An Oral History of ILM’s ‘Dragonheart’ On Its 20th Anniversary

Twenty years ago this week, Universal Pictures released Rob Cohen’s Dragonheart. The film about an English knight, Bowen (Dennis Quaid), who meets the last of the dragons, Draco (voiced by Sean Connery), was not a box office smash, but is fondly remembered for its groundbreaking digital character work by Industrial Light & Magic.

While ILM had already ushered in the age of photoreal creatures with The Abyss, Terminator 2: Judgment Day, and Jurassic Park, Dragonheart introduced a new kind of CG character — one that could hold its own with human actors.

Much of that success came down to the vfx studio’s development of an artist-friendly facial animation system called Caricature or CARI, a toolset that was patented and won its creator, Cary Phillips, an Academy Scientific and Technical Achievement award. In this oral history of the visual effects of Dragonheart, which was also nominated for a visual effects Oscar, key members of the effects team jump back two decades to describe the innovations that were necessary to bring the film’s main character to an animated life.

How to make your dragon

SCOTT SQUIRES (visual effects supervisor): I came onto the project after it had been through an early development process already at ILM. One of the tests they’d done was taking the dinosaurs they’d built for Jurassic Park and making the lips move.

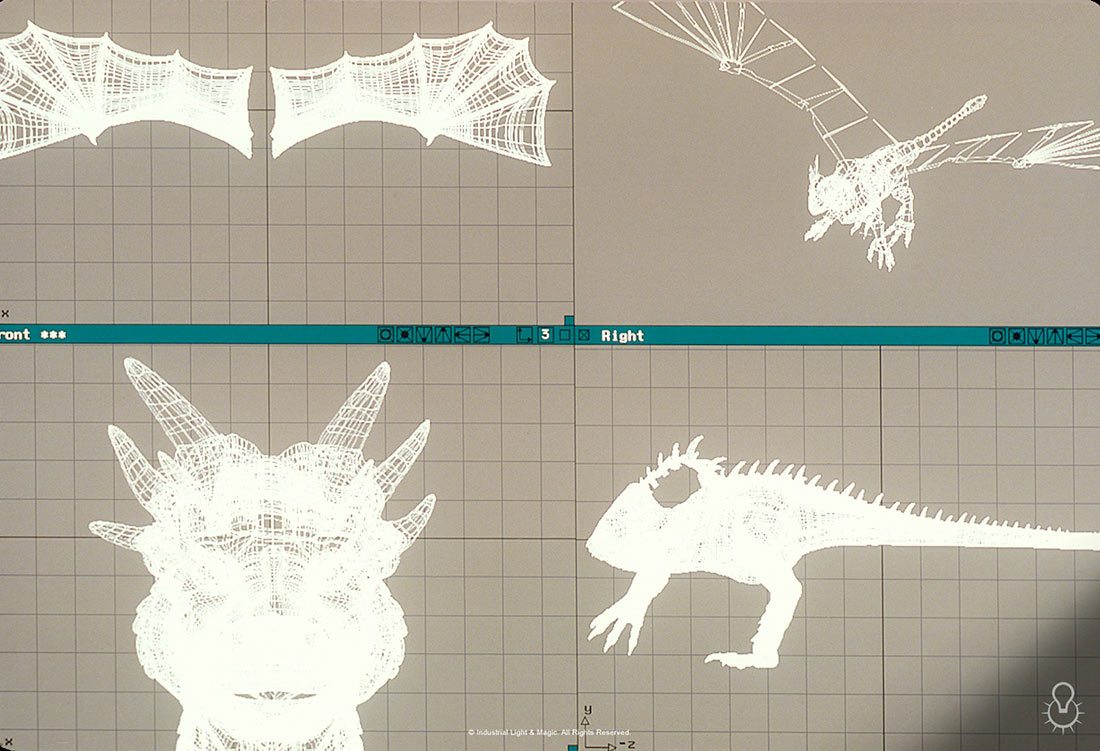

PAUL GIACOPPO (lead digital character modeler): They had animated a T-Rex to make him talk with blend shapes and put pterodactyl wings on it to make it look like a crude dragon.

ROB COLEMAN (co-supervising character animator): Our animation supervisor James Straus animated that himself and that was a proof of concept to prove that ILM could have a talking dragon on screen. They didn’t have a dragon model yet so they took the most complicated model around – the T-Rex – and then they had animated it with Sean Connery’s voice.

SCOTT SQUIRES: The director, Rob Cohen, wanted Phil Tippett to do the dragon design.

PHIL TIPPETT (dragon designer): By the time we did Draco we had some experience with dragons– Vermithrax (from Dragonslayer, the Ebersisks (from Willow) — and a lot of experience with dinosaurs, so we were in good shape. Draco was the first dragon we’d ever done that would be speaking like a human. We had to make a dragon that didn’t look like all the other dragons, plus give the animators something they could work with to accomplish what the script called for.

SCOTT SQUIRES: Phil Tippett’s group made a posable stop motion maquette which looked really nice. I actually took that with me when we shot the location work, which was the whole movie! I took it to Slovakia and for certain shots we would put that in front of camera and set it up for the framing.

PHIL TIPPETT: Vermithrax has a very reptilian face, but for Draco we needed it to be more mammalian so that he would have the ability to show human-like emotion. He needed a tongue, teeth that wouldn’t interfere with the tongue, more muscles in the face, lips that would form mouth shapes to match Sean Connery’s lines. So we decided on more of an apelike facial structure. The artist who did most of the design for Draco, Pete Konig, is a really great sculptor and designer that I worked with for quite a while.

The birth of Caricature

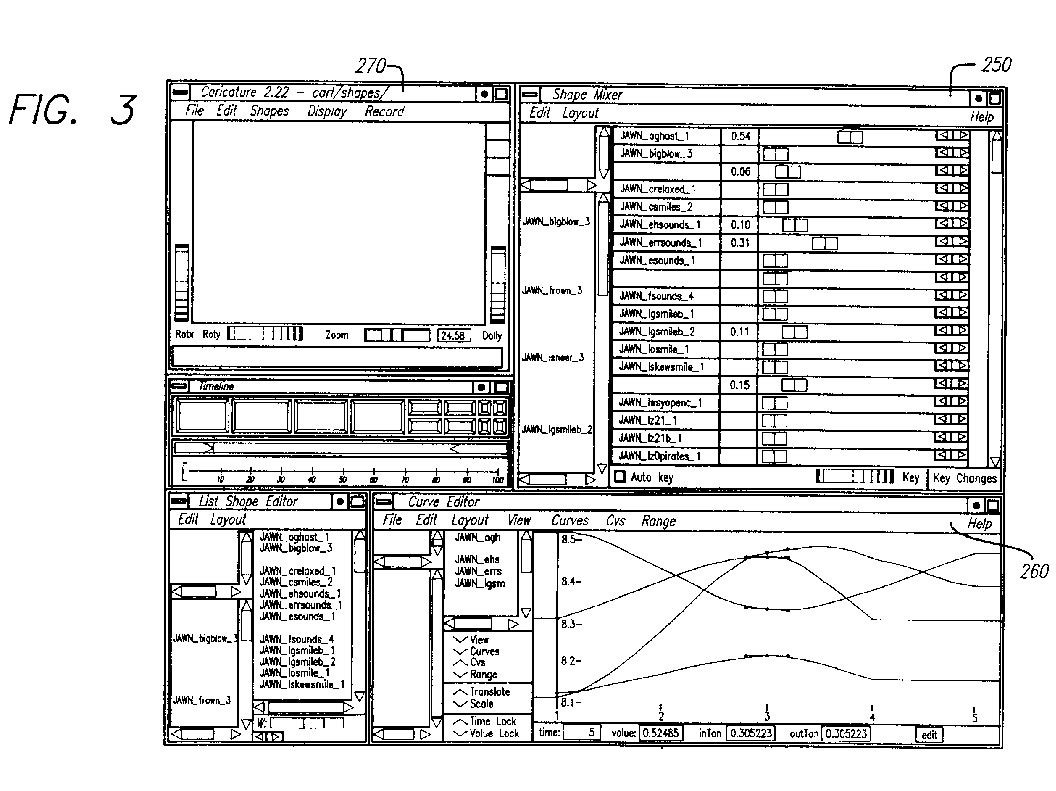

CARY PHILLIPS (animation software development): Christian Rouet, who was the head of ILM R&D at the time, came to me and said, ‘Dragonheart needs a facial animation system. Go talk to Alex Seiden (the visual effects pre-production co-supervisor).’ I went to see Alex and he had made a mock-up of an interface in Photoshop that had a picture of a dragon and some sliders and a timeline and he described to me how he thought this thing ought to work. Two minutes into the conversation I thought, ‘OK I know what he’s talking about – I know what to do.’

PAUL GIACOPPO: At the time we were using Softimage for animation and it had blend shape-type controls. It was limited in its scope and approach but effective on films like Casper which ILM was also working on. But on Dragonheart, we really needed a much more robust system. I remember being in a room one day and they introduced me to Cary who was going to be the guy to write this software to create shapes and a way to animate them.

CARY PHILLIPS: The model for the dragon was orders of magnitude more complex than the Casper model. Casper was done in Softimage and facial animation was being done in the Softimage shape animation system which was really slow and was based on blending of whole expressions – the happy face to the sad face, say, and animators were not able to work interactively. They were typing percentages into text files that they would hand off to a technical director (TD) to run a render, and that was the way they solved their animation. It was incredibly slow and cumbersome.

ROB COLEMAN: The stat we threw around at the time was that Draco’s head was the same number of points as the entire T-Rex in Jurassic Park. Draco’s facial model was so complicated that you’d grab the head and you’d move it and then you’d wait and wait and wait for it to refresh. So Cary was tasked with optimizing this model and the workflow so that we could isolate the head. This is where he created Caricature, or CARI, which was originally just a facial system. It’s still honestly the best facial animation system I’ve ever worked with.

CARY PHILLIPS: To build Caricature, I harvested some software that we were currently using for displaying 3D models. I stripped it down to the bare minimum and started optimizing the display process so it would draw the scene as fast as possible, but also render it as it’s changing. The modern incarnation is a blend shape, but at the time what you’re seeing is a blend of a rest model and a displacement, and a slider attached to the displacement. This was all in the pre-subdivision surface era. These were b-spline control patches.

PAUL GIACOPPO: This is how Caricature worked at the artist level: I would have a model of the Dragon’s rest head and I would make separate files, each sculpted into a different pose. One with the brows down and one with the brows up, for example. Each one of those was its own separate Softimage file and you would have a text file which ran all of those and what you want each of them to be called. The script would convert all of those files into delta shapes. Not only could you animate those controls, but if you made a smile shape that was symmetrical, you could dial in a shape for the smile and there was a secondary slider that allowed you to move it from one side or the other. Asymmetry was the key to make things look organic.

ROB COLEMAN: Basically, CARI let you move an amazing amount of data in terms of sheer numbers of points of the face in near realtime. You’d move one controller normally in Softimage and wait 15 to 20 seconds, whereas in CARI you could grab the movers on the face and they were almost moving in realtime – there was virtually no lag and it was very easy for anyone to use, too.

CARY PHILLIPS: One of the animators on the show, Mike Eames, said to me one day something that still stands out as the greatest thing anyone’s ever said to me professionally. He said, ‘I didn’t realize I had the ability to do this.’ I feel like my contribution was to just make it simple and get the technology out of the way, and give the animators time to work their magic.

PAUL GIACOPPO: One of the things that was amazing about CARI was that this whole system was just designed to load things in and animate faces. But it proved to be such an efficient system that we found we could load the entire dragon in and put shapes on its entire body. It didn’t matter how big this entire thing was but we could now make shapes to make the dragon breathe, flex its muscles and make it do things – all these things that were impossible before.

CARY PHILLIPS: Caricature got extended a lot further for The Lost World: Jurassic Park. We wanted a quick animation review process and a way of rendering out animation takes that didn’t force all the data through the rendering process. So we extended Caricature to the face, body, and multiple bodies as a way of managing all of the creatures inside a shot. ILM has this notion of a ‘shot file’ which is the definition of everything that goes into a scene. Caricature in The Lost World was where that started – a file, a database, everything that goes into assembling the creatures in a scene. Then we used it for The Phantom Menace, which also ushered in cloth simulation inside Caricature.

By the way, Caricature or CARI was not the first name for it. The first name was ‘Fanny’ which I didn’t realize at the time was offensive slang in other countries like Australia so we had to change the name!

Channelling Sean Connery

ROB COLEMAN: The initial design for Draco was that he had this very hard forehead – all these scales on his forehead. Rob Cohen wanted a hybrid between a western (long nose) dragon and an eastern dragon (short nose). The thought on Draco was a shorter nose so we could anthropomorphize it better with a shorter mouth because it would be closer to a human mouth.

But as we started to study Sean Connery from previous films like his Bond work and The Hunt for Red October, we found out pretty quickly that he has an amazing range in his eyebrows. He actually has independent control over them – he will raise one eyebrow and drop it down to the other one. So when we started trying to apply that to the model, these hard scales on his forehead were preventing us from having any movement up there. There was a lot of pushback from us animators saying we need to re-design and get more soft tissue up there – it’s never going to look like Connery.

SCOTT SQUIRES: We’d gathered up quite a bit of material of Sean Connery for reference. As soon as we got the lip syncing work everybody was very happy. And Rob Cohen was very much talking to the animators as if they were actors, discussing the motivation and reason behind the performance. Some of them preferred just being told, ‘On frame 38 can you lift his eyebrow’, but I thought Rob’s approach was much better to help them find the character.

ROB COLEMAN: Connery does this amazing thing where he starts talking on one side of this mouth and goes to the other side. So we were doing that from day one, too. I did the shot where he has his tail trapped in the log and he says, ‘I am the last one!’ I studied clips of Connery and played the line over and over again. He was shot with video doing the recordings, but he didn’t really give us anything in terms of acting or performance. So James Straus cut together a ‘spirit reel’ of Connery which was the spirit of the performance rather than the actual performance. They were facial attitude clips from various films. James would say – this is angry Sean, bemused Sean. It was always about, how do we make the dragon be Sean Connery?

PAUL GIACOPPO: I knew we had nailed it when I was at dailies one day and we were watching the scene where Draco has taken Dina Meyer’s character away and he’s trying to convince her he’s not dangerous and he says, ‘You should never listen to minstrels’ fancies. A dragon would never hurt a soul, unless they tried to hurt him first.’ In this shot, every little beat and eye motion and all the Conneryisms came through – I think I sort of lost it when I saw that shot.

Draco’s other design dilemmas

PHIL TIPPETT: We decided to make Draco a quadruped, meaning he has four limbs plus wings, unlike a lot of dragons like Smaug (from The Hobbit films) whose wings are also their forelimbs. That body shape made Draco stockier and heavier looking than other dragons, so in order to create wings that looked as though they could reasonably support him in flight the wings just kept getting bigger and bigger. Then we had to figure out a physically plausible way that his wings would fold into his body when he wasn’t in flight, without taking up so much visual space that he looked uncomfortable on the ground, or that the wings weren’t bunched up and distracting when he was performing lines with a human character.

PAUL GIACOPPO: We’d get these cyberscans of the maquette that had been made in cylindrical sections and then we’d take them into Alias, our modeling program at the time. The technique was to take the scan, go into a profile view and project curves against the model and then to re-build those curves in a very specific uniformed spline so that they were aligned with each other, then skinning that entire model together into a mesh. Then we did further detailing of it. At the time Alias only had one undo!

SCOTT SQUIRES: There were so many decisions to make about how to move Draco’s body pieces around. Were these hard scales? Were they stretchy? Would his wings fold like that? We were always trying to avoid him looking rubbery.

ROB COLEMAN: There was a huge amount of talk about the flying. Animators Steve Nichols and Mike Eames worked out a lot of the flying. There was a lot of discussion with James Straus about the amount of curve in the wings and the fingers in the wings and how much was flapping versus gliding. There was one very awkward sequence where Bowen’s in the field and Draco’s kind of hovering above him flying and they’d shot it in such a way that we were so restricted in the way we could do it – we wanted to have him swooping around and beating his wings but we couldn’t. That was a scene that we thought was breaking any believability that we’d earned!

Shooting in Slovakia

SCOTT SQUIRES: Ninety-five per cent of the movie was shot outdoors. I spent six months in Slovakia. That was the first project where we used an electronic surveyor’s tool, a transit, to measure the set. We were dealing with large outdoor areas so I had a small vfx crew out there to take measurements that let us do them even half a mile away. I wrote a program for the PowerBook 180 that the transit would plug into and record X, Y and Z points and would automate it into a spreadsheet. We used markers like plastic painted soccer balls all the way down to tennis balls. It would help us with matchmoving and tracking and building up models of the environments. I also had the team make some cardboard cutouts of Draco so we could put those up so the actors and filmmakers could see that.

ROB COLEMAN: There was so much great interaction between Draco and the environment and the characters – I put all the credit for that on Scott Squires.

SCOTT SQUIRES: In just about every shot we tried to connect something physical to what Draco was doing, whether that was air or water or something he was moving. The TDs did some advanced shader writing so all the interactive lighting was tied into the flickering of the camp fire, for example. We also shot elements like flame throwers and fire elements for the flames coming out. When Draco goes into the waterfall, we had a pipe coming out and that was controlled by practical fx – the water would go around it. Then when he dives into the water, we had three 55-gallon drums welded together dropped from a helicopter to make the splash. When he resurfaces we had a black full size maquette of his head which helped with water interaction.

ROB COLEMAN: They had a great practical effects team (overseen by special effects supervisor Kit West). There was this one explosion of all the sticks and fire and we actually saw the real plate and it just kept falling and falling and it was falling forever! Scott was always about blending that in – they had petrol canons and flame throwers. We didn’t do any fire effects digitally – it was all real. We’d blow stuff up here at ILM, which would be composited in.

SCOTT SQUIRES: In the end, there were about three practical Draco shots in the movie. There’s one rubber foot shot and they had built a fiberglass of his side when Dennis puts on the blanket and steam comes out of it. Then ILM’s Model Shop also made a mechanical full-sized mouth that Dennis Quaid could stand in for interaction, which was all hydraulic and puppeteered and we put our CG skin over that.

A film of many firsts

PAUL GIACOPPO: In addition to CARI, another programmer Jim Hourihan was simultaneously developing iSculpt which was this way to sculpt large points just by clicking different parts of the model. It was very much like what you can do now in ZBrush. I had to work during the entire movie without any of this. There was a shot I had to work on – Draco was upside down looking back in the mud trying to lower his brow and it was so strangely in this position that I just couldn’t sculpt it. Somebody said, ‘Why don’t you try iSculpt?’, and I loaded it in and in three clicks I had done what had taken me hours to try to do!

SCOTT SQUIRES: CARI and all the things we did on that film weren’t just a technology thing – we were making leaps and bounds in terms of that, but also in the craft and skill of the animators. In Jurassic we had creature ‘motion’ but on subsequent films the new developments gave us creature ‘expression’.

PAUL GIACOPPO: At one point we were having problems with Draco’s shoulders always collapsing. So we came up with this idea of what if we just made this shape for one shot that was dialed in to fix the problem. It was able to preserve the volume of the shoulder and fix the shot. That ultimately became our first corrective shape and corrective shapes became a big part of ILM – we built our whole digital model shop pipeline incorporating them.

CARY PHILLIPS: There’s so many things that we take for granted – that are part of our normal work, that are the bread-and-butter of animation and visual effects – that were around in such rudimentary form back then. It was just such a gift to be in the right place at the right time and surrounded by these amazing people at ILM.