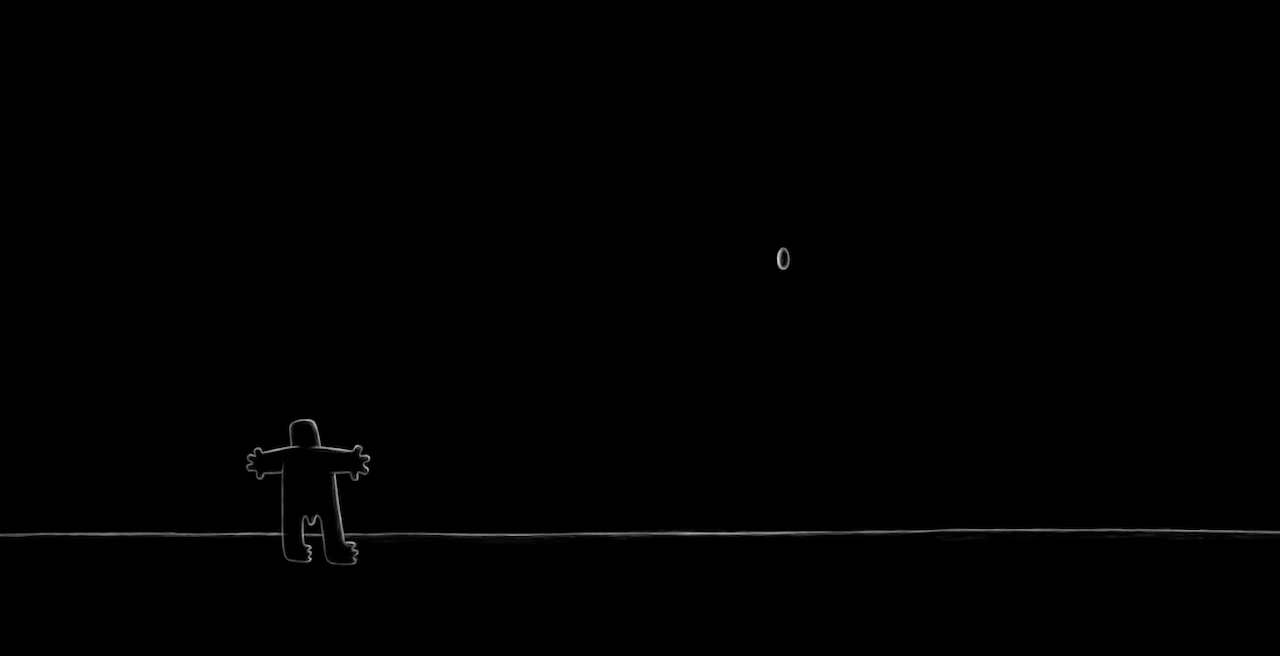

Festival programmers thought, “Put the two scratchy films together.” So I saw hers a couple of times, and I thought, “This is the Queen of Scratch. I’ll retire from the scratching business and go into simple stick-figure characters.” So I did that for 15 years. But we talked about how Altötting is almost a prequel to Ring of Fire, so I needed a scratchy element.

I didn’t know Regina too well, but I phoned her up and said, “I have this film, and I have two possibilities: either I rip you off in a very bad way or you join in.” So we came up with a deal: I’d help her out on her film [Uncle Thomas: Accounting for the Days] a little bit, and she’d transfer the Virgin Mary bits of my film into Her Holy Beautiness. She not only agreed, but got her partner Abi Feijó to come onboard. Abi became a co-producer with Ciclope Filmes and secured the finance for these magic Pessoa bits.

There are two parts to the film. One is the stick-figure stuff — I managed to do that myself, with my team of people. The other is the Virgin Mary stuff. I did the line drawings. Before we started the animation, she did a couple of key drawings based on my line designs. She transferred her own style onto it, with all the scratches … a thousand beautiful things that dance about. She was crucial to making the film work.

Something I’ve noticed in your films is the presence of the color yellow, especially in moments of epiphany, or when there’s a numinous power coming out of an object. Altötting is no exception. Have you always been aware of liking this color?

That’s a tough one. I grew up in a cellar. There was not enough space; we didn’t have enough money. I grew up for around ten years in a place with no light. So the yellow of the sun became a symbol of hope. That’s probably a sixth of the answer to your question.

You’ve been teaching animation for around 20 years. This is the first film you’ve completed since becoming director [in 2015] of the animation program at the Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg. How have teaching and directing the institute changed you as an artist?

It has not changed me as an artist, but it occupies my time a lot. It’s a clear disadvantage for the work. But every clear disadvantage has an advantage lying within. I’ll no longer do anything, as an artist, that I don’t want to do. Nobody can force me. So there’s a chance to keep the work pure, because you don’t have to fuck around with the shit.

You mean commercial work?

I wouldn’t call it commercial work, because everything has a commercial aspect. I’d call it poisoned work. One thing about the teaching: you have to reflect. What the teaching teaches you is to be able to step out of your own work. This can be of some use. My work isn’t the center of the world, although it sometimes looks like that to me.

Do you show your work to your students?

I never used to, but I’ve started to in the coronavirus crisis. I thought that I now have to make a direct connection — I can’t afford to separate my work from the teaching anymore. So I started sending the students a drawing a day, and in order to keep the distance as minimal as possible, I recommended to this new intake of students that they watch some of my films. [Video below: an installment in Hykade’s new online course.]

Altötting is premiering at Annecy’s virtual edition. How do you feel about the film debuting online?

[The festival’s artistic director] Marcel Jean is a tough son of a bitch, but I like him. I wrote to Marcel, giving him three offers to compensate for the film’s withdrawal. And he refused, in very kind words, each one of them. He forced me to eat my hat. I talked to the Canadian bunch later on. They said, “You know, Marcel Jean [who is Québécois] is ahead of us all, and you know why? He’s the only one who’s been in the army.”

So I put it in the festival. I wanted the premiere to be on the big screen, but I realized that if I withdraw it from Annecy now, I have to withdraw it from all the other festivals, and then it will be lost. The whole crisis is much bigger than a little short animated film. Everybody has to make a sacrifice.

(This interview was edited for brevity.)