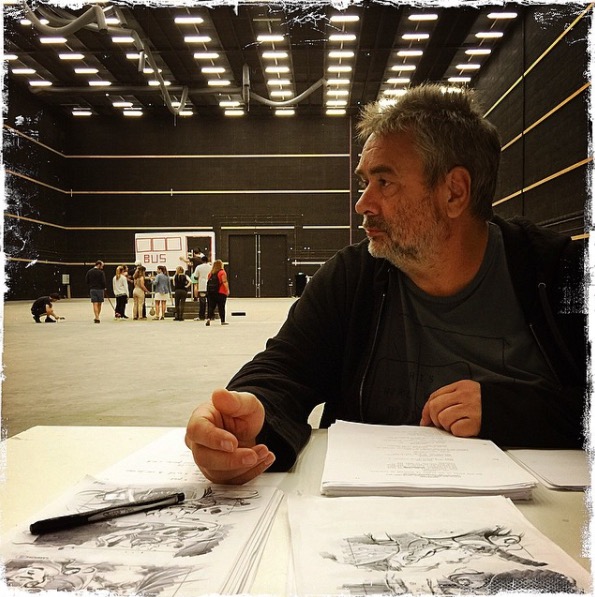

Luc Besson Went One Step Further Than Previs on ‘Valerian’ By Recruiting His Students To Plan Out Complex Scenes

Luc Besson’s Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets contains a massive 2,355 visual effects shots, with many of those made up with detailed creature animation based on motion capture, and the building of entirely synthetic worlds, sometimes even oscillating between inter-dimensional worlds in a single sequence.

To help his visual effects teams – led by Weta Digital, Industrial Light & Magic, and Rodeo FX – get a sense of the scale of his planned vfx for the film, Besson turned to students studying at his own L’Ecole de la Cite film school in Paris to plan out specific shots on large stages (the school is part of the studio where the film was shot).

Dubbed ‘video-vis,’ and made as a pre-cursor to further previs and the actual principal photography, these pre-shoots with 120 students working for around three weeks were a major part of getting everyone on board the most complicated scenes.

Valerian’s visual effects supervisor Scott Stokdyk tells Cartoon Brew how the video-vis was captured, how this differed from the usual previs that tends to be followed on a big vfx film, and what value it brought to the filmmaking and visual effects processes.

Cartoon Brew: How did this video-vis that Luc did with the students actually work?

Scott Stokdyk: Well, firstly, I know other people have done it and I’ve seen it before, particularly with stunt people. But I didn’t personally realize how valuable it was until, well, sometimes in previs there is a little bit of a disconnect where the director isn’t there for twelve hours a day guiding the work.

It usually involves giving notes and going away and coming back. And the benefit of this video-vis was that Luc directed as he did in the real filmmaking, and he had his main editor edit everything together, and it was just a quick version of shooting the movie.

So was it like a rehearsal, or was it more like staging the scenes?

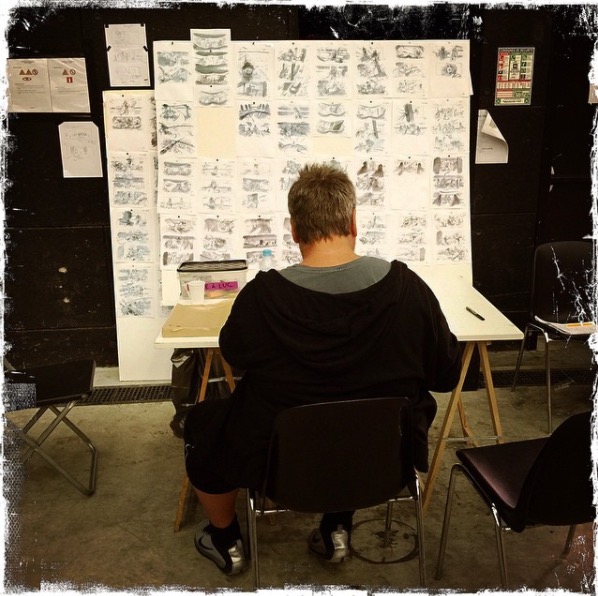

Stokdyk: What Luc wanted to do was teach the students as close to real filmmaking as possible. So he ran it like it was a real shoot, where they would come in each day, and he put all the storyboards up on a big board where they could refer to it, and he went and shot this board-by-board.

He used a single camera and he rigged up some fake dolly rigs to get realistic camera moves. It was ‘quick and dirty’ and the students even brought their own props, and were involved in the process too.

Where was this video-vis used in the film?

Stokdyk: It was done for the big marketplace sequence where Valerian (Dane DeHaan) is in two different ‘worlds’ at once – in a desert landscape and in the market, the part where his hand is stuck in one side. That’s about a 15-minute long scene. But it was used in other parts of the film as well.

After we saw that first batch, we on the visual effects team saw a cut showing how it all worked and it made everything so clear for bidding and for technique, that we were like, ‘This is amazing, can you do this for other sequences?’ And at first Luc was a little shocked and a little reticent, but amazingly he went and did some other sequences for us and it was amazing value.

There was still a lot of traditional previs done on Valerian, wasn’t there? But what benefit did the video-vis bring?

Stokdyk: Luc always knew what he wanted. And when he previs’d something it was basically what we ended up with. But previs is an interesting topic because sometimes a director’s really involved in the previs and sometimes they’re not.

Different directors sometimes are searching for better things to more of a degree than others. And I think Luc is very open to, if there’s a better idea, then he’ll take it. He’s not beholden to his first idea. But he’s also not just always searching for a better idea. He’s like, ‘I have this instinct that this shot works and this cut works.’

So the video-vis certainly seemed like a valuable exercise?

Stokdyk: Yes, and actually, I’ve helped out a couple times with James Franco with the classes that he teaches at USC. It’s a production class with 10 to 15 directors all shooting their own short. And basically he forces every director to go shoot a video version of their entire short film before they shoot one real frame.

I thought it was really sharp of James to make everyone do that. And I hadn’t seen it a lot before that except for stunt people. But it really works – it’s almost like you get a second chance to make your movie after you’ve done it the first time.