How Studio Ponoc Pushed Innovation In 2D Animation With Its Latest Feature ‘The Imaginary’

The pipeline for traditional, hand-drawn animation remains a methodical process, which is why it’s taken six years for Studio Ponoc’s second animated feature, The Imaginary, debuting tomorrow, July 5, on Netflix.

While the film was released last December in Japan, The Imaginary is the first title in the deal which gives Netflix the global streaming rights to Studio Ponoc’s animated features. This film is based on the 2014 children’s book of the same name by A.F. Harrold, with the screenplay adapted by Studio Ponoc founder and the film’s producer, Yoshiaki Nishimura.

As the head of Studio Ponoc for almost a decade, Nishimura says choosing The Imaginary for their follow-up feature afforded them the opportunity to move outside of their storytelling comfort zone, push the look of their animation, and most importantly, give legendary Studio Ghibli animator Yoshiyuki Momose another feature film to direct.

“When I entered Studio Ghibli, of course Miyazaki and Takahata were the big names, but there was the third man of Mr. Yoshiyuki Momose who was a special presence in Studio Ghibli,” Nishimura told to Cartoon Brew. “Unfortunately, he wasn’t able to direct a feature film at Studio Ghibli. So I had promised myself that when I get to the position of being able to select a director for a feature film, I would really like to have him direct a film.”

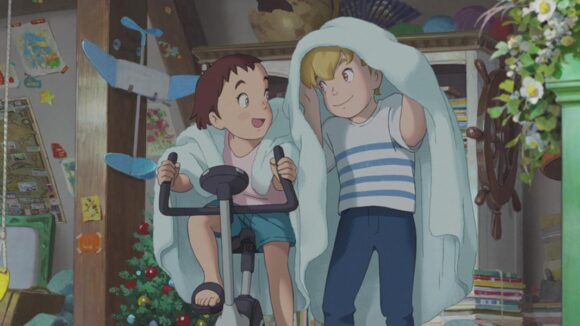

Harrold’s book about a young, troubled British girl named Amanda, and her imaginary friend, Rudger, immediately struck Nishimura as a story that would lend itself to Momose’s skills in imparting emotional storytelling and crafting ambitious world-building.

“I realized that it was a world that was derived from children’s imaginations,” Nishimura said. “But each child’s imagination is different so we couldn’t depict it with a single type of look. When we got the agreement to be able to [produce] this, I thought that [Momose] would be the best person to direct this film.”

Nishimura said he was also excited by the premise of the book being so different from Japanese culture. Where Western children embrace and understand the imaginary friend concept, Japanese children instead gravitate towards spirits, ghosts, and yōkai as seen in many Studio Ghibli films.

In order to best sell the “odd” premise to the Studio Ponoc production team, Nishimura said he wrote an exhaustive 40-page treatment of the adaptation which he presented to Momose. It was so detailed that Momose suggested that he be the one to write the full screenplay and they could continue developing it together.

Storywise, the duo dove into building out emotional stories driving the actions of Amanda, Rudger, and Emily, who is the experienced leader of the town of imaginaries. Nishimura said they put a lot of thought into the origins of imagination for children, and how their experiences with the world around them and the books they’ve read help shape their interior spaces.

“We asked, what is Amanda’s life like? And what does the bookstore mean to her? And in terms of her mother, Lizzie, and her father, what is the situation there?” said Nishimura. “In the original story, there is only one line in the book about the father, that he’s not there. When I thought about the character of Rudger, I thought it must be related to her understanding of who her father was. So in terms of the design and the reason for that imagination, it is because of the father, or the lack of the father. So that’s how I develop the script and then the characters as well.”

As for the animation itself, Nishimura said he and Momose were both more than ready to make a film with techniques that would elevate beyond what they’ve all done before.

“We did have some dissatisfaction,” Nishimura admitted about the status quo mentality amongst some in the 2d Japanese animation industry. “Even when we had done Mary and the Witch’s Flower, I was thinking, ‘Am I going to continue this for 30 years? I’m going to get bored.’”

For the studio’s anthology film Modest Heroes, Nishimura’s team dabbled with new approaches to lighting and shading 2d animation. The Imaginary was an opportunity to challenge themselves even further, which led to a collaboration with the French company Les Films Du Poisson Rouge that had helped to develop the lighting techniques for Sergio Pablos’ Klaus.

“It wasn’t that I wanted to show the figures in a more 3d type of way,” Nishimura explained. “I felt that if we could control or work with shadow and lighting more, then we could show more psychological and deeper aspects of the characters to the audience. Dealing with the light and shadow would deepen the story, deepen the feeling that the audience got, and that’s what Les Films Du Poisson Rouge group had.”

Deep into production, Nishimura contacted Poisson Rouge to have their artists apply a final pass of augmented shading and lighting which was overseen by the studio’s lighting director Anaël Seghezzi and producer Catherine Estévez. Said Nishimura, “We had completed the entire footage in the Japanese version and then we sent it to Poisson Rouge where their lighting director worked on the lighting and shadow for what we did.”

Nishimura said they also identified in the storyboarding stage that they wanted to augment a few key sequences with cg elements. He detailed the process of how such decisions are made at Ponoc:

The storyboard is usually divided into four parts of 25 minutes each. When each part gets completed, then the main staff meets and we decide how to handle the drawing of it, and whether it should be hand-drawn and painted. Or, should we focus on the background art or what kind of cg to put in. I think we could say maybe 10 to 15% in the film. Specifically in the outer space sequence and then the origami bird sequence too. But we have a policy on using cg. Many Japanese animators like to use cg simplify things and to make it easier. But our policy is [to ask] will it help in terms of the expression of the film? That’s what we focus on.

While those sequences were produced by outside vendors, Nishimura said they’ve been internally discussing whether they should expand Studio Ponoc to include in-house cg capabilities. “Right now, we basically outsource it because those companies have a much faster rate of developing new methods of cg and then using them, so we’ve outsourced it.”

With The Imaginary having been well received in Japan and with strong anticipation for its global release , Nishimura said he’s even more determined to continue to honor the tradition of 2d animation, while finding ways to push the art form forward. “In Japanese hand-drawn, hand-painted animation there’s a limit, so that’s why we tried to bring in the shadow aspect. I think we are pushing those borders and we’re trying to push through the borders at Studio Ponoc, too.”