Malignant Creativity: Robert Morgan On His Shocking Debut Feature ‘Stopmotion,’ Coming To Shudder On May 31

The IFC theatrical and streaming Shudder release, Stopmotion – one word, no hyphen – burst onto screens on February 23, marking the feature film directorial debut of British stop-motion animator Robert Morgan. Born in 1970s Yateley, England, Morgan was already a veteran of thirty years of award-winning stop-motion shorts – including the 2012 BAFTA-nominated Bobby Yeah, about a bunny-eared little fellow troubled by carnivorous larvae and other Boschian creatures.

Stopmotion sprouted from the seed of Morgan’s 2013 Invocation – which starred co-writer Robin King as a Bolex-clicking animator who is subsumed by his stop-motion creations.

“Invocation was a low-budget short we did for Channel 4,” Morgan recalls. “I needed somebody who’d get violently killed, and Robin was up for the task. For years, I’d wanted to make a film about the process of stop-motion animation. I thought it was a fascinating subject for a film to explore the psychological dimensions and the weird, ritualistic, almost occult dimensions of stop-motion animation – bringing things to life and all that. The first idea I had to explore that subject was about a camera that is alive, and the frames were going in and impregnating the camera, like sperm. I played with that for a while, but I realized it wasn’t a feature film, so we made a short. Off the back of that, I carried on exploring the idea and then, with Robin, came up with a more sober exploration of the subject, which is what Stopmotion is about.”

The feature contains three stop-motion shorts within its 93-minute runtime. The first belongs to the protagonist’s mother, Suzanne (Stella Gonet), a veteran stop-motion animator whose arthritic hands make it impossible for her to make frame-by-frame puppet adjustments. The latter two belong to Suzanne’s adult daughter, Ella (Aisling Franciosi), whose animation is a fevered response to her mother’s overbearing nature.

Suzanne’s stop-motion work and the animators’ peculiar monastic work rituals set up Ella’s mother as an archetype of monster animation.

“The main issue,” says Morgan, “was to make a clear distinction between Ella’s work, which is more like my work, and her mother’s. I felt her mother had to be a very credible talent in the world of stop-motion. I didn’t want to make her work seem cheesy. It needed to have its own quality. The idea was to use mythology, and I thought the mythology particularly of the Cyclops was interesting. It also made sense that Suzanne’s thing was to adapt Greek myths, which gave credibility to her art. In the back of my mind, I was thinking it was a bit Harryhausen-esque, mixed with an old children’s TV aesthetic.”

Away from her mother, Ella spirals into a wormhole of creative paranoia holed up in a rundown apartment where a peculiar unnamed Little Girl (Caoilinn Springall) pokes her nose into Ella’s studio, asking Ella to define technical terms – ‘armature’ and ‘mortician’s wax.’

“We needed a playful bit of education, just in case viewers weren’t familiar,” Morgan explains. “The armature reference becomes more macabre later, so we played up that idea of what’s inside the puppets. Mortician’s wax is the thin edge of the wedge that starts Ella down a process of using more macabre materials. It is a real thing that I’ve used in a lot of my short films. And indeed, it was originally used to fix up the faces of dead bodies so that their families could view them. It ended up being used in theater to make false noses. It’s very malleable and looks like flesh but in wax form.”

Stop-motion puppets and creature suit designer Dan Martin’s 13 Finger FX generated characters seen in Ella’s films, which appeared to be constructed of meat and found objects. Puppets were mainly silicone rubber with metal armatures recycled from Morgan’s earlier short films.

“Silicone has a quality to it that looks fleshy,” says Morgan. “I gave a bunch of armatures to Dan and his team, and then he sculpted the puppets. I was very involved in the sculpting and the look of the puppets. You can’t use meat that well in stop-motion because it dries out. It was not very practical when I used minced meat as an experiment on Bobby Yeah, and chicken skin in Invocation.”

The puppets’ livid, sticky look was intrinsic to their material. “Silicone has a sheen to it. And then sometimes I’ll rub it with a bit of Vaseline, which gives an extra sheen. It looks like it’s sweating. Then we added dirt, bits of twig, and earth.”

Ella’s animation featured digital frame capture and Dragonframe animation software, as displayed on the character’s on-screen laptop. “I am a convert,” comments Morgan. “I used to use iStopMotion, but I’ve graduated to Dragonframe. I think Dragonframe is the best tool to do stop-motion. And so, we used it in the film, and even within the fiction of the film, Ella is using Dragonframe – that laptop is my laptop. Ella’s set-up is exactly how my set-up looks.”

Morgan straddled live-action and animated aspects of the production during five weeks of principal photography at 3 Mills Studios in London, working with cinematographer Léo Hinstin, AFC, and production designer Felicity Hickson. Animation proceeded in parallel, with animation director Andy Biddle shooting stop-motion as a second unit. Visual effects supervisor Daniel Karlsson guided digital work through postproduction at Nordisk Film Shortcut in Denmark.

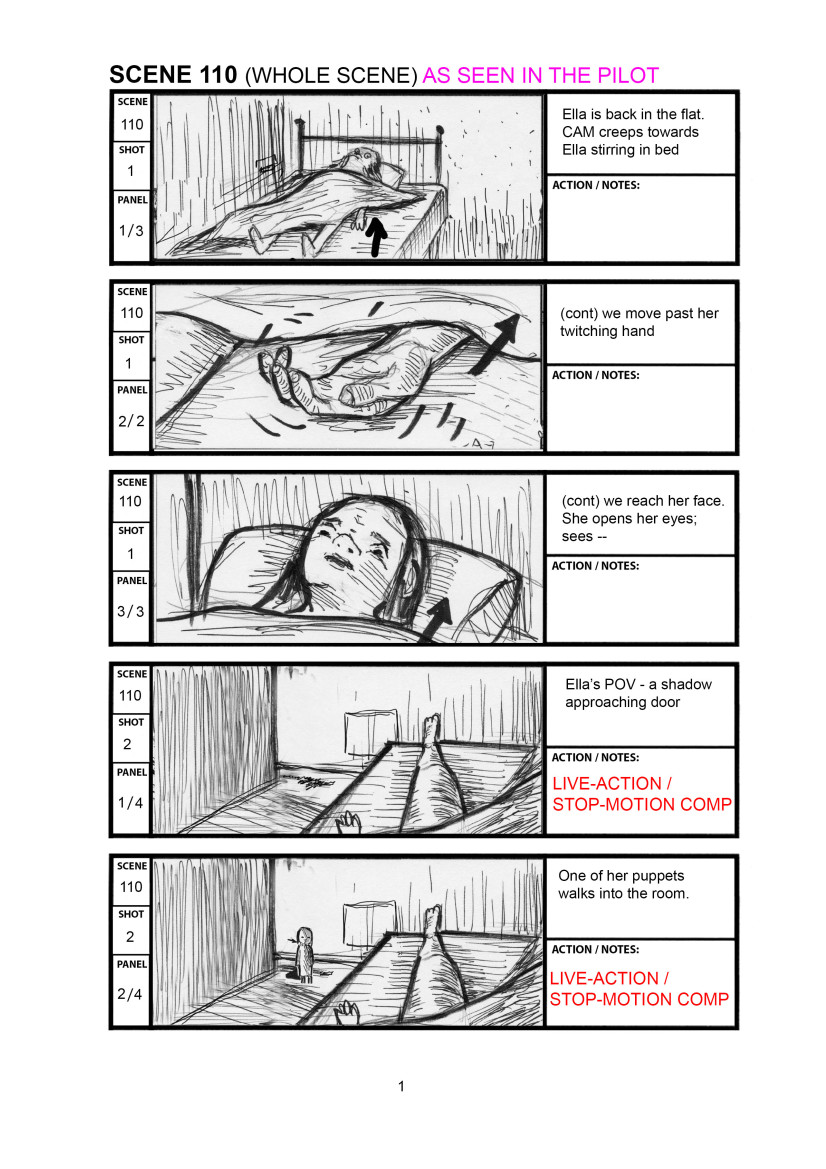

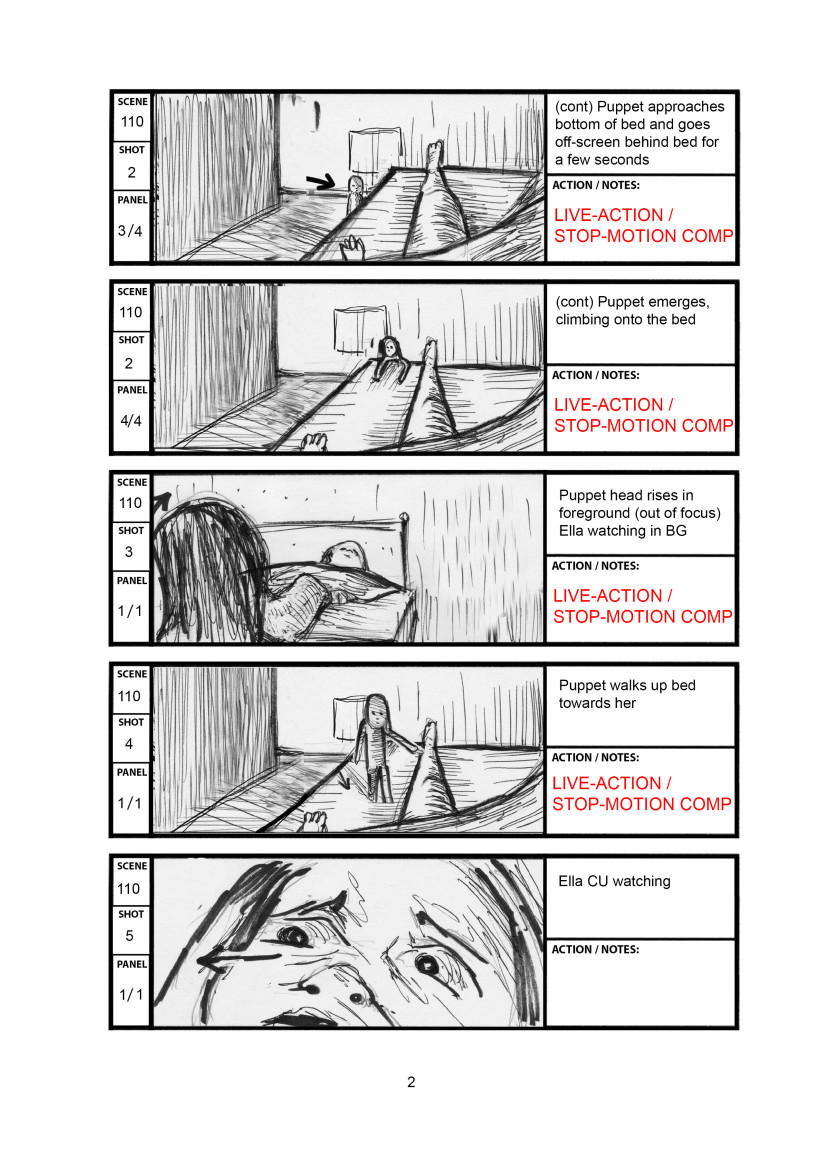

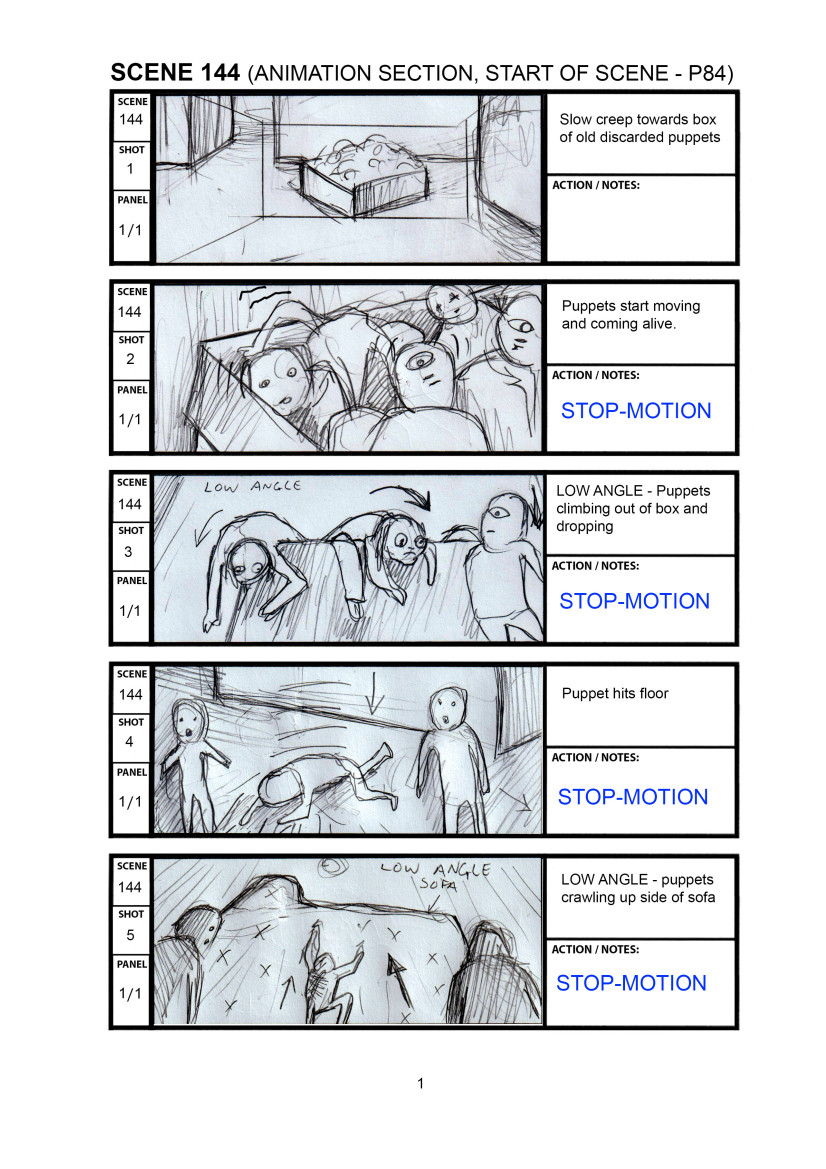

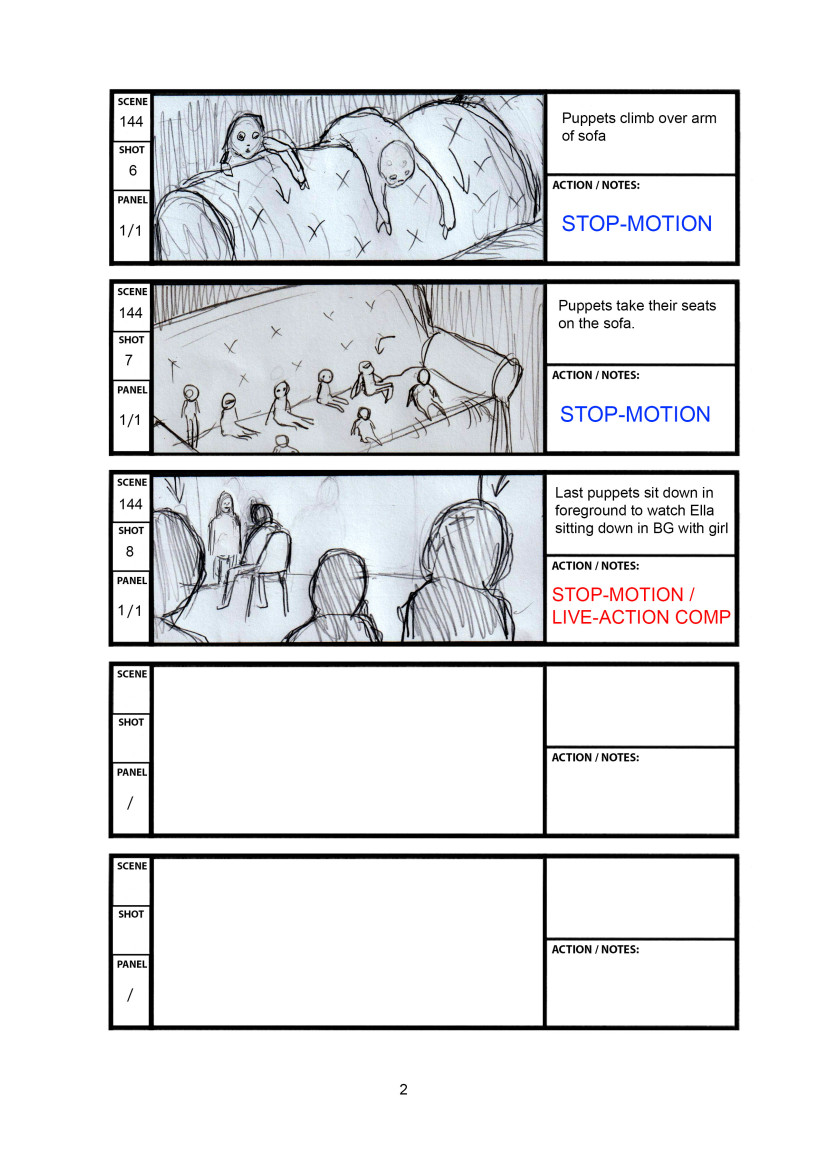

Complexities of the plot, as Ella’s reality blurs and her stop-motion creations intrude on her life, required careful planning to meld animation with live-action.

“When I animate my own stuff,” Morgan recalls, “I don’t storyboard much. I might do rough thumbnail sketches for a complicated sequence. But I tend to shoot and edit as I go, so I can make decisions based on the last shot. With our live-action, Léo and I spent two weeks before the shoot, and we listed every shot in the film. That evolved based on the schedule. Our only storyboards were when there was animation and live-action [combined]. All that had to be shot at the same time as the live-action to create plates that would exactly match.”

“We very carefully storyboarded those scenes and handed the storyboards and the set to the puppet team. They would shoot the puppet plates and then we gave those to the VFX team, who composited them together. During editing, I shot all of the’ film within a film’ stuff in my lounge, parallel to editing. That took about three months. The entire film, from preproduction to delivery, was about a year,” Morgan explains.

Ella’s nemesis, The Ashman, manifests as a misshapen anthropomorphic figure that emerges from her stop-motion set to pursue her through nightmarish dimensions. The Ashman took shape as conceptual art by Dominic Hailstone, which Dan Martin’s team used as the basis for a full-scale suit. Ella crumples into stop-motion as her legs give way beneath her.

“That was nifty editing,” Morgan observes. “We shot the beginning of that on set, and when the Ashman first materializes, during the live-action shoot. When they go through the wall, and Ella runs down the corridor into the weird Yellow Room with the Ashman coming after her, I shot that months later in my parents’ garage in a heatwave.”

Smaller stop-motion figures that creep into Ella’s apartment, clambering onto her bed and occupying other gory forms, featured digital composites of duplicate live-action and stop-motion sets.

“We very carefully storyboarded those scenes,” says Morgan. “The bedroom was a set at Three Mills. But you can’t animate lying on the floor, so we built a full-scale replica of that set, raised off the ground. We recorded details of camera heights and lighting and handed them to the animation team. They recreated everything for a camera set-up in exactly the same place on the raised set and shot the animation. The vfx team then composited the shots.”

Ella’s confrontation with the Ashman leads to a self-destructive showdown where the animator claws into her face, which squishes like wax. Artist Phoebe Stringer created a head cast of Aisling Franciosi and a wax head replica. The art department painted, dressed, and rigged the prop for Franciosi to destroy.

“We had to heat the wax because it dries quite hard,” notes Morgan. “Aisling stood behind it, with her fake head in front of her, and she acted out the tearing. The wax was warm, but if it got too hot, it would melt. It had to just be warm enough for her fingers to comfortably go in.”

The moment climaxes with an abstract vision of an organic blue egg that simmers with mysterious vapors. “I can’t say too much about that without spoiling it,” adds Morgan. “Eggs have certain connotations, don’t they, about hatching? It’s probably to do with creativity. Malignant creativity.”

The disturbing vision of the stop-motion animator’s persona reflected Morgan’s feelings about the solitary and miraculous process of the craft.

“It’s a love and hate letter, maybe,” Morgan remarks. “It’s more about creativity in general. And it’s about my love-hate relationship with the creative experience – how frustrating and soul-destroying it can be versus how obsessive and amazing it can be. The film is about the relationship between being driven to do something and then also feeling like you’re being destroyed by it at the same time. Stop-motion was the perfect vehicle for that. I’ve never seen it depicted before on film. And I hope it gets across the feeling of the strangeness and occultism of the art form.”