Will Wes Anderson’s ‘Isle of Dogs’ Help Animation Be Viewed As A Serious Artform?

Last Thursday Wes Anderson’s latest movie – the stop-motion animated Isle of Dogs – premiered at the prestigious Berlinale Film Festival in Germany. It marked the very first time in 68 editions that the festival chose to open with an animated film.

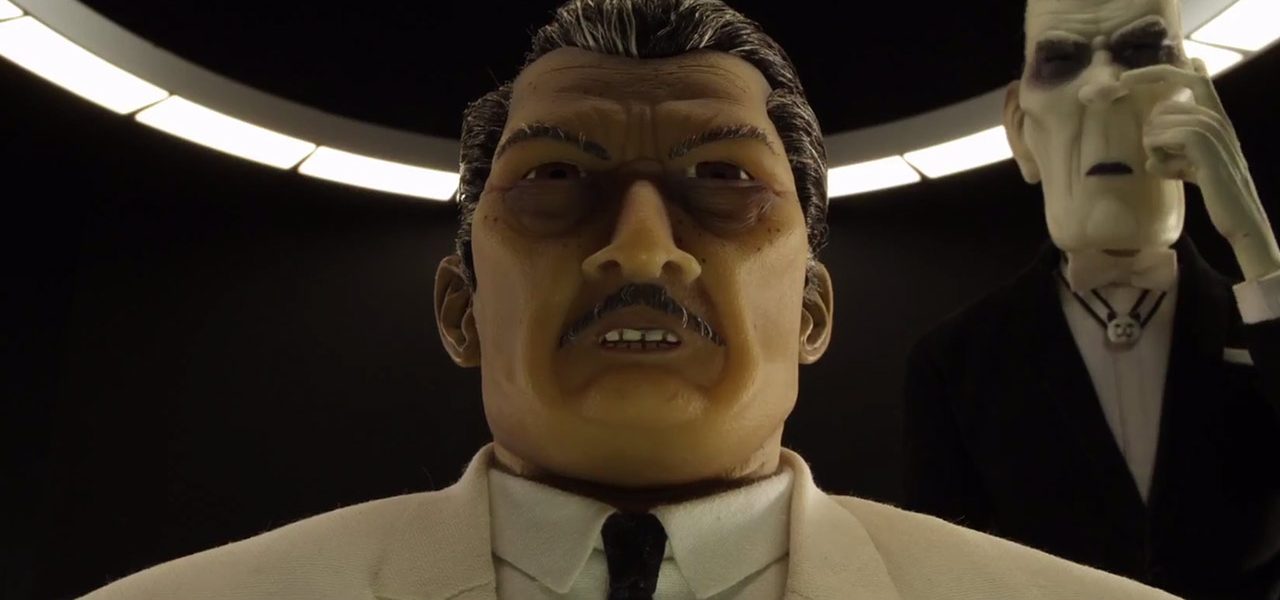

At the invitation of Fox Searchlight Pictures (all-expenses-paid), Cartoon Brew traveled to Berlin to see the film. Isle of Dogs thankfully lives up to the promise of its trailer and clips that have been released thus far – it is a wonderful looking and captivating adventure that should fare well with both Anderson and animation fans alike, showcasing exquisite animation and cinematography, and fun pacing and jokes. Anderson visibly dives into and experiments with the medium of stop-motion animation, more so than in his previous Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009).

Early reactions from Berlin audiences and American film press towards the Isle of Dogs has been overwhelmingly positive. Described by critics as “richly imagined” (Variety), a “hugely enjoyable package” (The Guardian) and a “stop-motion stunner” (IndieWire), it’s great to see an animated feature film praised so highly. Reading on through though, I couldn’t help but notice the lack of vocabulary that the live-action film critics have when discussing animation.

Take for example, some of these quotes: “Kudos to the film’s animators too, because sometimes they really capture something of the behaviour of dogs.” That was Screen Anarchy. Other highlights refer to the film as “this new talking-animal entertainment” and “the genre-defying fable”. Thanks, The Guardian and New York Times. And Screen Anarchy jumps in again, with their inventive referral “an ultimate bedtime reading experience.”

How many times should we remind the live-action world that animation doesn’t automatically make a film for kids (Isle of Dogs is rated PG-13); that animators add as much (or more) than a voice actor to the success of a character’s performance (which are nicely expressive yet stylized in Isle of Dogs); and that animation is a medium, a technique, a storytelling form – not a genre?

When I spent the Berlinale festival hanging out with other journalists – mainly ones from the live-action field – it struck me that they didn’t mention ‘animation’ once, when I asked them what they thought of Isle of Dogs. I figured it’s a positive thing – that form or technique doesn’t matter to them. But reading the online reviews changed my mind.

For animation directors, but really for all animation professionals, it’s important to openly express, as much as possible, all the qualities that animation has. If we want animation to be respected, there’s no room for false modesty. This should be obvious, but animation is an intrinsic part of an animated film’s artistic success. In the case of Isle of Dogs, the design and stylization of the movement is a big part of why its slim storyline works beautifully as a rich metaphor, why despite its extreme symmetry (even more extreme than in Anderson’s other films) the film’s world and characters feel alive and full of character and emotion, and how it can feel so timeless.

While it would be foolish to think Isle of Dogs is going to change the many preconceptions around animation overnight, the movie undoubtedly creates a soft opening for progress. Press and festival attendees both praised the film’s dark political allegory, the emotional resonance that the puppets achieved, and the craftsmanship that went into stop-motion animation.

When it comes to praising the craft of stop-motion, Anderson himself took the chance whenever possible at the film’s speaking occasions in Berlin. Recalling how mesmerized he gets by watching stop-motion animators doing their work, the filmmaker lauded in a panel, “it’s like muscle memory in ultra slow-motion.”

At the festival’s press conference, Anderson also spared no time referencing animated works that inspired him. He credited Miyazaki for inspiring Isle of Dog’s “detail and also the silences,” further stating that the Japanese director harbors “a kind of rhythm that’s not in the American animation tradition so much.” Anderson also threw in some Chuck Jones and Tex Avery mentions during the press conference, when talking about classic cartoon tropes like the use of clouds of dust to visualize a fight. Other animated works he referenced include The Plague Dogs (1982) (“although our film is much more cheerful”) 101 Dalmatians (1961) (“one of my favorites of the Disney [films]”), Lady and the Tramp (1955), and Watership Down (1978).

When high-profile directors like Anderson voice their appreciation for the art of animation, and as more feature-length animation for grown-ups actually finds its way to the spotlight, hopefully critics will learn to praise where praise is due, and audiences will discover the animated film’s wonderfully rich palette of possibilities.

Isle of Dogs competes in the Berlinale festival’s competition, but despite its high quality and positive response, its chances of winning are slight. History tells us animated films don’t beat out live-action films in competitions – they seem to be stamped ‘less good’ by definition. In the unlikely case that Isle of Dogs wins the festival’s grand prize, it will be because it’s ‘a great Wes Anderson film that happens to be animated’, not ‘a great animated film.’ Nevertheless, every small step towards a more accurate notion of animation’s richness is a positive and welcome development.

Isle of Dogs opens in U.S. cinemas on March 23, followed by its international rollout.