See The Sizzle Reel For ‘Galaxy Gas,’ A 2D Feature By Disney All-Stars That Never Made It To Screen (Exclusive)

When Klaus was released by Netflix last year, it was heralded as a revival of hand-drawn animation — as evidence that a 2d feature could justify a decent budget and find a global audience today. Had history taken a slightly different course, that accolade might have been given to another film.

Galaxy Gas was supposed to be many things. A zany, heartwarming sci-fi story featuring drunk aliens and spaceships aplenty. A reunion of an all-star creative team of Disney veterans, led by Beauty and the Beast co-director Kirk Wise. And a demonstration that there was a general appetite for hand-drawn animation (with a contemporary twist).

The project came within inches of starting full pre-production before falling apart, but a trailer was created in 2014 for potential production partners and investors. This sizzle reel was never intended to be seen made public, but six years on, its producer Craig Peck is ready to share it, exclusively with Cartoon Brew. He tells us that “if this can bring a small amount of joy to people during a difficult time, that would be fulfilling for those of us who worked on it”:

Peck continues to lead a busy career and he is involved as a producer with two upcoming films: Alcon Entertainment’s long-gestating fantasy feature Darkmouth and Disney legend Andreas Deja’s short film Mushka.

The story of Galaxy Gas begins back in 2012 when Peck was a grad school student with a burning ambition to make hand-drawn features. His idol was Don Hahn, the producer of Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King. Naturally, when Peck set about finding a project of his own, it was to former Disney talent that he turned.

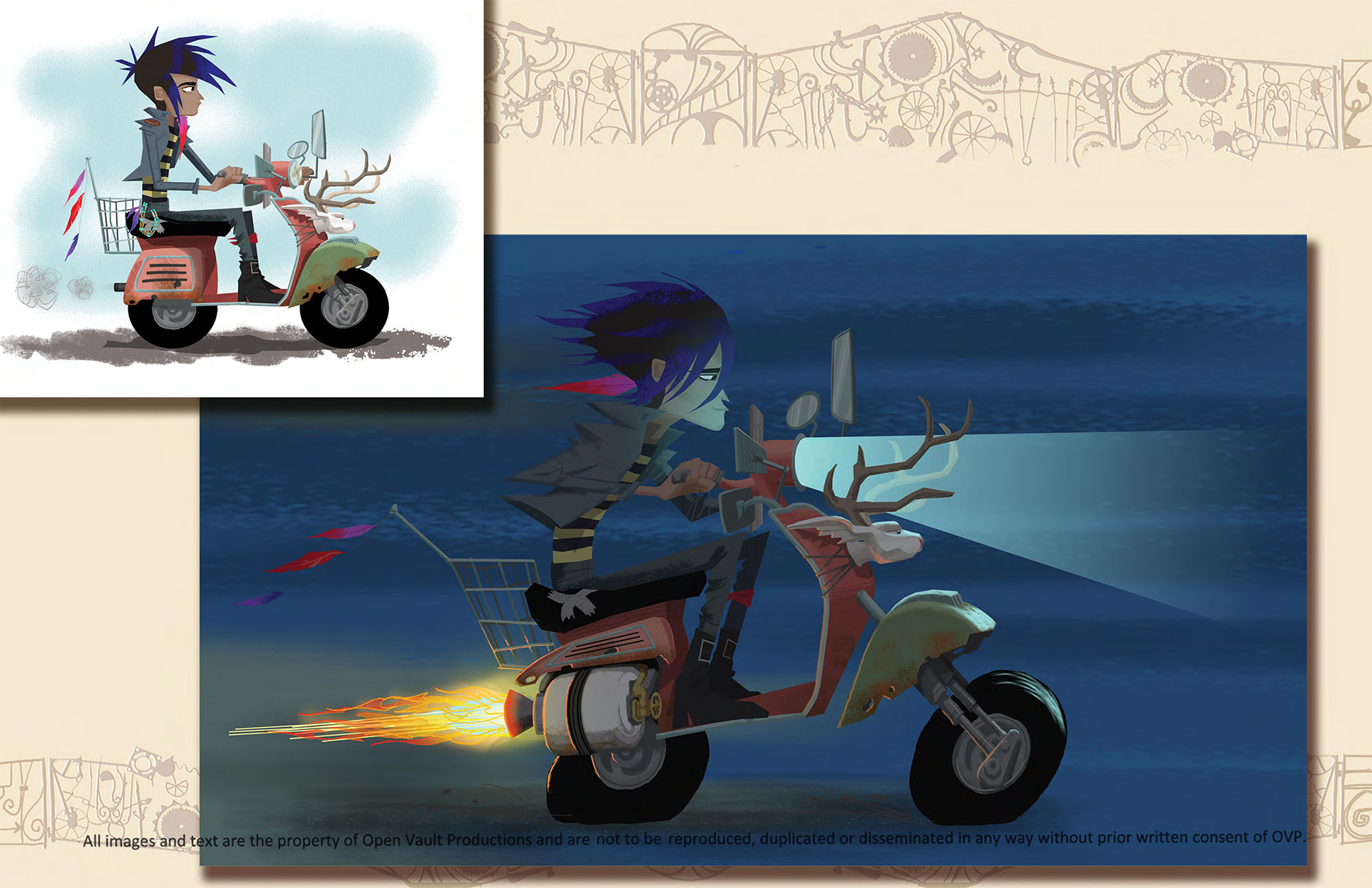

He contacted Tab Murphy, the screenwriter behind Tarzan, Atlantis: The Lost Empire, and The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Peck asked him if he had any ideas for a 2d feature. Murphy pitched an idea about a teenager who discovers that his father, who runs a lonely gas station in the New Mexico desert, is actually using it to refuel the spaceships of alien peace-keepers. Peck loved it.

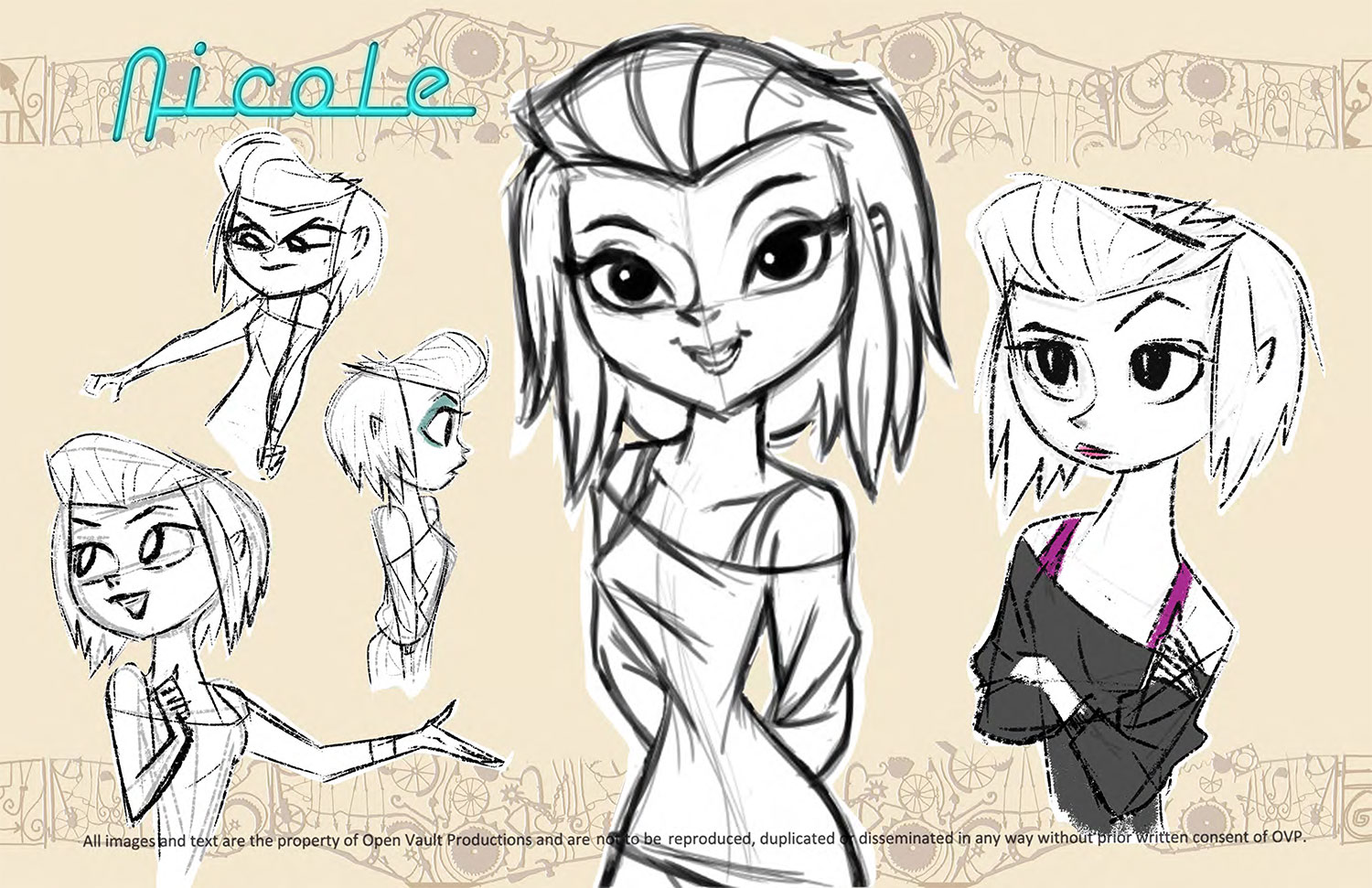

The pair then presented the project to Wise, who had directed both Hunchback and Atlantis. Wise loved it too, and was keen to do another animated feature — he hadn’t directed one since Atlantis in 2001. He signed up, and the project snowballed as a host of former Disney colleagues came onboard: art director Brian McEntee, layout supervisor Ed Ghertner, story artist Joe Haidar, character designers Joe Moshier and Shane Prigmore, and animators Ruben Aquino, Bruce Smith, and Nik Ranieri, among others.

If this line-up proves anything, it’s that a project can’t succeed on talent alone. As the crew geared up to start work, they were stopped in their tracks by circumstance. Production never began — at least, it hasn’t yet. Below, Peck talks through the ideas behind Galaxy Gas, and explains why he’s bringing it to light at last:

Peck: After my time in the talent development program at Disney Animation Studios during the production of Winnie the Pooh (2011), I saw that hand-drawn was once again going to take a backseat at the studio and that some of their incredible talent, at the height of their abilities, were going to become available. I felt there was still a meaningful demand for hand-drawn American features.

Also, taking a longer-term view, in order for the next generations to carry on many of the lessons gleaned from the past century of hand-drawn animators, I believed we needed the opportunity to learn directly from the current masters, working alongside them in the thick of production. The plan was to fill half of the crew with veteran artists and the other half with less experienced but passionate artists who could bring their own sensibilities to the show.

Prior to initiating work on the test and script, I took nine months off school to travel the country, raising money to pay for development from individual high-net-worth investors. Once that was complete, we began work on the screenplay, animation tests, and early visual development — all elements we wanted to have in place to secure actor attachments, financing, and distribution. Kirk and I developed the script with Tab while Brian [McEntee] and his team began exploratory artwork.

The script felt like it could organically mix hand-drawn elements while still utilizing cgi for spaceships and other high-tech elements. This aesthetic was intended to separate us from the crowd of mid-range budget independent films while targeting an untapped demographic of audience members. We were working to apply cg textures to hand-drawn characters in a way that would bring more depth to the characters.

We had also converted the animation test to stereo 3d with an incredible studio partner. Our creative leadership had never seen this type of fully fleshed-out hand-drawn integrated into 3d like this, and it excited everyone as to the possibilities. The test was animated on paper, but the feature was going to be animated entirely on Cintiq tablets.

The team set up a weekly “sweatbox” at the Burbank Public Library, up the street from Disney. It was a blast being crammed in a tiny reading room each week with some of the greatest artists in animation, watching Kirk give notes on the team’s work displayed on my laptop. This was very much a guerrilla project made with extraordinarily accomplished filmmakers, many of whom began their careers in a similar setup.

All the artists did their work from home and I worked as the sole production person, handling everything from pencil-testing scenes to attaching actors and distribution. By the delivery of the final materials, over 40 people had contributed in some way to putting this together, from storyboards to final sound mix.

Truthfully, the hand-drawn aspect of this film and the passion that the creators had in seeing it through garnered us a lot of goodwill from financiers, actors, distributors, and other partners that I don’t think we would have seen had this been cgi. Each meeting saw us talk about why we need to propel hand-drawn features forward, why this story was so personal to each of us, and why we were willing to go above and beyond to see it through.

We managed to attach A-list actors, a superstar composer, a movie star as executive producer, a well-known and well-capitalized co-finance company, as well as a top finance/theatrical distribution company — all because people believed in the passion and they themselves had real love of the art form.

The major theatrical distributors certainly showed little interest in releasing a hand-drawn film, but the mid-level distributors who could handle a film of this budget and didn’t need to spend enormous amounts of money in prints and advertising to break even were the ones that we felt were our best shot. Unfortunately, the number of those distributors was extremely low when we brought the project to market, and is even lower today. But luckily it has been replaced with incredible streaming options like Netflix, which released the awe-inspiring Klaus.

We were extraordinarily close to beginning full pre-production. The executives at the finance/distribution company took the full creative leadership team out to celebrate the launch of the film. I remember seeing the Cintiqs set up at our partner studio, each with a sign welcoming the artist assigned to that office or cubicle. I spent months re-budgeting and re-scheduling the film for the distributor, working with the bond company, negotiating deals.

And then it was revealed the company didn’t have the funds they said they did, and we hit the “pause” button. (This was a major company with many films under their belt and their numerous employees didn’t realize the company was soon coming to a close either.) The ensuing months saw a few other things that were out of our control and our momentum was lost. At that same moment, the few remaining mid-level distributors began going out of business.

We all love the project deeply and if the opportunity to revisit it came up, we’d love to do it.

(Peck’s comments were taken from longer answers sent by email.)