It’s Time to Honor Don Lusk and Willis Pyle With A Winsor McCay Award

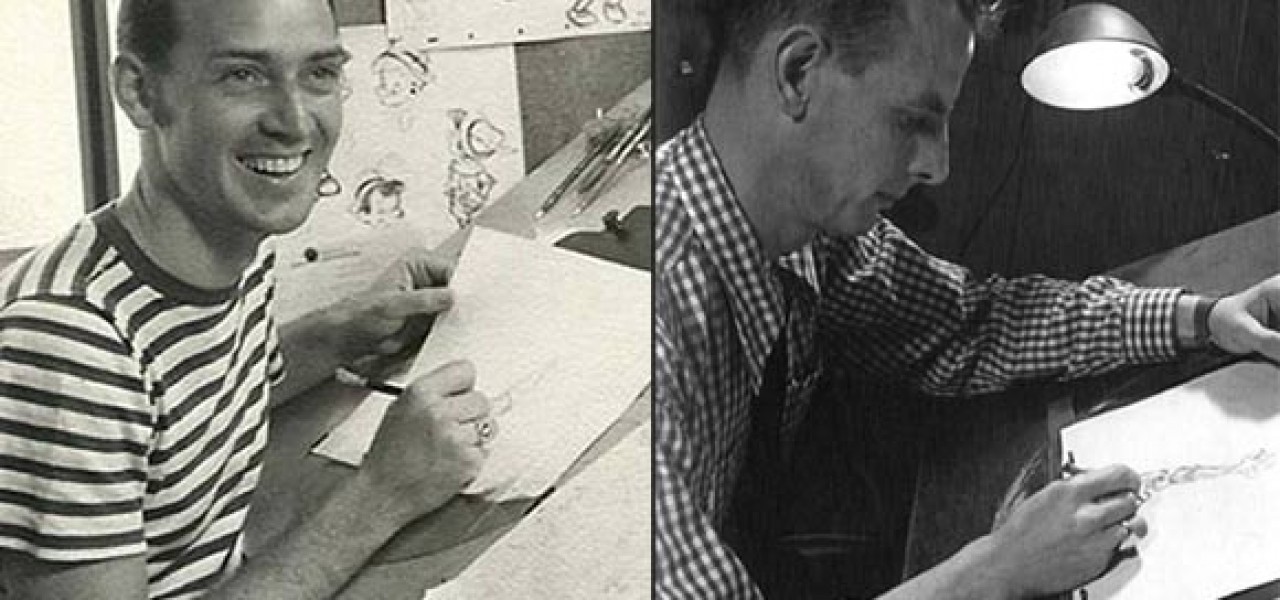

It’s a rare accomplishment to turn 101 years old, which is the age that animation legend Don Lusk turns today. But that’s only the latest milestone in a career filled with them.

Mr. Lusk’s animation career began at Disney in 1933, and with the exception of a time out for the Disney strike and WWII military service in the early-1940s, Lusk worked there continuously until 1960. Of the seventeen animated features made by Disney from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to 101 Dalmatians, he was an animator on 13 of them. He animated Cleo and Figaro in Pinocchio, the Arabian Fish Dance in the “Nutracker Suite” of Fantasia, the title character in Alice in Wonderland, and Wendy in Peter Pan, to name but a few.

That would constitute a remarkable career for anyone, but Mr. Lusk was just getting started. After his Disney years, he continued working for another thirty years or so in both feature and television animation, filling out his resume with at least ten Peanuts specials, features like Gay Purr-ee, and hundreds of episodes of Saturday morning Hanna-Barbera cartoons. He finally retired from animation in the early-1990s as he approached the age of 80.

Despite Mr. Lusk’s achievements, the ASIFA-Hollywood organization has continued to overlook his contributions to the art form when it’s time to present their annual Winsor McCay Award. The McCay awards, for those who may be unfamiliar, were initiated in the early-1970s to honor “career contributions in the art of animation” and are currently presented annually during the organization’s Annie Awards.

In recent years, ASIFA-Hollywood seems to have forgotten the mission of its own award. While 101-year-old Don Lusk, and fellow Disney and UPA animator, Mr. Willis Pyle, who just turned 100 a couple months ago, continue to be overlooked, much younger artists with contemporary pedigrees have begun to recieve the award.

The change began in 2006 when, in a boost to bid the film industry’s acceptance of the Annie Awards, ASIFA-Hollywood began courting “celebrity” artists instead of the rank-and-file veterans of the Golden Age. That year, a 36-year-old Genndy Tartakovsky won the Winsor McCay for lifetime achievement. (For comparison, one year earlier, the average age of the three recipients had been 81 years old.) Ever since 2006, the majority of the Winsor McCay recipients have been mid-career, and only a handful above the age of 65. Even creative people who aren’t especially known for their animation careers, like Ronald Searle and Steven Spielberg, have received the Winsor McCay over artists who worked for fifty-plus years in animation.

It would be unfair to conclude that ASIFA-Hollywood doesn’t care. The people running the organization are a savvy group who understand animation history; they’d be unlikely to argue the merits of honoring Mr. Lusk and Mr. Pyle with a Winsor McCay award. But the organization’s thirst for general film industry legitimacy has blinded them to the original noble purpose of the Winsor McCay Awards.

Perhaps it’s best to remember that animation has never been about celebrities. Drop a well known animator in the middle of Kansas, and they’ll be as anonymous as the next person. ASIFA-Hollywood acknowledged that basic fact for the first three decades or so of handing out the Winsor McCay awards. It earned its reputation as a gutsy organization within the film community, honoring the great artists it knew needed to be honored instead of the artists that might elevate its standing a rung or two on the film industry ladder.

In a time when the word “legend” is flaunted around indiscriminately, we can say with absolute certainty that 101-year-old Don Lusk and 100-year-old Willis Pyle are worthy of the label. Let’s hope ASIFA-Hollywood gives them their due while they’re both still with us.

.png)