‘Everything’ Creator David OReilly On The Hard Truths Of Moving Away From Animation

David OReilly’s shorts have had a lasting impact on the animation community. Please Say Something and The External World are two of his groundbreaking pieces, and the director is now equally known for the subversive ‘Alien Child’ video game sequence in the Spike Jonze film Her, and the ‘A Glitch is A Glitch’ episode of Adventure Time.

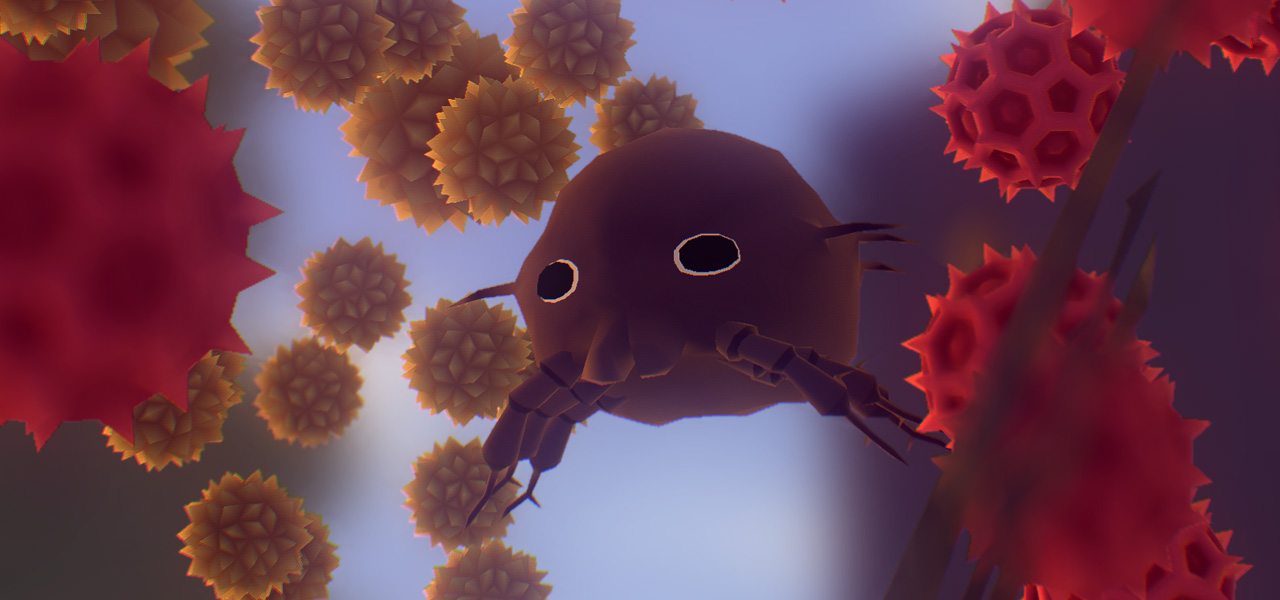

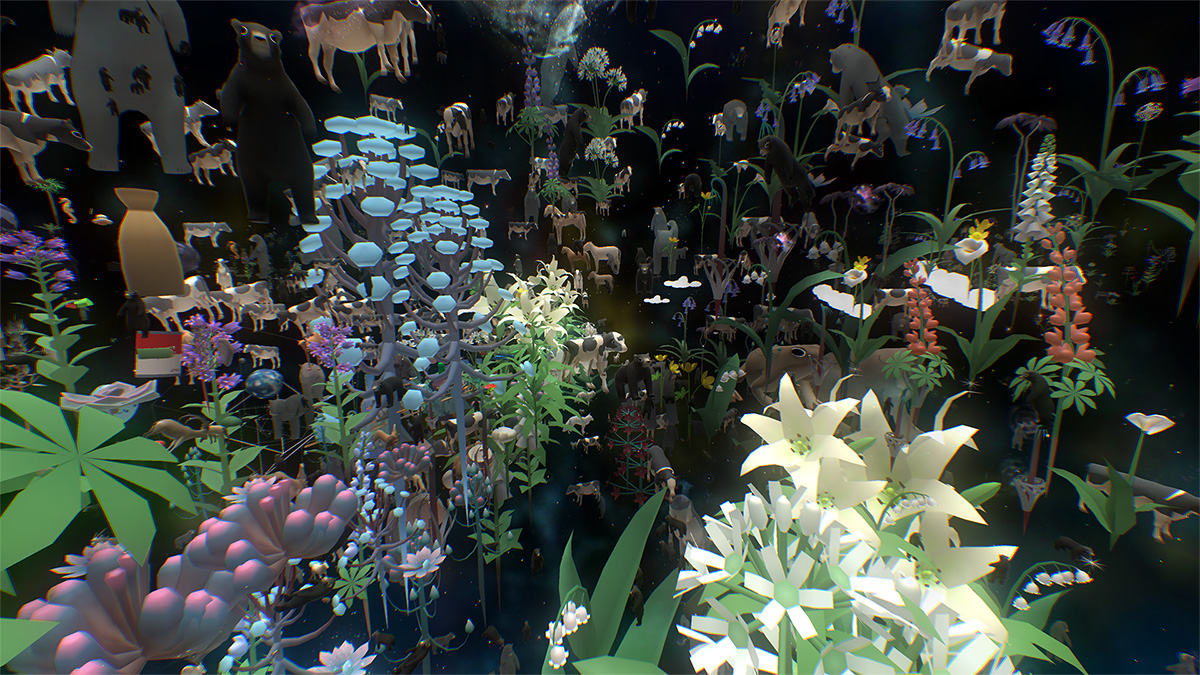

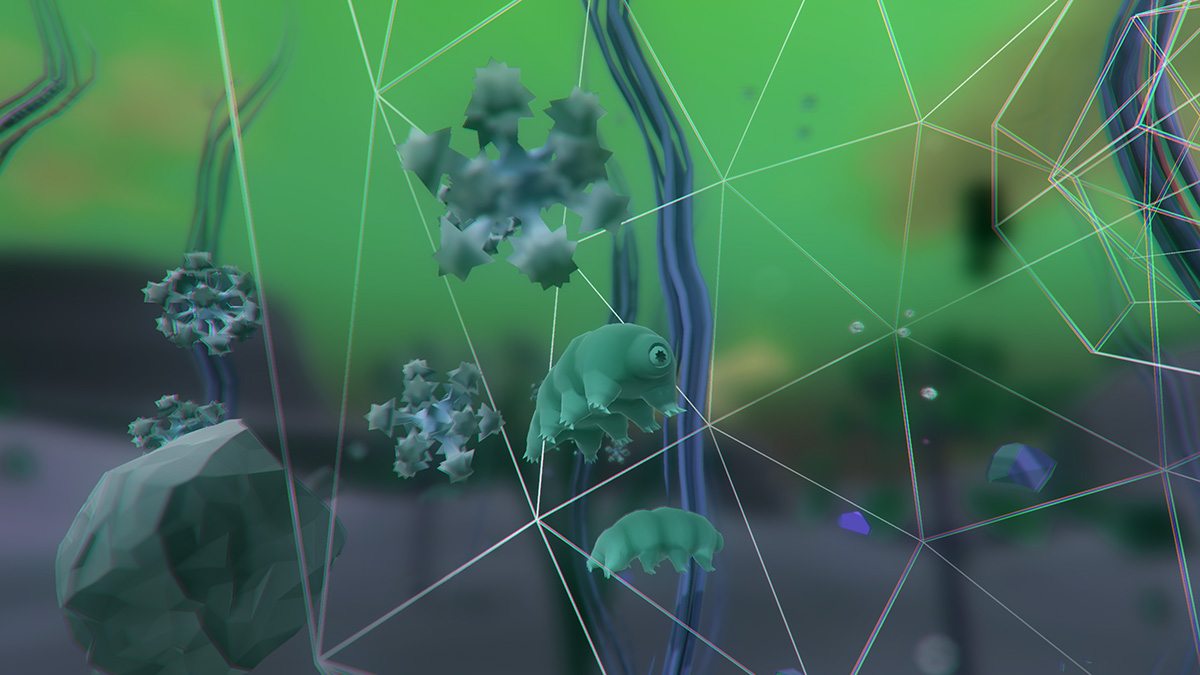

But despite the popularity of those works, OReilly says that animation has been a tough field for him to continue in. That’s why the filmmaker has moved into games, in a big way. After his breakout hit, Mountain, OReilly set to work on a new game called Everything. It’s hard to explain exactly what Everything is — OReilly describes it as “a procedural, AI-driven simulation of the systems of nature, seen from the points of view of everything in the Universe” — but it’s clear the aesthetics introduced in OReilly’s animated shorts remain present in the game.

Cartoon Brew caught up with OReilly on the eve of Everything’s release on Steam to find out more about his shift from animation to games, why he found animation so hard, and what went into making Everything the ethereal experience that it is.

Cartoon Brew: Can you talk about your move away from animation into games, including Mountain, and then into Everything? What led you down this path?

David OReilly: I became fed up with animation for several reasons. Even though my work had a big impact, I kept going broke making film after film, and even doing high profile jobs was not very sustainable for the kinds of projects I wanted to do. In animation you tend to always be getting shafted by people. People just love shafting animators all day long for some reason. And very few really appreciate what you’re doing.

I also know many people who direct animated features or have their own TV shows and they’re not exactly happy people, which is to say, most of them are miserable. So it started feeling like a dead end. At the same time I started playing with game engines and getting ideas in that direction, so I just followed that.

In terms of your short filmmaking, can you talk about some of the challenges you faced doing that kind of work, both from a technical and financial perspective? Do you see games as a viable alternative to animated short filmmaking?

David OReilly: Making shorts was always an uphill battle, but I had a lot of fun doing it. I earned and spent huge amounts of money doing jobs to make things that I released for free, and I would probably do it again if I could, but you really don’t get credit for it. You quite literally have zero credit from doing it. People assume you’re getting free money or grants, which for me was never the case.

The difficult truth is that the vast majority of interesting animation is experienced by people as random internet junk, and not this incredible artform it might be to you. So I made Mountain which was a completely different direction, and it became the first time I made any real money with my own work. And I wound up spending it all again, so clearly I haven’t learned very much.

For Everything, was there a moment when suddenly you knew what this game should be? How did it come up in your mind, and how did that change over time?

David OReilly: The initial outline for Everything is basically the same as what you see in the final game. The entire idea came very quickly one day; it’s a very simple thing but it took years to pull off – and it definitely evolved over time and took directions that could never have been predicted.

Every single aspect of the game was created from scratch so there’s hundreds of little stories of how systems were created and started affecting each other. It’s a really organic process compared to filmmaking; they are really very different processes. That’s a whole book I’ll probably never write.

It feels like you have really switched up conventional game-making. You can almost choose not to play the game and just observe. How did you balance the mix of gameplay, simulation, and storytelling?

David OReilly: I just follow my intuition on what will or will not work. It’s not too different with animation; you need to make a million decisions and know how to move on. I try to make the best thing I can possibly make, and I rely on people being open minded when they approach my work.

In every project there are certain rules I have to break in order to accomplish the bigger ideas, and this will sometimes repel people, but if you can get your brain to go along with it, you’re in for a good time. I think the whole joy of animation, or games, or any kind of art, is in getting your brain to go along with things, be they concepts or stories or even the shape of a nose or eyeball.

How easy or hard was it to translate what you knew from your other film projects to game development?

David OReilly: Every skill I ever learned in animation has carried over to games – from the technical side to how I run production. There’s certainly a lot to learn, but also a lot I was prepared for. I’ve always felt that the basic level of discipline required in animation makes a lot of other things easier.

Like, how drawing the human body makes every other kind of drawing easier. I have always found this to be the case, the level of skill required to animate a character walking across a room saying some lines is greater than 90 per cent of other creative tasks that actually exist in the world.

Everything is currently available for PS4 and Steam.