Jorge Gutierrez on ‘The Book of Life’ and Bringing Mexico to Hollywood

“Mexico is way more complicated than anybody thinks.”

Jorge Gutierrez talks like a man on a mission. For the past decade-and-a-half, he has sought to bring a more authentic portrayal of Mexico and its people to Hollywood animation.

The efforts of the 39-year-old Mexico City-born Gutierrez culminated last year with his unapologetically folkloric CGI feature The Book of Life, which sunk its roots deep into his country’s culture and traditions. “In the movie, I show you what I think are a hundred of the thousands and thousands of ideas of what a Mexican is,” Gutierrez told Cartoon Brew.

Gutierrez had dreamed of making such a film almost from the moment he entered the animation field. In an interview I conducted with him over thirteen years ago, he told me that he was pitching a CG-animated Day of the Dead feature to Hollywood studios.

The fully-formed vision expressed in Book of Life reflects the mind of an artist who knows and understands intimately the details of the world he has created. Many of the themes and visual motifs, in fact, can be found in Carmelo, the graduation film that Gutierrez made at CalArts in 2000. Produced with a stylized approach to computer animation that was impressively ahead of its time, Carmelo led to a stint on Stuart Little, which was enough to convince Gutierrez to put aside computer animation—at least for a while.

Gutierrez switched to Flash animation where he saw a greater opportunity to develop his voice and communicate his vision to audiences. He created the webseries El Macho, the first of his love letters to Mexican culture, for Sony’s Screenblast. He followed the webseries with jobs in TV animation, including on typically Hispanic-themed Hollywood shows created by non-Hispanics, such as ¡Mucha Lucha! and Maya and Miguel. While working on those shows, he continued pitching and producing pilots of his own inspiration, and eventually landed the Nickelodeon series El Tigre: The Adventures of Manny Rivera, which he co-created with his wife and creative collaborator Sandra Equihua.

Never letting go of his feature film goal, his plans received a boost when fellow Mexican director Guillermo del Toro came aboard as a producer of Book of Life. But not before del Toro turned down the opportunity to hear Gutierrez’s pitch four times, so fed up was he with Hollywood producers trying to cash in on the concept. Upon their first meeting though, del Toro knew he’d found the real deal and decided to guide and support the first-time filmmaker through the feature process.

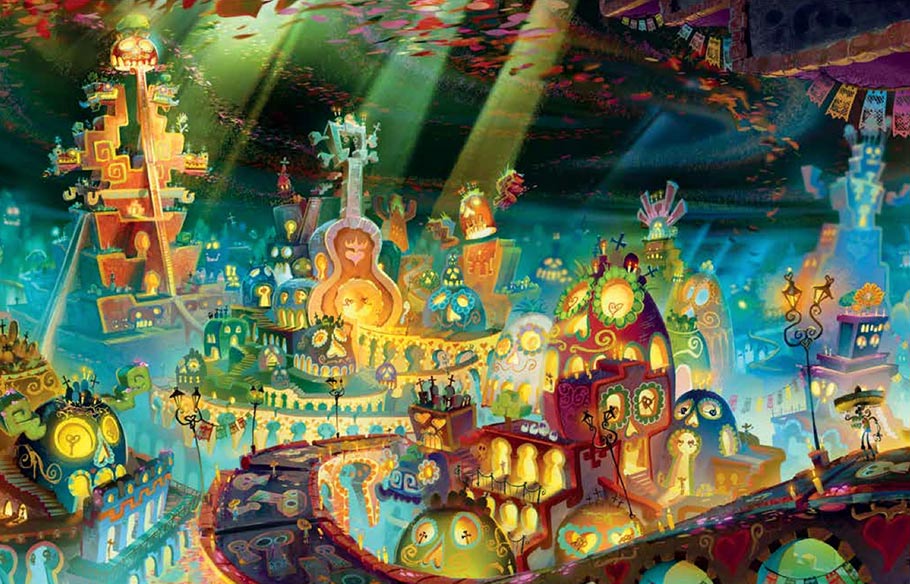

In the following excerpts from our interview with Gutierrez (conducted both by phone and email), he talks about various aspects of the creative process in feature filmmaking. The artwork in this post is from The Art of the Book of Life, which can be ordered on Amazon. Produced by Dallas, Texas-based Reel FX and distributed by Fox, The Book of Life is currently nominated for a Golden Globe in the feature animation category, and contending for five Annie Awards including best film.

Collaborating with Guillermo del Toro

“Working with other people and listening to anyone is very difficult, especially when it’s your first film. I was so protective of everything. But to have someone that I admired so much [like del Toro] telling me, ‘Hey your movie is way too long,’ and ‘Hey, you cannot have a character that does those things in a PG movie—these are R-rated things you’re talking about,’ was easier to swallow. And the other big thing he told me was, ‘You have way too much story. I’m not going to tell you what to cut, but I’m going to be a guide for you.’

“And so it was a true collaboration, much like [Pedro] Almodóvar when he produced The Devil’s Backbone for del Toro. Almodóvar said, ‘I’ll be there whenever you need me, and I won’t be there when you don’t.’ More than anything, [del Toro] really protected my vision and went to battle for me many, many times.

“I’ve always been able to show [my wife] Sandra everything I do before I show it to anybody else. After I showed it to Sandra, I would show it to Guillermo. And if I wasn’t sure about something, I would ask his opinion, and if not, he wouldn’t chime in. He was very respectful. He would always end any critique he would give me with, ‘But you’re the director, and you need to decide what you want to do. And whatever decision you make, I will support it.’ I mean, every once in a while, he would say, ‘It’s your movie. If you want to ruin it, go for it.’ Overall, it was an incredible partnership. What other director of his status and of his body of work is willing to look for first-time directors like me and take them under his wing, and protect them and raise them.”

Shifting from R to PG

“I love Mexican folklore so things were a little darker and a lot more tragic in the end. The original ending was a very depressing ending, and looking back, that was not a good idea. It was one of those things where I always felt, much like the design, I need to push the envelope so that when I pull back, I end up with something I love. So I might have gone too far in the darkness and the violence and the overall raunchiness of the movie. Then, much like El Tigre, you slowly start pulling back and hopefully you end up with something that’s daring. I think if you start in the middle, you’re going to end up with something really watered down by the end of it.”

Research Trips

“Personally I’ve always found it a little ridiculous that animation artists can go on a research trip and think they understand the culture. I never, never bought that. I think you get the tourist version of a culture if you do that. So I said to the crew, ‘No research trips to Mexico. I am Mexico! You guys have any questions, you come to me. This is not a documentary, this is my magic version of Mexico. And I’m more than likely going to lie to you and make up crazy stories, but that’s the version of Mexico we’re going to do.'”

Paul Sullivan, Simon Varela and Sandra Equihua

“[Art director] Paul Sullivan became a true creative partner on this film. You look at the art of book, Paul did so much stuff, and he got in my head. He was one of those artists who was a sponge. I just gave him so many references of so many books and movies. He became so immersed in Mexican culture that we joked with him that if you cut his arm guacamole would come out.

“Our production designer Simon Varela is from El Salvador and he had worked on pretty much every Day of the Dead movie in development at every other studio. I’d always loved his work, but at the same time, I told him, ‘Show me what you did everywhere else because I don’t want to do that. Let’s do our own version of it.’

“Design-wise, Sandra and I have been working together for so long and we did the same thing here. Sandra designed most of the girl characters and I got to design most of the male characters and we went crazy. There was no one above me who was going to water it down. One of things we do is if you want to make a Sandra design look prettier, you put one of my ugly-on-purpose designs next to it so we play off that contrast.”

Creating an animation universe in TV and Feature

“I think they are equally hard and painful but incredibly rewarding. Like giving birth to a baby wearing futbol cleats! I try to have a tragic or funny back story to every building, prop and character. This is my favorite part of the creative process and a part where I can be very subversive with my views regarding the culture and politics of the world we live in today. In both TV and film, my goal has been to create a lived in and worn out world that exists on its own without the protagonist. And usually, and perhaps because I’m Mexican, the worlds I like are morally corrupt and whoever is in charge is usually abusing their power. And it’s up to the leads to challenge and change that world. Or die trying.”

The Evolution of Main Characters Manolo and Joaquin

“Manolo was a lot more over the top heroic and tough in the beginning. Right from he start he had a temper and was a lot more angry at the world. As we kept recording, rewriting and boarding the real Manolo started to emerge. We cut out lots of his lines and made him more thoughtful and stoic. He became someone who was heroic for NOT fighting. For not killing. A quiet and noble heroism. More Zen. His super power became love. My grandfather used to tell me that a macho man can fight any man. But a super macho? He can walk away from a fight.

“Joaquin changed pretty dramatically when Channing Tatum took the role. I told him Joaquin would have the suaveness of Brazil, the charm of Argentina, the cojones of Mexico—he would be Captain Latin America! In the beginning, Joaquin was supposed to be the jerky high school quarterback antagonist that the town loved. And frankly, he was kind of a dick. Slowly and through the process of boarding and recording, the heart of Joaquin emerged. He became incredibly endearing and vulnerable. Like many of the actors, Channing improvised a ton of stuff that’s in the finished film. His evolution is one of my favorite things in the film.”

Environment As Character

“Definitely the hardest thing in the movie was making sure everything read. One of my favorite all-time movies is Nightmare Before Christmas. To me that’s one of those movies where the environment is a character and they’re just as stylized as the characters, yet they work so well together. That was the mandate from the beginning: I want to be able to take all of the characters out of the movie and this world is a character. Every image is going to tell you something; it’s going to be in a way, a moving painting. We had to art direct this thing to a tee.

“A standard frame for us was busy and baroque, so we had to really help the audience focus where they’re supposed to look. For example, with Manolo, his body is so busy, the only place that’s clear is his face so naturally your eye goes there. That’s what we did with everything; we used the chaos to help you guide your eye. Same thing with color: if it was all colorful the whole time, I think your brain would explode. So we had all these desaturated moments, all these dark moments, all these moments with no color to balance things out.”

The universal nature of storytelling

“From day one, I felt the weight of all of Mexico behind me, but it’s sort of a weight I’m used to carrying. That’s what I’ve always done in my career; I’ve always wanted to showcase my culture. One of the things I did early on was I looked at all my favorite movies from all over the world, everything from Seven Samurai to Amélie to City of God, and I realized that while these movies could not be more specific to their countries, the messages, themes, and emotions were incredibly universal.

“I felt even though Book of Life takes place in Mexico, and even though technically all of these characters are Mexican, I’m going to tell a story that has a universal appeal by keeping the emotions really grounded. The eternal struggle of an artist who the whole town doesn’t believe in, and the struggle of someone who wants to change his family and the cycle of something that’s been happening throughout generations—that’s everywhere.

“The songs are the playlist of my life. For example, the Elvis song is my grandparents’ favorite song; there’s a Rod Stewart song in there that my dad really likes; ‘Creep’ was my anthem when I was in high school. Whenever I go to karaoke that’s the one I sing. So all these songs had a personal meaning to me. And I grew up on the border so it’s not like I only listened to Mexican music. I listened to music from all over the world, especially the US and the UK. For me, that’s Mexico, we’re going to take these songs from other countries and we’re going to give it a twist.

“And you’re going to hear a bolero-grunge version of ‘Creep’ and a ranchera version of ‘I Will Wait.’ In the beginning, everybody asked, ‘Why are you casting Ice Cube?’ and ‘Why is there a Biz Markie song?’ And I’d say, ‘I love hip hop. I’m Mexican. That doesn’t mean I can’t like other things.’ This movie is really who I am.”

.png)