Director Chris Renaud On ‘The Secret Life of Pets’

Since launching in 2007, Chris Meledandri’s Illumination Entertainment has been one of animation’s biggest success stories, turning out one huge hit after the next, and doing so with budgets that run half the cost of the major Hollywood animation players. With The Secret Life of Pets, being released today in U.S. theaters by Universal, the studio seeks its first blockbuster that isn’t related to the Despicable Me franchise.

The studio’s fifth fully-animated feature, Secret Life of Pets also marks the fourth film that has been either directed or co-directed by Chris Renaud. Illumination’s star director didn’t begin his career with dreams of directing animation. Renaud’s art career began as a humble graphic designer in the sports entertainment industry where he created mascots for the NFL, NBA, and Foot Locker, and he later worked as a comic book artist at Marvel and DC. Later he switched to designing children’s shows like Bear in the Big Blue House and It’s a Big Big World, and eventually landed as a story artist at Blue Sky Studios, where he met Meledandri, then-president of 20th Century Fox Animation.

Renaud’s unconventional background is a nice fit for Illumination’s idiosyncratic approach to creating animated films, which often defies industry protocol. For example, as Renaud explains in the interview, Illumination didn’t use an in-house story team on Secret Life of Pets. All the story artists worked remotely, an arrangement that would be unthinkable on any other major studio film.

In spite of (or more likely, because of) these quirks, Secret Life of Pets feels like a breath of fresh air in the contemporary big-studio landscape. The film, filled with an endearing and appealing cast of characters, never loses sight of its mission to entertain audiences, which it does expertly from beginning to end, while avoiding the emotional manipulation and social messaging that weighs down so many other animated features.

I spoke with Renaud recently to learn more about his comic influences for The Secret Life of Pets, Illumination’s unconventional workflow, and the studio’s fluid production process that allows humor to be added in during every stage of production.

Cartoon Brew: Secret Life of Pets is the fourth feature you’ve directed. Many animation directors don’t even reach a fourth film because of the time-consuming nature of the medium, yet you’ve done it in under 10 years. How do you view your own body of work? Do you feel like you’ve developed a creative voice over the course course of these four films?

Chris Renaud: Yeah, I’d like to think so. Obviously the scale of one of these movies, you’re working with a large team; you’ve got studios and producers. But I do think that I’ve been fortunate with Illumination, and before that, with the short I did for Blue Sky, to develop somewhat of my own voice. I think at the end of the day, for any artist or filmmaker, that’s really all you have to offer. And the things that I do tend to reflect my influences, which are more cartoons, like the Warner Bros. cartoons especially. So I always had a great time working with the Scrat character in the Ice Age films, and the short I was able to write and co-direct [the Oscar-nominated No Time for Nuts co-directed with Mike Thurmeier]. And carry that through to Despicable Me. Silly things like Gru, when he’s trying to break into Vector’s hideout, suddenly there’s a shark in the sewer, that kind of nonsensical storytelling is certainly something that I love and try to put in the things that I direct. I was fortunate with the Despicable Me films that Pierre [Coffin, the co-director] also shared that voice, and the love of these cartoons.

One of the things that stands out in Secret Life of Pets is how sharp the comic rhythms are in the film. I don’t think you can reach that level if you’re directing one film every five years like at a lot of these other studios. Like those classic Warner Bros. cartoons you cited, those guys were just constantly putting out films one after the other, and learning their craft through repetition. I wonder if this fantastic sense of comic timing you’ve developed can be attributed simply to the sheer amount of animation that you’ve been making?

Chris Renaud: I think there’s some truth to that. In some ways the word “cartoon” has become, certainly maybe in the feature film world, sort of a bad word, but I don’t really see it that way. There’s some fun to be had by mining and developing that kind of comedic sensibility that’s a little faster paced, a little bit more physical comedy. And those are the things that I really enjoy doing and trying to implement. Like anybody who makes film, they’re just the things that make me laugh, and we’ve been fortunate so far, that the audience is laughing along with you.

It’s funny you mention the word “cartoon” is kind of a dirty word. I was reading a review of the film in a major publication and they described the characters as “downright ugly,” and I was shocked because they’re incredibly visually appealing, yet they’re also cartoony and caricatured in a way that you don’t really see in a Pixar or Dreamworks film. I feel a lot of people nowadays mistake something that looks funny for being ugly, simply because people don’t know what cartoons are supposed to look like anymore.

Chris Renaud: I know the review that you’re referring to, and I actually think that was meant as—I don’t know if I’d call it compliment, but…I’d call it a left-handed compliment. [laughter] You know a lot of that too I would attribute to Eric Guillon who has been the character designer and production designer for every film that I’ve been on. He was introduced to me by Pierre [Coffin], and Eric is truly a cartoonist and a gifted one.

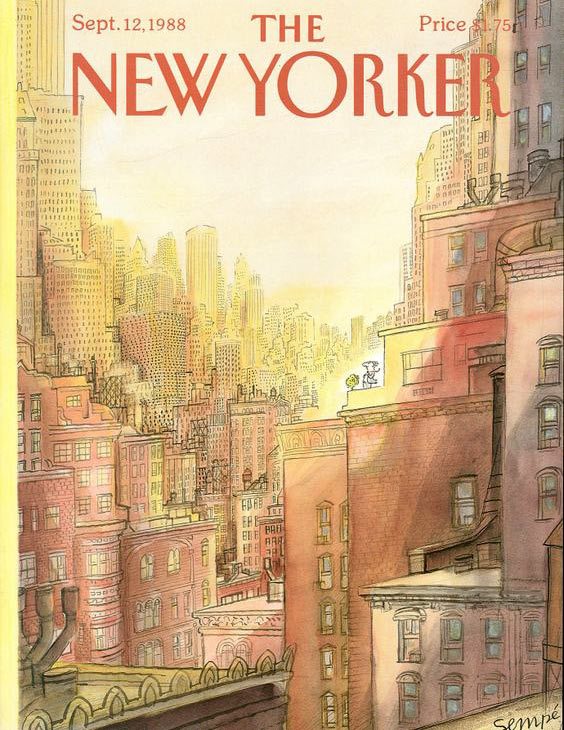

Some of the influences that we talked about very early on were The New Yorker cartoons, and also The Far Side by Gary Larson. Eric and I would talk about both of these things. And The New Yorker has actually compiled books of dog and cat cartoons. They have that very famous one of two dogs on a computer and one dog says to the other: “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” [laughs] That sort of encapsulated—for me anyway—very early the tone of this movie. And from there, we talked about the artist Sempé, the French illustrator, and his New Yorker covers, which were a big inspiration for Eric and for the look of New York City in this movie. And if you think about what Gary Larson did in the Far Side cartoons, one of my favorites that Eric and I would both talk about was where it says, “How nervous little dogs prepare for their day” and there’s a dog and an espresso machine. We even have a little homage to that in one of the scenes in the movie where there’s a chihuahua drinking from an espresso machine in the party sequence. Truly you can’t get more cartoony than the single panel cartoons of The Far Side and New Yorker.

It’s funny that you looked at Sempé because the film does feel like a French person’s romanticized view of New York City in the sense that the city is pristine and almost magical. French people love New York City, but I think they have a very different take on it than the American view of the city, which is more raw and gritty.

Chris Renaud: You know, I lived in New York about 14 years, and in a weird way, I have an idealized view of it myself, too. I live in France now, and when I think of the United States and I think of home, quote-unquote, I do think of New York. It was a great thrill for me and my family, when we did the premiere [of Secret Life of Pets] in New York. And I think you’re right. I always make the joke that people in New York have photographs of Paris in their apartment, and people in Paris have photographs New York so it’s kind of like that. [laughter] We also used Sempé as an influence to heighten the scale. Sempé’s work [will have] like a wall of windows, and then there’d be two little characters in the corner. I felt that pushing the vertical nature of the city, almost treating it like a curtain in some ways, would reinforce the perspective of these little animals lost in this giant metropolis.

Was New York part of the concept from the beginning, or did the location develop over time?

Chris Renaud: It’s funny…I was trying to remember if we ever had another location. I feel like we did but I don’t remember, and I guess that’s an indication of how quickly it went in and out of our minds, because when we were developing this, we were all over the place with what story to tell. And one thing that we settled on very quickly was using New York, because it just felt like it could lend itself to this idea of pets moving through the environment sight unseen by human eyes. Otherwise, if you think of L.A. or if you think of even Paris, it would be hard to believe that. But certain things, like a window washer platform or a construction chute or fire escapes, and the vertical nature of [the city]—these felt like ways that the animals could be moving from place to place without us humans ever knowing about it.

According to the press materials, the film is based on Illumination head Chris Meladandri’s concept, and then Cinco Paul, Ken Daurio, and Brian Lynch wrote the film. At what stage did you come onboard the project? Were you there developing it in the beginning, or did you come on board after there was a script?

Chris Renaud: I was on it from the very beginning. The concept started with Chris Meladandri basically saying, ‘What about you doing a movie about what your pets do when you’re not home?’ But from there, we had to develop our characters, our story; we built from there. One of the fun things about it—and one of the big challenges—was figuring out what story to tell. A lot of the moments and some of the storylines are derived from not just mine, but Chris’s and the writers’ and the animators’ own memories and experiences of pets in our lives. It was truly like building a house brick by brick as we figured out the story and then what characters we wanted to incorporate. And it’s one of the reasons there’s such a large cast because we wanted to feature not just dogs or cats, but every kind of pet. We probably don’t have everyone, but we’ve got a lot, so it was an opportunity to incorporate a storyline with a guinea pig, with a bird, all kinds of different animals.

With the Flushed Pets, you see a lot of unconventional animals, and I thought the film suggested a type of pet hierarchy where dogs are the pets that people keep, and the more unconventional ones sometimes get tossed.

Chris Renaud: That’s totally true and that’s kind of the way that idea evolved. The writers were working with that, and I remember telling a story when I was in college, I would go to this kind of odd pet store and this guy had a monitor lizard, which is basically like a komodo dragon in an aquarium, and it was huge. It was probably a yard long at least, and I remember asking him why this thing was there? He said, ‘Oh yeah, somebody bought it when it was six inches long.’ We would talk about things like that as we developed the Flushed Pets. That’s just my example, but everybody had these thoughts, and again brought personal experience and memories to making the film.

To talk a little more about developing the story, how did you interact with the story artists on Secret Life of Pets because you’re in France, but I know some of the story artists were based in the U.S. Did you have an in-house crew of story artists, or was it all long distance?

Chris Renaud: We actually do have a crew of story artists here in France, but on Secret Life of Pets, everyone I worked with was in the United States. The only two storyboard artists that were here in France were myself and [co-director] Yarrow Cheney. I would work remotely with the storyboard artists—call them on the phone, or very often what I’d do is highlight a panel in the delivered PDF of panels and say can you add this or there’s some [dialogue] changes and that kind of thing. So it’s a very remote process because the team that I use is based in the United States.

That’s amazing…

Chris Renaud: The other directors here—Kyle Balda, Pierre Coffin, Garth Jennings—they’re using our story team here in France. When I first came over for Despicable Me, all my story guys were in the U.S. besides myself; I did a lot of the storyboarding on that film. So I’ve been comfortable with that system. And then by the end of Despicable Me, we did actually have one other storyboard artist here in France, and then the in-house team slowly built from there.

So how do your story artists pitch a board to you?

Chris Renaud: They don’t. [laughter] They come up with the idea, and then I take a look at it. Sometimes if it’s a very complex scene, we’ll do a rough pass first, so I can have a conversation, but it varies. Sometimes it’s a conversation that evolves based on roughs, or I’ll say, ‘The script says this, but let’s try this.’ And then once I see what they’ve done, then I’ll come back and say, ‘Let’s try this, let’s try this.’ There can be great value in, particularly depending on the storyboard artist, getting somebody’s take on it. What I always hope for is something better than what I’ve asked for. And man, some of the surprises and the great work that has been done by some of our storyboard artists really helps make the movies what they are. That’s my favorite part of the process, the storyboarding, because if the movie’s working as an assembly of rough drawings with bad scratch voices and temp music, or even just limping along somewhat successfully in that form, that’s when you know you’re on the right path.

The most successful animated film this year so far is Disney’s Zootopia and they didn’t have their story figured out when they start animating. My sense is those kind of wholesale story changes don’t happen as dramatically at Illumination, but I’m curious on Pets, how firm was the story when you started animating the film?

Chris Renaud: I know the story I think you’re talking about with Zootopia where the animals had collars. For us, much like I would say at Blue Sky, Disney, Pixar, there are similarities in that it’s a very iterative process. In the sense that as we’re making it, and if something’s not working, or working as well as we’d hoped, we’d certainly allow ourselves the freedom to make changes. That’s sort of the beauty and the curse of animation: the malleability allows you to constantly improve and constantly work on it. By the same token it almost feels like it’s never done. You keep tweaking and tweaking. But I don’t think once we were into animation, we had a major [change]. In fact a lot of the beginning of the film which I think is something audiences really respond to, came out of our animation testing.

Really?

Chris Renaud: You know, the dachshund with the the mixer, Chloe with the food in the refrigerator. What happened was we were trying to figure out the beginning of the movie, both storyboard artists and the animation team. I talked to them about what are some ideas for what your pets do when you’re not home. We just started brainstorming, and some of the animation tests that came out of that are at the beginning of the film, including Leonard the hard rock System of a Down poodle.

We sort of shaped that scene around these great ideas that came from the animators. Some of them came from the writers too, and some of them came out of storyboarding. We knew what we wanted to do rhythmically, like doors shut and then boom, magical things happen, so we were working around that idea. But it was very organic in how it came to be. We allowed ourselves room for discovery in animation so that we could incorporate that into the film. And from a very early date, we all felt that animation was really a key to the success of this movie because we were trying very hard to animate animals as they are, not an anthropomorphized version of them—to capture dogs and cats from anatomical accuracies to gross behavior, all that stuff that if you have a pet is part of life.

That opening, which was used in the teaser, sold the film for a lot of people, I think. It’s funny that those shots were some of the first things you actually animated.

Chris Renaud: I think that this movie is unusual in that the animated performance is such a huge [part]. Don’t get me wrong, of course it’s a part of every movie, but [here we were] capturing the little behaviors so that when people watch, [they say], ‘Oh yeah, my dog does that.’ I have to give a lot of credit to the animation team, led by our animation directors Julien Soret and Jonathan del Val. They really pushed towards, like, ‘Okay, how would a dog do that?’ A good example is that shot of Max climbing the fire escape. I think if you had animated that out of your head or out of memory, you would probably just have him walk up the stairs, but we did some research, and when dogs climb a ladder, they’re very ungainly and awkward at it. They sort of hop. And it was that kind of stuff that we’d always try to push ourselves to find the solution that felt more true, or more based in how a dog or a cat or a bird would actually complete that certain action.

How do you work with the animation directors and the animation team?

Chris Renaud: The animation directors work with the team obviously throughout the day, and then I have rounds essentially twice a day, which could be anywhere from an hour to close to two per round at the peak of production. At the beginning, when I kicked off the animators, I had a bunch of silly Youtube clips—there was one compilation I had called “Animals Can Be Jerks” [laughter[ and it was all crazy stuff of animals just being animals, but in funny ways.

[This was] to launch them on the idea that we want these animals, even though they’re stylized, to feel like real animals. That was kind of the big idea in my head from an animation point of view, and the animation directors embraced that. Of course, when we needed an anthropomorphic behavior, we would do it, but we tried to push ourselves to find a solution that felt true to an animal. Dogs, which are the easiest to cite I suppose, they have things available to them to express emotion that we don’t, like ears dropping or the tail drooping, so we tried to find those things that create some distinction. What’s been fun about the movie is that when people watch it, they see their pet in it. I think that’s a real tribute to the animation team and how well they captured what animals are like.