INTERVIEW: Sébastien Laudenbach On How He Created A Masterful Dark Tale, ‘The Girl Without Hands,’ Entirely By Himself

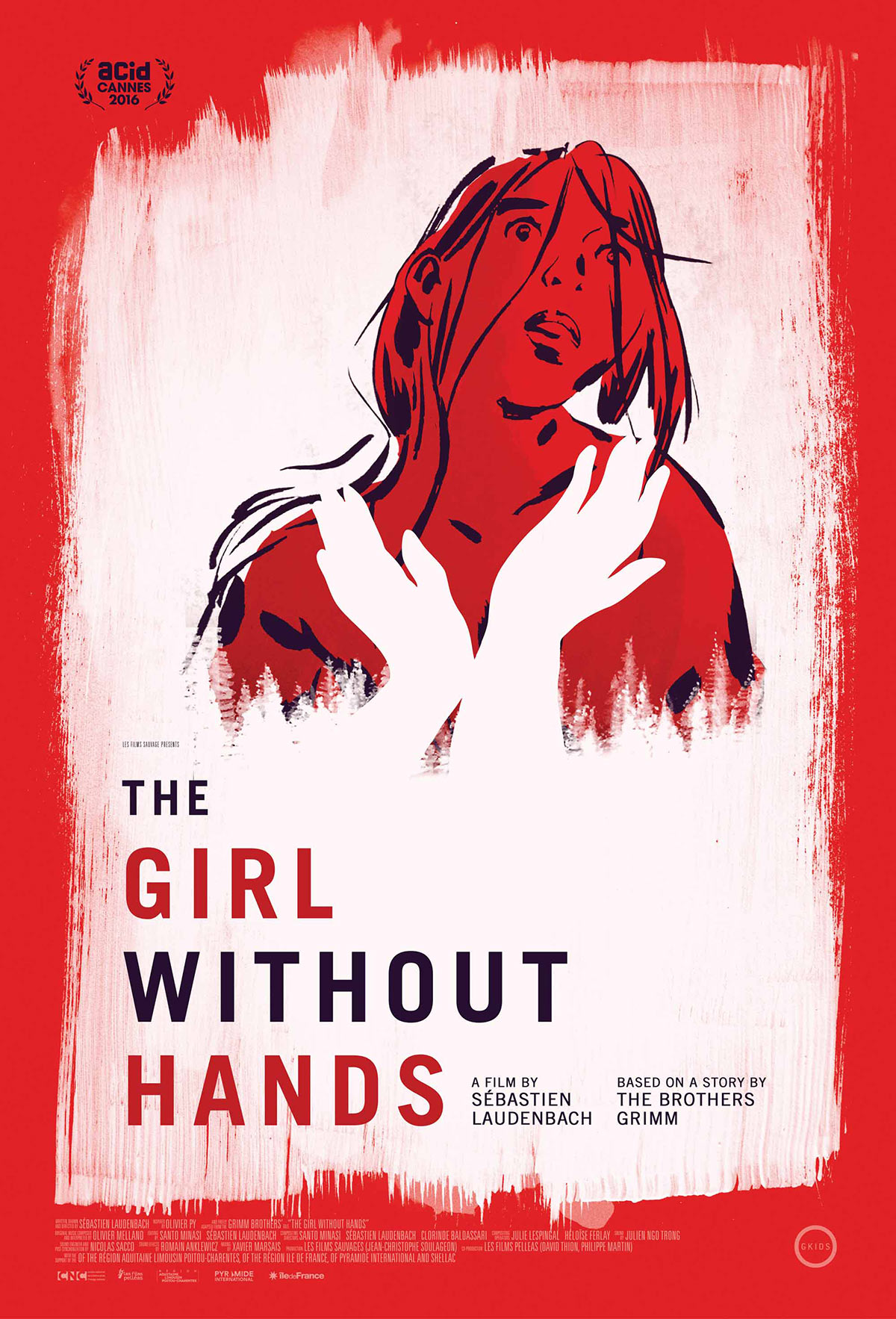

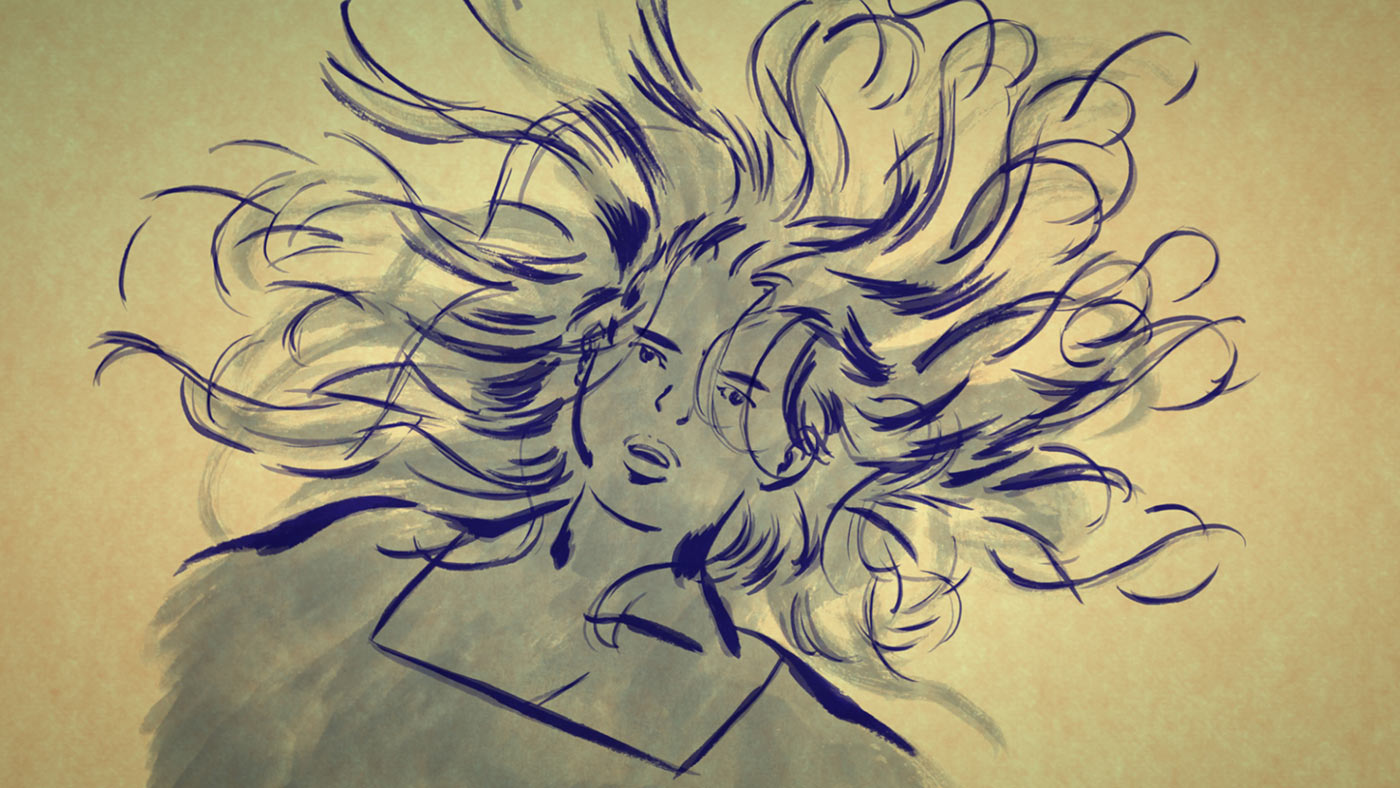

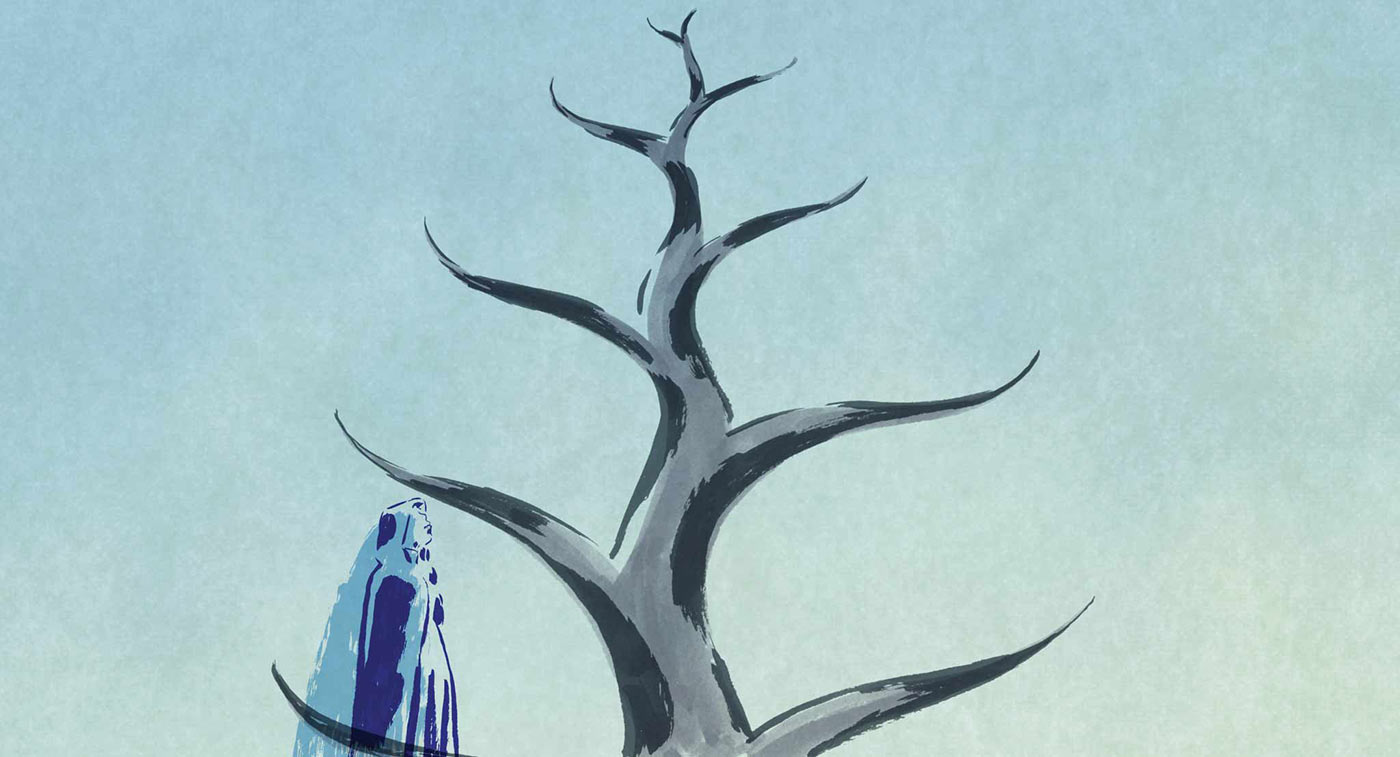

Amongst the current wave of European animated features pushing the envelope is the French film The Girl Without Hands, a haunting adaptation of the Brothers Grimm fairytale. Its stunning hand-crafted visuals arrive in New York today and Minneapolis on Sunday, before expanding to other U.S. cities in August.

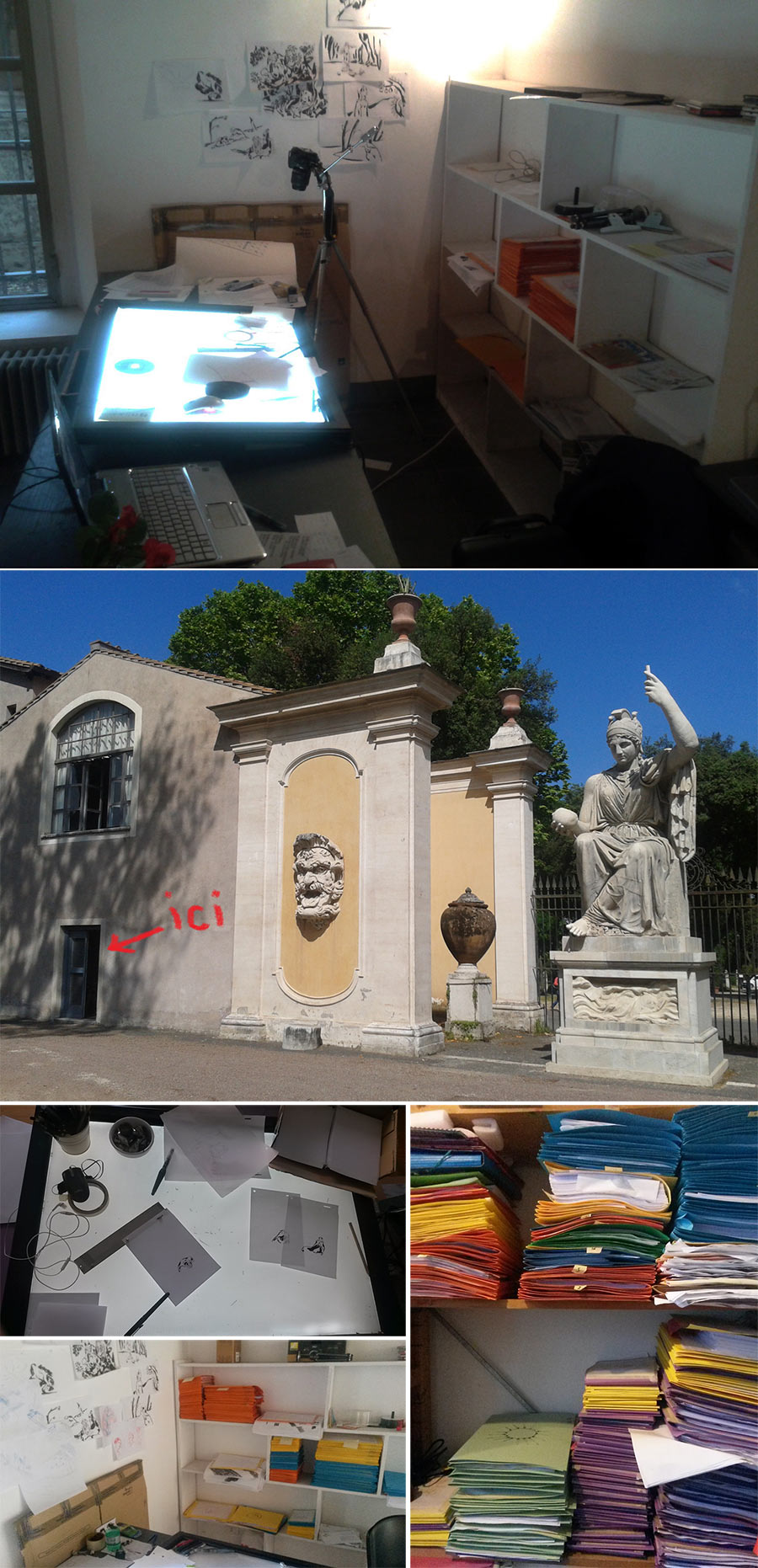

In an unconventional process, director Sébastien Laudenbach animated the film entirely by himself. Thanks to a French residency in Rome, that his wife was admitted to, Laudenbach had one year to do anything he wanted. Previously he had animated the 12-minute short XI. La Force in 10 days, so the experienced shorts director figured it might just be possible to do 76 minutes of animation in one year.

Laudenbach didn’t see the filmed results of his animation until he returned home to France after his year in Italy. He then spent an additional two years animating the remaining parts of the film, and with a small team, composited it all together. The 76-minute film premiered in 2016 as part of the ACID program in Cannes, before screening to acclaim at other festivals, including Annecy, Seattle Int’l Film Festival, Istanbul Film Festival, and Bucheon Int’l Animation Festival. It was nominated at the César Awards last year for best animated feature.

Cartoon Brew spoke with Sébastien Laudenbach at the Anima festival in Brussels, about expressing feelings through lines, offering your audience freedom, and his exploration of cryptokinographie (a.k.a. the art of animation that only takes on its meaning in motion).

Cartoon Brew: As crazy as it sounds for a feature-length film,The Girl Without Hands was largely improvised, correct?

Sébastien Laudenbach: I drew the film from the beginning to the end, without any line testing, so without seeing the results. Only at the end of the first month I shot the first sequences to see if the style worked, to see if it was okay for me. For the rest of the residency that I had in Italy, I drew and drew and drew…it was insane.

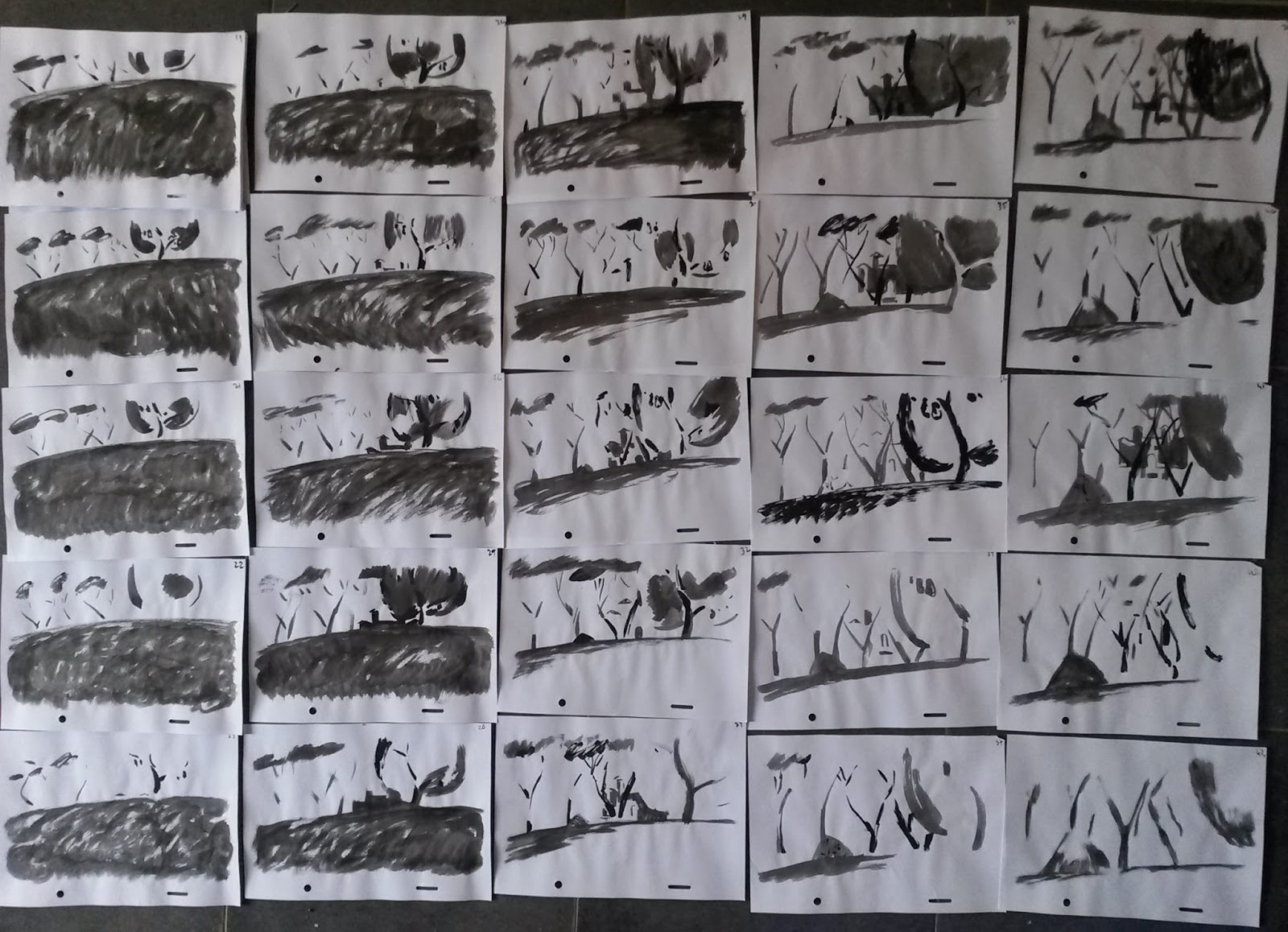

This way to make an animation film, I think it’s visible in the end. Because it’s very much based on sketch, the movement of the hand. There is a kind of energy. Also I worked with music on; I was in kind of a trance. Different kinds of music – like electro pop music, French bands, like Sexy Sushi. Each day I began with this song ‘Je Refuse De Travailler,’ which means, “I refuse to work.”

GKIDS is distributing the film in North America. What kind of American audience do you think could connect with the film?

Sébastien Laudenbach: We’ll see, I don’t know…In France the target audience was from 8 years old [and above]. When I told that to GKIDS they were like, “Wow, no, that’s not possible.” I remember [Kirikou and the Sorceress director] Michel Ocelot said that the job of the kids is to understand the world. And I like the idea to propose a film for kids that is not for them, but they can reach it…A film for kids, for me, should not be at the same level, but a little bit higher. Because kids need to understand and to learn.

The way you animated the characters, with their lines fading when they breathe heavily, and using rough, aggressively-drawn moving holds to express anger, is almost closer to the art of painting than to live-action film…

Sébastien Laudenbach: Yes. Actually, when I returned to France, shooting the drawings to see what I’d done, it was a surprise to discover everything…and I thought that this way of animating was a kind of graphical writing. The film taught me some beautiful things. An important thing for me is when you do animation, you don’t have any of the skin, you don’t have the eyes, you don’t have human beings. You only have drawings, or puppets, or materials…In The Girl Without Hands I saw that, for instance, the characters breathe with the lines, not with the chest. Because my girl, she has no chest; she has lines and colors.

In animation there’s no human beings, but you have a huge palette to express a lot of things and sensations and everything. And I think that when you make a short film, you use this palette, this rainbow. But when you do feature, this palette is more tiny. The cinematographic language doesn’t use the whole rainbow that animation offers, I think.

What’s your thought process like while animating this way? Did you decide on a set of animation style variations upfront?

Sébastien Laudenbach: I don’t decide anything actually; I think that this film decides for me. But it’s not a good answer. [laughs] The fact is, I was in the film when making it. I was seeing the film and drawing it at the same time. So I felt the film.

When the girl has to be dirty, because the devil wants her dirty, the problem was that my lines are already dirty. I didn’t want to animate, I don’t know, some scratches – I wanted to find a way to make my drawing more dirty than they were. So I thought, maybe I can explode it, make it like there’s no shape…When I saw [the recorded animation], it was like, she’s dirty, but she’s also troubled. So at the beginning it was a way to show how dirty she is, but in the end it was a feeling. It is an intimate trouble more than a dirty skin. It was very interesting, but it was not thought out before. It was one of the things the film taught me.

Your animation method for this film is quite unconventional. Can you explain its approach?

Sébastien Laudenbach: The key frames are full, and the inbetweens are partly empty. In some drawings there’s quite nothing.

This ‘cryptokinographie’ is a way to make an animation using limitations. The purpose is to do an animation of a figure, and in each frame you can’t see the figure. For instance, you see a cat walking, but if you press ‘pause,’ there’s no cat. So only movement gives the sense of [its meaning]. I was very interested in this limitation. It makes me free thinking about this cryptokinographie.

In your view, what is the beauty of minimalism in animation design?

Sébastien Laudenbach: Minimalistic – what does it mean? Because there’s a lot of ways to do minimalistic design. The Girl Without Hands is minimalistic, but it’s rich. It’s not empty, even though there are a lot of holes and blanks…I’m focused on the essence of the movement, and the essence of the shapes. I leave a lot of space for the audience, so the audience has to dialogue with the film as to enter it, as to occupy this free space.

I think that it’s the same for the story, because it’s a fairy tale. The strength is this free space. I let the audience be free.

What can they do with this freedom?

Sébastien Laudenbach: I don’t know; anything they want…As a spectator I want to feel when I see a movie. I don’t like movies that bring me by the hand and explain everything to me. I need to be free. With movies, but also with art and books in general.

Speaking about the audience, are you happy with the responses toward the film up until now?

Sébastien Laudenbach: Some women told me, “You know, the girl without hands, that’s me. You told my story.” And it moved me, obviously. I’m very happy with this kind of reaction, because I myself was moved by this fairy tale. Because I am the girl without hands as well. But I’m also the prince, and I’m also the miller, but not the devil… But I’m also the trees… Maybe that’s why I can’t see the film. I’ve never seen it. Even when I was in Annecy, the French minister of culture was in the theater to see the film, so I had to be there, but I [had my eyes closed] during all of the screening. Watching the film is like seeing myself in the mirror. Obviously, The Girl Without Hands is the story of a girl, but I think it can talk to men; it can talk to the female part in everybody.

Why did you find it important to re-tell this fairy tale?

Sébastien Laudenbach: For me the most important thing is to be free. And this fairy tale told this. When I read it, I liked the fact that this girl has to go away from this man’s world, to be alone, but only for a time, only for a moment, to exist completely, to be full. And that she chooses again the prince, even though the prince is quite clumsy. He’s in love, but he doesn’t see this girl as she is, and as she would like to be. He offers her some jewels – the golden hands to me are jewels – so it’s futile. She doesn’t need jewels, she needs to be herself.

But even if this prince is clumsy, she can choose him. Because you can love a clumsy person. So I like the idea that this girl, this woman, chooses this man. For me this tale tells the fact that it is better to be a woman than a princess. And that you can be independent and free, and also in love with someone else. That’s why I wanted to make this film.

Animation and fairy tales go way back to the beginnings of the animated medium; what do you think makes them such a good match for animation?

Sébastien Laudenbach: I think fairy tales are a way to understand human feelings. There is a space between reality and fairy tales, because fairy tales are metaphors. And it’s the same thing in animation. There is a space between reality and animation. You have to interpret the world and the reality.

What were the creative challenges of adapting the fairy tale into an animated feature film?

Sébastien Laudenbach: At the beginning the film was more dry…The characters needed to be more present. Because, you know, in fairy tales you have figures and archetypes, and I needed to make them characters with psychology. So the adaptation work was to see how to change the archetype into characters, but maintaining the metaphors. So the girl is still the metaphor of purity and youth, but she has a psychology.

How did your very first vision for The Girl Without Hands look like, compared to how it ended up?

Sébastien Laudenbach: It began like 15 years ago, in 2001. A French producer proposed me to adapt a play called “The Girl, The Devil and the Mill.” It is based on this Grimm’s tale. The project was quite different than it is today. It was a ‘normal’ project, with filled shapes and colors, and everything normal, with a script and a storyboard – everything we had to do to develop a project like that.

The first project was to be made in Folimage (A Cat in Paris, Phantom Boy), with a real studio. It was very different, and less interesting. [Editor’s note: One animation test was produced at Folimage, and two tests at Bibo Films, producer of A Monster in Paris. One of the tests can be seen below.] But we couldn’t find the money to make the film, because the budget was like 4.5 million euros. In 2008 [the film in that form] was completely abandoned.

What was the film’s budget in the end?

Sébastien Laudenbach: Including the development budget of the first project, at the end it’s 415,000 euros. So it’s very cheap. I don’t know if I want to make a film again for this amount. I lost some years of my life. I’m interested in finding some way to [make a feature] with a small team. But I think that when you’re poor, you’re free. So I don’t want to be rich, because I want to be free. [laughs]

If you were to work with a team on your next feature, how would you preserve the artistic approach of The Girl Without Hands?

Sébastien Laudenbach: I don’t know if it’s possible…but I’m not happy when I’m alone. I like people, and I like working with people. So I’d like to try with a little team, giving each of them a responsibility. Because in animation you make a script, a storyboard, and then the animation is the execution of what is planned before. So I’d like to re-introduce the animation in the creative process. Maybe without a storyboard it is possible to work together. But with a little team – with a big team it’s not possible. With a kind of improvisation, a responsibility for each animator.

What are your thoughts on the European animated feature film in general?

Sébastien Laudenbach: I think that in Europe there’s a kind of freedom, and at the same time a kind of shyness with producers and directors and people who make films… They explore only one way, I think; it’s the graphic way. All films are [visually] different in Europe, more I think than in Japan or in the U.S. In France if you take Long Way North, My Life as a Zucchini, Louise en Hiver, The Red Turtle – these films are very different. But this past year has been quite exceptional. These films are also different actually in their way to tell a story. They’re not based on classical scripts and also the themes of the films are quite new, I think.

Animation is very late compared to live-action films… We have a great forest to explore and we’re just at the beginning. I think animation is not a mature art and I think that we are all teenagers. We are in the teenage [phase] of animation. So it’s great because we have a lot of things to do. And maybe the audience is more open than we think. Obviously, if you want to make money, it’s not possible. But if you want to make art, it is. And making a low-budget film is actually a way to explore this terra incognita.

For more information about the U.S. release of the film, visit TheGirlWithoutHands.com.