Terrence Malick Prefers Old-School VFX For ‘Voyage of Time,’ Opening Today in IMAX

For many vfx supervisors, visual effects is all about replicating reality. Which makes Voyage of Time, Terrence Malick’s IMAX documentary about the birth and death of the universe, quite possibly one of the pinnacle effects projects.

That’s because the film features a combination of microbiological, planet-based and space-based images, some real and some made possible only via practical and digital effects.

“It’s kind of like the ultimate project,” said visual effects supervisor Dan Glass, a veteran of such films as Batman Begins, the Matrix sequels, and Malick’s The Tree of Life. “The visual effects material itself had to uphold to an incredibly convincing and real level.”

Voyage of Time runs the gamut from the origins of life to its anticipated death. Much of the footage in the documentary is live action, shot in many locations. Some is telescopic. Other imagery comes from scientific simulations or microscopic recordings. For pieces of film that could not be acquired in these ways, the director turned to Glass and a diverse team of visual effects contributors over several years.

Importantly, Malick didn’t want the visual effects additions to be heavily CG, even though they certainly could have been achieved that way. “He wanted to find analog solutions as much as possible,” said Glass. “Even if it meant the shots ended up being simplified as a result, it was still very important to have that kind of fidelity.”

To produce such shots, Glass participated in five or six sessions with what became known as the ‘Skunkworks’ lab. This was made up of scientists and artists who were invited to explore creative ideas and contribute to condensed shoots of practical effects elements.

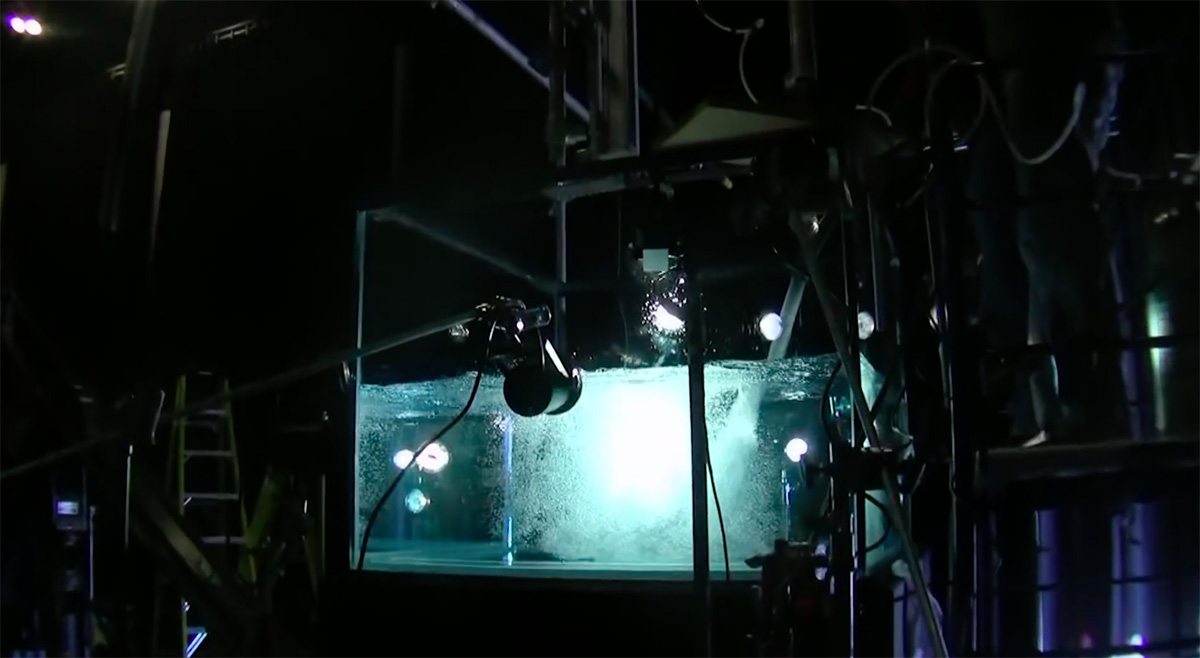

There would ultimately be several ways that visual effects shots would be produced. Techniques included smoke machines, models for comets/asteroids, fluid tanks for cosmic and microbiological imagery, filming super-heated clay, shooting ferrofluids in a magnetic field to create organic shapes and suggest black holes, and even sprinkling salt crystals on a spinning disk to represent asteroid belts. The imagery might eventually have been digitally manipulated—by VFX studios including Deluxe’s Method Studios, One of Us, and Locktix—but it often started as a practical element.

“There was a huge variety of things we played with on camera to come up with what we were specifically after,” said Glass. “But very often we were trying to create some interesting visuals that would become apparent after the fact how they might fit or help us in the timeline. We weren’t always trying to create something intentional. It was like a documentary with creative exploration and letting some of the processes guide us.”

Sometimes real life scientific imagery was not directly used, but informed the filmmakers on what would be a good fit for the documentary. For example, for a microbial sequence showing how one cell consumes another, it was deemed that typical microscopic footage would be too flat and planar to appear on screen. So it was combined with the more three-dimensional feel of electron microscopy.

“The scene is a key and very important aspect of evolutionary development towards more complex organisms,” said Glass. “We found an example of that as microscopic footage and roto-mated it so that we had a digital version. To understand how these things look in three dimensions we then went to electron microscopy which can show you the incredibly rich and dimensional look of small-scale life. But it’s inanimate and dead, the nature of its process means you can’t shoot it in motion—yet. So we’d take that reference and use it to effectively build out the motion.”

More traditional digital visual effects also came into play, including creature work. One sequence called for a reptile that existed before the dinosaurs to be shown on screen. Background plates were filmed in the Atacama desert of Chile and then a CG model was built, textured, and animated.

Even with the digital creatures, Malick typically filmed scenes to be backlit, meaning much of the detail was kept in silhouette. And, said Glass, “we weren’t always trying to shoot where the creature would be in the shot. We just let the shot play for what it was and would then find a way to embed the creature so it felt not completely like it was staged for the creature. It was about trying to give it a feeling of a documentary where it sat there and we happened to get a fortunate moment with it.”

For Glass, Voyage of Time proved to be an opportunity to apply many of his visual effects skills—past and present—to craft a range of phenomena. Some of the results weren’t necessarily realistic depictions of the transformation of the universe, but they were designed to have the effect of communicating so, and to ‘feel’ realistic.

“It required all the knowledge I’ve gained over time to know what techniques would be appropriate,” said Glass, “and knowing how to interpret what a filmmaker like Terry was trying to achieve. We couldn’t talk in a technical language so we had this different level of understanding and derived it from there.”

.png)