Why Is It So Difficult to Make Cute Cartoon Characters?

Over on question-and-answer website Quora, someone posted a very simple question: Which is the cutest cartoon character ever created? The answers from Quora members cover a broad spectrum, some more obvious (Tweety, Pokemon, Pooh) and others less so (Gertie the Dinosaur, Night Fury from How to Train Your Dragon).

So what makes a cartoon character cute? You could reduce the answer down to a few basic characteristics: big eyes and head, fluffiness, warmth and chubbiness. “Cuteness is based on the basic proportions of a baby plus the expressions of shyness or coyness,” wrote Preston Blair in Advanced Animation. According to Blair, other cute traits include:

- Head large in relation to the body.

- Eyes spaced low on the head and usually wide and far apart.

- Fat legs, short and tapering down into small feet for type.

- Tummy bulges—looks well fed.

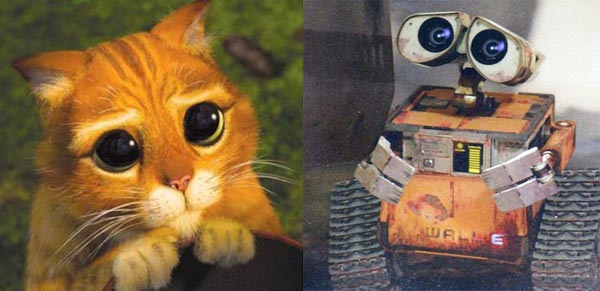

But cuteness is far more complex than even Blair’s set of rules; some consider E.T., Yoda and WALL·E to be the epitome of cute, despite their furless, odd appearances. Cuteness and a character’s perceived hugability aren’t always determined by aesthetic appeal. “Cuteness is distinct from beauty,” wrote Natalie Angier for The New York Times. “Beauty attracts admiration and demands a pedestal; cuteness attracts affection and demands a lap.”

In essence, any creature deemed cute is one that speaks to our nurturing instincts. The cuteness of an infant can motivate an adult to take care of it, even if the baby is not a blood relation. Even more, studies have found that humans transfer these same emotions to animals (or even inanimate objects) that bear our similar features. Finding Nemo combined all of these psychological elements perfectly—you can’t hug or cuddle a fish, yet adorable Nemo, with his fin damaged from birth and his human-like facial features, appeals to our caregiving instincts. In fact, every character in Pixar films, whether it’s a clownfish or a car, features forward-facing eyes, the most crucial feature for achieving an emotional connection with the audience.

But with any extreme comes another. If a character is too cute and sugary sweet, the audience can develop skepticism. “Cute cuts through all layers of meaning and says, ‘Let’s not worry about complexities, just love me,'” philosopher Denis Dutton told The New York Times. It is for that very reason cuteness stirs uneasiness and sometimes feels cheap.

After all, the adorable, smiling face of a child can hide the havoc he just wreaked by breaking all of his toys. “Cuteness thus coexists in a dynamic relationship with the perverse,” writes Daniel Harris in his book Cute, Quaint, Hungry And Romantic: The Aesthetics Of Consumerism. You could call this the Gremlin Effect—a character with an underlying creepiness. Troll dolls (which were recently acquired by DreamWorks Animation) and Cabbage Patch Kids are the inexplicable result of this paradox.

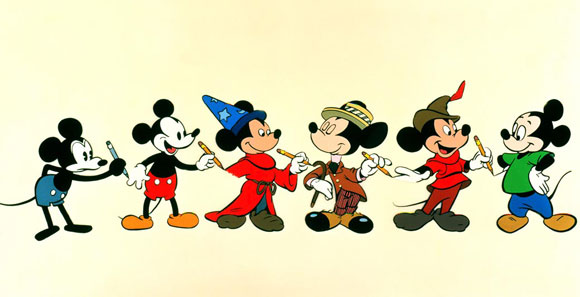

There’s no denying a cultural need to pigeonhole and perfect the attributes that could be popularly deemed cute. In his fantastic short essay on Mickey Mouse, biologist and historian Stephen Jay Gould asserts that Mickey’s changing appearance over time is a physical evolution that mirrors cultural attitudes toward cuteness. As the Benjamin Button of animated rodentia, Mickey’s eyes and head have grown larger, his arms and legs chubbier. Mickey has become more childlike and, most would say, more cute and less rat-like. Mickey isn’t the only character to undergo this transformation. The teddy bear, first sold in 1903, started out anatomically similar to a real bear, with a long snout and gangly arms. Today’s teddy bears more closely resemble the Care Bears, with pudgier features and colorful fur.

Audience don’t always need Mickey’s goofy grins and huge eyes to connect with a character’s cuteness. Pictoplasma, the artists’ network and conference that celebrates characters extracted from context, reveals how sometimes it’s our own invented narrative that blasts a character into hall-of-fame cuteness. As Pictoplasma co-founder Peter Thaler said explains, “It’s a horrible example, but Hello Kitty has no facial expression. You don’t know if she’s happy or sad; you just see these two dots. You’re projecting all the narration, the biography.”

Our ideals of cuteness continue to evolve, a trajectory in visual culture that has birthed Hello Kitty and Japan’s kawaii movement, Giga Pets, Furby, Elmo and Slimer. Often the most exciting, memorable cute characters are the ones who bear negative traits that reveal the vulnerability. Scrat, the saber-toothed squirrel from Ice Age, is adorable and loved by audiences even more for his greed. Cuteness, perhaps then, is not just about an objective set of physical features—it’s also about a behavior that compels audiences and connects us emotionally to the character.