The Oral History of ‘Space Jam’: Part 2 – The Perils of New Tech

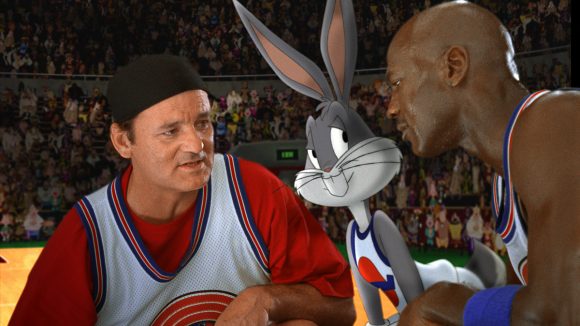

In Part 2 of our 20th anniversary of Space Jam oral history, members of the original animation and vfx team discuss tackling new techniques for 2D animation, and gearing up for the visual effects.

Old Meets New in Animation

Bruce W. Smith (animation director): Once all the live action was shot, Tony [Cervone] and I spent a great amount of time in the editor’s room translating a lot of how our storyboards would work against the existing shots, because sometimes Joe [Pytka] would just create stuff on the fly. I actually prefer that sense of spontaneity that Joe did so well. The editor, Sheldon Kahn, had to deal with a lot of just greenscreen shots and try and work out how to tie together the continuity based on storyboards we gave him. And then Tony and I would go back to the studio and re-board based on one of Sheldon’s cuts.

Tony Cervone (animation director): Our animation unit was in Sherman Oaks. Animation would come in from around the world – London, Toronto, Ohio. We would have sweatbox sessions, like director reviews, where we would go over the animation and make inputs and suggest notes. Some of us traveled a bit – Bruce and I went to London a couple of times.

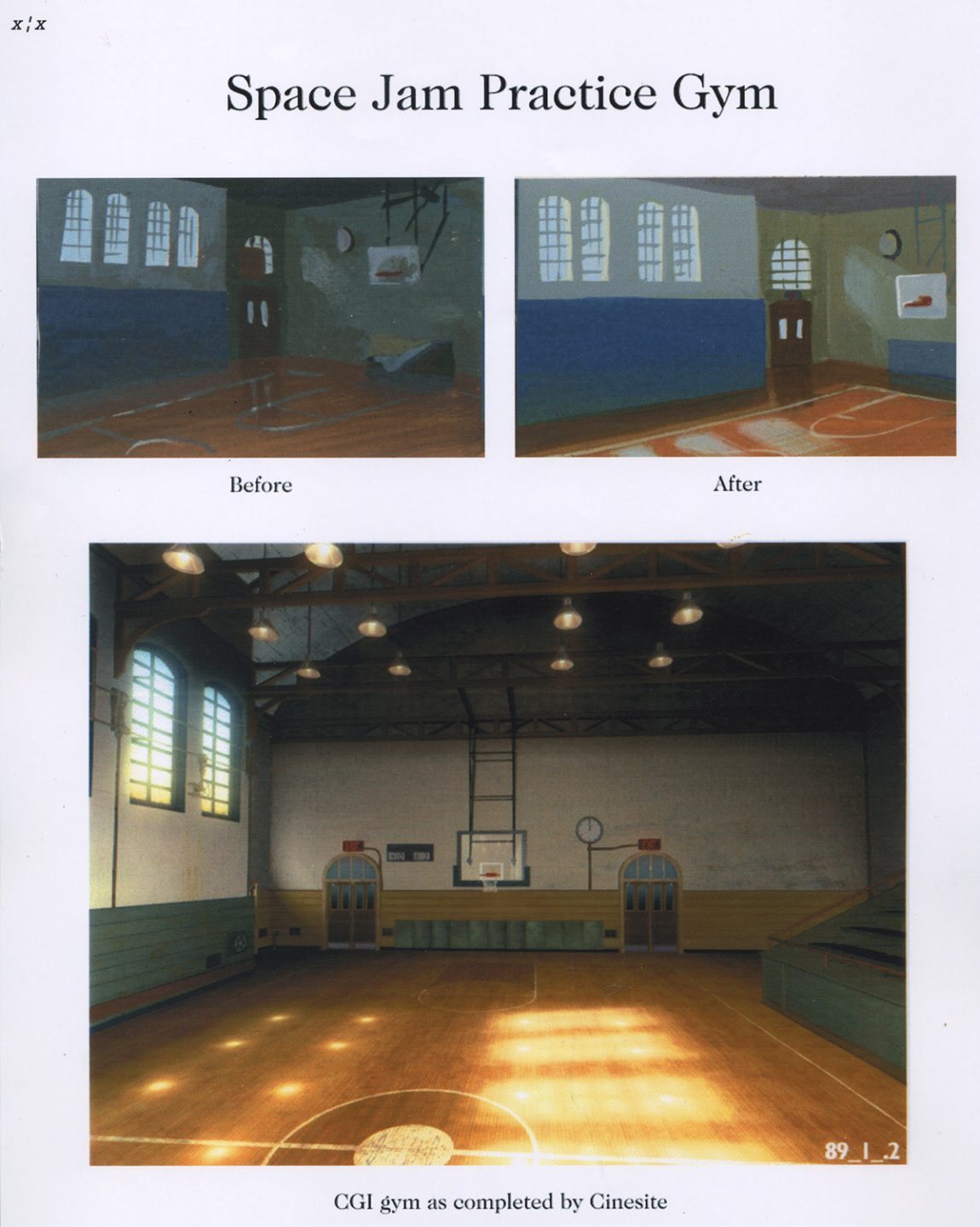

Bill Perkins (animation art director): To do the animation, we weren’t using cels anymore. It was going straight from drawings to digital format, with compositing and some 3D visual effects as well. The feature group and the various animation teams did the 2D animation and 2D effects, and then we sent digital files over to Cinesite and they were composited there.

Bruce W. Smith: But we were still animating on paper. Well, we were still cleaning up these characters on paper, and then from that point everything just jumped into the digital realm. Some of the backgrounds were actually done traditionally and then scanned in to become digital properties, but in the beginning it was all sorts of real beautiful painted backgrounds. We’d take those paintings, scan them into the computer, touch them up, and then separate elements to give you the various depths of field.

Morgan Ginsberg (animator): Aside from just delivering a quality animation quota, one of the challenges was the time consuming act of matching to stats -on 1s- and making sure the characters looked like the characters that we grew up with. We studied – watched – all the great cartoons, and had a library that we could reference, including The Dover Boys that showed up in my crowd scene with the Bull from Bully for Bugs. I’m not sure it was Tony Cervone and company who wanted the different eras of Daffy at certain parts of the movie or whether the different studios just delivered a quilt of multiple models out of choice.

Ed Jones (visual effects supervisor): I was the visual effects supervisor on Who Framed Roger Rabbit. It was a hell of a workflow and a pipeline that had to be built at different locations, with different processes as far as animation to editorial to compositing. All those were in different locations and when we were dealing with Who Framed Roger Rabbit what we had to do was create a manual of all the processes that everyone had to abide by. Things were shot in London on Roger Rabbit, they were then shipped to California, they were divided in California between Burbank and ILM, and then they came back to ILM and we would do some pre-work, what we call photo-rotos or references that would allow the animators to start animating on certain pegs.

Those would be sent back to London and be animated in London. After being animated in London all those physical assets had to come back to San Francisco. It was all assembled via optical photography. So there were multiple layers of intermediate elements, lots of experimenting with Eastman Kodak stock. The technique that created the three dimensionality were the tone mattes that the effects animators did by printing color in a photographic process to give it some dimensionality and then combining all those elements into one final composite.

But on Space Jam, instead of having to go back to photographing layers and layers, we used digital compositing and did all the animation and effects animation as layers, and we were able to save several layers in pre-comps. So it really allowed us to, firstly, finish the massive amount of work, and secondly, to not only layer the animation in a more effective way but combine it now with totally cg environments.

Neil Boyle (supervising animator): We still used the same photostat system that we’d used on Roger Rabbit, which was to blow up each frame of film onto a photostat which you could then very lightly trace in blue or another color onto the drawing so you could figure out where Michael Jordan was, where his hands were, where his eye direction was going, and so on. Then onto those sheets of paper you’d draw your characters and then you could shoot the photostats and the drawings together to get a crude black-and-white line test of how the characters were interacting with the live-action.

Everyone assumes that when you go digital it’s so much easier, but it’s kind of swings and roundabouts. If you go back to the Roger Rabbit days, if you had a character that was standing absolutely still and the camera panned off them, you would still have to redraw every single frame of that to accommodate the camera move. So you’d be animating the camera move even though the character itself wasn’t animated. Obviously in the digital world you can just do one drawing and they would have match-moved the live-action camera move to your drawing, and so that would be done automatically. So in a way that should be an incredible saving in work.

But on the other hand in the Roger Rabbit days you knew exactly what the camera was looking at every single frame. And so if the camera panned off a character you could time what the character was doing, make sure the audience was looking in the right place at the right time, and then as soon as the character was going out of the shot you could stop drawing that character because you knew it wasn’t in view anymore. But when you got into the digital world we weren’t always sure exactly where the camera was because these characters were being tracked into the shot later on, and quite often you had to draw the whole character even though in the final scene you maybe only saw half the character, or maybe the camera would pan off them and you weren’t sure exactly when the camera was on them and when it was off them, so you always had to do a little bit of extra work.

Fraser MacLean (technical supervisor: animation): After creating all the artwork in traditional paper form, it would then be scanned. I came in to help with the digital ink and paint system Animo which was from Cambridge Animation Systems. They were one of the first people apart from Disney, which had the CAPS system, to find a way of digitizing line artwork. The new technology allowed you to flood fill a closed area, so the drawing that the animator did in pencil on paper would be scanned, and then the Animo system would digitize it. So you would have these little pixels that you would see on the screen. And then when you tapped where the pixels were, the color you selected would flood into that area of the white of the eye or the flesh on a face.

And it could also do a self-trace line, so you could color the line itself which was also kind of revolutionary because up until then, as with a Xerox machine, you tended just to have a single color for the outline. But Animo also allowed you to add or to be discriminating about what the outline of an eye looked like. You could have that as blue, hair could have a gold outline, whatever you chose you could do. Animo was one of the first node-based compositing systems. But one of the craziest aspects of it was we comped everything in Animo and then effectively had to pull it apart, FTP it over to Cinesite, and they re-combined it.

Managing The Chaos

Bill Perkins: Getting it done, and particularly getting it done at 18 studios around the world and tracking every shot and every level on every character and so on was pretty monumental. Warner Bros. was trying to develop a computer tracking system at the time, but it wasn’t ready to track our show and we had to be in production. So Allison Abbate and Ron Tippe need a lot of credit for just making it all happen.

Allison Abbate (animation co-producer): There were so many moving parts. There were computers but it was not like it is now where everything is on a spreadsheet. It was Ron’s idea to put everything up on cards and we had it all over – every hallway, every cubicle wall – and we would turn them red when a shot was done. It was also to help make the crew excited, to show them it was being finished. Otherwise it feels daunting and impossible.

Bill Perkins: We had one big room that had a colored card for every shot in the movie going around the whole room, and it was like being inside a computer. You could see where everything was, and it was color-coded by studio and what department, and we would shuffle these things from department to department. So you could see exactly where everything was, in what studio, in what phase it was in. It was pretty remarkable.

Fraser MacLean: They were using the same machines for the night crew on ink and paint that they were using to render the elements, but there was no render management tool. There was an attempt all the way through to create software that could supervise the rendering, but often we would be there at two in the morning watching for a single frame to fail on the render. Sometimes we would have to shut everything down and run up to the eleventh floor and reboot all the machines by hand. So a lot of it was kind of a stampede of the last death throes of the analog process, and the kind of birth pangs of the new techniques in a horrible kind of electric soup.

Wait, There Were Miniatures In Space Jam?

Evan Jacobs (miniatures): We had just formed our miniatures company Vision Crew Unlimited when we were approached by Pamela Easley, the vfx producer for Space Jam, about providing some models for the film. They wanted to use the miniatures as a bridge between the ‘real’ world and the animated. We ended up working on a model of the Great Western Forum stadium wrapped in fabric, referencing Christo’s wrapping artworks and a rooftop cityscape which ended up being a transitional element from a press conference scene.

We also shot some retro-futuristic space ship elements for the film, repurposing some ships originally built by Boss Film Studios for a Philip Morris commercial. Originally, there were some other things planned but they were eliminated from the final script. One of my funny memories visiting the set during shooting was that Joe had the PAs carry a full-size basketball court to every location. At least that’s what we’d been told. Pytka is a very tall guy and evidently enjoys playing basketball, so they had guys to shoot hoops with in between set-ups. It was a pretty unique environment.

Cinesite Gears Up

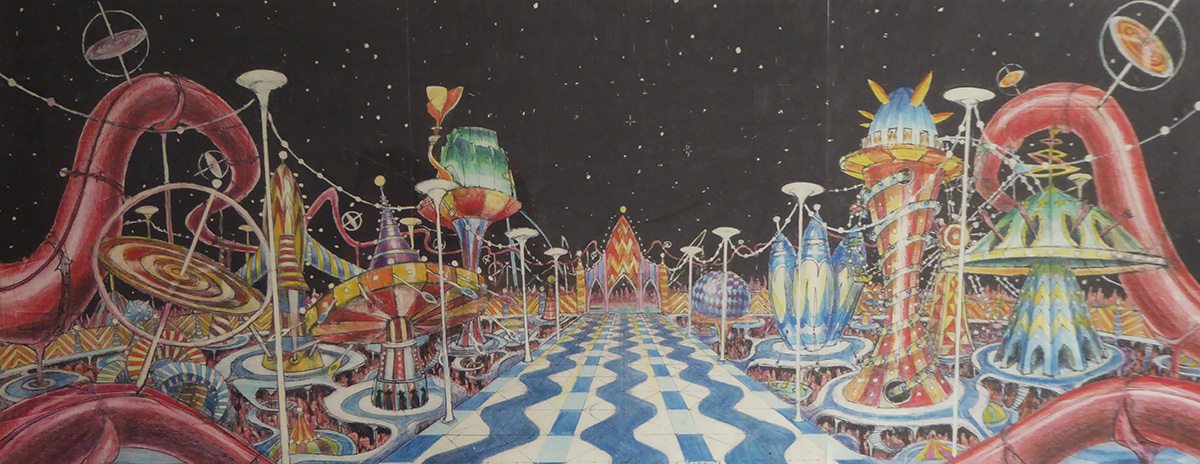

Carlos Arguello (digital effects supervisor, Cinesite): Cinesite had offices in London and L.A. I was doing all the design in London so I would fly to London for ten days and then come back to L.A. another ten days, and I would fly to London again. And so forth. It was a pretty crazy schedule. I was in charge of all the digital design—the shots when Michael Jordan goes into the hole, when his hand gets extended, any 3D characters, their environments, anything that was designed in computers. Doug Tubach [digital effects supervisor[ was responsible for all compositing.

Roger Kupelian (computer character animation, Cinesite): Having experience as a storyboard artist, I was hired to be part of Carlos Arguello’s concept department over at Cinesite Hollywood. Cinesite was at the forefront of developing some serious software for vfx. What I did, however, was much more traditional. I would use standard mediums to execute the work and then scan it in and finish in Photoshop. Computers were slower and crashed often back then. We lost a lot of time re-doing work. You could go get coffee after hitting the save button. Eventually, I learned to use other SGI-based software to augment the art, and in fact ended up ‘flip book animating’ background characters for the big stadium scene at the end of the film. I also worked on ideas and digital elements for the flight to Moron Mountain, Jordan’s being sucked into a rabbit hole during golf, Stan being squished flat, and many many other parts of the story.

Carlos Arguello: It was the first time we had frame-by-frame projectors, and we would go literally frame by frame making sure that everything was perfect because it was all new and we were always looking for technical flaws.

Jonathan Privett (CG gym design, Cinesite): Strength was required as Cinesite in L.A. had one of the first ‘stop frame’ projectors in the world, that meant for the artist an unprecedented and unwelcome scrutiny. We much preferred the good old fashioned run-at-24-fps, just-as-the-viewer-sees-it approach—I still do!

Carlos Arguello: Ivan Reitman used to have a very fancy office in Universal, and it was very fantasy-like for me to go there for meetings. It was my first big Hollywood thing and I’d go to meetings with 25 people. Sometimes, I would come to L.A. only for six hours, and then get back on the plane to continue doing things in London.

Roger Kupelian: The technology was still being figured out. These days we project digital clips, but back then review footage had to be filmed out and played on a loop. I remember those long screening sessions with Ed Jones and his sharp eye. Nothing would escape it. In fact, one of my most terrifying moments was sitting in a conference room with Ed Jones, Ivan Reitman, and Joe Pytka, along with tons of execs, at Reitman’s Northern Lights offices. Remember that this was at a very early part of my career. It’s like a buck private suddenly finding himself in a room with 4-star generals and their entourages. It was a pretty intense meeting as I recall, complete with mechanically closing windows. Thankfully, I was never called to jump in and flesh out any drawings.

Matt Johnson (digital artist, Cinesite): For London at the time, working on Space Jam was huge deal. Suddenly we were doing this big American movie and it was Bugs Bunny and Michael Jordan. And it was working at a scale that we weren’t that familiar with at the time.

A New Wave Of Digital Tools (And Digital Challenges)

Ed Jones: One of the things we really had to solve because of the greenscreen sets and the moving camera was motion tracking. Nowadays motion tracking is integrated into some compositing software. But it was separate then and we came up with algorithms to actually do some motion tracking. We had done a Steven Seagal film, Under Siege 2, prior to that where everything was shot on a train and all the backgrounds were digital backgrounds where we had used motion tracking to deliver those digital backgrounds. So we were already on that path of developing proprietary tools, and that allowed us to think in terms of how to build a process with a moving camera, but for creating virtual environments.

Kevin Lingenfelser (digital composite artist and digital paint supervisor, Cinesite): For the digital paint part of Space Jam we used a piece of Cinesite proprietary software called ‘Ball Buster’ which procedurally tracked and replaced the red tracking markers with complementary greenscreen. The foundation of Ball Buster was our original in-house tracking software. The artists just had to isolate each tracking marker where first seen and the algorithm took over. Some offsetting and touch ups were needed for foreground object occlusions. Prior to Ball Buster we had ‘S.P.I.C.E.’ for frame by frame—i.e tedious—tracking marker removal. It was developed for our first film restoration—Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Matt Johnson: Cinesite had paved the way earlier with its Cineon system but now we were using Inferno and Flame systems. The beauty of these was that you could have all the clips there in a very linear way, and directly and quickly manipulate the scene. And you could even sit in the room with the director or people from an ad agency and do stuff very, very quickly.

I can remember we were experimenting with early vector-based motion blur and things like that, too. This is nothing special now, but we could take the track of the object and see how it moves through the frame, and then apply motion blur to that based on the track curve and thinking, ‘Wow, that was amazing!’ Again, it was very trivial compared to what people do now, but at the time everyone thought they were very clever.

Simon Eves (R&D, Cinesite): I worked on the tool for adding motion blur to the 2D animation, most notably Tweety who was, of course, fairly fast moving. The workflow was that an artist would track some specific points on the sequence of 2D character-on-black that came from the animation house, and I think it was able to take a basic roto shape as well, and then it would generate an interpolated motion vector field which could be applied as a variable directional blur. The field would deform based on the relative motion of the tracking points on the camera, to produce more accurate blur as the character deformed.

In Part 3 of our Space Jam 20th anniversary coverage, we will look at just how Cinesite managed to create their vfx composites, and the crew will talk about the legacy of “Space Jam.”