Gints Zilbalodis On The Improvisational Filmmaking Style Of ‘Flow’

At a slender 85-minute running time, the Janus Films/Sideshow release Flow is a small miracle of a film. The second feature from Latvian animator Gints Zilbalodis, following his solo-created debut Away – winner of Annecy Film Festival’s 2019 Contrechamp Award – Flow was by design a more collaborative exercise.

Created primarily in Blender, with a stylized all-animal cast, Flow is a wordless drama set in a dreamlike, post-apocalyptic era. Jungle settings are eerily devoid of humans and, from time to time, succumb to terrifying floods. Protagonists include a small housecat, a boisterous Labrador, an amiable capybara, an acquisitive lemur, and an errant secretary bird, all of whom band together in a struggle for survival.

The project was produced at Dream Well Studio in Latvia, with 3d character animation created in France and Belgium, as an outgrowth of a short film. “I first started doing animation when I was eight,” Gints Zilbalodis, 30, told Cartoon Brew. “I had Flash software that I used to make silly internet cartoons, and then, when I was 15, I became more serious about it. That’s when I made my first short film, Rush. I was interested in any type of filmmaking, but I felt like I had more control over things that I could animate over time, and I could tell fantastical stories. After Rush, I made my next film, Aqua, which was like the early version of Flow.”

Aqua’s images of a small cat in a swirling ocean, which Zilbalodis created while studying painting and drawing at Janis Rozentāls Art School, in Riga, offered hints at Flow’s themes. Zilbalodis gravitated toward 3d animation, which he expanded upon in Away. Away’s success on the festival circuit paved the way for Flow.

Cartoon Brew caught up last week with Zilbalodis, who was on a press tour in New York City, to discuss his new film. Since the interview, Flow went on to win the New York Film Critics Circle award for best animated feature of 2024.

Cartoon Brew: Take us through your creative process on Flow. Did you and your co-writer Matiss Kaža start with a traditional screenplay?

Gints Zilbalodis: In my previous films, I just had an outline. In this case, we had a bigger budget, and to get the funding, we needed a script. We wrote many drafts, and it kept evolving. After finishing the script, I did not read it again. Even when I was making the animatic, that was based on my memory of the script. I made the animatic chronologically. I created the environment, then I explored it with the camera. I like the freedom of exploring the space with the camera. And this was necessary because the camera moves so much. It was impossible to draw that.

The film is full of imagery of flowing water, but the camera also flows through this landscape. How did you do that?

That happened in the animatic process. I move the camera and the character simultaneously. It’s like a choreographed dance between them and it’s a very spontaneous, organic process. I tried using an app on my phone that allows you to record like a camera as you walk around, but I found that to be imprecise.

Instead, I keyframed the camera. I’d place it in the first position, and then add the next. I then added layers of handheld movement. I had multiple types of movements, for standing still, walking, and running. That gave me control, and I could add imperfections, which helped the tension of the film. It also made it feel more grounded as if the camera was not catching everything perfectly, like a real person trying to react to events. I wanted it to feel like we were inside this world, not observing from a distance. I went through that process chronologically, which allowed me to think about transitions between the shots. That took a year and a half. I was doing other things at the same time, setting up our studio, hiring people, and creating the workflow.

The opening is a great setup, revealing the cat’s home abandoned but surrounded by strange feline sculptures. How did you build that?

That’s a good example of how ideas were discovered during the animatic process. In the script, we didn’t have the cat statues. There was just a single statue of a human figure. During the animatic, I decided to add more statues and make them cats, instead of humans. But then I took that human statue and I put it in a later scene. The reason why I changed the statues into cats was that I needed to show time passing when the water rises, flooding the home. And I thought the image of the cat statues drowning created a sense of anxiety for the cat.

I then had to reverse-engineer the logic of why the statues were there. We knew this was a house that the cat lived in, but after adding the statues, we changed it to an artist’s workshop. Maybe this was the owner of the cat, and the cat was this artist’s muse?

Tell us how you got into the animals’ heads, especially that curious, frightened, little feline – is he, or she a kitten?

We didn’t consider the age or gender of the animals. Hopefully, you can see your own pet in them. We animated all the animals by hand. Of course, we couldn’t put cats in motion capture suits and drop them into water. Also, cats don’t do what you ask them to do. We did look at a lot of references. We studied our own pets, and videos on Youtube, and we went to the zoo. I would describe our approach as naturalism rather than realism. The difference is that we were studying real life, not copying it. We were observing and telling a story.

As we get to know the animals, they do slightly magical things, like using the tiller of a boat to steer their way down a river. How did you gauge those moments?

It was important that these characters have agency. We started very grounded and gradually went to more of a magical realism approach later. It happens gradually, and we have some setups, so it doesn’t happen out of thin air. But even in these moments, we looked for animal behaviors that we could use.

The animals are unnamed in the film, but there are photos of a Labrador retriever on your Instagram that resemble the dog in the film – what is his name, and how did he inform that Chaplin-esque canine?

I have two dogs, Audrey and Taira. I think, even though the dog is a funny character, we didn’t sprinkle jokes on top of the story. Its behavior is driven by its character. The dog is the opposite of the cat. The cat ends up learning to trust others, but the dog starts at that place and ends up more independent. I wanted to show that there are positives and negatives to both of those ideas.

There is geographical mix among the animals – lemurs are native to Madagascar, capybaras are from South America, and secretary birds are from Africa. Were they mixed up by this flood?

I wanted a variety of animals, and I wanted them to be visually distinctive, but I didn’t think about the logic too much. Maybe there was a zoo that they all escaped? Or, maybe they were movie-set animals and they were shooting a film somewhere?

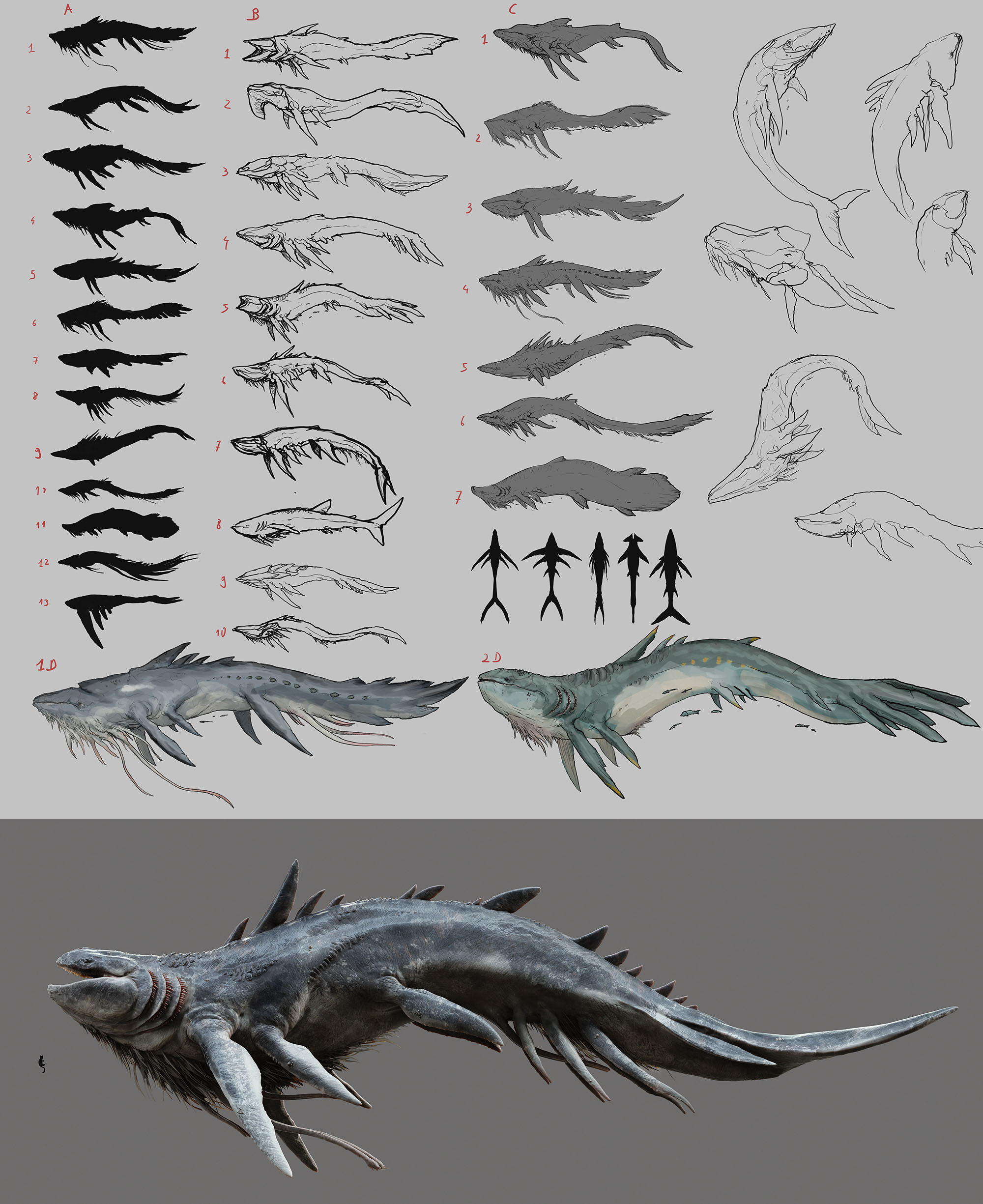

One of the most mysterious creatures is a whale-like cetacean who feels like he has a deeper, mythical feeling. What were your concepts for that?

During development, it was a whale, but it needed to represent the cat’s anxieties and fears of the unknown. We as humans know that whales are peaceful, and I wanted to put the audience in the cat’s perspective and make it afraid of the whale, so we changed the design to make it more of a mythical creature. It feels scary, but later – I don’t want to spoil it – the cat overcomes those fears.

How did you design your natural environments?

A large part of the story takes place on a boat, and we didn’t want that to feel claustrophobic. They visit a variety of places, with different moods. And through the environments, we get an understanding of what happens within the character’s heads. We wanted it to feel timeless. There are no modern-day buildings. And we combined different influences, to create a sense of adventure.

They travel toward a mysterious sunken city, which takes on great significance for the cat in its friendship with the bird. What were your concepts there?

The city was meant to evoke a maze and an obstacle. The cat feels helpless on its own, but with the bird, it manages to overcome those challenges. That environment needed to be imposing, but I didn’t want it to feel like any real place. They are not canals that they are navigating, they are flooded streets, where we see trees submerged with fish swimming through. Even though it feels post-apocalyptic, I wanted it to feel like this was maybe a new beginning. Nature is reclaiming these places.

There is a cosmic element with what looks like aurora borealis beckoning the cat, leading to a moment of epiphany. How did you design those visuals?

I knew the characters should have a goal, and the cat, who is always trying to climb up high to escape from the flood, becomes obsessed with reaching these distant towers. So, I knew that they were going there, but I couldn’t figure out what would happen once they reached this place. As we wrote the script, I also wrote the music, and that unlocked ideas. I used some electronic instruments that evoked this cosmic imagery. That guided the scene. I wanted it to have enough time to develop. There was a pretty extended climbing [sequence] that I wanted to create a sense of an arduous journey. And when they reach their goal, there is a big climax. We created these abstract, surreal sequences to understand what the characters are feeling, and that is conveyed in a very expressionistic way.

You’ve spoken about what Flow represented for you in finding your way as a team leader. To give your team a shout-out – how many worked on this?

We did preproduction, modeling, texturing, music, and color grading, all in Latvia. But in Latvia, we have traditions of hand-drawn and stop-motion animation, but we don’t have many cg animators. So in France and Belgium, we did character animation, particularly in France where there is a huge industry. We worked together, which fitted well with the theme of the film. We had about 20 character animators. Animation took about half a year. The whole production was five years. In Latvia, we were a very small team, me and two or three other people. We all fit in a single room. Some worked on the film for a week or two, others worked for a year. Altogether, we had about 45 people.

What’s next for you?

I am going to try to maintain this independence. On a smaller budget, we have more freedom to tell personal stories, to explore techniques, and take bigger swings. It is exciting that films can be made in places without a big industry, with different perspectives and different types of stories. And, because it’s animation, it can reach a global audience. We’re not bound by any specific culture.