Oscar-Winning Producer Nicolas Schmerkin Explains How To Build Relationships With Directors

Last December, at Les Sommets du cinéma d’animation in Montreal, I attended a panel discussion about the production of animated shorts. The focus was on producers who have enjoyed longstanding partnerships with individual directors. Nicolas Schmerkin was among the panelists, and in discussing his career he kept returning a metaphor: the relationship between producer and director is like a marriage.

Intimacy is key to Schmerkin’s working habits. He spoke of getting drunk with his directors, collaborating closely on the creative process, and fighting when things go badly. His remarks were quite different from the language of professional distance that other producers in the room were using. This is one reason why they struck me.

Another is that his approach clearly works. As the director of the Paris-based Autour de Minuit, Schmerkin is one of the most prominent producer-distributors on Europe’s indie animation scene. A few children’s series notwithstanding, he specializes in shorts with edge and character. His tastes have led to multi-film collaborations with such distinctive directors as Chris Shepherd, Alberto Vazquez, Donato Sansone, and the late Rosto (whose early films inspired Schmerkin to become a producer). In 2010, he won an Oscar for Logorama, a bracing satire of consumerism.

After the panel discussion, I wanted to hear more. We continued to speak about what it takes for a producer to build a successful working relationship with a director. The following seven insights are culled from our email correspondence, and interspersed with comments he made in Montreal. They have been translated from French.

1. When getting to know a director, get drunk together.

Schmerkin: To produce a director, you need to like them, as well as their work. These are necessary and sufficient conditions to start talking. I want to work with people who are talented, but who can also bring something human to the relationship. Usually, I become interested in a director when I fall in love with their film (in a festival or, more rarely, online). As we are also distributors, another stepping stone to producing a director is to distribute one of their existing films.

2. Every director is different.

Schmerkin: Not only that, every production with one director is also different. So you have to know how to adapt to each personality and each project. Some directors want no direct interference from the producer or anyone else, while others require collaboration. Some want regular feedback, and others prefer to work alone and only show you things once they’re finished. When there are several co-directors, sometimes they first exchange doubts, comments, and feedback among themselves, and present things to the producer once they’re already well thought through.

In all cases, I keep prodding them as long as I still have things to say, and haven’t tried every last way to convince them of my opinions. After that, it’s up to them what they do with my comments.

3. As a producer, you can have creative input.

Schmerkin: When I feel that I can bring something, drawing on my intuition and experience (I wrote and edited films before entering production), I suggest it to the director, who can accept it or not. If they don’t want me to get involved, I respect that. But if I’ve made a suggestion, it’s because I feel that some things need to change — so I’d then propose bringing an outside writer or editor, someone neutral, onboard. Filmmaking is a team sport, and animation even more so. I can’t work with directors who believe they’re right about everything and listen to no one.

4. A producer and a director are like a couple.

Schmerkin: I see them as parents who have to give birth to a child: the film. You have to start with a shared goal and similar ways of seeing things. Along the way, you may fight; if the fighting gets too intense, you may split up during production, like a couple, and either the producer or the director will leave the project. The other will have the ultimate responsibility to complete it.

If everything goes well, the parents give birth to a film of which they’re often equally proud, and which they’ll go defend out in the world. If you enter into a paternal or maternal relationship with the director (because they want that, consciously or not), things can get distorted and may result in an unnatural birth. Film production is a partnership, not a tutorage.

5. At the outset, tell the director, “I’m going to annoy you.”

Schmerkin: I don’t think you can do harm by being too frank. On the other hand, you can cause damage by not being frank. But you need to know how to say things that are constructive for the film and the director without hurting or upsetting them. Again, if you see it in terms of being a couple, it serves you well to be frank, for the greater good. [On the other hand,] in a parent-child relationship there will always be lies, rebellion, a bit of an Oedipus thing.

6. Don’t start producing a director you’re already friends with.

Schmerkin: A short can take up to five or six years to make, and the working relationship during that time, with its potential conflicts, can spoil your friendship. It doesn’t always happen, but when a conflict arises in the course of production, you risk losing both a director and a friend. That said, most directors I’ve worked with subsequently became friends — some of them very close ones, like Rosto.

7. One successful collaboration doesn’t guarantee another.

Schmerkin: Sometimes, you produce with a director, and it’s a nice human experience that leads to a good film, but the next project they pitch to you is less convincing. At this point, you can either pass or interrogate the director about why they want to do the project, why it needs to be made. I don’t like directors who repeat themselves — I like to be surprised, and I suppose most viewers do too.

Very occasionally, I’ve worked with a filmmaker on a project they were dead set on doing in a certain way, even though I wasn’t fully convinced. I did it with a view to sticking with the director throughout their career, and supporting them, given that they needed this new film to be produced in order to make a living.

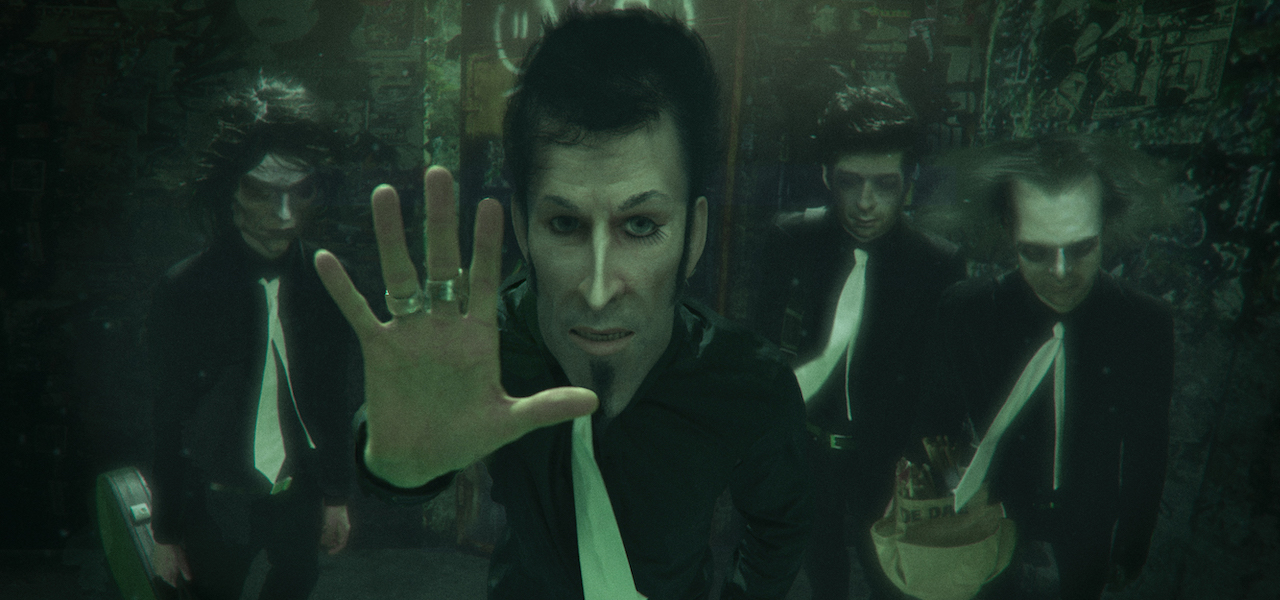

(Image at top: “Logorama” by François Alaux, Hervé de Crécy, and Ludovic Houplain, produced by Autour de Minuit, H5, Addict, Mikros Images, and Arcadi.)