‘Sausage Party’ Directors Conrad Vernon & Greg Tiernan On Making 2016’s Most Outlandish Animated Film

The adult animated feature is a rare specimen in the United States, especially an R-rated project that has the full backing of a major Hollywood film studio. Sony aims to change that today by releasing Sausage Party in over 3,000 theaters, easily making it the largest launch ever for an adult animation project.

The film has all the makings of a hit (at least we think so) : it was conceived and written by proven names from the world of live-action filmmaking, it received terrific early buzz, it’s benefited from an unconventionally good marketing campaign, and most of all, it’s a solid film that both delivers on, and transcends, its ridiculous premise.

The latter credit belongs to the film’s directing duo: industry veterans Conrad Vernon and Greg Tiernan. Vernon, who co-directed three films at Dreamworks, including Shrek 2 and Madagascar 3, had worked with Rogen on the production of Monsters vs. Aliens.

Afterward, Rogen pitched him Sausage Party, an idea he’d conceived with frequent collaborators Evan Goldberg and Jonah Hill. Rogen described the film to Vernon as a film about “a bunch of hot dogs that escape their packaging to go fuck buns.”

Vernon, who discovered Heavy Metal and Ralph Bakshi films as a teenager, had been wanting to make an R-rated animated film of his own for most of his career, and jumped at the opportunity to helm Sausage Party. He invited Greg Tiernan, whom he’d worked with on Bakshi’s Cool World in the early-1990s, to become a co-director on the film. Tiernan would produce the film at his Vancouver, Canada-based Nitrogen Studios, which he’d opened in 2003 with his wife, Nicole Stinn. Prior to Sausage Party, their company had focused mostly on children’s animation with their biggest credit having been the CG Thomas & Friends series.

In a phone interview with Cartoon Brew, Vernon and Tiernan spoke about the challenges of selling an R-rated animated feature in Hollywood, producing a film on a fraction of the budget of Hollywood CG animation features, and knowing when you’ve gone too far in an R-rated cartoon. These are excerpts from our conversation. [Spoilers ahead]

Congratulation on Sausage Party. I think a lot of people in the feature animation industry will be rooting for it because we need more films like this and this is a great example of what animation can be and where it can go…

Conrad Vernon: Greg and I always like to say, for a long time animation has been seen as a family/kids’ medium—even genre—because that’s pretty much the only films that are made in animation today. And the reason it was really important for us to make this movie is because we wanted to tear down that wall for telling different types of stories, and bringing different genres into the art form of animation. When we were pitching this, we had Seth [Rogen] and Jonah [Hill] promising to star in it, I was going to direct it, we had Greg’s studio and he was going to co-direct with me, we had a script written by Seth, Evan [Goldberg], Kyle [Hunter], and Ariel [Shaffir]. That was a pretty damn good package along with all the artwork, and people still didn’t understand what we were going for because it had never been done, which is kind of amazing to me. Most live-action studios were saying we don’t understand animation so we don’t want to get involved, and most of the animation companies were like, we have a brand name and we’re not ruining it with this movie. So we were kind of stuck between a rock and a hard place, but thanks to [Megan Ellison’s] Annapurna and Columbia/Sony, I hope that we have opened a door and proven that there is an audience and a viable market for this type of animation—that people of all ages love animation, so filmmakers should be able to make all kinds of animation for different audiences.

How many other studios did you pitch it to before Annapurna and Sony got involved?

Conrad Vernon: Oh, dozens. We went to big ones, small ones; we even started talking about maybe private investors. We wanted to get this done really bad, and I can promise you if we hadn’t sold it to Annapurna and Columbia, Seth, Evan, Greg, and I would still be out there pitching this movie, trying to get it made.

This film should make a big impact and really expand the market for different kinds of animation because you definitely did it right.

Greg Tiernan: That’s what we did set out to do, and we just made that one small step. Everyone else can get in there through that little crack in the door that hopefully we’ve opened up.

Cartoon Brew: Greg, Nitrogen Studios does a lot of service work on children’s properties. Did you have any concern about doing an R-rated film and how it might affect the studio’s reputation as a producer of children’s entertainment? Or was it a choice to change the studio’s trajectory?

Greg Tiernan: To be honest with you, there was no sort of plan to change the trajectory of the studio or what we focus on. Basically, we set up the company to do as high-quality, cutting-edge animation as we possibly could. We’ve been fortunate in all these years that we’ve had our pick of projects to work on and we only want to work on quality animation. When we took on Thomas & Friends, we elevated that show, and there’s not been too many preschool shows with the production quality of Thomas. So it doesn’t matter whether it’s Thomas & Friends or whether it’s Sausage Party, we’re in the business of animation. That’s all we know how to do.

The production cost for the film has been reported in the entertainment press as being around $20 million. First of all, is that accurate, because it sounds extremely low for a film with this level of production value, and if it is accurate, how were you able to achieve such quality at that price point?

Greg Tiernan: Neither Conrad or I can confirm or deny that actual figure, but all I will say is that when Conrad pitched the movie to us, and we made our pact and vow to Conrad, and to Seth and Evan, and eventually to Megan Ellison at Annapurna and to Sony Columbia, we knew damn well that we could deliver a movie that looks like a $150 million movie for a fraction of the cost. That’s about as close as I can get to confirming or denying that figure. In general, that’s the whole reason we started the studio 13 years ago. After working in the L.A. industry for many years, I could see so much money just needlessly thrown down the toilet in making a lot of these movies. It doesn’t have to cost that much money when you’re well organized, and you have your mind set on the goal of what you want to do, and you get the job done with a small, determined crew. But yeah, let’s just say it was a lower budget movie.

Conrad, you directed for a long time at Dreamworks, where the films have higher budgets and you have more resources at your disposal. What adjustments did you have to make to direct a film that’s a fraction of the cost of a typical Dreamworks film?

Conrad Vernon: Greg and I approached it as we would approach anything else. I’d done three films at Dreamworks so I kind of knew what kind of a production line I wanted to [use], and Greg had a very similar production line, so we were on the same page there. And instead of trying to simplify this movie so that we can fit within this budget, we just said let’s make a beautiful, great-looking, well-animated, cinematic film, and see where we have to pull back. I’d rather go too far and have to pull back a little bit than not go far enough and say, “Wow, we came in under budget. It’s too bad we couldn’t make the film look better.” So Greg and I creatively approached it like we would approach any other movie.

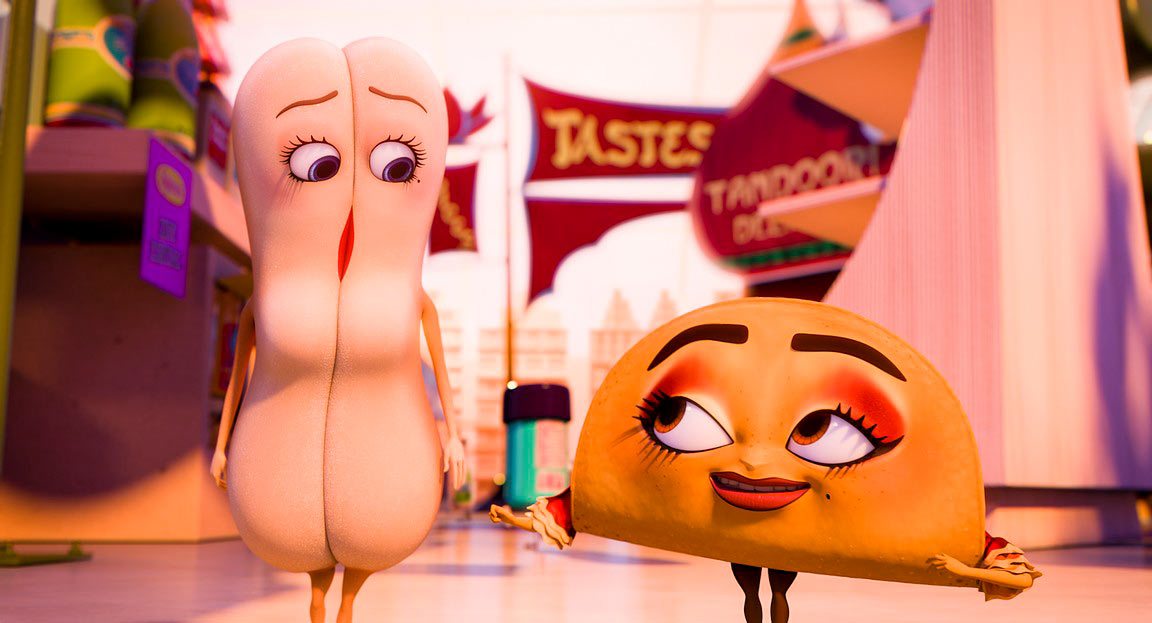

There’s something that I’ve been wanting to do since the day I started at Dreamworks that we got to do on this film, which was take our characters and make them very appealing, but very simple design-wise. Craig Kellman did a brilliant job helping us out on that. Then, when we rigged them, we had the animators actually go in and take shots from old Bob Clampett cartoons, and Popeyes and Chuck Jones stuff, and literally rotoscope our character over it to make sure that they could do all the crazy stuff that those old cartoons did, so that we could get a really good, loose 2D-animated feel to these characters. We used multi-arms, wipes, dry brush effects—we did all that stuff, and it helped give a unique style, but it also wasn’t horribly expensive to do.

At Dreamworks, you answered creatively to Jeffrey Katzenberg. Who did you answer to creatively on this film?

Conrad Vernon: Well, Greg and I first, and then Seth and Evan. But it was nice because they worked as partners with us. They were in charge of the script, and we were all in charge of recording the actors, and [Greg and I] were in charge of the animation. We always sat down with them every week, like on a Friday or something, and ran them through all the designs, all the character stuff, all the animation, the effects, everything, so that they had an input, but 95% of the time, they’d look at it and just go, “Beautiful. We love it.” As far as the studio was concerned, they were really, really supportive and pretty hands-off. We only had, I think, two or three screenings for them, and they came in with some really great notes. We went through them, saw the ones that were really helpful and would get us to the next level, and then we moved on. Sony and Annapurna were nothing but supportive, and said, “You guys are the creators; you’re in charge of this. Go and make your movie and we’ll be here to help whatever way we can.”

Greg Tiernan: Just to add to that, for me and everyone up here at Nitrogen, we felt that we have never worked on a project that has been so collaborative. We have learned so much from Seth and Evan. It was awesome that they just said, “We don’t know anything about animation. We love it, we appreciate it, but we don’t know how to make it.” They basically just let us do our job, which was awesome, and we were exactly the same with those guys with the live-action sensibility. We tried to make sure that we didn’t pace and cut this movie [in a way] that would be typical of every other animated movie. It’s got more of a live-action sensibility to it because everyone involved in the movie from Sony Columbia, Annapurna, and Seth and Evan, are all live-action folks. We’re the only animation people here. It was really super collaborative, and for sure the best experience of my career, absolutely.

What you’re describing is very different from a lot of times when live-action people become involved in animation. When we spoke to Genndy Tartakovsky about making Hotel Transylvania 2, he was vocal about how Adam Sandler wanted to take control of the film, which can be problematic when someone doesn’t fully understand the process. Did you run into such difficulties or was it a smooth process?

Conrad Vernon: I can say, looking back, that it was a smooth process. Yes, they didn’t understand the animation process. That’s why they brought me in, and they pretty much just said, “Take care of that. Just keep us in the loop and keep us involved with what you’re doing and explain it.” Now, there were a lot of changes that we needed to make—there were some changes that we made after something was animated, there were a couple of lines changed after something was lit.

Basically it came down to a very simple act of sitting down and talking about whether or not the film was going to be better for it. Greg and Nicole [Stinn] at Nitrogen were really supportive of saying we’re going to try and push this through the pipeline; Annapurna was really supportive of saying they’ll kick in a few extra bucks to make it happen. And that’s all it really was—it was just making sure that that collaboration existed and that the communication was really clear. We’d all sit down [and talk]: This is going to cost this much money, it’s going to take this much time. Can we do it and is it worth it? Sometimes it was and sometimes it wasn’t. But there was never any acrimony that went along with it. There was some stress to be sure, but there were no creative disputes over it.

One of the things I really appreciate about the film is the duality of the characters. When they’re amongst themselves they have eyes and mouths, and when the humans are looking at them, they’re just inanimate objects. The concept was communicated very well cinematically, and I wanted to know more about who came up with the idea: was that in the script or was it something you came up with during the process of developing the film?

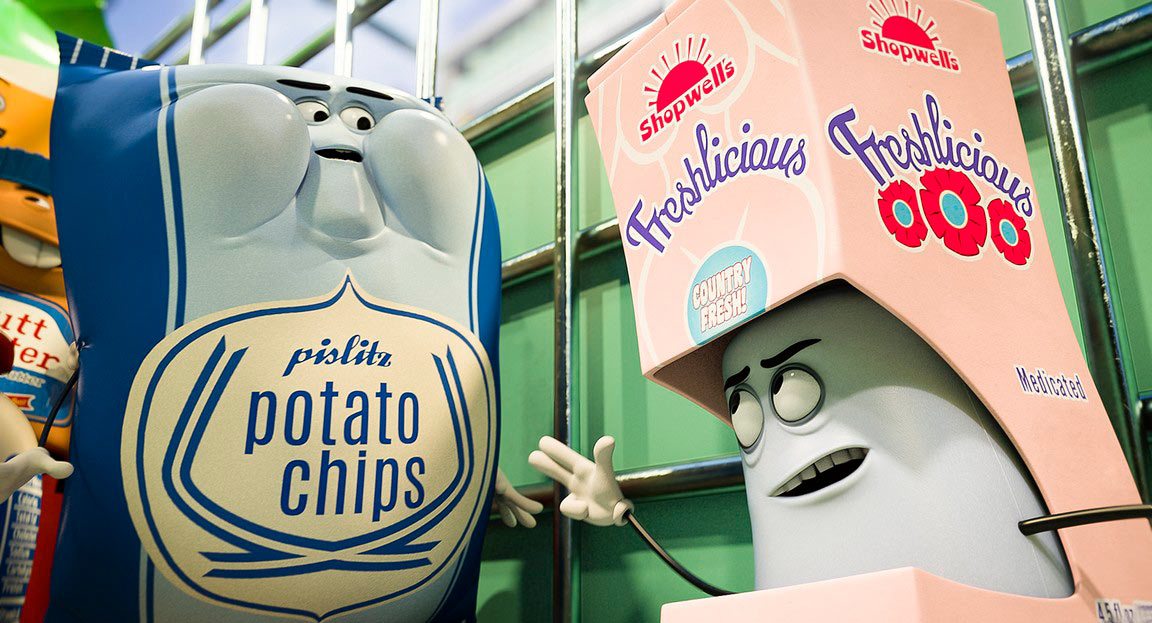

Greg Tiernan: That’s an interesting question because that was one of the very first hurdles that we gave ourselves of how are we going to make sure that this is clear. The actual execution of how we were going to put all of this together was totally handed over to Conrad and I, which we were very grateful for. There were quite a few little problems here and there on the theory and logic of the world. Every now and then, it’s like, “Wait a minute, how come this bag of chips is alive and those ones aren’t,” but hopefully we weaved enough through there to make it a fairly solid foundation.

Conrad Vernon: We were really cognizant of how we were going to show that change visually as well. If you really look at the movie, you can see that when we’re in the food’s point of view, it’s a lot more colorful and we have a lot more saturation, and the camera angles are more dynamic, and the music is scored to be big and full. When we go back to the human point of view, we desaturated everything, and kept a locked-off camera most of the time, and put canned, cheesy grocery store music, just to make the food’s world much more interesting and much huger, because this is the way they’re seeing the grocery store.

Maybe my minds in the gutter, but I actually was expecting the film to be much more raunchy and perverse…

Conrad Vernon: You’re the first person who’s ever said that to us. [laughter]

But what I’m getting at is that the film has a lot of heart and it’s very cute in some ways. Was that a conscious decision or did you have to constantly pull back to make the film more accessible to audiences?

Greg Tiernan: There was definitely a conscious decision right from the get-go. Conrad, myself, Seth and Evan, and the two writers Kyle and Ariel, we all sat down together, and Conrad was the first one to impress on Seth and Evan that just because the subject matter of the animation involves R-rated stuff, sex and drugs, and all sorts of ridiculous stuff going on, the movie has to have a heart and a soul. You have to empathize with these characters, and there has to be a really meaningful subtext to the whole thing. So we had to make sure that it was way more than just a big, literal sausage fuck-fest.

Conrad Vernon: We definitely wanted to make sure that there was a real emotional story with heart. As far as the characters were concerned, we needed to make them appealing, and as you say, cute and lovable, because of the stuff that’s going on. If we actually went too into that uncanny valley of realism, a lot of this stuff would just become disturbing and weird and off-putting, and you wouldn’t be laughing and wanting to see more. You’d be going, “Eugh!”

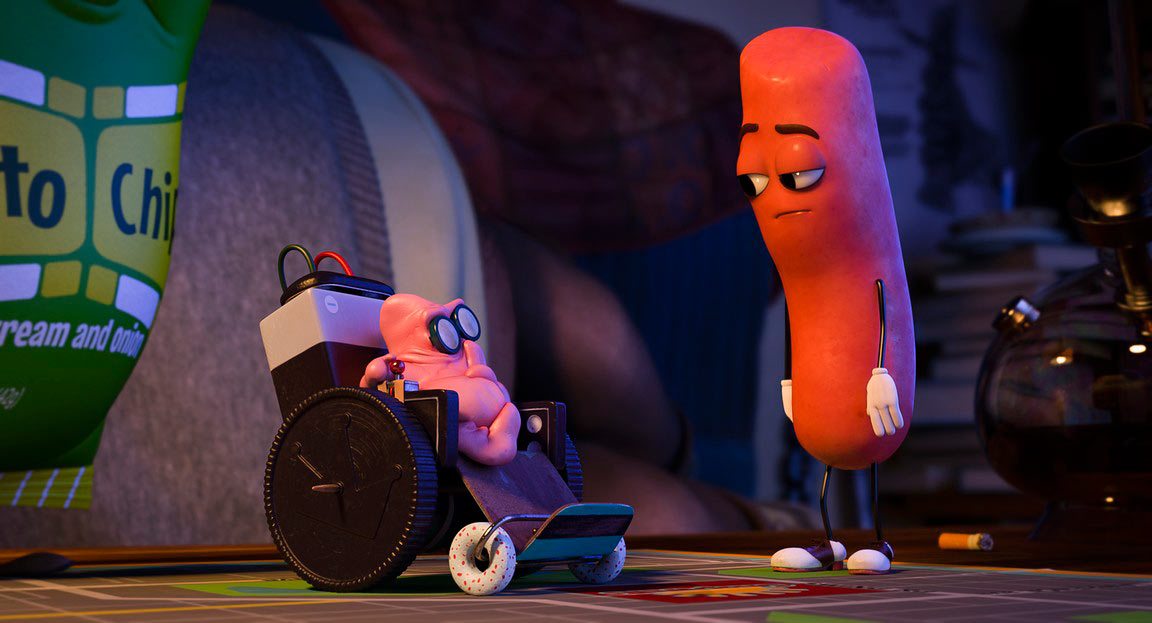

And believe me, in the making of this movie, we’ve crossed that line a few times and we know how that feels. So we just said to ourselves that we need to make this as fun as possible. When the druggie’s head gets sliced off and falls through the air conditioning vent, there were a couple of designs where we just took it into a really grotesque, realistic realm, and it was like, “Ewww!” It’s totally off-putting. But when we pulled it back and made it funny and goofy, then the reaction in the audience is [different]. When we come back from that flashback and Barry starts to soliloquy to Frank, and there’s this dead human head behind him, people are giggling through the entire speech that Barry gives because it’s so ridiculous. If [the severed head] had had blood coming out of his nose, or his eyes were all rolled back or glassy like a real human being, people wouldn’t have wanted to look at it.

Can you tell me other jokes or scenes where you think you took it too far and had to dial it back a notch?

Conrad Vernon: Well, the most famous one was when Douche had a group of rats that he met in the backroom, and they became his gang, and he would ride them around, in particular one big rat named Dangles who was trapped in a rat trap that he set free, and they called him Dangles because his nose was broken from the rat trap. At one point, Douche captures Lavash and he tortures Lavash by putting his finger into Dangle’s butthole and then going over and sticking it into Lavash’s mouth, and going in and out, in and out. First of all, this went on for way too long, and second of all, when we screened it in New York, people went from grinning to utterly shocked. It took us probably ten minutes to get the audience back after that joke, so we just took it right out.