Delivering Quality On A Tight Schedule: Speaking With ‘Ping Pong’ Art Director Aymeric Kevin

Background art, as the name implies, tends not to be the focus of attention in discussion about animation, but often features fantastic work by talented artists. Labyrinth Labyrinthos (1987, dir. Rintaro) wouldn’t be the same without Yamako Ishikawa’s art. Shichiro Kobayashi’s expressive art helped define the shows he worked on in the 1970s, like Aim for the Ace! and Gamba’s Adventure.

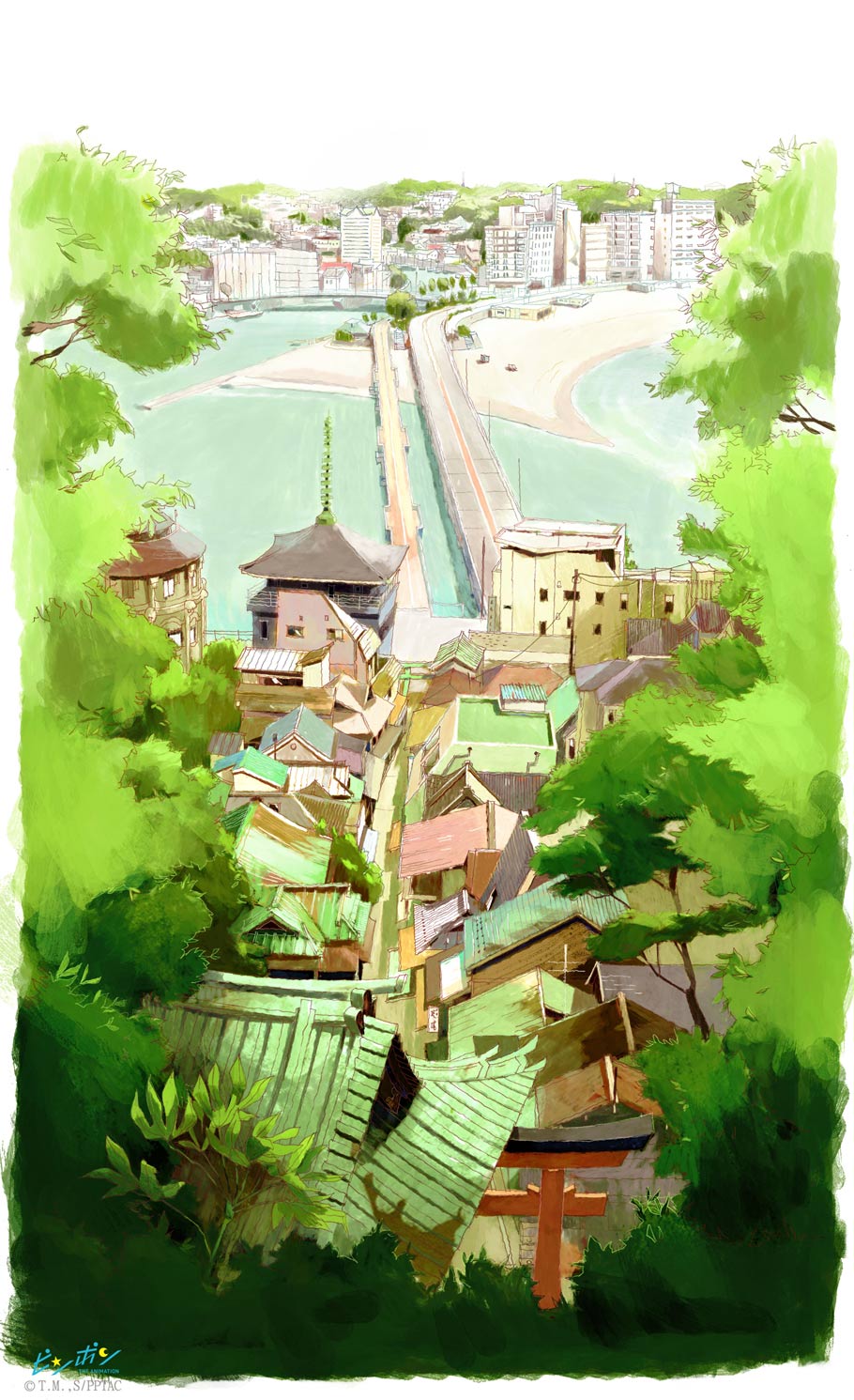

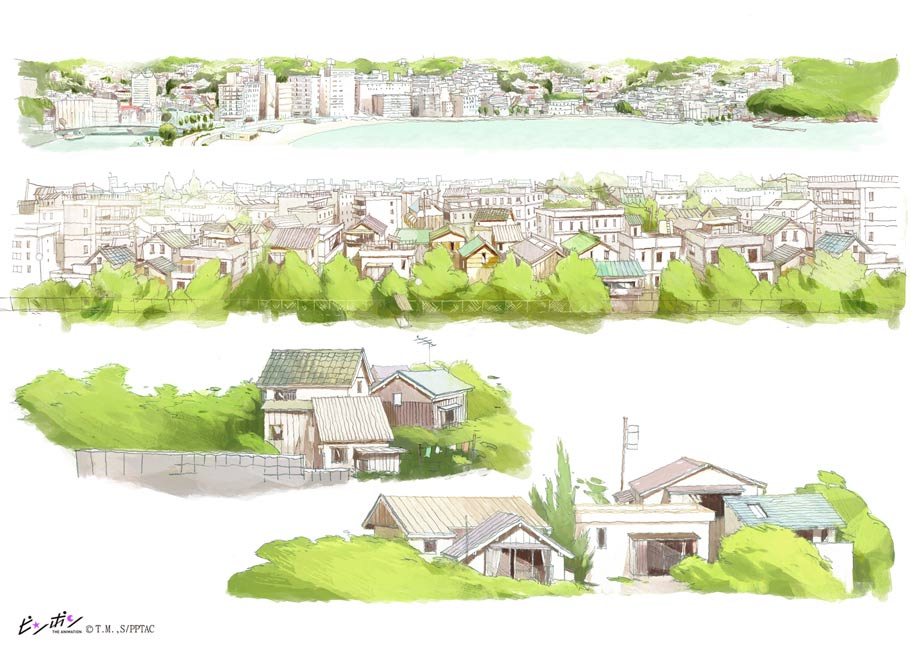

The same can be said for Ping Pong’s background art, directed by Tokyo-based Frenchman Aymeric Kevin, whose work has been featured in the past on Cartoon Brew.

For Masaaki Yuasa’s latest show, Aymeric worked at a grueling pace, nevertheless producing many beautiful images that helped define the show, even while working on a style quite different from what he was used to. How did Aymeric and his team manage to produce so many quality backgrounds on such a short schedule? Aymeric was kind enough to answer a few of my questions by email to shed light on the background art of Ping Pong.

Cartoon Brew: What got you interested in animation?

Aymeric Kevin: Japanese anime. Like it was the case for many, it started as a hypnotic fixation with the shonen genre. Anime had a large presence in France in the 1990s—shows like Dragon Ball, Saint Seiya, City Hunter, even Fist of the North Star—there were many shows being aired on TV at the time. Later on, Masaaki Yuasa’s Mind Game and Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke swept me away and to this day remain my favorite films. It was during high school when I become really fascinated in the animation process through the making of videos, peeking into the world of the many devoted people working together, sweating over the desks, crunched over focused on a singular mission. This made me want to be in this industry. I still spend hours re-watching the documentary, How Mononoke Hime was Born (Mononoke Hime wa koushite umareta). For those who have not seen it yet, I highly recommend it.

Cartoon Brew: Gobelins has a good track record of producing remarkable student films. What makes Gobelins different and what did you learn there?

Aymeric Kevin: The rhythm here is quick; the moment you are accepted into the school the pace of progression within their walls accelerate. The fact is, they usually choose people with solid drawing skills to begin with, and that is probably why the fast pace is sustainable. Gobelins likes to remind people they are not going to teach anyone how to draw; they teach how to animate. Yet they offer a very comprehensive course where students are taken through every stage of the animation production. Knowing all of the stages and processes helps you make better decisions whatever you end up doing in animation.

What I have mainly learned though started as a realization during the first entrance exam. I was in a large room with rows of tables, but more importantly, rows filled with hundreds of applicants. It was clear: there are a lot of drawers out there. This emulation, this reality of competition, remains strong and vigilant throughout the years at Gobelins. Whether it is good or bad, it undeniably pushes one to do their best at all times.

Cartoon Brew: How did you come to work in the Japanese animation industry?

Aymeric Kevin: Near the end of working two and a half years in France, I had the opportunity to collaborate on a French/Japanese production where I met Eunyoung Choi, an incredible episode director/animator for shows like Kemonozume, Kaiba, Tatami Galaxy, etc. Since working together from the first gig, she has been my guardian angel in this industry. She proposed to me to make the backgrounds of Masaaki Yuasa’s short animation, Kick Heart, at Production I.G. It was a dream come true. I left everything behind, shut down my life in France and flew to Japan. But none of this would have happened without my wife Yoko; she supported me so much to make this possible as moving to Japan isn’t an easy process.

Cartoon Brew: You recently pulled off the impressive feat of drawing all of the background art in episode nine of Space Dandy. How many paintings was this and how long did it take? And what compelled you to do it?

Aymeric Kevin: Eunyoung Choi’s episode has 340 cuts, which is a little more than usual, as the average for a Japanese TV show is 250 cuts. While at Gobelins, I heard about Michio Mihara directing and animating a complete Kaiba episode single-handedly. I thought that handling a complete production stage alone was pretty cool, and it made me want to do the same someday. I thought it must feel like a baseball homerun; I sensed the satisfaction would be quite strong with such an accomplishment. My first opportunity to do something like this was on the short Kick-Heart, so then the idea came naturally for Space Dandy #9.

Eunyoung Choi and Shinichiro Watanabe immediately accepted as we had some time ahead of us and Japanese studios are currently struggling to find background staff. It took four-and-a-half months to complete, with some time spent in parallel working on Masaaki Yuasa’s Adventure Time episode. This method helped to keep the art direction on a homogeneous level, which is sometimes a real challenge when managing a bigger team. But the “home-run” chance doesn’t come often as animation deadlines are tight, especially in Japan. For example on Ping Pong, we only have one week to make a full episode.

Cartoon Brew: One week? Is that true for the animation as well or just for the backgrounds?

Aymeric Kevin: Just for the backgrounds. For the whole animation process, an episode schedule could vary between two to three weeks. But that includes Genzu (Layout), Genga (Key Animation), Nigen (Second Key Animation), Sakkan (Model/Animation Correction), and Douga (In-Between), which means the pace is incredibly fast.

Cartoon Brew: Was Yuasa storyboarding an episode per week?

Aymeric Kevin: Yes.

Cartoon Brew: So what would a more typical schedule be for a show like Space Dandy?

Aymeric Kevin: For Space Dandy, the episodes are made way ahead. On the few episodes I worked on, the schedule would vary between three to four months. While it is more comfortable, the animation teams are generally smaller, at least until the deadlines get too dangerous. But that isn’t typical either. Japanese anime episodes are finished close before airing on TV, and from what I have seen, the time frames vary from one to three months.

Cartoon Brew: Before Ping Pong, you were the background artists for Masaaki Yuasa’s Kick-Heart. What is it like working with Masaaki Yuasa?

Aymeric Kevin: Witnessing him working on a daily basis is an incredible experience and everyday I feel truly lucky. As a fan, it is a magical feeling! He doesn’t know but I feel like I am his secret apprentice. I look and try to study everything he makes. He is a role model for me. At one point he was directing on Adventure Time, Space Dandy and Ping Pong simultaneously. A normal person would have melted under the pressure and fatigue but he seemed so calm, even though he told me that he was sleeping thirty minutes per night during that period.

Cartoon Brew: What are your thoughts about Taiyo Matsumoto’s unique art style, and what is your approach to the art of Ping Pong?

Aymeric Kevin: I don’t know why, but it is hard for me to compose specific thoughts about Taiyo Matsumoto’s art style. His essence is beyond anything conceptually conceivable, so I can only think of one word: freedom. Each of his frames looks so unique. For a lot of artists, it may be the ultimate goal to achieve, I suppose. To be able to make, create, as instinctively like breathing air. I’m sure it must not be that easy for him. but it is what it feels like when enjoying his work. With the Ping Pong backgrounds, I am determined to not disrespect his and Yuasa san’s work and vision.

Cartoon Brew: Could you walk us through the production process for one background image in Ping Pong?

Aymeric Kevin: For Ping Pong backgrounds, we use pencil line and digital coloring. Nowadays it is more common to see fully executed Photoshop backgrounds as it is much faster, but in our case, it is very hard on a pen tablet to get Matsumoto’s dynamic hybrid of trembling yet controlled lines.

So from the animator’s layout, I would have to draw the line on paper and with the precise line style. It took me months to get a line good enough as it wasn’t my specialty and I am very thankful to Yuasa san and Eunyoung Choi for sharing their tips.

For the coloring, I made a color script for each episode, so I would refer to them and paint the background in Photoshop. We use a special brush set, specifically made from real scanned brush strokes. This is why it can sometimes look like traditional paintings; it was important to stay true to the organic touch that we sense in Matsumoto’s manga.

My role is to make the 25-30 key backgrounds for each episode so I try to not to take more than 3 hours per background, so I can at least make five per day. The rest of the time is spent on working with the background team and giving retakes.

Follow Aymeric Kevin’s work on his blog, Tumblr, and Twitter.