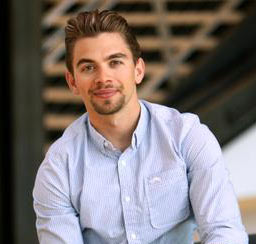

Oculus TD Max Planck: “We Want to Inspire the Virtual Reality ‘Citizen Kane'”

Distantly descended from the Nobel-winning scientist of the same name, Maxwell Planck has instead channeled his scientific and creative smarts into shaping the future of animation and VFX.

Arriving at Pixar in 2004, Planck worked in various technical and engineering capacities on Wall-E, Brave, Up, and more, before leaving in 2014 to become the technical director of Oculus Story Studio (Oculus is owned by Facebook). A lifelong gamer as familiar with shooters like Doom as he is with more immersive, thought-provoking titles like Final Fantasy VII and Stanley Parable, Planck is fusing his experience with animated film and interactive gaming to help create the foundation for the future’s VR cinema.

It is a future we can see coming in Oculus’ new short film Henry, unveiled yesterday at a media-only screening in Beverly Hills, California. In fact, the short was made using the game production software Unreal Engine 4. It’s a promising experiment that Planck nevertheless sees as only hinting at the storytelling possibilities of the platform, which should more properly explode as hardware, software, and even artificial intelligence barriers are progressively broken down and surpassed.

Cartoon Brew caught up with Planck yesterday to talk about Oculus, Pixar, Henry, The Iron Giant, and the Citizen Kane of VR cinema, which hasn’t been made yet but will certainly be influenced by Oculus’ formative explorations.

Cartoon Brew: You showed clips from Georges Méliès and Buster Keaton to indicate that this is the frontier of cinematic experience. How do you see it unfolding?

Max Planck: When people first get into the Rift, they’re intimidated and overwhelmed. We found that when we made the stories of Lost and Henry too complicated, people didn’t follow them, so we actually slowed them down a lot. But speaking personally, I’ve been in VR for a year now and I’m ready to speed things up. We’re still in novelty phase and I think we’ll be there for awhile, as VR spreads out into the world. But I look toward Pixar, which had to invent technology to make their films.

Cartoon Brew: Take a bow, my friend.

Max Planck: [Laughs] Well, I got there in 2004 and was there until 2014, so the machine was already running, into a Golden Age. But it wasn’t like pre-Toy Story days, where everyone was telling them, “There’s no way you’re going to make a film with just computers and have people pay you for it.” That seemed an impossibility, so Pixar had to assemble a huge team to build their animation and lighting tools, and to train computer scientists how to light and animate. There was no talent pool out there.

The cool thing about VR is you can use Maya, Unreal Engine, and Photoshop. You can pull from the gaming and animation industries. There is a talent pool out there that already knows how to do this stuff. The hard part is being a creative director, or a director. How do you take these techniques and actually turn them into something appealing and intuitive?

And that’s where we’re at right now: We get into the experience, but we’re still disappointed. We’re at a two or a three and we’re trying to get to a 10. But we do think, and we are very proud, that Henry is an improvement, especially in scope. Lost was very cool, but it was a two-sentence story; Henry is much more complex.

Cartoon Brew: I’ve talked to a couple of Oculus people today who told me that Lost was an homage to The Iron Giant.

Max Planck: Definitely. We were very much inspired by The Iron Giant.

Cartoon Brew: Has Brad Bird seen it?

Max Planck: He has not, although Mark Andrews [storyboard artist on Iron Giant] has, and John Walker, my producer on The Good Dinosaur [and associate producer on Iron Giant, knows about it. We would love for Brad to come and see it; we’re very open about how much The Iron Giant inspired us. Actually, the reason we made Lost is that, once upon a time, Saschka [Unseld, creative director of Oculus Story Studios], Edward [Saatchi, producer of Story Studio], and I were sitting around talking about wanting to have that child-like experience again, and since The Iron Giant is one of our favorite films, we all agreed that we wanted to be in a scene from it!

Cartoon Brew: How is Henry different than Lost?

Max Planck: We showed Henry to a lot of people, and they thought it was cute and adorable, kid-friendly and family-oriented, which is what we wanted. We wanted it to be approachable, so people would trust us with their VR. It’s in a comfortable, cartoony, well-lit space which isn’t in danger of going dark. We wanted something you could show to anyone when the consumer version of Oculus came out. I mean, that’s what a Pixar film is. You know anyone can go see it.

Cartoon Brew: Since you’re admittedly still at the frontier, there is a sense that everything you do now is still an experiment. When I was watching Henry, I also wasn’t watching it, because I was exploring the environment. Do you have feel that VR film will have to be interactive, in order to focus the audience on the narrative?

Max Planck: Yeah. When we started making VR movies, we were nervous because the reason film works is that the director perfectly frames the moment. The director wants you to see this, now, for this many seconds — and now we’re giving that up. Saschka calls it “The Letting Go,” because it’s OK that people are looking around. It is their choice.

But we have found that if you put an interesting story in front of viewers, they will follow it. One reason why Lost and Henry take so much time for the story to begin is that we want to get the looking around out of the viewer’s system. One of the mistakes we made with Henry is that it is very much a left-to-right experience mostly happens in front of you. There are a few moments where it happens above you, but it is still something that you could frame. It still feels like a filmic experience. There was a scene where we had Henry run around you, but some people were like, “I’m losing him!”

So we’re still in a novelty phase, somewhat stuck with the trappings of film, but I do think we’ll get to the point that the viewer can absorb the space and become part of the story. The story will eventually evolve around the viewer. There are some pretty cool artificial intelligence problems involved with that. How do you bring in the viewer’s creativity? Maybe the story and its pacing doesn’t evolve until the viewer, and perhaps even his or her biometric readings, become involved. If you’re the type of person who looks around a lot, maybe the experience can be sped up, or maybe it can be slowed if you’re the type who looks around slowly.

It’s hard, because the reason we currently love film is that we can identify with the director’s taste and vision. That’s what you’re buying into.

Cartoon Brew: So VR film becomes an issue of active not passive reception, where viewers are also creating the experience, which opens up many possibilities but also creates many problems.

Max Planck: I’ve been a gamer all of my life, as well as a fan of pure animation. I’ve evolved beyond Quake, Doom, and Halo, although I still do play them a bit. But the games I play more are The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, The Stanley Parable, Gone Home, and other games which aim for emotional impact. I grew up with a controller in my hand, but there are many out there who have no experience with one. But with VR, everyone knows how to look around and use their hands.

Cartoon Brew: Henry seems eager to create a bond, and I think kids will pick up on that, but also love exploring his world. And they are, in turn, the frontier of reception for VR film. They will grow up with the technology, and come to shape it.

Max Planck: And they will surpass us. Today’s filmmakers are amazing because they grew up watching Spielberg and other directors, so tomorrow’s VR filmmakers are just going to destroy us. They will have known this experience since childhood, and dreamt of ways to change it.

And that’s what we want to do, and become a part of. We want to be the Georges Méliès of VR, who sets the stage for another filmmaker to come along and create Citizen Kane, so to speak. We might not make the VR Citizen Kane ourselves, but we want to inspire it.