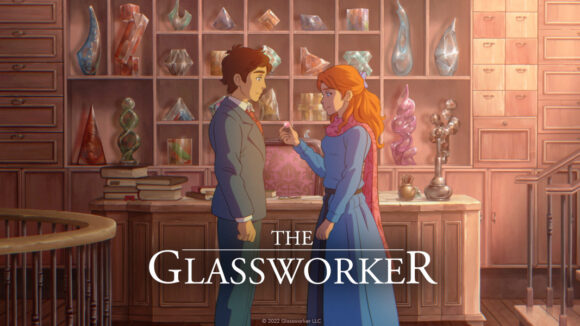

Meet The Team Making Pakistan’s First Traditionally Animated Feature ‘The Glassworker’ – Video Exclusive

“I’m ready to go to the ends of the earth to make this happen.” When these words come out of Usman Riaz’s mouth, you know he means it. Riaz is the director of The Glassworker, Pakistan’s first traditionally animated 2d feature and the co-founder of Mano Animation, a studio that he and his team have built from scratch in order to make their dream come true.

During Annecy this year, Cartoon Brew sat down to discuss their journey so far, what inspires them, the challenges of setting up a studio in Pakistan, their profound perseverance, and how close they are to finishing the film.

The full conversation can be seen here:

Looking through the art that has been released from The Glassworker so far, Studio Ghibli’s influence on the project is clear. As Usman mentions in the interview, “Studio Ghibli is a huge inspiration. They are my heroes.” In fact, Riaz owns many of the art books released for Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata’s features. “I learned so many things about film making from them,” he says.

Similar to the method used by Miyazaki himself, Riaz drew all the storyboards for The Glassworker. Although, he is quick to explain, “I am no Hayao Miyazaki or Mamoru Hosoda… they are masters of their craft. While I did draw the whole storyboard myself, we did have a script.”

As a means of demonstrating what they have been able to accomplish so far, Mano Animation has given Cartoon Brew exclusive access to the film’s show reel, which was screened for the first time during the work-in-progress session preceding our conversation with the team.

Discussing how he prioritizes story, Riaz describes his seeded belief in wanting to get every part of this film right. “Story is key. I love animation. I love the craft, but if the story is hollow behind the animation then you just have a bunch of pretty pictures.”

While creating a rich, original story is one thing, setting up a studio that deals almost exclusively in traditional animation methods in a country with no historical tradition in the artform is something else entirely.

To that end, Riaz asked the people closest to him to join in the venture, including recruiting his cousin Khizer Riaz as producer and his childhood friend Mariam Paracha as art director. Both share his vision.

Paracha explains, “Usman has a tendency to get people in and not let go.” Together, they launched the studio and began figuring out what they needed to do to create an animated feature.

Khizer recalls, “We had to figure out everything ourselves. [Usman] taught himself how to storyboard, Aamir – our animation director – reverse engineered how to do the animation. Production did the same.”

Attracting talent to work on 2d animation in Pakistan wasn’t straightforward either. Traditional animation is a tough, highly skilled area of work, and the Mano Animation crew were surprised when a call for artists drew replies from doctors and dentists willing to switch from their established careers in order to work on the film.

While the response from those professionals was remarkable, often the greatest challenge was convincing their parents that a career in animation is possible in Pakistan. Usman recalls that, “We sometimes spent days at the studio with parents coming in and assessing what we were doing, seeing if it was worthwhile for their kids to venture off and try. It’s very difficult to ask that of someone. Your child has a successful trajectory, and we’re asking them to abandon that.”

The passion that Riaz and his team displayed to the parents was what eventually persuaded many to allow their children to join the studio. As Usman recalls, “One of the dentists’ fathers was in the studio and was constantly arguing with us that this is not a good idea. We were trying to convince him saying, ‘But it is, and your child is very talented; please let her pursue her dream and let her come and work in the studio.’ After about a day of discussion with Khizer, Mariam, and myself, he walked out and told his daughter, ‘You know these guys? They look so crazy, and they are so crazy about this craft that they’ll do it, so you should work here.’”

“I hope that this starts a tradition in Pakistan, and we can make more films like this and encourage more kids who wanna be doctors to become artists,” says Paracha. “That’s our dream.”

Creating an animated film is an artform, but key to any film’s success is fundraising and eventually selling the finished product for global distribution. It was at a summit in Karachi where the team met Rashna Abdi, who introduced them to her college friend, top Spanish animation producer Manuel Cristóbal (Wrinkles, Buñuel in the Labyrinth of Turtles). Paracha remembers “We googled him and we were like, ‘This is Manuel Cristóbal!’… Obviously we knew of him, because [Wrinkles] was the first [international] film bought by Ghibli to be seen in Japan.”

“I thought it was just gonna be a polite talk, and here we are,” laughs Cristóbal from Annecy, where he joined the team for their work-in-progress pitch.

He now serves as executive producer on The Glassworker. Says Cristóbal, “I was mesmerized to see Usman’s work; he is so committed. … We had this standing ovation after the [Annecy] presentation. What I saw in Usman and the team and the film, that’s something the room saw.”

An experienced producer, Cristóbal warns that talent only gets you so far. “I think that’s one of the things that talent needs to understand. Apart from sheer talent, you have to put your blood into your films.” That’s something he believes the team at Mano Animation does everyday. In fact, the Monday morning after their trip to Annecy the team was back in the studio to continue their work on The Glassworker.

As Riaz says, “This film is a labor of love. It’s a love letter to the films I grew up watching and the films I love. I hope people find something that they love about our film when they see it.”

.png)