How ILM Made Those Insane Bending Buildings in ‘Doctor Strange’

One of the most enchanting scenes in Marvel’s newest superhero film, Doctor Strange, is a chase sequence that plays out amongst a mass of twisting and bending buildings in New York City. A team of designers, previs and visual effects artists looked to M.C. Escher-like imagery and an array of fractal and Mandelbrot patterns for inspiration to help create the chase.

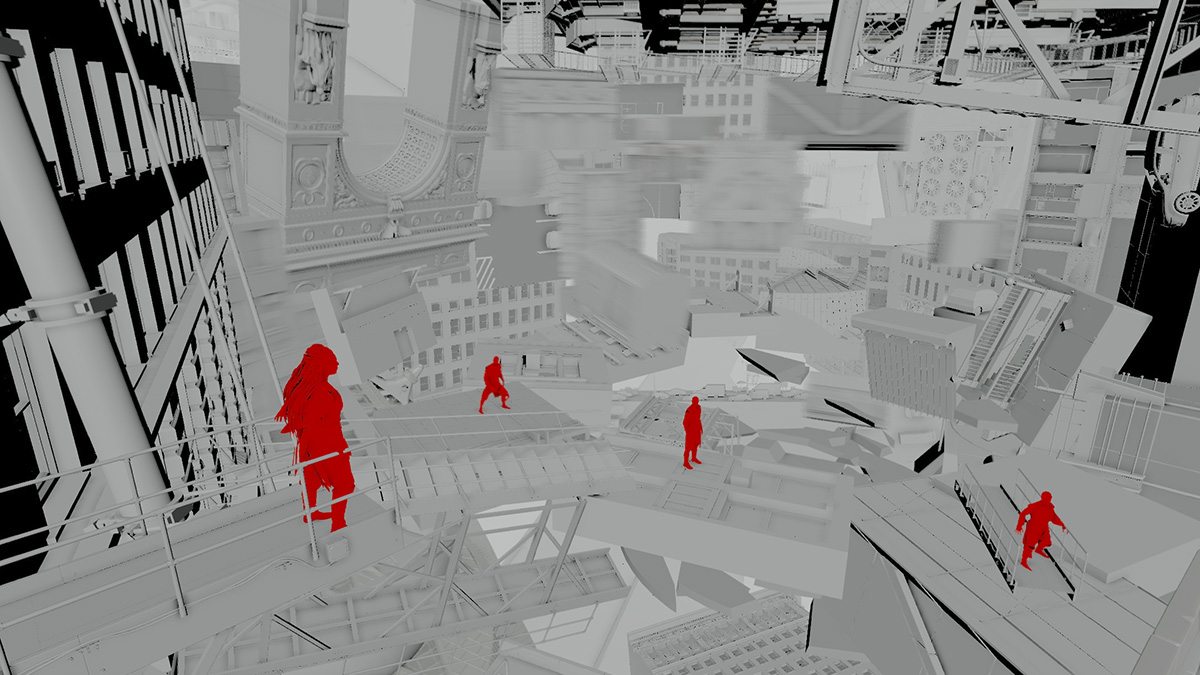

In the sequence, Doctor Strange (Benedict Cumberbatch) and Karl Mordo (Chiwetel Ejiofor) are being chased by the evil Kaecilius (Mads Mikkelsen) and his zealots through New York. They do this, however, in a parallel dimension – the Mirror Dimension – in which space and landscapes become increasingly distorted, unbeknownst to the general public. That means that skyscrapers, roads, and New York surrounds are constantly being folded and warped, ultimately forming a kaleidoscopic array of buildings that are harder to escape from.

Overall visual effects supervisor Stephane Ceretti was charged by director Scott Derrickson with crafting an elaborate chase that, although it made use of extensive visual effects to depict the powers of characters who can harness the mystic arts, was still something audiences could comprehend.

“Even with all those magic powers,” said Ceretti, “we still used elements from the world that are tangible and that the audience could relate to, so that it feels more real in a way. We made sure that the texture of the material that these buildings were made of was really real, even though they behave in a very different manner. At the end of that sequence we go completely crazy, I mean, there’s no more New York, it’s all deconstructed. It’s a gigantic kaleidoscope, but I think people will buy it because we will have taken them from the real New York to the crazy New York in a pace that is okay for them to accept.”

Designing A City That Bends

Understandably, designing the city chase was a huge design challenge, which began with Marvel’s art department, then previs done by The Third Floor, and final visual effects from Industrial Light & Magic. “The spec was to do something no one in cinema had seen before,” said Third Floor previs and postvis supervisor Faraz Hameed. “The designs themselves started with Escher references and from there it was a matter of how to push the boundaries of visual storytelling.”

“A phrase we used a lot was how could we ‘plus it’,” added Hameed. “That meant taking a first pass at an idea, reviewing it, and finding a way to not just to tell the story, but to give you goosebumps when seeing it on the big screen. We really wanted to tease and surprise the audience, which meant trying a usual but still cinematic camera and adding unexpected moves in the transformations that the viewer could still properly follow.”

The Third Floor carried out traditional previs (and postvis) but also detailed techvis for the shots. This involved schematics that provided top, side, and front elevations with camera and distance data. The work helped production decide whether a shot could be achieved with a crane, a motion control rig, whether it would be shot on location or a stage, and even if it was to be filmed upside down or in reverse.

From the previs and techvis, plates were then filmed in both New York and at Longcross Studios in London. The studio work mostly consisted of greenscreen photography with specially designed gimbals and treadmills for running shots. A large amount of wire work and stunts were also required, since the characters would often be leaping between buildings or rapidly moving structures.

A City’s Worth of Shot Ideas

ILM then embarked on its own exploration of the sequence, starting with postvis work from postvis supervisor Landis Fields, who further developed the look of the bending and warping buildings. Some of these additions included specific shots that drew on the Escher reference.

“One idea we had, for example,” said ILM visual effects supervisor Richard Bluff, “was an urban basketball court with players occupying the same space as a building. So what you effectively had was a basketball court sticking out of a building on its side and having the two move in opposite directions. As soon as the basketball court gets to the bounds of the building it would just simply disappear somewhere. It was this idea that the entire city is fractured and you’re just seeing very small elements cut out of the real world.”

During the principal photography in New York, ILM had also installed a team in the city to shoot background plates, LIDAR scans, and photogrammetry elements from several vantage points and locations. Texture references for everything from taxis to building windows were also acquired. This would all then be used in the visual effects process either as real backgrounds or as the basis for cg buildings.

In particular, Fields utilized survey data available for New York along with some early mocked-up shots to plan required helicopter plates – these were filmed with the aid of ILM techvis on an iPad in a heads-up display (HUD) style that the chopper pilot could reference while flying. Fields was also instrumental in crafting an entire ‘virtual background’ of the city, devising a 360-degree camera rig made of GoPros to shoot it with.

“Now it’s pretty easy to get these 360-camera rigs,” said Fields, “but at the time when we first started exploring this there really wasn’t anything out there. So what we did was, we scanned in the GoPros and then we designed a camera rig. We went through multiple iterations and then we 3D printed them, and we did a few fit tests at ILM in San Francisco before going to New York, and we took it out on set. We would put it out on a special rail and hang it say over the ledge of the World Trade Center. This gave us two things; a moving version of a virtual background and a way to visualize the city in 360 degrees, which was done with a vr headset.”

A Warped World

With all that reference and real photography, ILM began building the city in cg. They quickly found that with all the movement and bending and warping that 3D assets had to be as high-res as possible, including even the cars and crowds in the scenes, and occasionally digital doubles of the actors. The result was that, even though ILM had reference and aerial photography, they needed to up-res it significantly. “What we found was that the amount of detail we had to put into those textures to replicate what you actually perceive from aerial photography was huge,” said Bluff. “We needed four or five or six times the level of detail that you think you’re getting out of your 6K plate on those buildings to make sure that you believe the image that you’re actually seeing.”

To get their cg buildings absolutely correct, especially for wide shots and one major ’sinkhole’ section, ILM looked to survey data of New York. “From that data,” said Bluff, “we were able to map the terrain of the underlying ground the buildings sat on and then we could then extrude the right heights of the buildings. We used readily available top-down photographic imagery to understand the bounds of those buildings, but by the end of that exercise we believe we have the most accurate version of New York that exists for re-use on aerial photography. So once we had that geometry it was relatively straightforward to snap it to the footage that we had to project the plate and start to deform the buildings.”

Building the city in cg was tricky enough, but making the surreal city warps was even harder, especially when things like street signs and smaller building pieces became more kaleidoscopic in nature. It was here that fractal and ‘Mandlebrotting’ elements came into play, as well as seemingly random moments of action.

“There’ll be a moment where the street is seemingly sliced off, but a car happens to move across that slice,” said Bluff. “So a car happens to just erode away as it moves and disappears, in theory reappearing somewhere else in the city. The idea of being able to play with those sorts of ideas was very unique, and challenged the artists and gave them a huge sense of ownership over what we could do.”

One particularly challenging shot involved the characters falling through a subway car and transitioning through five different environments in a single camera move, designed to show the chaotic environment that this Mirror Dimension version of New York had become.

“We started by forming this long tube that Doctor Strange is sliding down, but we also wanted to introduce a lot of jeopardy and show that there’s some passengers in the train and they’re unaware that it’s happening because it’s in another dimension,” said Fields. “We actually did a photo shoot here at ILM just for that specific shot where we went and got 44 people from production and marketing [departments] and did photogrammetry where we would shoot 360-degree photos around each individual person and then we reconstructed that geometry to have as background photo real digi-doubles that we could just rapidly generate.”

That tube shot perhaps epitomises the overall approach to the whole sequence. While certainly a huge amount of computer generated imagery was involved, it also began from actual photography, as Ceretti noted. “That’s the idea behind everything in the film – trying to shoot stuff that is real and then push it and distort it and make it something different, but at least you start from the real thing.”