The Oral History of ‘Space Jam’: Part 3 – Reflections on A Beloved Film

In honor of the 20th anniversary of Space Jam, Cartoon Brew has been taking an in-depth look this week at the technical challenges of making the movie. You can read the first two parts here and here.

Part 3 of Cartoon Brew’s oral history of Space Jam concludes with an analysis by the Cinesite vfx team on how they pulled off some never-before-done effects shots. Plus, members of the crew reflect on the legacy of the film.

Cinesite’s No-Holds-Barred approach

Jonathan Privett (cg gym design, Cinesite): 20 years ago, doing more than 1,000 shots on a show was considered insanity. As it turned out, it was insanity. I’m surprised a great swathe of early artists did not become alcoholics, not because of the pressure, but due to the fact we were in the Nelly Dean [a local bar] waiting for a render, or to load on shots by ‘tarring’ them ourselves off a tape. We had ‘Holly’ as our renderfarm – 16 CPUs and four gigabytes of shared memory, which cost about $1 million on top of which the deskside boxes had 256 megabytes of ram to splurge on whatever scene you needed to create and render.

Sue Rowe (digital compositor, Cinesite): It was back in the day when digital artists did everything. We would model, texture, animate, then match move and comp our own shots. I had come from a traditional animation background so Cinesite flew me out from the London office to help out on a tricky animation shot. They said I would be gone for two weeks; I came back two months later. It was a baptism of fire!

Jonathan Privett: I was responsible for the practice gym and because it had a shiny floor it needed reflections from the windows. Although there was a button to turn on raytracing, no one in their right mind would ever do that, excepting that they may want to go on a four-day bender while a few frames rendered, so we had to fake them in every angle we saw.

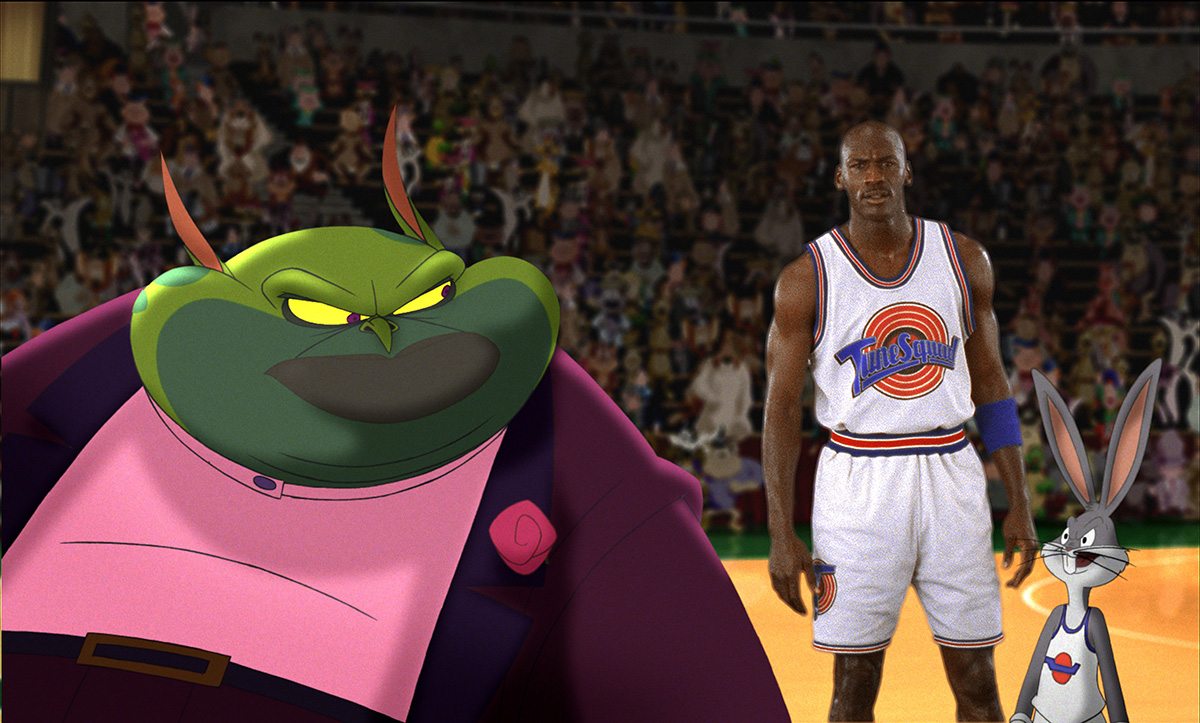

Carlos Arguello (digital effects supervisor, Cinesite): I think we had 94 different styles of the stadium for the final stadium to be chosen from. People think it’s one or two or three designs, but it was about 94 different styles because of the characters. Tasmanian Devil was brown so we couldn’t have a wooden brown upper level, and there were so many colorful characters, and Michael Jordan and everybody had to look good in all the scenes. So it was like designing and designing and designing and changing things over and over.

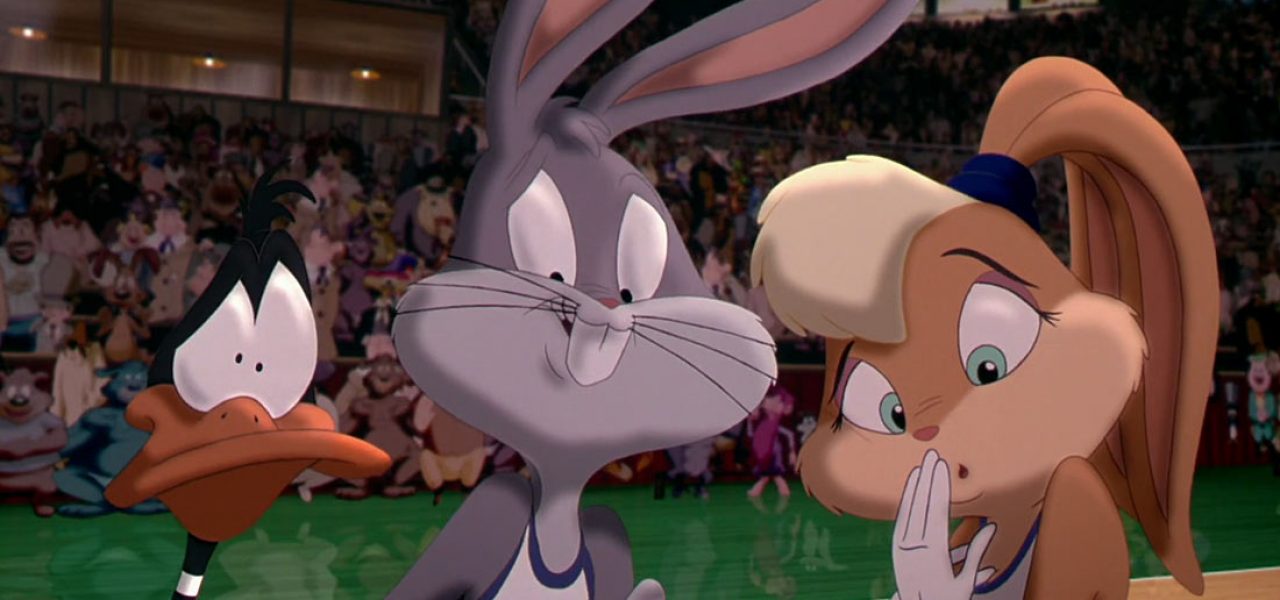

Ed Jones (visual effects supervisor): All the animation for the characters had tone mattes. And tone mattes can go anywhere from two or three a character to 30-plus for a character. Wherever we saw Bugs Bunny we really wanted to shape Bugs up really nice. Same thing with Lola – any of those that had those great two-shots or beauty shots, we always wanted to be able to control the sculpting, the sculpting being how we affect the lighting, the tonality, the gradation of that one color. So effectively we’re painting on film with light.

I used to describe it as almost like how Ansel Adams would dodge with neutral-density filters and how he would do still photography. Here we were just imagining light coming in and sculpting that. It’s the same thing as if you built the geometry for a 3D character, you’d have to light it in a turntable, or the same as trying to do it on a 2D surface and make it look 3D.

Neil Boyle (supervising animator): This was also at the beginning of being able to do video conference calls. Cinesite London had this setup where you could go and talk to the guys in Los Angeles. And so we would go there generally every Friday evening for us to talk to them about the week’s work and what we were going to be doing next week and so on. It was kind of funny because it was quite novel to have these video conference calls at the time. It seemed very Logan’s Run back then.

We would sit around the table, and we would all watch each other wandering in, trans-Atlanticly. But for them in Los Angeles it was ten o’clock in the morning and they’d all just come in from the gym or they’d been jogging and they were drinking their grapefruit juice, while for us in London it was the end of an exhausting 12 hour day or something. We were knackered. And we thought, ‘God, it’s not going to go down well if we’re sitting here having a beer.’ The Cinesite people in London were absolutely brilliant, we loved working with them, and we said, ‘Do you have a China tea service tucked away?’ And they said, ‘Sure, do you want us to make you some tea?’ I said, ‘No, no, just bring in the tea service.’ So they brought in a tray with this lovely teapot and all these teacups and saucers, and I just opened up a couple of cans of beer and emptied them into the teapot.

And then we went online, and all the guys come in from LA, saying, ‘Hi guys,’ looking eager for the day and we’re all sitting there knackered and about five minutes in, I said, ‘I’m just going to pour some tea here for the guys.’ And I would pour out this beer into the teacups, and they would go, ‘Oh god you British you can’t survive without your tea can you?’ And I’m going, ‘No, we can’t.’ And we’re sitting there with huge foaming teacups.

The Crazy Race To The End

Tony Cervone (animation director): Looking back, Space Jam was this project where they didn’t even know who was going to do it. And we were like, ‘We’ll do it!’ And then there was a release date with a ton of merchandise behind it and they said, ‘OK guys, we’ll see you in November, good luck…’ Which actually really helped. It’s very hard to make something when a studio is paying close attention. And no one was paying attention to us!

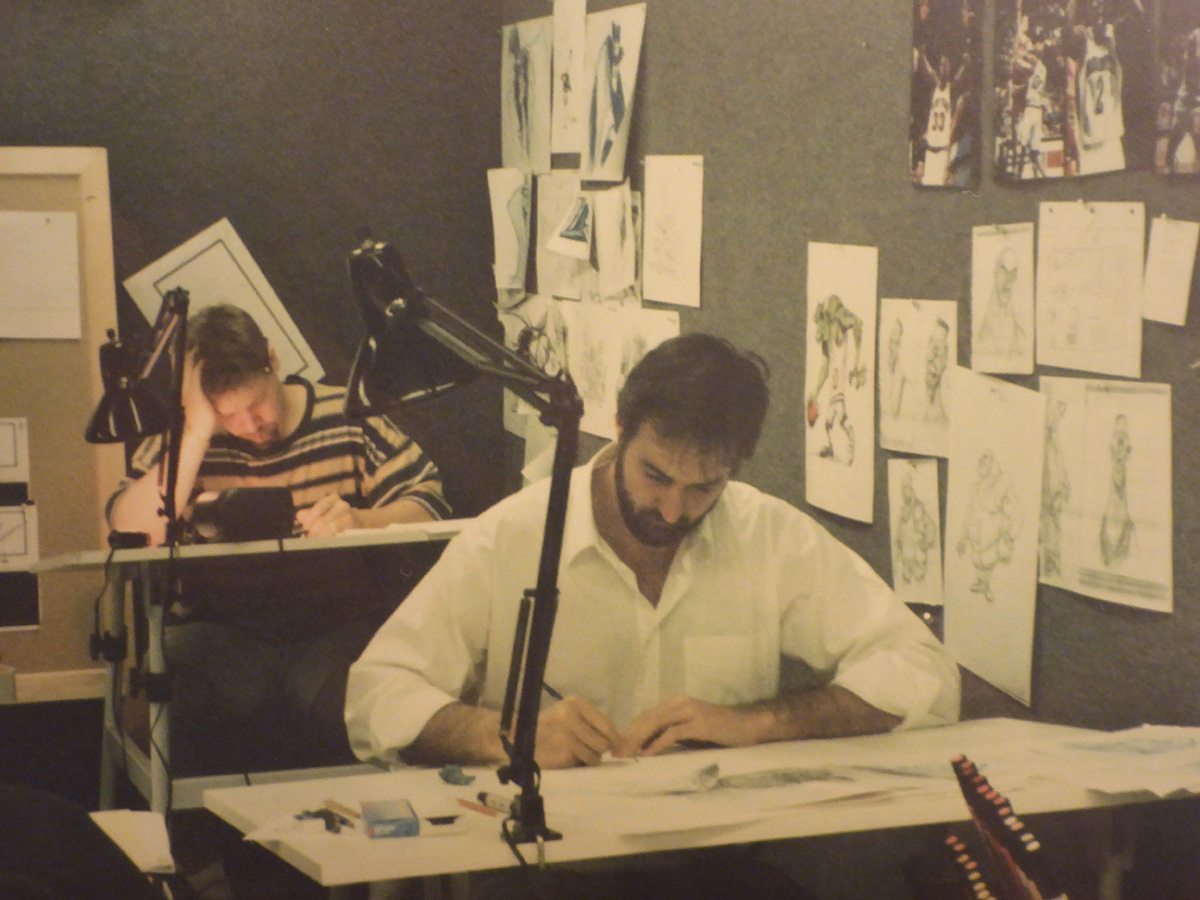

Bruce W. Smith (animation director): When we got into the ‘Hey man, we’ve got about three months left to finish this movie’ time, Tony and I were literally doing 24-hour stints where I’d work 12 hours at some point, and then Tony would come in and round out the other 12 hours.

Tony Cervone: In the last nine months, we would have one day off a month and work minimum 12-hour days.

Allison Abbate (animation co-producer): And no one minded.

Tony Cervone: Well, I wouldn’t go so far to say no one minded…but there was a real spirit and camaraderie and everyone chipped in. It’s not a perfect movie by any means, but we all poured so much into it. I think it’s one of the reasons we’re still talking about it years later. There is an incredible energy to that movie.

Neil Boyle: I fear we decimated several rainforests on this production. It was just a huge amount of paper and a huge amount of work. There were very long hours. But in fairness, with this production it wasn’t lack of money, it was lack of time. And everyone was paid very well. I think everyone would agree they were paid probably better than they were on a lot of productions and so people were very willing to put in the hours.

Fraser MacLean (technical supervisor: animation): The crew seemed to expand all the time. I must have been in Sherman Oaks for about eight months looking after the Animo stuff, and we were all staying in the Oakwood Apartments along Barham Boulevard. So I would drive in in the morning and I had two pagers on my belt—a personal pager and a tech department pager—and there were three of us on a 24-hour rolling shift so there was somebody there all day. But it sometimes felt like we were just there 24 hours. You would get paged and it would give you a number to call or tell you who it was, and you just had to run to wherever it was.

Matt Johnson (digital artist, Cinesite): There was a human-sized sketch of Bugs Bunny stuck up on our wall looking at his wristwatch with the delivery date printed on a bit of paper so everyone knew just how quickly they needed to get this stuff done. It was pretty intense!

Carlos Arguello: It was totally hectic; it’s a blur to me now. And right after Space Jam we worked on Free Willy, Barman & Robin, Sphere, and Armageddon. At the time we didn’t really realize that maybe some of those movies were building a whole industry that now the whole world takes for granted.

Jonathan Privett: A few of us got the call to go and help out in L.A. which was a fantastic few months, working 100 hours a week between sharing a rooftop jacuzzi at the now-defunct Summerfield Suites and chilis at Barney’s Beanery. It has to be said, we did occasionally get a bit overwhelmed with the number of hours and drove ‘round the block five or six times listening to Oasis’s “Wonderwall” before summoning up the strength to go into the office.

Tony Cervone: We had an early screening for the guys who ran the studio – Bob Daly and Terry Semel – and there’s that scene where Daffy is talking about being owned by Warner Bros. and he lifts his tail and the WB shield is on his rear end, and he kisses it. We just thought that was funny. We were walking out with the heads of the studio, and they go, ‘Do you remember when Daffy kissed his own ass? That was great!’ It was the opposite of studio interference.

It’s like the perfect movie to merchandise, so why would they get in our way? It was our move to put every character in and that was only because we loved them, and we felt it was our one shot to put every Looney Tunes character in it somewhere. That wasn’t a studio mandate – that was a bunch of people who loved those characters.

Sue Rowe: We worked very long hours on that show. I remember sleeping under my desk to make sure renders would go through the farm. We would do reviews with Ed Jones in L.A. at the end of our day and get feedback late in the evening, which they would expect to be done by the following day in L.A. We were so passionate about proving ourselves to Hollywood that we didn’t sleep or have much of a home life! Not sure if the industry has gotten any better?

Kevin Lingenfelser (digital composite artist and digital paint supervisor, Cinesite): As the film was drawing to the end of post production I was asked to delay my honeymoon, having just gotten married, until after the film was completed. They offered to pay for everything! I politely declined and had a fantastic time with my wife. This was the first time I had put family before a film. And 20 years later there are no regrets. Also, it helped that it was never held against me either.

Ed Jones: At one point Ivan Reitman looked at me and said, ‘Are you going to make it any better than that? Or is that the best and we should go with it?’ And I said, ‘I can’t do any more.’ It was as if we were running a marathon and I couldn’t get the next foot across the finish line, as if I had to die just then and say, ‘We’re done, let’s wrap this movie up.’

Sue Rowe: The wrap party was held at the Beverly Hills hotel in L.A. Our boss, Courtney Van de Slice, flew a few of us out there from the London office. We were picked up by a stretch limo with fizzy wine. I remember thinking, ‘Oh wow, this kid from a small town in Wales has made it!’

Memorable Shots

Tony Cervone: Some of those shots of Bugs and Duffy inside Michael’s house were so tricky. There are some scenes where they’re walking down a hallway and the camera is creeping down behind them – it’s either not locked down and moving, or it’s not moving fast enough. But we pulled a lot of that stuff off. No one knows how hard that stuff was to do.

Bruce W. Smith: One thing I remember that was really hard were those crowd shots. We had some really crazy swooping crane shots that we had to have these characters in, and they had to match everything else, and have the right dimension. They weren’t flat characters. These characters had to somehow have some form of dimension when the camera skewed itself at certain angles, and so the characters had to skew themselves also. So we had a technique that allowed us to skew these characters a bit, but we cheated a lot of it as much as we could. We lit it so that you wouldn’t notice a lot of things.

Matt Johnson: There’s a shot where we start with Michael Jordan in a press conference and it goes up through a cg roof and then you see the Chicago panoramic skyline, past a miniature, and you go up and then it carries onto this big sequence as you travel past the moon, and then you’re into the toon cg world. I did the initial transition from the room through Chicago, and actually used a camera that was used to do graphics and pack shots and things like that, so I just turned it on its side and I think I got a couple of people including myself just to stand against a white wall and kind of wave or make movements and things like that, and I just stuck us in the window. So if you look very carefully there are little people waving in the windows of the Chicago skyline and that’s me and a couple of other people from the office.

Sue Rowe: I loved Tweety; I wanted to do all the shots of Tweety. There is a lovely moment where a character gets hit by the basketball and hundreds of Tweetys circle his head in a classic toon moment. I was having trouble making the image look real—in those days, more than 10 layers in your comp and the render farm would fall over. Simon Eves was fresh to the R&D department and he saw I was having issues with motion blur on all these little birds. He came back a few days later with a motion blur node he wrote himself which worked using vectors; it was fast to render and looked like film motion blur with a soft fall off. Did I ever say thank you Simon? OK, here it is 20 years later!

Bruce W. Smith: There was another sequence where we referenced Pulp Fiction. We had Elmer Fudd and Yosemite Sam in the outfits of Sam Jackson and John Travolta and they pull out guns and they shoot the Monstar’s teeth out. It’s something that’s totally Warner Bros., but it’s something we could never do today. But every time we saw that gag, that gag would just kill. Ivan Reitman always laughed when he saw that scene because it was completely in character with what these guys would do. We didn’t think we could keep it, [so] we just threw it in there, and it would always get the big laugh. And it ended up staying and the beauty of it was that we actually ended up getting the music just because it always got the biggest laughs in the test screenings.

The Space Jam Legacy

Bill Perkins (animation art director): Everybody was looking over the fence and thinking, ‘Oh, it’ll never get done, it’ll never get done, it’ll never get done,’ and then when it did, we felt very accomplished that it was something that was pretty impossible. Fortunately it did make a lot of money because it was one of those things that if it didn’t it would have been a lot worse.

Neil Boyle: When people used to come up and ask me what I did and I would explain what my job was, and they’d say, ‘Okay, what have you worked on?’ I always used to say Who Framed Roger Rabbit first because that’s probably the best-known thing I worked on. And then as the years went by and I’m talking to people who are in their early twenties, I’d say, ‘Oh, I worked on Who Framed Roger Rabbit,’ and they’d have a distant look, and then I’d say, ‘…and Space Jam,’ and they’d go, ‘Space Jam! I love Space Jam! It was my favorite film when I was six.’ And I would feel incredibly old suddenly.

Allison Abbate: I did work on Looney Tunes: Back in Action a fair few years later and I think it took that long for them to desire to do another one of those movies. But when Space Jam was made, I think there was a love for those characters and the stores became really popular. So it felt like we were feeding a great collective unconscious love for these characters. By the time Back in Action came around, it was waning and it was a mad dash to get that back.

Roger Kupelian (computer character animation, Cinesite): All said and done, Space Jam was where I met a lot of friends I still work with today, and it was my first actual vfx credit. I’m still amazed at how people light up when I mention it. Often it gets more of a reaction than mentioning my work on the Lord of the Rings trilogy. I guess the film holds a special place and did some real magic.

Bruce Woodside (supervising animator): It was a surprisingly stress-free and, dare I say it, fun experience, though I’m sure others remember it as a Bataan Death March of long days, sleepless nights, carpal tunnel, and too much pizza and coffee. Working with Ivan at Northern Lights on the Universal lot was easy and often enjoyable, and the animation directors as well as the knuckle-headed executives were too distracted by the larger issues to mess with little us. We got our work done, and the picture came out on time and made fistfuls of money. It may even have—momentarily—filled the shelves of the ill-fated studio [WB] stores with tie-in merchandise.

Bruce W. Smith: It was a great time in animation. Disney was kind of still the only game in town – I think Dreamworks was just getting themselves off the ground. Space Jam represented the polar opposite of what Disney was doing, which was musicals mostly. We were proud of being very different at the time. It showed that animation can actually do other things besides sing to you. We serenaded you with lunacy.