How Laika Pushed 3D Printing to New Heights with ‘The Boxtrolls’

Today at SIGGRAPH 2014, Laika is presenting a session about the making of their upcoming stop motion feature The Boxtrolls and among the presenters is Brian McLean, the studio’s Director of Rapid Prototyping. During a recent trip to Laika’s Portland, Oregon-based studio to visit the set of Boxtrolls, Cartoon Brew chatted extensively with McLean (pictured below) about the revolutionary introduction of the 3D printer into the stop motion production pipeline.

“We became the first company to take the age-old technique of replacement animation and combine it with the 21st century technology of 3D printing,” McLean says.

“We became the first company to take the age-old technique of replacement animation and combine it with the 21st century technology of 3D printing,” McLean says.

If you’re not familiar with the term “replacement animation,” it is a technique used in stop motion in which parts of a puppet, usually faces or limbs, are replaced with similar (but ever so slightly different) parts to achieve the illusion of movement. McLean’s department is responsible for creating the replacement faces used during production. “On Coraline we produced upwards of 20,000 faces, ParaNorman was around 33,000, and with Boxtrolls we’re upwards of 52,000,” he says.

The faces, which resemble mini-Noh masks, are generally broken up into two broad parts—eyebrows and mouth–and placed into “facial kits.” The kits are grouped into expressions like “up surprised eyebrows” and “frown mouths.” If you were to mix the same “up surprised” eyebrow with a “smile mouth,” you’d get a different facial expression than you would with a “frown mouth.” Put simply, the more replacement parts, the broader the performance possibilities for the puppet.

While Coraline had a potential 200,000 facial expressions, Norman from ParaNorman had an estimated 1.4 million. Eggs, the star of The Boxtrolls, clocks in with about the same amount of expressions, but he has a higher level of performance than his predecessor. “We’re getting so much more tension and musculature and volume change,” McLean explains. “We’re animating almost every square millimeter of Eggs’ face, whereas with Norman we essentially had the mouth moving and some cheek movement.”

McLean isn’t satisfied with simply a bigger facial library, and believes that the goal of his rapid prototyping department is to try and “push stop motion performance into uncharted territories.” To that extent, for Boxtrolls scenes where the animators needed a one-of-a-kind performance, faces were designed specifically for those individual shots, printed out, and used just once in the production. “We dabbled a bit with [single-use puppets] for ParaNorman and there’s a couple of key acting moments with Norman that we used it with, but we really opened up the flood gates with The Boxtrolls,” says McLean.

McLean shows us a scene of a character slamming his fist on a table; the reverb from the reaction is reflected in their face. There’s a sense of weight and bounce that moves through the facial replacements that feels more like flesh than what it actually is, which is hard pieces of plastic magnetically snapped to a puppet’s head.

“There’s a couple of reasons why you do specialty performance,” says McLean. “One is because you want a lot of subtlety, you want some follow-through or something unique in the performance that wouldn’t be evident in the kits, and then the other is you really want to push the performance with some really grandiose expressions beyond what a kit could possibly do.”

As 3D printing technologies advance, the Laika artists are able to achieve more vibrant and accurate colors in their printed models. They were excited to get rosy cheeks on Norman because Coraline couldn’t have rosy cheeks. Today they are achieving more sophisticated effects than even the manufacturers of the printers thought were possible. “Often times [they are] coming back to us and saying, ‘How the hell are you guys doing that?’” McLean says.

He credits the film’s lead texture artist, Tory Bryant, for figuring out how to recreate the subtleties of the hand-painted maquettes through the 3D printing process, something that didn’t seem possible just a few years ago. Bryant not only invested great amounts of time into figuring out how to compensate for the lack of color calibration on the printer (the solution was a surprisingly old-school method using color chips in a Pantone book), she also discovered that applying traditional drawing and painting techniques onto the digital models resulted in more textural effects. Bryant’s digital texturing of the character’s faces use a cross-hatching technique, McLean says, and “what that meant was when it was sent to the printer, the printer builds up in layers.” The resulting printed paint job has an ever-so-slight translucent quality that feels more like human skin.

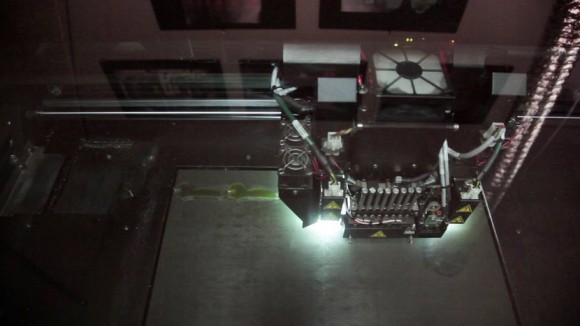

With five color printers on site, Laika can print 100 to 150 mouths in a day for a character like Eggs, whose head is relatively small, however larger characters pose a greater printing challenge. For example, there is a character in The Boxtrolls whose face is so large they could only produce 12 a day.

The process of the rapid prototyping department is complex. It begins with scanning a hand-sculpted maquette head into 3D, and then refining it with digital software—Maya mostly, and ZBrush sometimes. This modeling process is especially important because 3D printers tend to soften out edges and details. The digital models have to be purposefully exaggerated to retain their sculptural origins and compensate for the printing output.

After modeling, the process becomes much like a traditional CG workflow, and moves through rigging, texture painting, and animating. But instead of rendering out the final images as frames, they are sent to a 3D printer. It’s not as simple as printing out a single face though. Each character’s face is made up of dozens of components: a few that the audience sees like the face, the eyes, and the mustaches, and a variety of internal pieces that enable the animator to bring a character to life onscreen. Many of those internal parts also have to be designed, modeled, and printed in the rapid prototyping department.

Fifty people work in Laika’s rapid prototyping department: half of them create the CG assets, while the other half are responsible for processing these parts as they come off the printers. “[The processors] are the unsung heroes,” McLean says. “Everyone assumes the printers produce these wonderful pieces [that] are perfect when they come out, but they’re not. They often times are a mess.” This team of 25 people has developed a post-processing system to help maintain consistency between the pieces, which sometimes includes sanding down edges, smoothing out inconsistences, and applying pastels directly to the piece by hand. “We are [using] a technology that was never designed for replacement animation, never designed for mass production at this level of scrutiny and this level of precision between parts.”

We asked McLean what’s next for 3D printing in animation. “3D printing is really in its infancy right now. When we started doing it on Coraline, not many people had any idea what a 3D printer was—now it’s sort of the buzzword. I would love to see new material compositions come out that are better for color, and getting a better resolution with more refined printing. I want to be able talk to you three years from now and not have there be any limitation between the subtlety that we can put into a face and our ability to get the most of out of a character.”

The Boxtrolls will be released in the U.S. on September 26, 2014.