‘Robot Dreams’ Is Unconventional In Every Way, Including How It Was Storyboarded – Exclusive

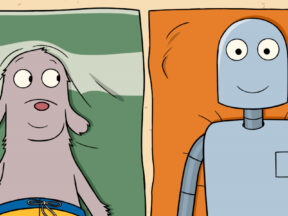

Pablo Berger’s Robot Dreams is exceptional among this year’s animated feature Oscar nominees. It was made for just $6 million; it was animated at a pop-up studio set up in the center of Madrid; and its director, a veteran of live-action filmmaking, had never worked in animation before.

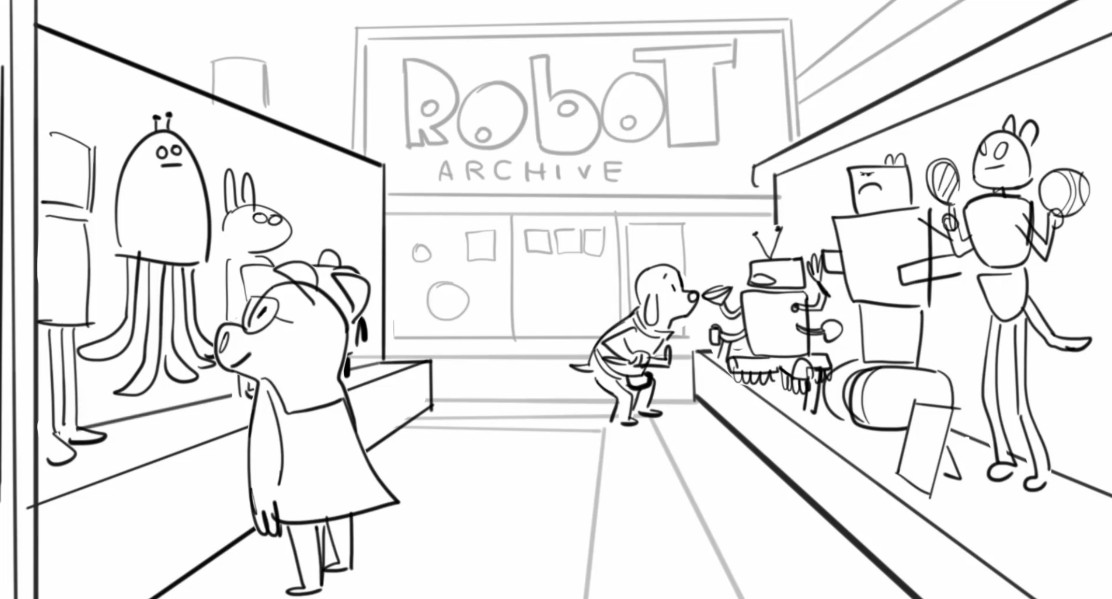

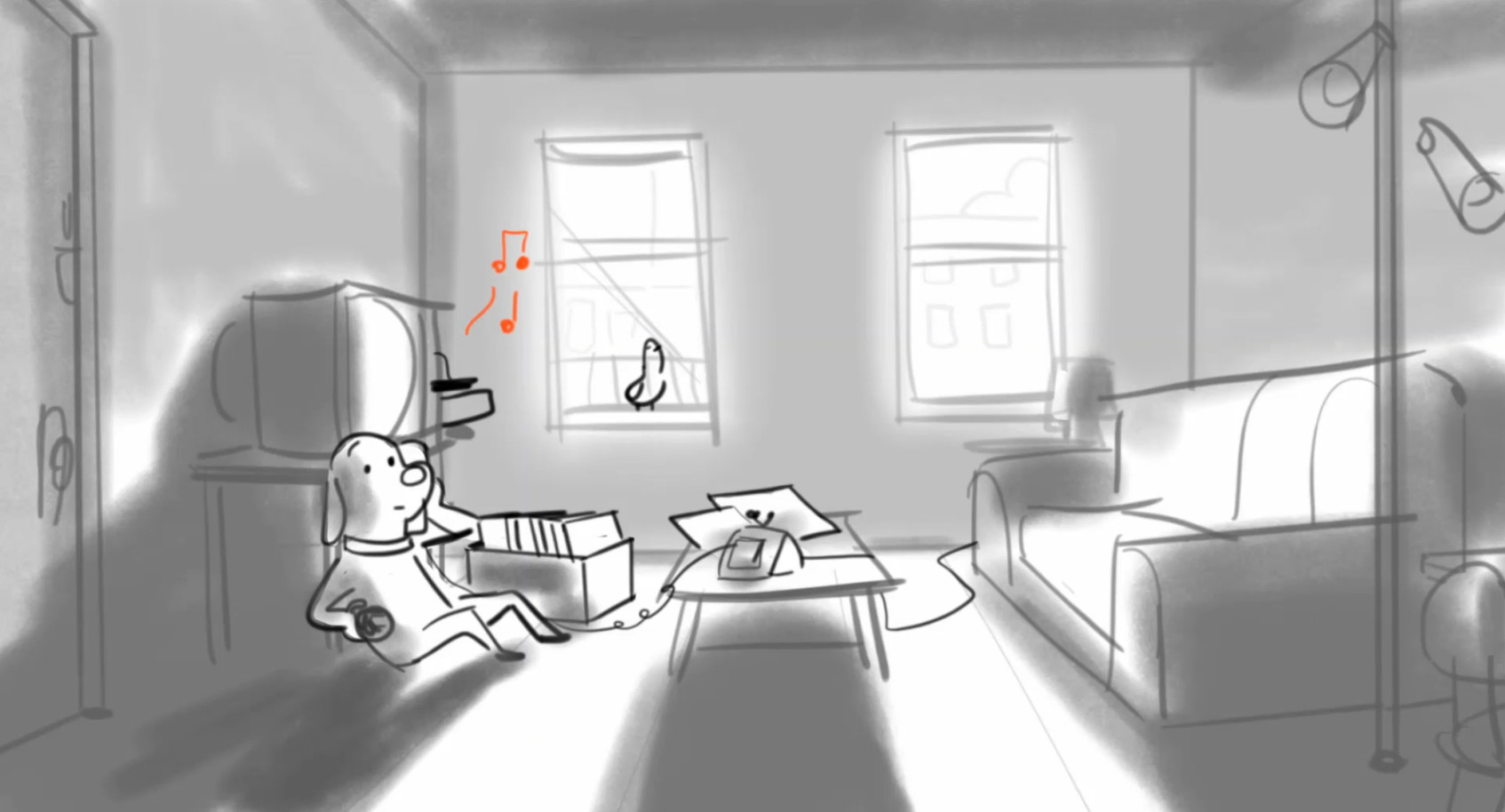

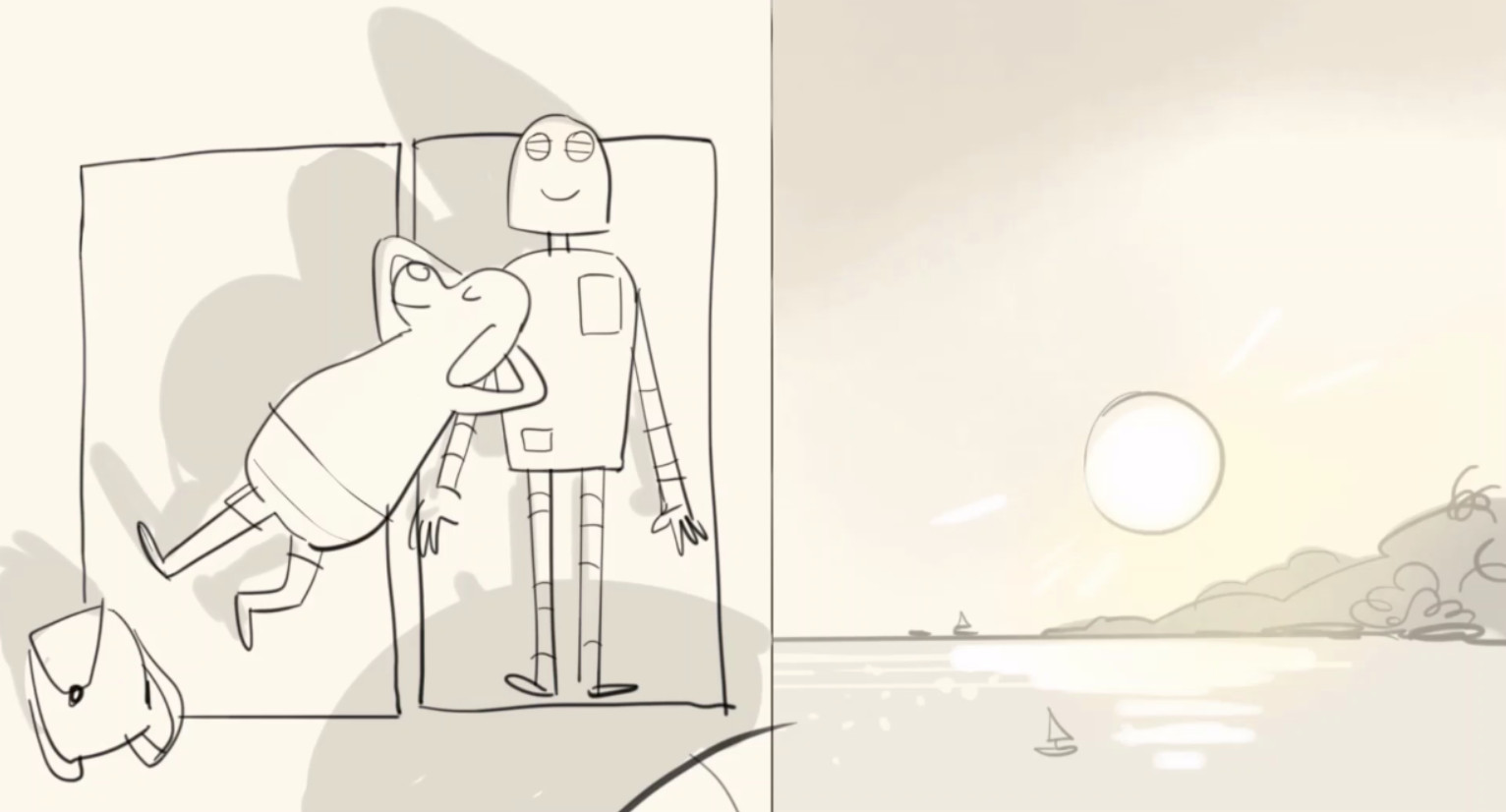

Another exceptional characteristic of the film was its unique storyboarding process. Berger, his art director Jose Luis Ágreda, and storyboard artist Maca Gil spent a year-and-a-half together in Berger’s Madrid office, working together every day to create the film’s storyboards and an extremely detailed animatic, an excerpt of which can be seen below:

Though Robot Dreams may be Berger’s first animated feature, he’s an accomplished live-action filmmaker perhaps best known for the contemporary classic Blancanieves (2013). Berger had drawn the storyboards himself for all of his previous films, which created an interesting dynamic when Ágreda and Gil joined him to work on Robot Dreams.

Intrigued by the unique setup, we caught up with Gil to discuss how she got involved with the film, how the film’s novel storyboarding process worked, and what it would take to replicate it.

Cartoon Brew: How did you end up as the storyboard artist for ‘Robot Dreams’? And how long did you work on the film?

Maca Gil: I was at Cartoon Saloon at the same time as Jose Luis Ágreda, Robot Dreams’ art director. We didn’t work on any projects together, but he said he asked for recommendations, and my name came up. The timing was perfect, too. I was going back to Madrid right as they were looking for a story artist to start on Robot Dreams, and it was very important for Pablo to have people go and work with him in person. I spent a year and a half next to him and Ágreda, the three of us working on the animatic in Pablo’s “camarote,” his office on Gran Vía.

How did the storyboard process on Robot Dreams compare to what you’ve experienced on other productions?

I had never experienced anything like it, but it worked out perfectly. Having the director and the art director right there with you cuts so many corners. Ágreda’s beautiful concepts of New York would be ready for clean-up, approved from the get-go, and put directly on the story.

The process was: They would brief me on a scene, I would work on the animatic using Ágreda’s concepts and thumbnails that he had prepared with Pablo, and then the three of us would sit and watch it together when it was ready. We each then gave our impressions and feedback, refining it until we thought it was perfect. Then, we’d move on to the next scene. The script changed quite a lot, so we pushed things visually and emotionally.

Do you think the process was one that could be replicated or implemented in existing animation pipelines?

I think for this to work, you need a director with full creative control over the story and a very clear vision. The good thing about just being the three of us, each with a clear role, was that the comments we’d give would be precise, direct, and addressed quickly, with no hierarchies or emails in between.

This process worked because Pablo knew the story he wanted to tell, and it was agreed from the beginning that we would be left alone to create it. He really listened to our comments and feedback, but no executives were there to demand story changes. We didn’t show anyone the animatic until we knew we had something we were proud of, something special.

Pablo told me that he storyboards all his live-action films, and in great detail. What was it like working with him on this production, and how involved was he in putting together the boards?

He was extremely involved. He had very clear directions and intentions. It has been one of the most creatively fulfilling experiences of my life, receiving instructions from Pablo and Ágreda. He wanted the animatic to express everything, to hit every storytelling point, to make you laugh or cry when it had to, so he appreciated extra details on the expressions or on the body language or even the background characters. I feel like you could see the finished film in the animatic. Doing a first editing pass of the entire thing was a very fun new challenge, too. Yuko [Harami, producer and music editor] and Fer [Fernando Franco, editor] came at a later stage and took the animatic to another level. The music made us tear up in every single screening of the ending.

Pablo also really cares about the art of filmmaking and loves cinema, which you can tell when working with him. Every day, Pablo, Ágreda, and I would talk about a film we had watched the day before. I watched so many films that year. Their goodbye gift to me was a huge book called 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.

How much did the Robot Dreams book influence your storyboards, and how much did you have to add or change things to adapt the story as a feature?

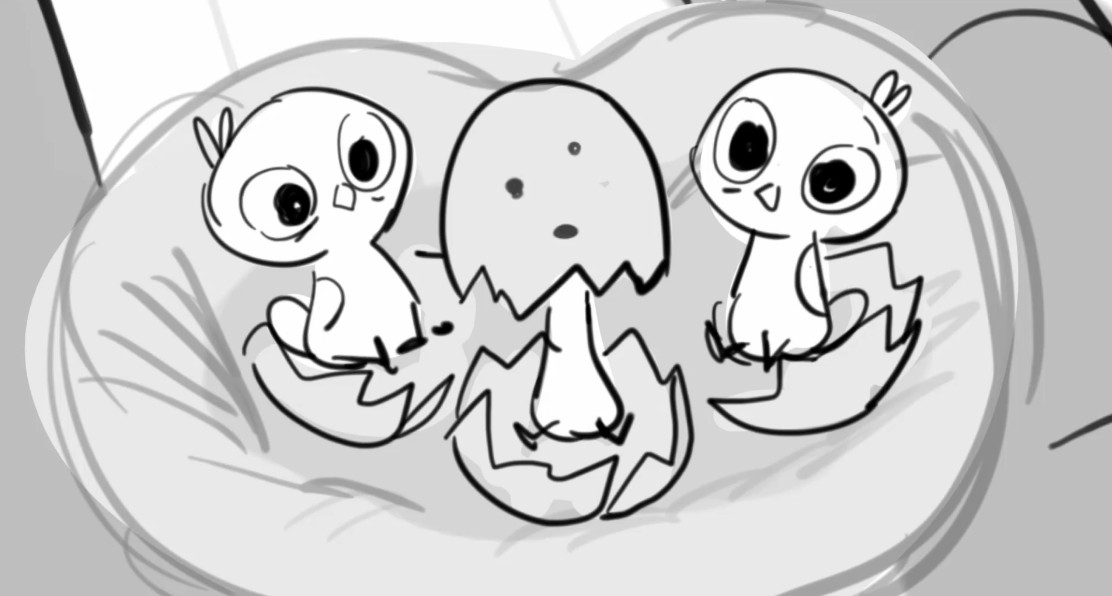

Sara Varon’s comic book has every key point that happens in the film. When you read the ending of the comic book, you feel the same bittersweet butterflies as Dog listens to the musical notes coming out of Robot’s boombox. We did have to make some adjustments; the first pass of the film had Snowman’s funeral because spring had come, and he had melted. This made Fer, the editor, raise a red flag. In Sara Varon’s graphic novel, there’s verisimilitude because the loose appearance of the world, where humans and animals live side-by-side, puts a sort of magical frame around it. When you saw Snowman in our film, with such a grounded New York and more solid rules, suddenly having something supernatural happen looked weird. In the final film, Dog wakes up from a dream. Snowman never existed. I remember we were against this at first: “The film is called Robot Dreams! The audience will feel cheated!” but I do think it makes so much more sense now.

The other main thing was New York as a character. For Pablo, it was very important for the city to feel completely real. The doorknobs, radios, and cars had to look how they looked back then. One scene had to change because Pablo realized the road goes the other way in real life. This was a challenge in and of itself, but Yuko did a wonderful job gathering all sorts of references so that Ágreda and I could draw, knowing exactly what we were drawing. I think it paid off because I’ve only heard praise for how well-represented New York is.

Robot Dreams will be released theatrically in the United States later this year by Neon.

.png)