Inside The Artist’s Studio: Sophie Koko Gate

Even on a clammy May morning, Deptford Market hums with the happy energy of people in an acquisitive mood. Shoppers drift between stalls laden with objects that look like they’ve been ransacked from local attics. There are loose dolls’ heads, mysterious coins, folders bursting with the typed transcripts of Sunday morning sermons.

“It’s important to keep surrounding yourself with interesting things,” Sophie Koko Gate says, as she buys a book whose back cover displays a close-up photo of a man’s feet. “You never know what will stay with you.”

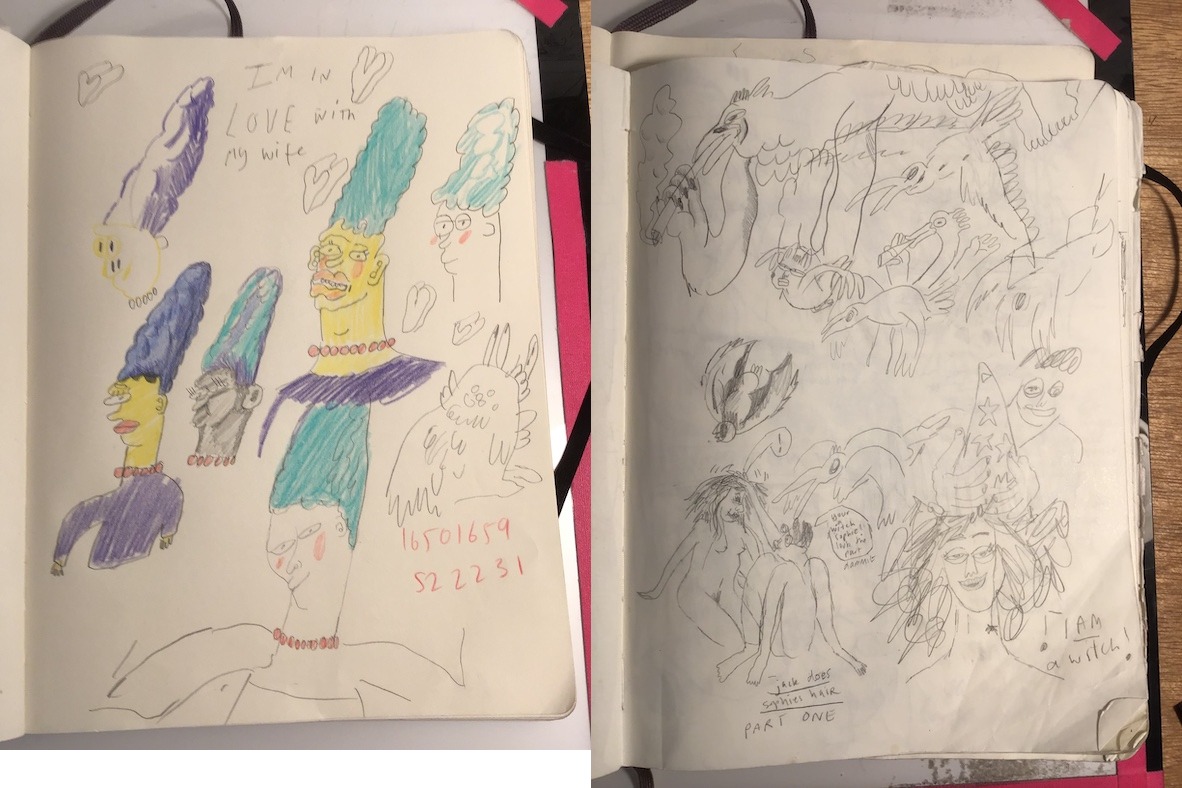

Gate’s animated shorts give some insight into what stays with her. Her surreal meditations on sex and romance are populated with flamboyantly ugly humanoids whose physical quirks are magnified to grotesque proportions. Tiny organic matter — flies, krill, the floaters you get in your eyes — clings to them, for no reason other than that Gate wants it that way.

The films are driven as much by explorations of how bodies can move and interact as by any notional storylines. Science, whether factual or fictional, provides a through line: a character in Half Wet obsesses over his body’s water content, while another in Slug Life cross-breeds humans with gastropods (U.K. readers can view the film here). Gate’s unique visual world has made waves in the animation world, earning her prizes and prestigious commissions aplenty.

Deptford, in southeast London, contains a thriving artistic community centered on the renowned Goldsmiths university. Its market is held three days a week, and Gate, who lives in the area, comes every time. She asks me to meet her there, as it is one of her main sources of inspiration. She likes to sketch the bric-a-brac she picks up and mine its second-hand books for ideas.

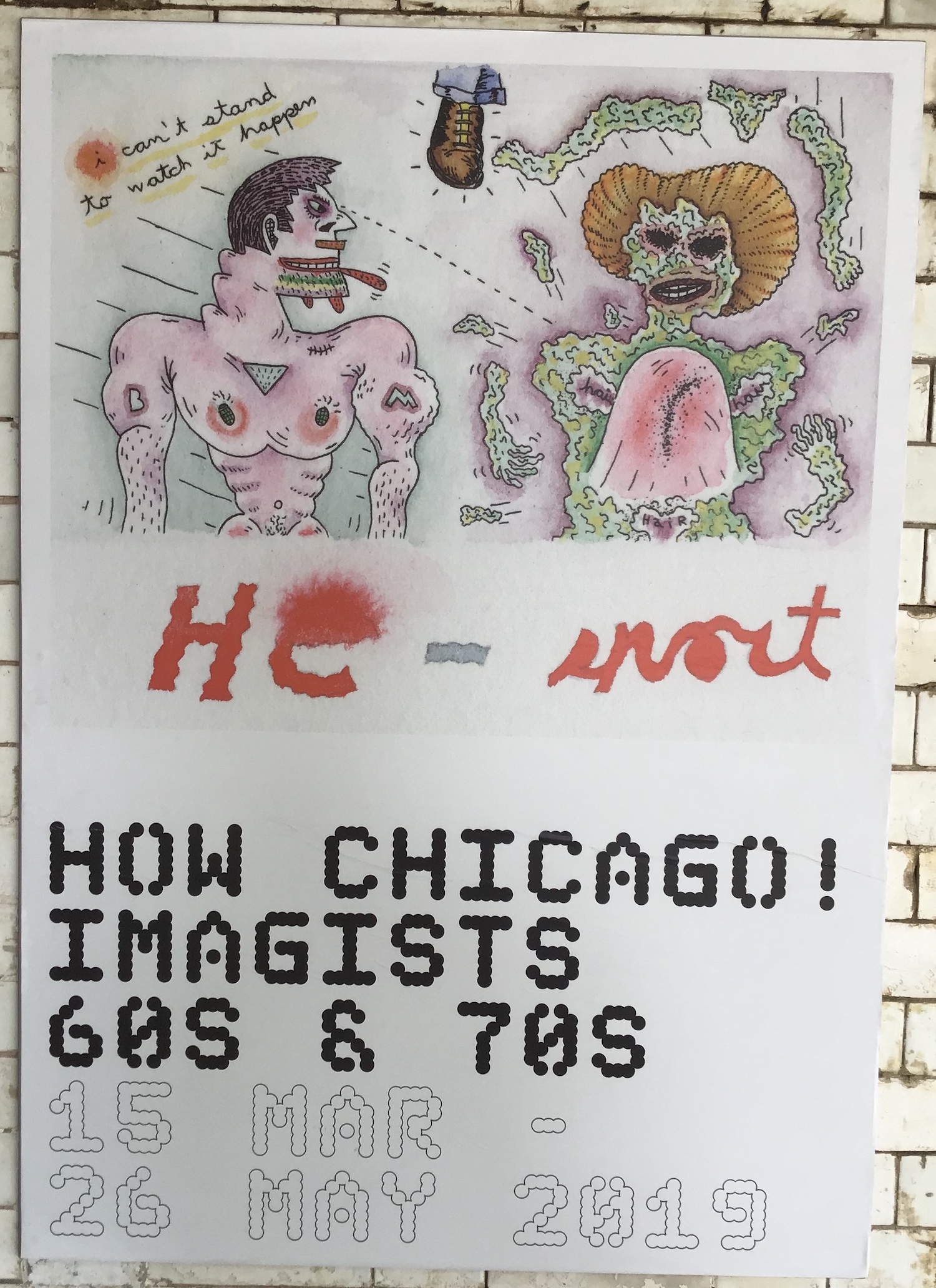

From there, it’s a 15-minute train journey to her studio in the eastern district of Shoreditch. On the way, we swing by Goldsmiths to see an exhibition of the Chicago Imagists; Gate is dismayed to find it closed. She discovered the group while on a trip to Chicago last year and was blown away. “Their work, especially Jim Nutt’s, looked like better versions of drawings I was trying to do at the time,” she explains. “Since then I have been inspired by their line work — controlled but completely mad, like surreal wobbly versions of Robert Crumb. I also like the fact that they exhibited together and helped each other out.”

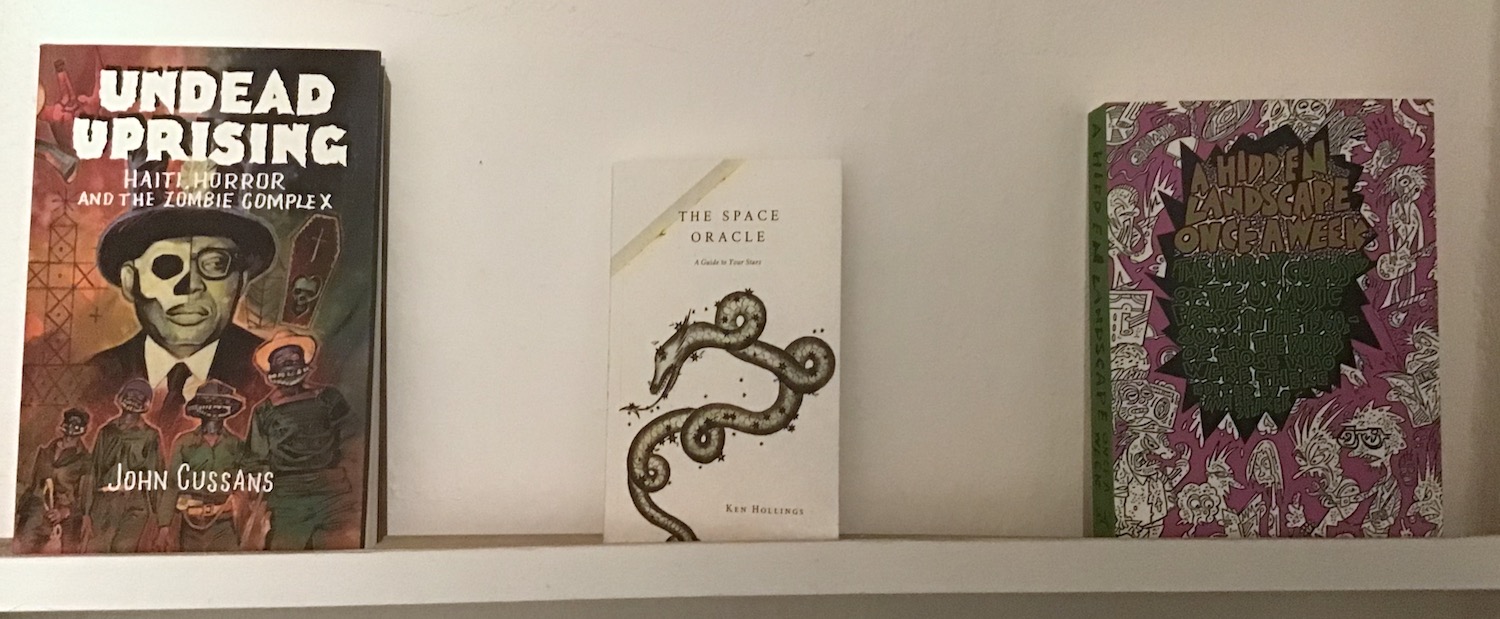

Bombed out in the war then neglected for decades, Shoreditch began to attract artists in the 1990s, and gentrified from there. Escalating prices have since pushed many artists further out. “It is the pits of London,” says Gate, who moved to the capital a decade ago. She only works in the area because she found a studio she loves — “our own little dungeon” — and can afford. It’s also home to Strange Attractor, a publisher specialized in occult subjects. Books on spiders’ webs and crop circles line the dark entrance corridor.

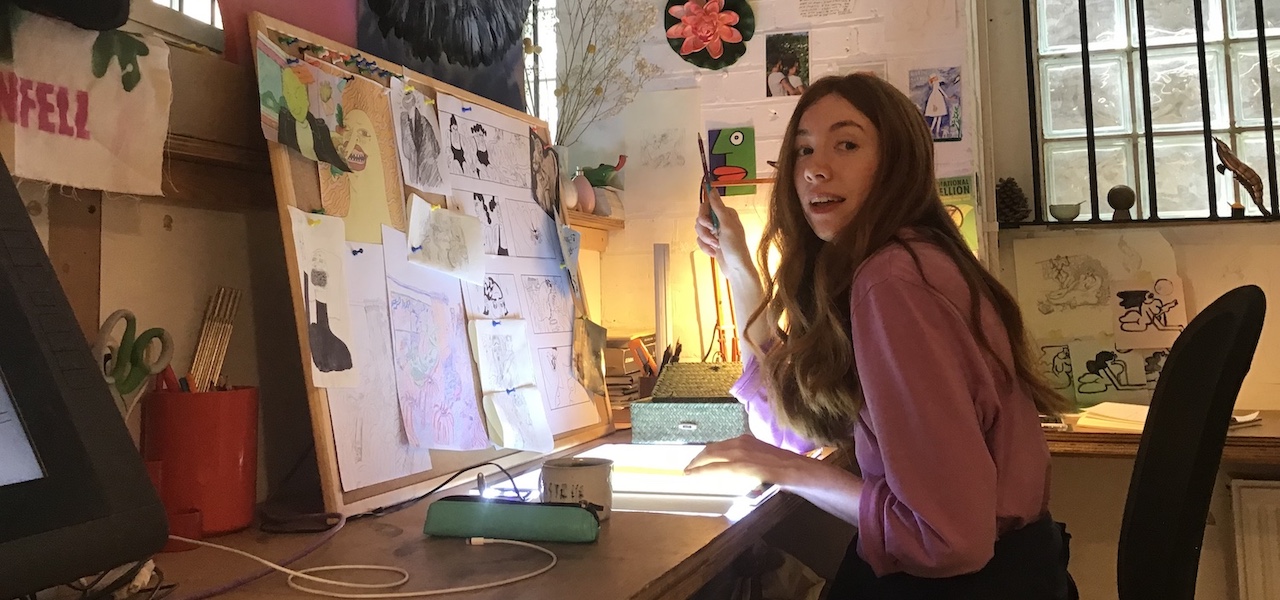

Gate shares her unit with the illustrator Rachel Sale, her friend and fellow Royal College of Art graduate. The space was previously unused — Gate noticed it while at a gig next door, and negotiated a cheap rent with the managers. “It looked like no one had been there for 30 years,” she says. You wouldn’t know it now: the space is snug and pretty orderly, its walls adorned with art and the odd flyer promoting a social cause. A glass-brick window lets in a weak light from the street. On the sill, an assortment of ornaments — a pine cone, a metal cast of a moth, etc. — bear witness to Gate’s stated passion for small objects.

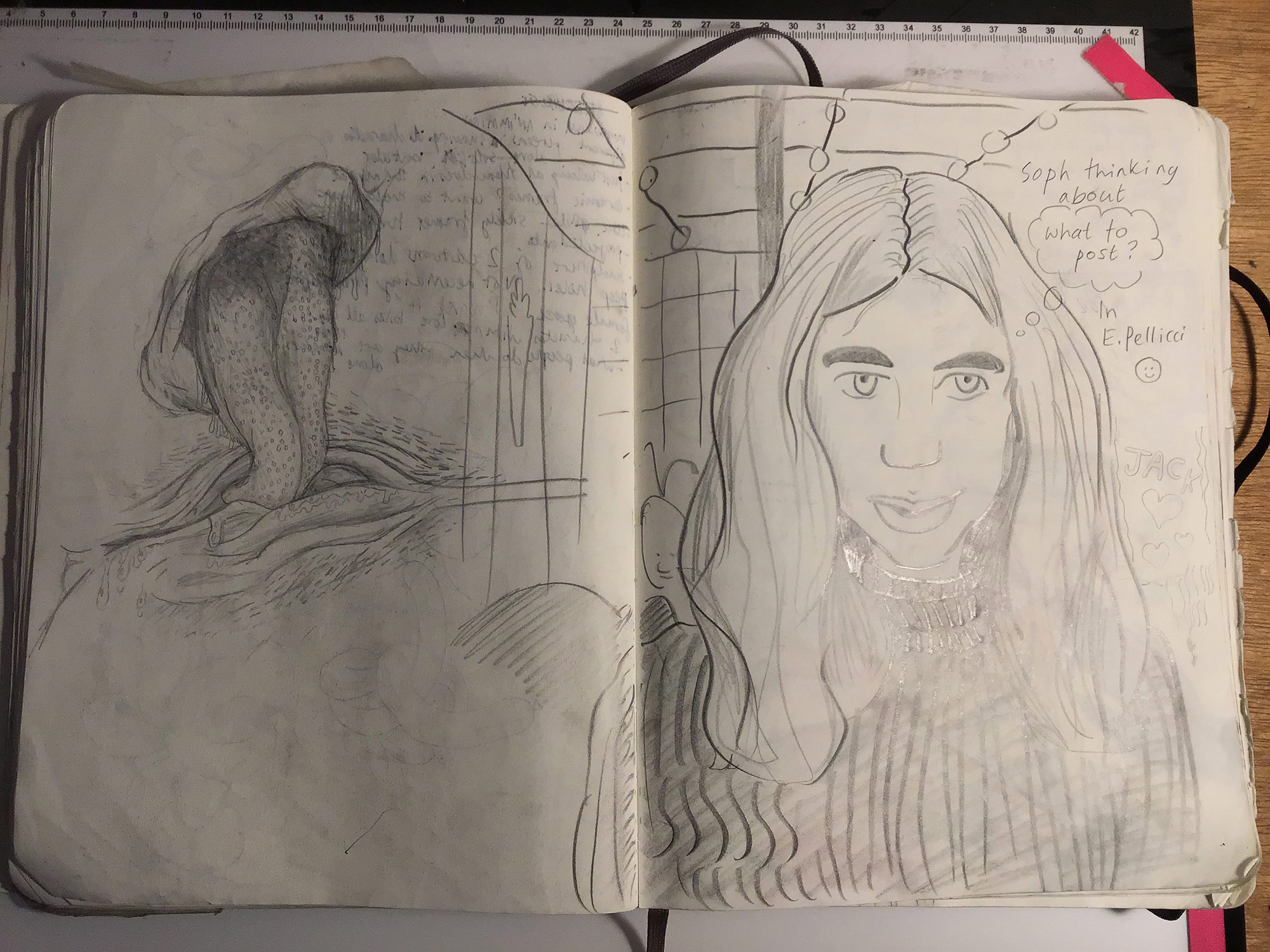

She doesn’t come here daily. During the early, conceptual stage of a project, she likes to do her thinking “wherever I happen to be”: in town, or one of London’s great Victorian cemeteries, or even the studio’s quiet vegetable garden, where she often goes to draw. She carries a large Moleskine sketchbook and mechanical pencil at all times. In her studio, she draws on a horizontal lightbox or her Wacom Cintiq 22HD tablet.

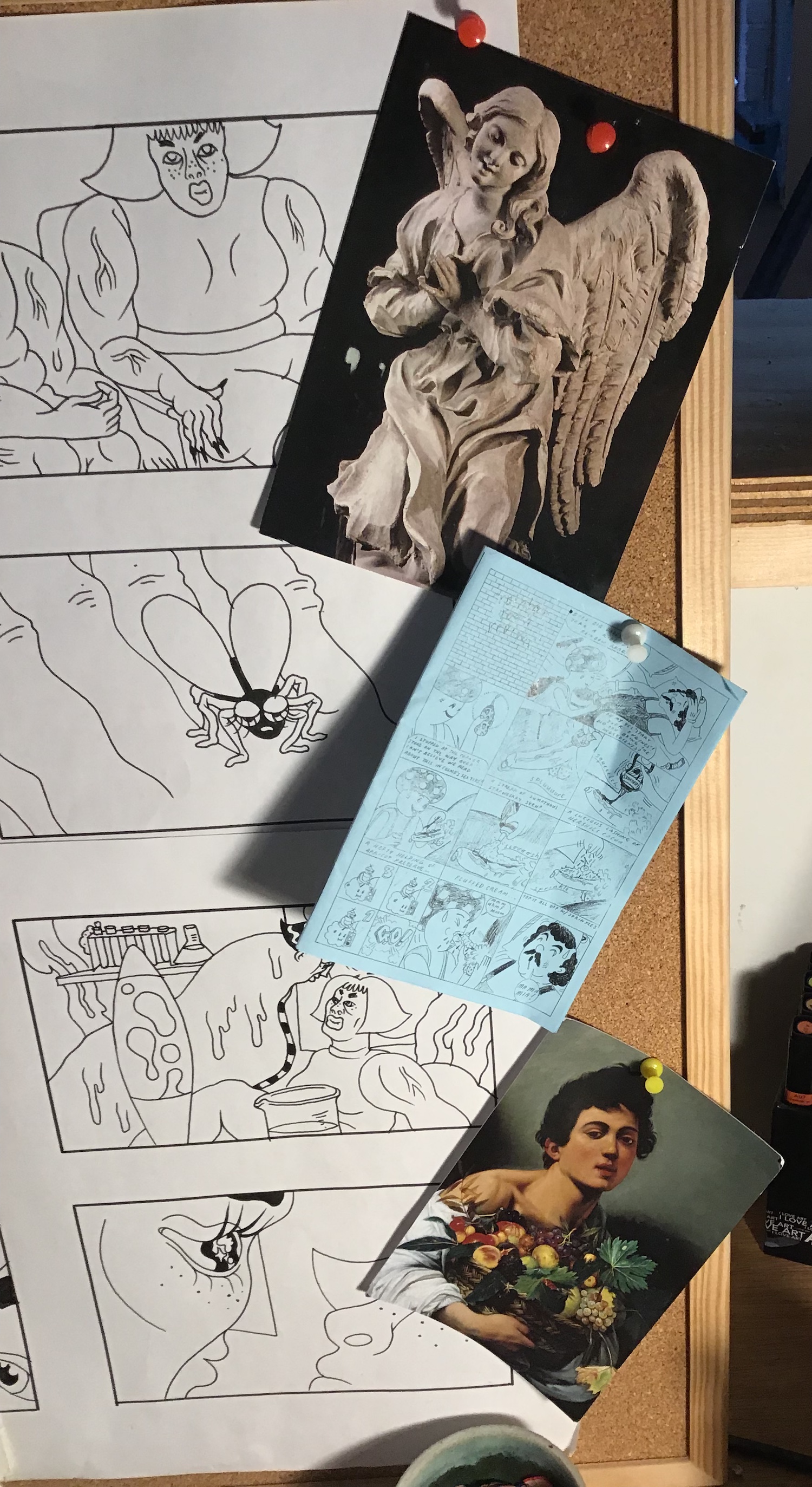

Marcy the long-nosed pervert; Caz and CC Jane the twin German rollerbladers: Gate’s characters reappear from film to film, their personalities and designs evolving gradually. They pop up again on the pages of her sketchbooks, and watch over Gate from the frames of a Slug Life storyboard that’s pinned above her desk. “Many animators create characters then dispose of them,” she says. “I’m interested in how they can grow with you, maybe like in Harry Potter.”

In the past, Gate has ditched storyboards in favor of comics, some of which she’s posted online. She sometimes makes loose animatics, but the process doesn’t come naturally to her: “I find it weird to cram all my ideas into a short space of time.” She designs and animates entirely in Photoshop. “The software is a little buggy at times and the files can get clunky, but there’s some wild shit you can do with all its funny features and a gnarly set of actions that you wouldn’t be able to do in TVPaint or Flash. Now you can download a nice plug-in called Animator’s Toolbar Pro that makes life a lot easier for animators.”

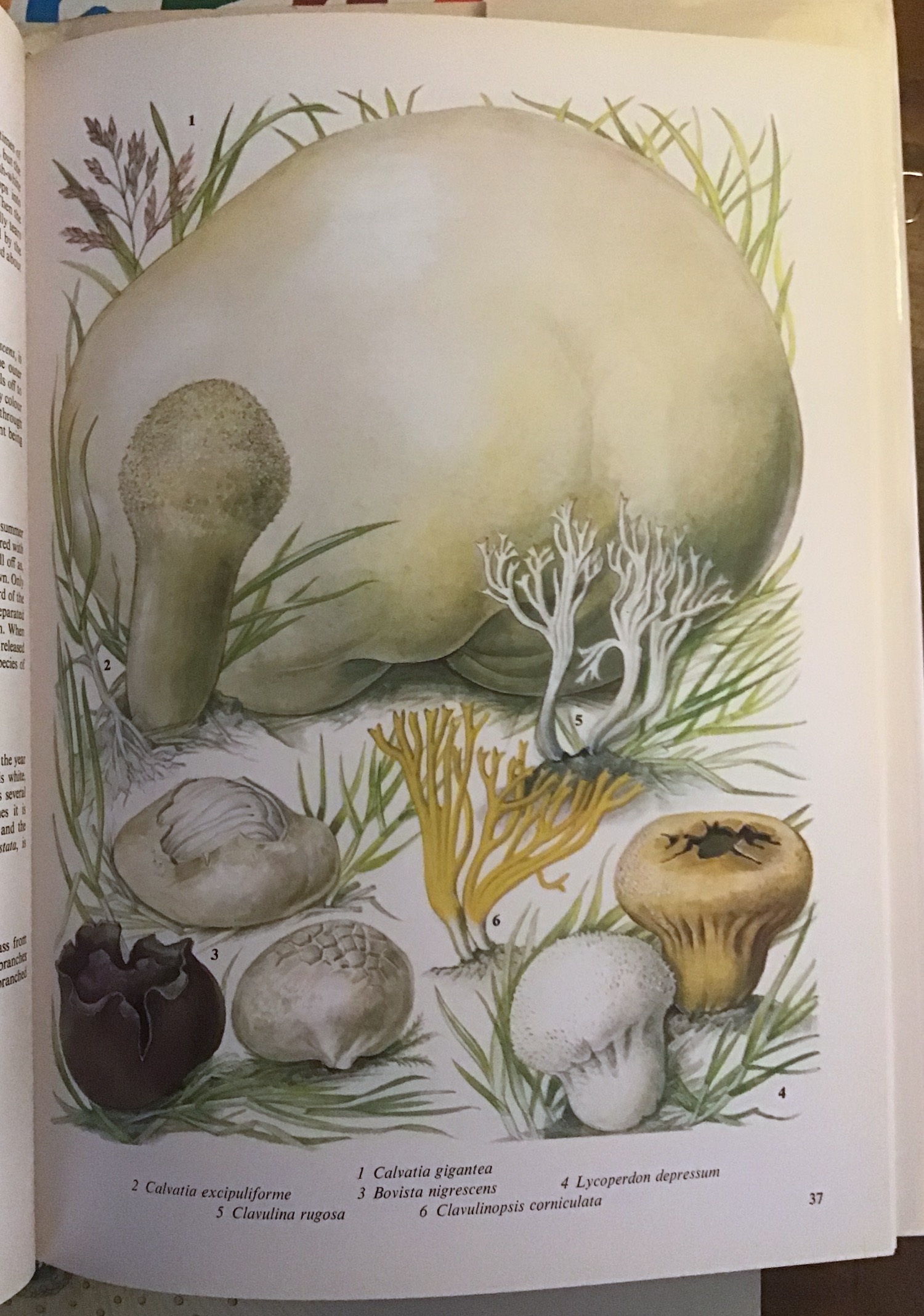

During breaks or moments of creative block, Gate turns to the bookshelf behind her. Tomes on modern sculptors lean against scientific reference books and compilations of optical illusions. She shows me paintings by the American artist Kenneth Price, whose use of shading influenced her, and exquisite drawings of plants by Barbara Nicholson, a botanical illustrator who happened to be her great-grandmother. Gate herself was briefly a resident artist at the Royal Institute of Science, and she remains hooked on science podcasts like Radiolab. I ask whether she studied real slugs while making Slug Life. Not exactly, she replies — but the production did coincide with a slug infestation in the studio.

Gate lists the animators she most admires: Sally Cruikshank, Bruce Bickford, Jan Svankmajer, David Daniels. I note that there’s a lot of stop motion in there, but Gate tells me she’s never really experimented with the medium. She pursued 2d animation in part because she saw it as more commercial — a crucial consideration for someone looking to make a living from her art. While her personal films are hardly mainstream, she’s managed to parlay her experience into a successful sideline in commissioned work for clients like Airbnb and The Guardian.

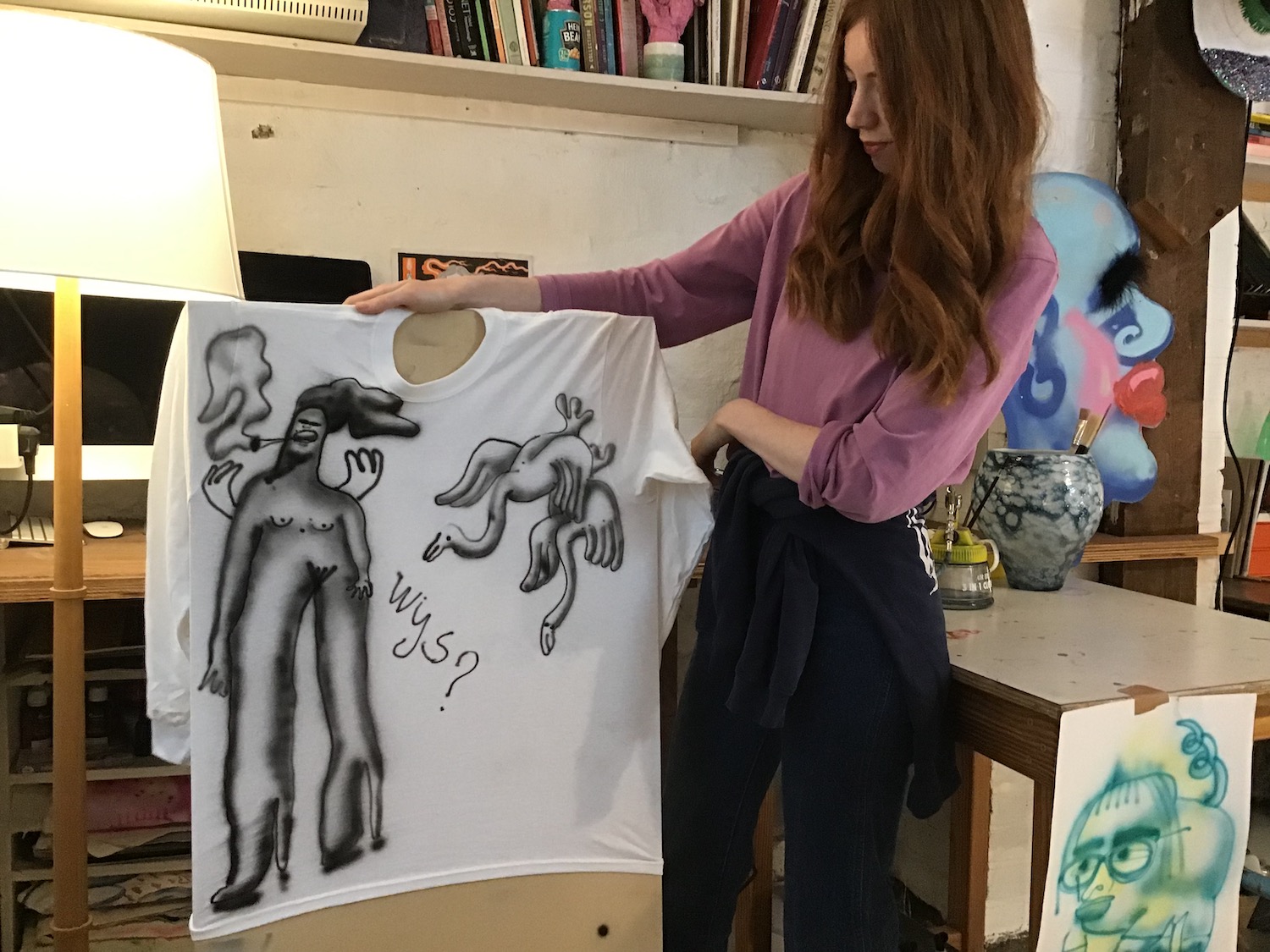

Even so, Gate is itching to try new approaches. She’s learning 3d software, and is applying for residencies to explore animation using one of her favorite tools: the airbrush. She has one in her studio, which she’s been employing to experiment with t-shirt design. On the spur of the moment, she takes a plain white t-shirt from a pile under her desk, airbrushes one of her characters onto it, and gifts it to me.

Lunchtime rolls around, and Gate takes me to a nearby bagel joint of local repute. This, along with her studio and a “post-apocalyptic park” around the corner, is the only place she likes in Shoreditch. Travel beckons: Slug Life won the FXX Elevation Award at this year’s GLAS Festival, netting Gate a $25,000 deal with FX Networks to develop and produce a short across London and New York. For now, though, she’s happy in the dungeon. “I feel comfortable and have my best mate working next to me,” she says. “I’ve got a good setup.”