‘Who Framed Roger Rabbit’ Hits 30: A Look Back At ILM’s Astonishing Old-School Optical VFX

The production of Robert Zemeckis’ Who Framed Roger Rabbit – celebrating its 30th release anniversary on June 22 – required the melding together of the then-latest in animation and effects technologies.

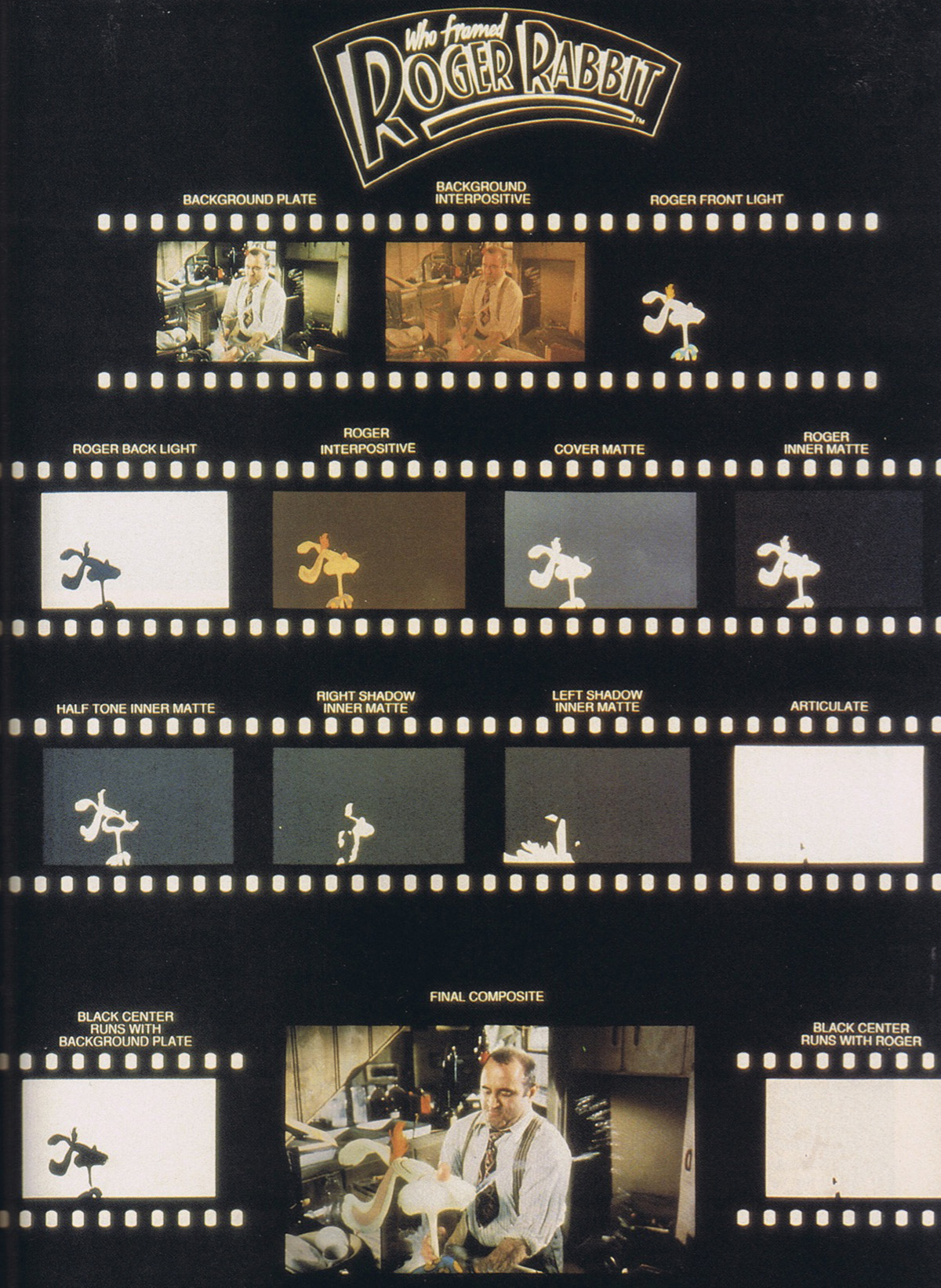

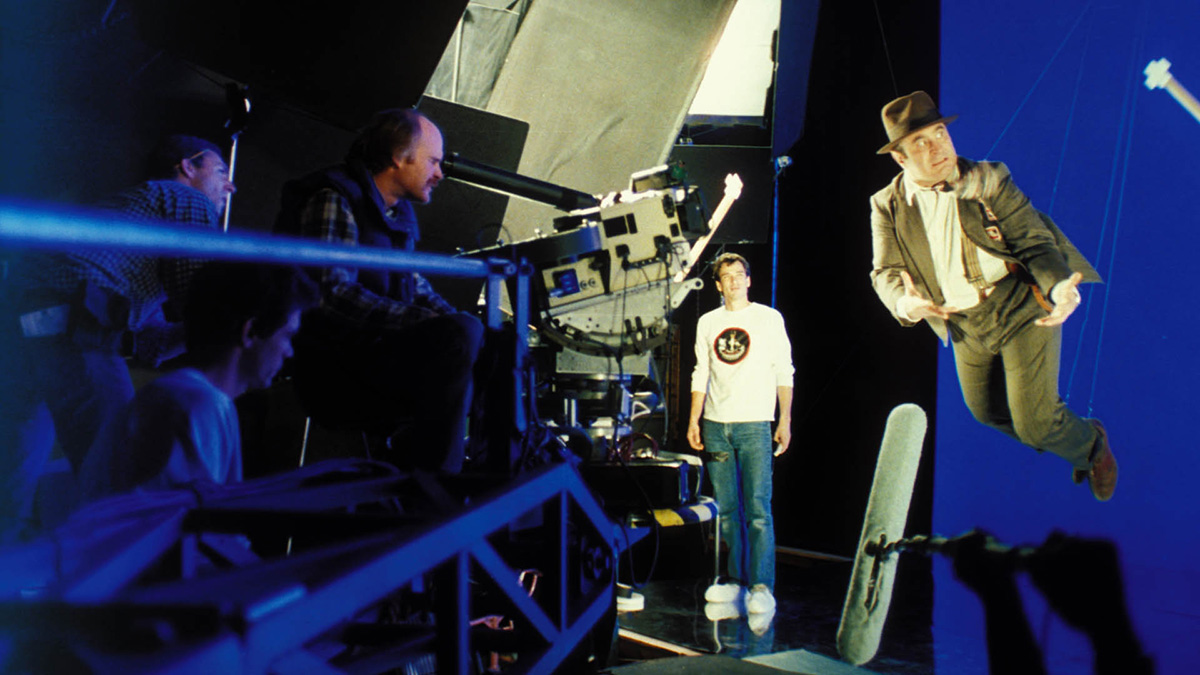

On set, practical gags and even robots helped ensure actor integration and eyelines would match the 2d characters that would later be animated by a team led by animation director Richard Williams. Their work, which included not only principal character animation but also drawn highlight, shadow, and other ‘passes’ – designed to give the characters more dimension – would be optically composited by Industrial Light & Magic (ILM).

ILM’s job on the film was intense. More than 1,000 shots went through their optical printers; these days, of course, such a task would be done with digital compositing. The film would ultimately win the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects (awarded to Ken Ralston, Richard Williams, Ed Jones, and George Gibbs), while Williams additionally received a Special Achievement Award from the Academy. To find out more about just what the old-school compositing process required, Cartoon Brew re-visited ILM’s complicated work with the optical photography supervisor on the film, Ed Jones.

Cartoon Brew: What did your role as optical photography supervisor at ILM on Roger Rabbit involve?

Ed Jones: The responsibility of optical photography is very much like building a sandwich at a deli. It’s taking all the various elements that have been shot and compiling them into something that’s seamless for every frame, for 24 frames a second. You’re re-photographing elements. You’re using a lot of optical printers that have two projectors and a camera, and you’re having to make what we used to call holdout mattes to create a void, where you would then put an image. In doing that, you have to figure out all the frame counts – the counts, the beats, the exposures, the fade-ins, the fade-outs, et cetera, to make this illusion come to life on the big screen. Take Jessica Rabbit: for example just to create her dress, her look, and all, had 30 different pieces of film. It all had to come together synchronously to make her look like she’s in the scene with Bob Hoskins (Eddie Valiant).

Can you briefly outline all of the steps required to make the animated characters interact with the live-action actors?

Ed Jones: We’d shoot original photography on VistaVision plates which gave you a lot more area of film to work on. You take those and you do your selects through editorial. Those selects then would go through a process called photo-roto, where we would actually send those to Disney, and the rotoscopers would shoot a black and white photo of each frame on this oversized paper. It was pegged on the animator’s desk back in London, and they would animate to that. The animated action that Richard Williams’ crew came up with was dictated from the on-set performance. Once that performance was dictated, the tone mattes, which were effectively effects animation, would be created. And then they would send the base animation and then all these other things back to us, and we would create the characters.

Then what was the process back at ILM of bringing all those elements together?

Ed Jones: We’d look down and say, ‘How, if we were to photograph this…’ – it’s almost like taking a cg model these days and doing a turn table – ‘if we were to photograph it, where would the shadows be, or where would there be rim lights, or with Jessica, say, how many layers of sparkles would she have?’

And then those tone mattes would be created as ‘voids’ – just a shape that would fit on top of the character. They would then be sent to the optical department, and then what we created was what we called two-and-a-half-D, and then we used those tone mattes and used color print film, and created a pallet of almost 350 colors that were on top of the primary colors that we would then use with diffusion to shape each one of those characters. And that’s where there could be two tone mattes, or there could be 30, just depending on the character.

And so that became a way of introducing that two-and-a-half-D look that allowed us to blend them into the scene. Of course, you had wonderful practical effects, like Roger running his hand across the desk, and all of a sudden they’d be moving the dust, or using a gun on a rod in the water and then putting animation over the top of it, whatever it might be. It was a significant effort by the on-set puppeteers, especially the way that they puppeteered things underneath the stages.

Like, in the club, look out for some of the great work by the puppeteers laying on their backs with small monitors, moving around trays. You see the plate, you just see that there’s a bunch of serving trays. What the hell’s going on? And then the next thing you know, we’re putting penguins by each one of those. So, a lot of complexity, and the tone mattes, allowed us to create that 3d effect that, actually, for several years afterwards became the ‘rabbit-ification’ of Madison Avenue, because they started using that in commercials, the same technique, except doing it in bad video resolution.

What was the optical printing department like? Was it more than one optical printer? How did things actually come through the department?

Ed Jones: Well, from the compositing point of view, you needed an optical printer that had two projectors, for the most part, in this particular instance, two projectors and a camera. But for us, we also had to create elements, whether they were black and white elements or not, whether it was through a bi-pack situation, or whether it was through projector. I think we had something like a total of seven printers.

And so all of those were used in a creative manufacturing type of way, where you’re building a car back in the day, or even today, you build the seats, the different elements that go into the actual car itself, and it rolls off the finish line. Well, think of this as that — we had to build all these individual elements, on workhorse printers. Some shots would just be one on one bi-packing the camera to a camera negative, to another element, and replicating it, and flipping a matte from positive to negative so that we could use that space in a different way within the way we build the composites.

And then we had to manipulate those pieces of original art into different, other pieces of film, then assemble the pieces of film, like a large jigsaw puzzle, so that they run synchronously, frame by frame, to give you the effect that you want, whether it was the tone matte and seven tones on Roger, or whether it was holding Roger out over a background. Or Jessica taking a handkerchief out of someone’s hand in the club, and passing it to herself, that type of thing with rotoscope and articulated mattes.

It was a very creative process, but also very much of a manufacturing process, because you also have to describe each one of those units, those printers. For each element you’re creating, you have to call the exposure out, which you had to figure out, which was called wedging, where we’d do a whole exposure chart, from dark to light, two-and-a-half stops one way or another. Somewhere around there in the different neutral density filters, like a 10-stop ND would equal a third of a stop, and we’d have to figure that out, which is base photography if you want, besides camera photography. So it became formulaic, manufacturing creative illusions.

Were those printers running around the clock? What was the environment like as you were in full scale production?

Ed Jones: We were doing Who Framed Roger Rabbit with the animators in London, and the team shooting live action in London. We were also doing at the optical department, at the same time, Willow, and then Empire of the Sun. There were a couple conversations where some people would say, ‘Well, you need to take a day off,’ and I’d say, ‘Well, I’ll take a day off when I’m tired.’

But I don’t know that there was a more enjoyable time especially with Roger Rabbit, and sitting in dailies every morning, and being critical to our work, but laughing at the same time because of the performances that we were actually monitoring, watching. I consider that time really as a bridge into large volume visual effects production, because no one had done that many effects shots before in the time that we had to do it, for three different movies.

Was there any digital compositing or digital fixing, or anything like that considered for Roger Rabbit?

Ed Jones: Nope. There wasn’t. You know, I mean, around that same time, you might have had the introduction of digital compositing. I mean, Young Sherlock Holmes came out, and there’s some effects shots there that we did as Pixar, when it was kind of still part of ILM. I mean, the next step was, a couple years later on Hook, where we actually took Photoshop and mattes, and would composite with those digital tools, but we didn’t have enough render power! They would have to do one frame first on one matte, second frame on another matte, third frame, and then it’d all come together.

With digital, you can go in and fix almost anything, but how did you deal with re-dos on Roger Rabbit?

Ed Jones: Well, there were always re-dos. I mean, our goal was a ‘take one’ final, and basically that would be the equivalent to a dunk in basketball, or touchdown in a sports analogy. But there wasn’t a great amount of take one finals because there was always an exposure here or there that was off, and then you’d have to tweak it. So you built it from a baseline up, and the changes would be, ‘Well, he’s too red in this area,’ or whatever the color comments were.

Or, ‘There’s a matte line from these frames, from that frame,’ and you had to re-do your mattes and shrink your mattes through black and white processing, and different tricks that we created and used. So the repetition was fast and furious. I mean, you know you had to maintain inventory out the door as fast as you could, and had to maintain inventory in the door to get it done in a timely way. So with this we just had a process, we’d turn it over and over.

Once you get started, the way that each scene started was to take a hero shot, either one or two. Let’s just say there was 20 shots in a scene. We’d take those one or two and come up with the base recipe as far as the tonality, the color, and how it’s working within the blends, as far as any blurring, or mattes, or anything like that, as far as the edge characteristics. We’d establish those, and everyone would sign off and say, ‘Yeah, that would look great if we could do the whole scene that way.’ And then from there you try to match to all those hero shots.